RV Capital commentary for the second quarter ended July 30, 2021.

Q2 2021 hedge fund letters, conferences and more

Dear Co-Investors,

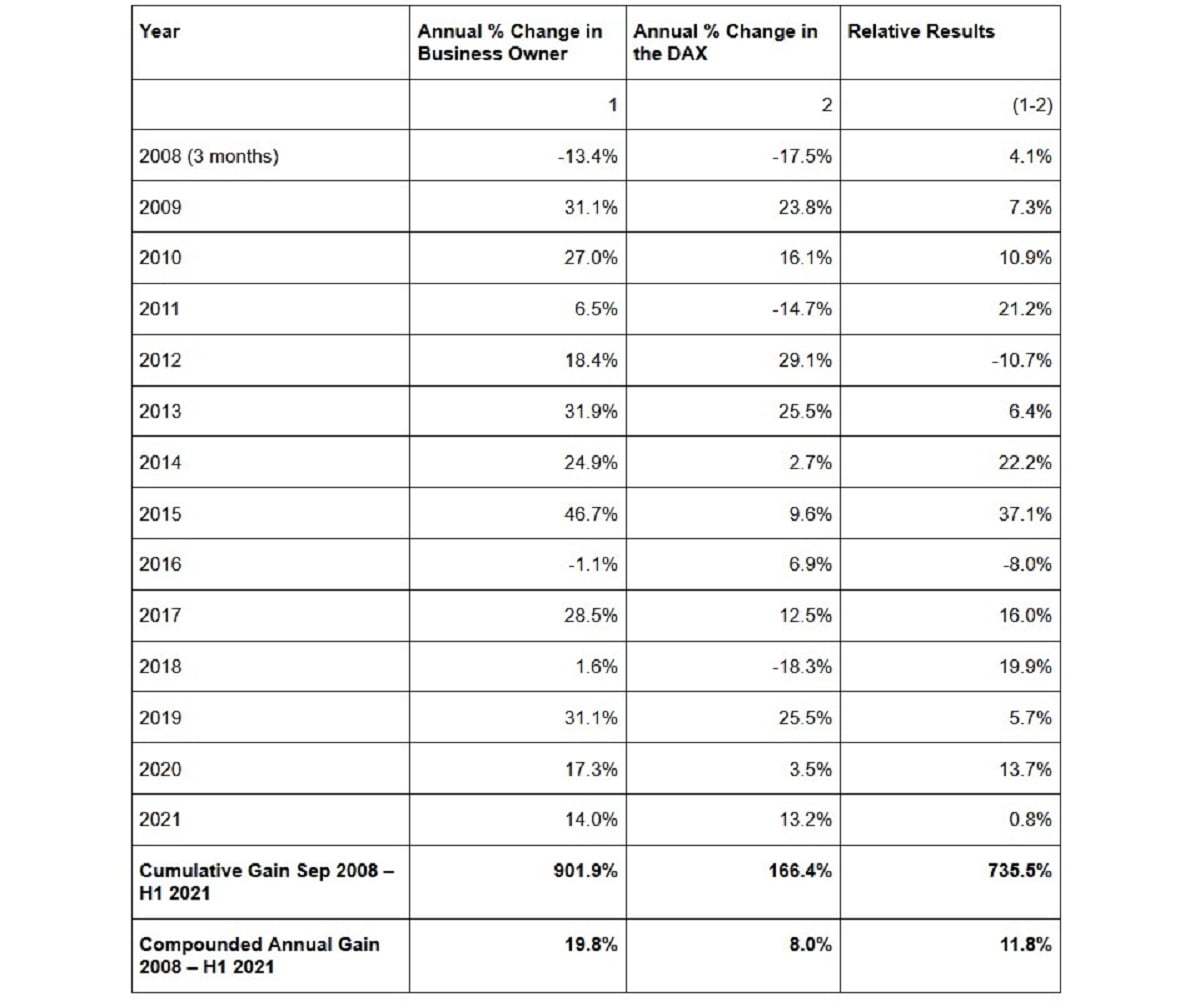

The NAV of the Business Owner Fund was €994.14 as of 30 June 2021. The NAV increased 14.0% since the start of the year and 901.9% since inception on 30 September 2008. The compound annual growth rate since inception is 19.8%.

