Whitney Tilson’s email to investors discussing KHC analysis and feedback; Why Buffett won’t buy it.

I got some incredibly insightful feedback about KHC from Friday’s email. While some of it is positive toward the company and 3G, most of it isn’t.

Q4 hedge fund letters, conference, scoops etc

In my view, the skeptics make far more persuasive arguments and this, combined with the financial analyses I share below, has caused me to flip my view nearly 180 degrees regarding whether Buffett is likely to buy all of KHC: I now think it’s highly unlikely. To understand why, read on…

1) One friend wrote: “Did you look at KHC's 10K? Check out free cash flow for the past three years. Nowhere near that $7b of EBITDA.”

So I did – and he’s right: the story is grim.

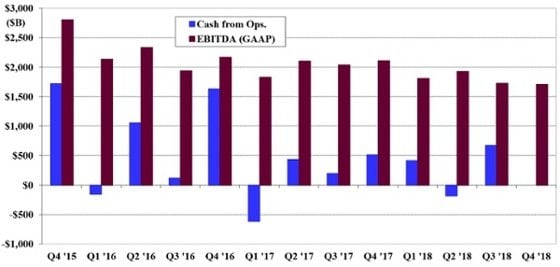

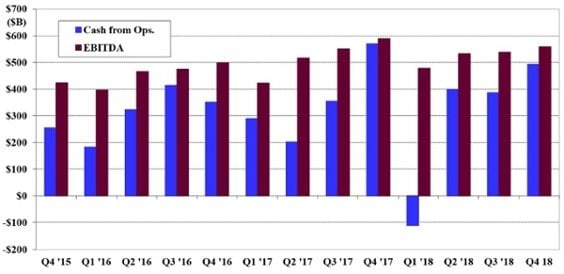

Let’s start with this chart I put together, which shows the company’s operating cash flow and EBITDA for each quarter since Q4 '15, right after the Heinz merger took effect (note that it only includes EBITDA for Q4 ’18, as the company’s earnings release didn’t include a cash flow statement; I hate it when companies fail to include this):

The divergence between operating cash flow and EBITDA is vast: in total, from Q4 ’15 through Q3 ’18, KHC reported $24.9 billion of adjusted EBITDA yet only produced $5.8 billion of operating cash flow (77% lower).

This is just weird. EBITDA should be larger than OCF since growing inventories/working capital consume cash, but not four times larger!

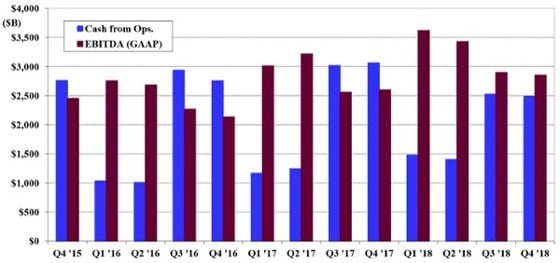

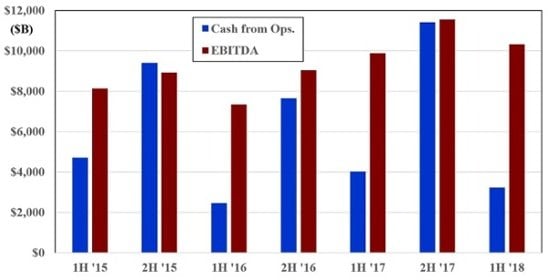

I wondered what these figures might look like at comparable companies so I first pulled the data for Unilever (which KHC tried to acquire in 2017). This looks like what I’d expect, with cumulative EBITDA of $36.5 billion vs. $26.9 billion of cash flow from operations (25% lower):

Then I looked at Mondelez, which has cumulative EBITDA of $14.5 billion vs. $11.7 billion of cash flow from operations (19% lower):

Finally, I looked at two companies controlled by 3G, ABInBev and Restaurant Brands International, and neither looks unusual. Here’s BUD, which has cumulative EBITDA of $65.2 billion vs. $42.9 billion of cash flow from operations (34% lower):

And here’s QSR, which has cumulative EBITDA of $6.4 billion vs. $4.1 billion of cash flow from operations (36% lower):

All four of these companies look normal, in stark contrast to KHC…

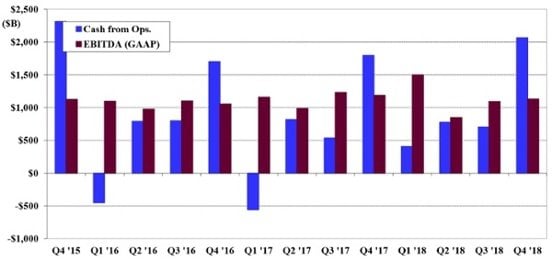

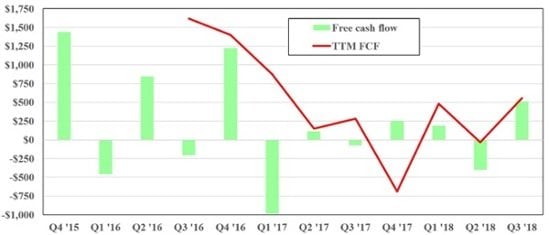

Getting back to KHC, this chart shows free cash flow (OCF – cap ex) by quarter and trailing 12 months:

You can see that there were three big quarters for free cash flow after the merger closed, but free cash flow has been nothing short of a disaster for the last two years.