Part 1: Humility

It continually takes my breath away how differently things can turn out compared to what might reasonably be expected at the time. It is what makes investing endlessly fascinating but also incredibly hard. I was reminded of this recently by Credit Acceptance’s second quarter results. Collections for its 2019 cohort of consumer loans – the last one before the Covid-19 crisis – are not only tracking ahead of its initial expectations but are showing a large, positive variance.

If I teleport myself back to March 2020 when the global economy was at an almost complete standstill, the only question on my mind was how bad unemployment could get. Did the Great Financial Crisis constitute a worst-case scenario? Or the Great Depression? Or neither? The idea that the 2019 cohort would not only do better than expected but by a large margin would have been laughable. With hindsight, it is easy to rationalize it, now that we know about stimulus cheques and the impact of the semiconductor shortage on used car prices. However, neither of these developments were known nor knowable at the time. It is a reminder, as if one were needed, of the importance of humility.

Part 2: Increasing our Investment in China

The most consequential capital allocation decision in the first half-year was to increase our investment China by purchasing a new position in Alibaba and increasing our holding in Prosus, the major shareholder of Tencent, China’s largest internet company. I expect more investments to follow.

I wrote about China in my 2019 half-year letter but given the heightened pessimism in the West today around China, I thought it was worth updating you on my thinking before getting to the discussion of our new investment in Alibaba.

I am conscious that the segue from a discussion on humility to one on China may be jarring. There are, for sure, many people better placed than me to discuss China. I hope, though, that there is value in the perspective of an informed outsider who has invested through several market panics in the past.

What Just Happened?

Over recent months, there has been a growing sense of pessimism bordering on panic about China and its internet companies. From peak in February to trough, aggregate paper losses of the largest Chinese Internet stocks have exceeded US$ 1 trillion.

The roots of the panic can be traced back to last November. Jack Ma, Alibaba’s iconic founder and major shareholder in Ant Group, gave a speech which was critical of financial regulation in China. Shortly afterwards, Ant Group withdrew its IPO plan, giving rise to fears that the Chinese government was turning its back on the market economy. Since then, regulation has spread to other sectors and increased in both frequency and intensity, heightening these fears.

What Do I Make of It?

At a high level, my sense is that investors in the West are missing the wood for the trees. They focus primarily on what is perceived to be going wrong in China (in this case regulation) as opposed to all that is going right. Yes, regulation is increasing in China, but where is it not? It may or may not be a net positive for investors, as I discuss later, but irrespective of this, the important point to grasp is that the direction of the economy and living standards is firmly up and to the right. The debate around regulation is a distraction.

Oddly enough, this pessimism has not stopped people increasingly viewing China as a strategic competitor. I think you can take the view that China is a strategic competitor, or you can take the view that the economy is a train wreck waiting to happen, but you cannot hold both views.

I can only speculate what the reason for this excessive pessimism is but suspect it is primarily a function of the way media works in general. The news tends to focus on rare and sensational events as opposed to small, incremental improvements. A tycoon being dressed down gets more airplay than a new hospital being opened.

I also suspect that cognitive dissonance, i.e., the difficulty of keeping two contradictory thoughts in mind at once, is at play. There is considerable antipathy in the West to a political system that is based on single party rule. This leads people to either downplay or ignore the achievements of said system. To my mind, it is possible to disagree with the system and acknowledge its achievements. In fact, to make a coherent argument against the system, you must account for its achievements.

What about Regulation?

Without wishing to take anything away from my prior point that regulation is garnering more attention than it likely deserves, I want to turn now to said regulation.

What follows is an overview of some of the key regulatory initiatives. It is obviously a simplified and incomplete summary of a complex and wide-ranging topic. I hope though that it gives the non-expert a sense of what regulators’ priorities are and what actions they have taken. If you want to dive deeper into the topic, I recommend Rui Ma’s excellent blog Techbuzz China, which was an invaluable resource in preparing this section.

“Two Choose One”

A big focus of regulation has been the removal of exclusivity provisions known as “Two Choose One” whereby dominant online platforms banned suppliers from working with competitors. This primarily impacted Alibaba in e-commerce and Meituan in local services. It is part of greater antitrust actions, which include banning anticompetitive practices such as discriminatory pricing and bundling. In addition, there is more on opening up walled gardens, which primarily impacts Tencent. Tencent Music, China’s leading music streaming company, was ordered to remove exclusive rights to music catalogues.

The Gig Economy

Conditions for temporary workers is a further area of regulation. Local services platforms will have to make social insurance contributions for drivers. In addition, there is a focus on the unintended consequences of algorithms, safety, working hours, accident insurance and minimum pay levels.

Financial Stability

Financial stability is a big priority. Ant Group was ordered to restructure as a financial holding company and will be regulated by the Central Bank. Amongst other measures, it was ordered to retain more of its loans and hold minimum levels of capital against them. The same rules were later applied to all market participants.

After School Tutoring

After School Tutoring companies were ordered to curtail most of their activities in the compulsory education sector and convert to not-for-profit organisations.

Online Gaming

The Economic Information Daily, a state-owned paper, published an op-ed describing video games as “spiritual opium” though this reference was later redacted. Further restrictions are likely around the amount of time school-aged children can spend gaming.

Data Privacy

Data privacy is a hot topic in China as elsewhere. China recently passed the Personal Information Protection Law (PIPL) - often referred to as China's GDPR.

Common Prosperity

Growing income disparity is a concern in China. Common prosperity is a goal of the Party whereby there have been no specific policy actions as far as I am aware. It did however mention “three distributions” referring to the three sources of wealth – markets, government and Society, i.e., philanthropy. Sensing how the wind is blowing, Tencent has announced two funds of RMB 50 bn each for a “common prosperity program”.

Fines

Alibaba received the largest fine to date totalling $2.8 bn or roughly 0.5% of its then market value for anti-competitive behaviour. At the other end of the spectrum, some of the fines have been miniscule. Tencent and Alibaba were fined $77’000 (no zeroes missing) for misreporting some acquisitions.

Key Takeaways

What are my key takeaways?

-

Concerns of regulators in China are no different to regulators elsewhere

They include platform power, employment conditions of gig workers, time well spent, income inequality, and so on. It is a reminder that for all the differences between China and the West, what unites us is far greater than what divides us. The approach to solving the problems thrown up by the internet may differ (see next point), but the fundamental realisation that the world has changed, and existing laws and regulations are no longer fit-for-purpose is shared.

-

The biggest difference between China and the West is in approach

Having identified a problem, regulators in China can swiftly act. In the West by contrast, attempts at regulation typically take years to work their way through the political and judicial system if indeed they can work their way through at all. This of course goes to the heart of the difference between the two blocs’ political systems – one based on absolute control at the centre; the other with distributed control tempered by both political and judicial checks and balances.

I prefer the way things work in the West for all its drawbacks, however it is important to acknowledge that there are trade-offs. In the West, it is harder for government to get stuff done (including the good stuff). In China, it is easier for government to get stuff done (including the bad stuff). In the area of regulation specifically, my best guess is that a bias for action is likely a net positive for Society given how inadequate existing laws are. As such, regulation makes for a poor bear argument against the Chinese economy in aggregate.

For individual companies, the situation is more nuanced. For example, in the case of local services companies, better working conditions for gig workers may raise their costs in the short run but make their business more sustainable in the long run by better aligning the interests of all stakeholders and creating a level playing field for all competitors.

-

The financial impact of regulation varies by industry

In most cases, the financial impact seems to be at worst manageable and at best inconsequential. For example, the removal of exclusivity provisions is no doubt a net negative for dominant platforms (and accordingly a net positive for smaller players). However, they derive their market power from other sources (most importantly aggregating huge demand). As such, I am sceptical the impact will be that great. Amazon seems to be doing fine in the West without “Two Choose One”. A similar argument can be made about online gaming restrictions for minors. Tencent has stated that under-16s make up just 3.2% of its domestic gaming revenue.

The one sector where the impact of regulation has been catastrophic for shareholders has been after school tutoring. However, I believe the circumstances are unique to this sector. It is widely viewed in China as toxic for ruining childhoods and placing undue financial strain on parents. The key takeaway is that if a company is a net negative on society, it can expect to find itself in the crosshairs of regulators. As per my previous point, this is likely a net positive for the economy overall though not for all individual companies.

-

Intended regulatory outcomes seem sensible and desirable

They include, for example, better protection for gig workers, financial stability, and fairer competition. There is of course no guarantee that these goals are achieved – unintended consequences are rife with regulation. However, the intent, in my view, matters given the apparent consensus in the West that the goal of regulation is to turn the clock back on capitalism. The intent is clearly to strengthen the market economy, not dismantle it. In the words of the Chinese government, the aim is stable, high-quality growth, not just fast growth.

-

Proposed regulation is not dissimilar to the status quo in the West

This too is inconsistent with the idea that “China is turning its back on capitalism”. Moreover, it suggests an explanation for the pace and breadth of new regulation now: China simply had a lot of catching up to do. This certainly is confirmed by my own subjective experience. I was amazed how often mergers were announced with the stated goal of eliminating competition (for example in the ride share, food delivery, and online travel sectors). This would never have been permitted in the West. An alternative explanation for the sudden burst of regulation now is that China prefers to let markets develop first and only regulate once they reach a level of maturity, and it is clearer what needs to be done. This is certainly something European regulators could learn from. No doubt, it also plays a role that the end of President Xi’s ten-year term is approaching, and there is political jostling.

-

Regulation has been principle-based and evenly applied

It has not been arbitrary or targeted at specific market participants. This contradicts the initial consensus amongst the Western media that the goal of regulation was to settle scores with tycoons who had fallen out of favour with Beijing. Alibaba illustrates this point well. Whilst the outlawing of “Two Choose One” was likely a negative for its e-commerce business, where it is the market leader, it is potentially a positive for its local services business, where it is a clear number two behind Meituan. Furthermore, Tencent has found itself in the crosshairs of regulation despite going out of its way to keep the government on side. Clearly, the goal of regulation is to create a more level playing field.

-

The Chinese government is not looking to destroy its internet champions

The fines meted out so far are small relative both to levels in the West as well as the size of the companies impacted. The impact of regulation seems manageable except for after-school tutoring, which, as I argued, is a special case. To the contrary, I am sure the Chinese government is delighted that the dominant Internet companies are Chinese owned and run. The alternative – an internet dominated by American behemoths – is surely less palatable.

Conclusion

Regulation is clearly increasing in China (again, where is it not?). This seems to be as much a function of the lack of regulation in the past as a desire to over-regulate today. Overall, the changes to date seem manageable except for companies that are viewed as a having no societal benefit, who can expect little mercy from regulators. The pace of regulation is certainly faster than the West, reflecting the different political system in China. The priorities though seem similar.

Ultimately, it will be fascinating to see which model wins through, whereby it is not a zero-sum game, and there is no reason why both cannot be successful (or unsuccessful for that matter). Overall, it is not clear to me that one approach to regulation is unambiguously worse than the other. As such, the conclusion that many seem to be drawing in the West – that China is un-investable - strikes me as wrongheaded. I, for one, will not be deterred from investing further in China.

Part 3: Markets Are Not Always Rational

So far, I have advanced rational arguments why I believe capital markets are overreacting to the perceived change in regulatory risk in China. In my experience though, short term moves in share prices have a tenuous link to rational arguments, if any at all. I first experienced this in the dot com boom in the late 1990s. In the frothy market of the time, almost any press release by a company was rewarded by a jump in its share price. As a result, companies simply started putting out more press releases, irrespective of how inconsequential the news was. People presumably understood that the jumps in share price made absolutely no sense, but they did not care – they were betting on how they thought everyone else was going to react.

I see a similar dynamic in China today albeit in reverse – almost any regulatory utterance is greeted with a sharp share price decline at the affected company, irrespective of how consequential it is to its business.

After the dotcom crash, it was cash flow, not news flow, that ultimately drove companies’ market values. I have no doubt the same will be the case here.

Part 4: A New Investment in Alibaba

In the first half of 2021, we became shareholders in Alibaba, making it our second investment in China after Prosus.

I have admired Alibaba for many years and visited it for the first time on a trip to Beijing in 2013. I recall that the previous occupants of the meeting room had left an aspirational figure of USD 1 Trillion in Gross Merchandise Value (“GMV”) up on the white board. At the time, we all had a good laugh at the absurdity of the target. Fast forward to today, nobody is laughing. Admittedly, this likely has more to do with the precipitous decline in the share price than the recognition that the value of goods transacted on its platform has surpassed the astonishing sum of US$1 Trillion.

Alibaba is, of course, one of the largest and best-known companies in the world. For this reason, I will briefly summarise the investment case to allow more time for a discussion of where my view on the company differs from the (more pessimistic) consensus.

Who is Alibaba?

Alibaba is the second largest internet company in China behind Tencent with a market value just shy of US$ 500 bn. It was started in Hangzhou in 1999 by Jack Ma, a former English teacher who had discovered the internet during a business trip to the US.

Alibaba operates two of the most popular e-commerce sites in China: Taobao, which connects private sellers and smaller merchants with consumers (“C2C”); and TMALL, which connects larger merchants and brands with consumers (“B2C”). As of 31 March 2021, it had 811 m annual active customers on its China retail marketplaces and a GMV of RMB 7.5 Trillion or US$ 1.1 Trillion.

The marketplaces main source of revenue is from customer management. Customer management revenue primarily comes from advertising (mainly pay-for-performance) and commissions (mainly a take-rate on GMV). Total customer management revenue in FY2021 was RMB 306 bn or US$ 47 bn, which is 4% of GMV. Its marketplace-based core commerce adjusted EBITA was RMB 229 bn or US$ 35 bn.

In addition, Alibaba has several other businesses. These include a 30% stake in Ant Group, a financial services company which started in online payments but branched out into consumer and small business lending, insurance, and asset management; Alibaba Cloud, China’s leading Infrastructure as a Service (“IaaS”) company; ele.me, a local services business; as well as numerous earlier stage businesses. In aggregate, these businesses are loss-making. As a result, Consolidated Group EBITA is lower than marketplaces EBITA at RMB 170 bn.

What is the Investment Case?

The investment case in Alibaba is straightforward. Its core marketplaces business is a wonderful business. It is highly profitable with an underlying operating margin of 75%. It can grow without committing much incremental capital. It is protected by numerous entry barriers including a massive installed customer base, network effects, and a thriving ecosystem. And it is likely to grow in the low to mid-teens for the foreseeable future driven by the growth in online consumption in China.

In addition, Alibaba has various other businesses. Not all of these are likely to prove valuable. I am sceptical of its efforts in new retail (Freshippo, community group buying) as well as local consumer services (ele.me) and international marketplaces (Lazada). However, losses there are likely to be dwarfed by the profits from the more promising businesses, such as Ant and Alibaba Cloud.

Based on Alibaba’s marketplace-based core commerce adjusted EBITA of US$ 35 bn, its marketplaces business can be bought at a low to mid-teens multiple of its underlying profit. This is far below the average market level for what is almost certainly an above average business and far below what might be considered appropriate for a business with its profitability and growth profile.

In addition, Alibaba owns a 30% stake in the Ant Group. Ant is one of two leading digital payments companies in China (the other being Tencent) and, according to its prospectus, one of the leading distributors of consumer and small business loans, insurance and money market funds. At the time of its IPO, Alibaba’s stake was valued at US$ 100 bn. It remains to be seen where the business shakes out when the regulatory dust settles, but as I argue below, not all changes need prove negative in the long run.

Alibaba also owns Alibaba Cloud, the third largest IaaS company in the world (behind AWS and Microsoft) with over RMB 60 bn of revenue in FY2021. If Alibaba Cloud follows the same trajectory as AWS, it could easily become as valuable as Alibaba’s marketplaces business today. It is due to turn profitable this year, so it is on the right track.

What Do I See Differently?

-

Alibaba is not Jack Ma

The perception in the West tends to be that Jack Ma and Alibaba are one and the same thing. Leaving aside that Jack Ma announced his retirement from Alibaba in September 2018, it overlooks Alibaba’s highly unusual management structure and the role it has played in the Company’s success. Alibaba is structured as a partnership with 38 active partners. It reflects the spirit of partnership that has been a cornerstone of the Company’s culture from the earliest days. It has bequeathed the company with multiple founders, not just one.

-

The E-commerce business is not impaired

There is a perception that Alibaba’s marketplaces business is impaired based on the faster growth of newer entrants such as Pinduoduo, ByteDance, Tencent mini programs, and Kuaishou. They are growing faster because they are younger businesses addressing the comparatively under-developed market for discovery-based e-commerce, i.e., when customers do not yet know what they are looking for. Alibaba is a more mature business that dominates the more established search-based e-commerce.

I remember a similar debate playing out in the West in the mid-2010s when Facebook’s business started to take off. The consensus was that Facebook would disrupt Google’s search business by capturing demand in the discovery phase. Articles on “Peak Google” abounded. In the end, Facebook did indeed grow faster than Google (starting from a lower base, of course), but Google also did fine. I have no doubt that things will play out similarly in China. When the consensus is that online search is an awful business to be in, it is a sure sign that Mr. Market is in a foul mood.

-

The postponement of the Ant IPO makes sense

To my mind, the postponement of Ant’s IPO and the subsequent changes that the company has been required to make to its business model make total sense. According to its prospectus, Ant Group originated loans to half a billion people in China and accounted for nearly a fifth of the country's outstanding short-term consumer debt as of June 2020. Meanwhile, roughly 100 Chinese banks had the equivalent of US$ 230 bn in outstanding consumer loans underwritten primarily by Alipay, a company that was unregulated, carried no financial risk if the loans turned sour, and had no capital requirements. This was a disaster waiting to happen and was untenable from a regulatory perspective. I have no insight into what role Jack Ma’s injudicious comments on Chinese regulators had in accelerating and hardening their response, but I have no doubt that change was inevitable anyway. Potential shareholders in Ant can be thankful that regulators did not wait until after the IPO to announce their actions. It was a shareholder-friendly move for which they have received little credit.

As a result of the changes, Ant will most likely have to retain 30% of the loans it intermediates and hold appropriate levels of capital against them. The consensus is that this makes the business less valuable as it will slow down growth and bind greater levels of capital. This may turn out to be the case, however it may also make the business more valuable in the long run by better aligning the interests of consumers, banks and Ant around responsible lending and ensuring that Ant is appropriately capitalised to withstand periods of economic volatility.

-

The Chinese Government is not out to destroy its internet champions

As per my earlier discussion on regulation in China, I do not believe the purpose of regulation is to destroy companies like Alibaba to settle personal vendettas with rogue founders. My view is not based on a unique insight I have on the machinations of the Chinese government but on analysing the substance of regulation (as opposed to the commentary on it in the Western press). Whilst it is for sure debatable whether regulation will have the intended consequences, the intent is, in my view, rational and well-meant. The discussion around the regulation of Ant above illustrates this point well. Moreover, regulation has been evenly applied. It is not just directed at single players and has included Tencent, which is by all accounts a model student.

Of course, anti-monopoly regulation impacts the larger players more by its very definition. However, if it places said businesses on a more sustainable footing by aligning them more closely with Society’s goals, it may not be a bad thing. If regulation succeeds in this aim, it may prove to be a forerunner of what happens in the West. Given the obscene take rates on payments and e-commerce transactions here, I certainly hope so.

-

Earnings power is real

A further criticism of Alibaba is that the accounting does not reflect the underlying economics of its business. I have sympathy with the argument that some non-GAAP figures are ambiguous. GMV is notoriously difficult to calculate due to returns, fake accounts, and phantom transactions. Moreover, two reasonable people might disagree on how costs ought to be allocated between business units, what is one-off vs. recurring, and which costs are effectively operating rather than investing in nature. At a high level though, it strikes me as highly implausible that the dominant e-commerce marketplace in the world’s most populous country is not spectacularly profitable. The extent of said profitability might reasonably be debated but not its existence.

-

Mega caps can be mispriced

There is a school of thought that only smaller companies can be mispriced, the idea being that smaller companies are less well understood than larger ones. This is not my experience. I remember hearing similar arguments when I invested in Google in 2012 as it was going through the mobile transition and Facebook in 2016 when it was facing regulatory headwinds (still is for that matter).

My experience is that there is never a shortage of motivated people trying to uncover the facts at all companies of all sizes. What occasionally happens, though, is that a consensus develops around those facts (“Google won’t work on mobile;” “Facebook will be shut down by regulators”) which creates the opportunity to take a contrarian view. If anything, their size hardens the consensus given that larger companies attract round-the-clock news coverage whereas small companies do not. Of course, this does not mean that every investment in a large company is guaranteed to work. But it is not guaranteed to fail either.

Part 5: A New Investment in Salesforce.com

The assertion that mega caps can also be mispriced is a good segue to our second new investment in Salesforce.com. Salesforce is one of the largest software companies in the world with a market value of around US$ 250 bn. It is best known for its customer relationship management or “CRM” solution, known as its Sales Cloud. It has three additional clouds (“Service,” “Marketing” and “Commerce”) as well as a thriving platform business with both owned and 3rd party software solutions.

I first came across Salesforce in 2013. I was invested in Bechtle, a German company that provides companies with their in-house IT. I kept hearing about a strange new concept called “the Cloud” and wanted to get up to speed on the topic in case it was a risk to Bechtle. As a result, I picked up a copy of “Behind the Cloud”. It documents how Salesforce.com pioneered cloud-based software and revolutionised the software industry.

Since then, I have followed Salesforce from a distance and visited it several times in San Francisco. I did not consider it seriously as an investment though as for much of the period, I had not yet overcome my aversion to loss-making companies.

This changed in December last year when Salesforce announced the acquisition of Slack (a former investment of the Business Owner Fund, described in my 2020 half-year letter) for US$ 27 bn. On the date of announcement, Salesforce’s market value fell by around US$ 20 bn. Effectively, the market was saying that Slack was almost worthless, which, as an enthusiastic owner of Slack, I disagreed with. Initially, I decided to keep our Slack stock and roll it into Salesforce (as part of the consideration was in Salesforce's own stock). As Salesforce’s price fell further in the subsequent months, I bought its stock directly to make it a full-size position post the closing of the Slack acquisition.

Why Are We Invested?

Salesforce has all the ingredients that I look for in an investment: a passionate owner operator that leads by example; a wide and growing moat, and an attractive valuation.

Marc Benioff

Salesforce is led by Marc Benioff, the company’s founder and large shareholder. Benioff co-founded Salesforce in 1999 by launching a revolutionary CRM software solution. What made it revolutionary was not the software itself but the fact that all the software and critical customer data were hosted on the Internet and made available as a subscription service. The “software as a service” or “SaaS” model was born.

I recall wondering whether SaaS was such a big deal. After all, it was already possible to host data at an application service provider and convert a onetime licence fee into a monthly payment through leasing. It was, as I discussed in my 2018 investor letter. SaaS transforms the relationship between the software provider and the customer, and the customer and other software providers. On the former, it better aligns the software provider and the customer, as the more successful the customer is, the more software it buys. On the latter, it makes it trivially easy to add 3rd party software. It is clear from Benioff’s earliest letters that he grasped this from the beginning. For example, Salesforce pioneered the “customer success” organisation as well as the “app store”. Benioff is a visionary leader.

Benioff is also a values-driven leader. In "Trailblazer,” Benioff’s most recent book, cowritten with Monica Langley, Benioff describes how Salesforce decided from the beginning to orient its culture around values. These values were “trust,” “customer success,” and “innovation” with “equality” later added as a fourth. It also sets aside 1% of the company’s equity, product, and employee time, an initiative called the “1-1-1 philanthropic” model. I love to see leaders who lead through values as opposed to fiat. It empowers employees and is best for customers. Or, as Benioff more succinctly puts it:

Values create value

A Wide and Growing Moat

Like all software companies, Salesforce benefits from switching costs. Once customers install a software, it is costly and disruptive to replace, making them reluctant to switch providers. Of all the moats though, switching cost is the one I like least as it tends to make incumbents complacent and lazy. It may guarantee short term success but also long-term failure. What I love about Salesforce is that it has multiple other moats.

Most importantly, it has a culture that it is firmly rooted in customer success. Salesforce quite literally pioneered the customer success organisation that is now standard in the industry. A focus on customer success creates strong alignment between the customer and Salesforce as Salesforce knows that the bigger customers become, the more software they buy. It also serves to counteract the negative ramifications of switching cost without diminishing any of its benefit. The best thing about culture is that it becomes more entrenched over time as it becomes part of a company’s DNA.

A further important moat is the ecosystem whereby Salesforce’s platform is enhanced and enriched by a network of software companies and IT service providers that have built their companies on Salesforce’s platform. This includes large companies like Veeva (which has a solution for the healthcare vertical based on Salesforce) as well as thousand of smaller providers in the app store. It also includes the world’s largest IT consultants. This moat also grows over time as the richer the ecosystem, the more customers it draws in, which draws in more service providers in a virtuous circle.

Another moat is the Company’s brand. In many verticals, Salesforce has dominant market shares. As such, it is the default option for most companies as employees switching between companies will likely already be users of Salesforce. I have also heard anecdotally that younger companies prefer Salesforce to a lighter solution so that they have a solution that they can grow into.

The network effect is also a source of moat. There are likely multiple network effects in the business. An important one is data network effects. Salesforce is increasingly implementing AI to automate certain marketing tasks, e.g., which lead to call first. This improves over time as every interaction can be used to optimise future interactions.

An Attractive Valuation

The price we paid for our stake in Salesforce is compelling in my view. Based on the assumption of US$ 26 bn revenue in the fiscal year ending Jan 2022, we paid around 8x revenue. The company has unit economics, i.e., the profitability of existing customer relationships excluding marketing investments in new customers and other growth costs, of 40%. This implies a multiple of 20x pre-tax operating earnings. For this, we receive a company that can grow mainly organically at 18% p.a., based on its target of US$ 50 bn revenue in FY2026. This strikes me as a compelling valuation in absolute terms as well as compared to the average market valuation.

What Do I See Differently?

The above analysis, I suspect, is well understood by the market. So, what do I see differently?

-

The Slack acquisition makes sense

Slack’s ambition is to create a network which not only connects companies internally, but also connects them externally to customers and suppliers through Slack Connect. My strong belief is that the chances of realising this vision are greatly increased by becoming part of Salesforce. Salesforce is ideally placed to help Slack penetrate large enterprises as well as front office workers, two areas of historical weakness at Slack. If Slack can become the de facto network connecting most of the world’s knowledge workers at $10 per seat per month, it will be a Microsoft Office-sized business. Slack is an enormous free option embedded in Salesforce.

Furthermore, Slack adds enormous value to Salesforce. It creates a front end that can be used to tie together all Salesforce’s other clouds making them more valuable from a customer perspective.

-

Salesforce is a good capital allocator

I disagree with the idea that Salesforce is an undisciplined capital allocator. My thinking on the Slack acquisition is clear. MuleSoft and Tableau, its two largest acquisitions prior to Slack, have been run away successes financially. In the most recent quarter, revenue was growing at MuleSoft and Tableau at 39% and 22% respectively. In addition, they strengthen the overall Salesforce ecosystem. Tableau was in 9 of Salesforce’s top 10 deals and MuleSoft was in 8.

-

Salesforce is not an unfocused conglomerate

A clear line can be drawn between the strategic priorities laid out by Benioff in the company's earliest years and subsequent acquisitions. For example, in the company’s 2005 annual report, Benioff underlines the importance of integrating data from existing enterprise applications, anticipating the MuleSoft acquisition. In the 2011 report, Benioff declares the next decade to be “social, mobile and open” and launches Chatter, a chat application anticipating the acquisition of Slack. In both cases, strategy preceded acquisitions by over a decade.

Overall, I am delighted to be invested in Salesforce and look forward to tracking the company's progress in the coming years, in particular with regards to Slack.

The 2022 Annual Gathering

The 2022 RV Capital Annual Gathering is scheduled to take place on the weekend of 15-16 January 2022. I am planning on opening registration shortly. I have no idea what restrictions around travel and large events will be in place next January, but by allowing you to register, I can at least remove the uncertainty of whether you have a place or not. I sincerely hope we can all get together. It has been too long.

All the best,

Rob