This chart is stunning to me. Analysts (myself included on Friday – shame on me) are valuing KHC based on $7.1 billion of “adjusted EBITDA” for 2018, but TTM free cash flow is a mere half billion!

2) Enrique Abeyta emailed me:

My views on KHC (and several other similar companies in the consumer product space) remain unchanged – ALL of the legacy consumer product companies that have traditionally benefited from scale are being – and will be further impacted – by the impact of technology on marketing, production and distribution which is allowing the market entry of thousands of competitive products.

From here things will not get any better and perhaps get much worse.

The worst positioned are those that took on a “private equity” model predicated on high leverage, stable low growth and cost-cutting. This financial approach is eerily similar to the approach taken by the newspaper companies in the mid-2000s and when “stable low growth” turned into a -30% revenue decline that led to an erosion (or complete destruction) of the equity “stub” on these highly levered companies.

I also think these disruptive forces are impacting media and telecom as well (hence my bearishness on AT&T, my favorite short among these, as well as Disney).

For a fun exercise, just put together a list of the top companies in these three sectors (above $25b market cap) and rank them by leverage (EV/EBITDA) highest to lowest and there you have your hunting ground.

At this point, I believe that there is NO solution that doesn’t involve further pain for equity holders. It is just a matter of whether managements are willing/able to inflict a medium amount of pain to save the (equity) patient or will they be willing to take little or no pain and end up with BIG losses. History points to the latter…

There is going to be a LOT of equity value destruction here in the next 5+ years, regardless of the economic environment.

3) Another friend wrote:

For several years I lectured at [a top] business school on the 3G model, going back to the history of AmBev through the acquisition of AB (but before the SAB Miller and Modelo deals). I would argue that the 3G model isn't the issue; the issue is that they chose industries where organic growth secularly changed to become a headwind.

The reason is that if one goes back to the original AmBev deal, and even to the InterBrew acquisition before the AB deal, 3G grew revenue/hectolitre of beer at healthy rates, and well above costs/hectoliter; in other words, they could increase pricing and mix through product innovation (called premiumization) and investing more aggressively at point of sale / distribution. This is part of the playbook.

Starting with AB, the beer mainstream beer industry has lost significant share to craft beers and alternative adult beverages; for KHC, the trends away from processed foods has accelerated in the last five years.

The traditional 3G model was to find inherently good businesses that had historically demonstrated pricing power which, because they were good businesses, had complacent cost structures, whereby 3G could expect to continue with the secular organic growth, invest in marketing / product development and then aggressively cut costs. The investing in marketing & product development is core to their bible, "How to Double Your Profits in 6 Months or Less" by Bob Fifer, where costs should be ruthlessly reduced where they do not add value in order to outspend on costs that drive revenue. Within the last year, Jorge Paulo Lemann admitted that his CPG businesses were getting disintermediated and this was something they hadn't seen or expected several years ago.

4) Another friend wrote:

I highly doubt Buffett will take KHC private. Where do people come up with this stuff??!!

Buffett came into this with very advantageous terms (prefs yielding 9%). Those are the same terms he was getting in distressed financial companies in the crisis. I would always ask why 3G would give him such a sweet deal in a cheap money world? The answer is that they considered it temporary capital. Buffett allowed them to move very fast. Yes, it was an expensive piece of paper but they would plan to take him out as soon as they could three years later when "adjusted EBITDA" was higher, and they could refinance into straight debt, which is exactly what happened. I suspect Buffett has zero interest in paying a premium on a levered entity with no top-line growth.

I know the consumer space well. Would this have happened without 3G? Yes. The fundamentals are not good. 3G took potential future returns and (temporarily) brought them to the present (lever up and raise margins). So the pattern would have been different, but the ending place similar. Part of the KHC unwind is significant multiple contraction from levels that never should have existed in the first place (everyone got excited because 3G would eventually buy everything).

3G is like private equity but with one difference: 3G likes to lever up and cut costs but they're buying for keeps not to flip so I think they genuinely believed in the plan. I think they just completely misjudged how tough it would be to grow (in beer also) and bought into their own “adjusted EBITDA” nonsense. Notice also that the financials they report are filled with adjustments and it's hard to follow the true cash generation. I think it's telling that net debt is actually up since they put Kraft and Heinz together in 2015. I think the Street was giving them way too much leniency on adjusted EBITDA, they were almost able to use that to keep the game going.

P.S. – Here’s my calculation of Buffett's investment:

- 2013: Heinz deal to go private - invested $4b in common and $8b in 9% pref = $12b investment

- 2015: In the Heinz-Kraft merger, BRK puts in another $5b (3G also put in another $5b)

- 2016: Prefs on original Heinz deal gets called, BRK receives $8.35b (plus received $2.16b in preferred dividends over the three years, almost tax-free)

- So Buffett put in $12b and took out $10b+, and then re-upped for another $5b (shouldn't have written this last check)

- Ever since then, he's owned 25% which after the implosion is worth $10B+

Does Buffett like the 3G guys? Yes he did. Has his enthusiasm dampened? I'm sure. My point of the above is he didn't necessarily love the idea of LBO'ing consumer companies, he just likes 3G (less so now) and his original entry price was mostly in the form of a special pref deal.

5) Another wrote:

The blowup in KHC's stock price is certainly interesting. I don’t own it or know much about it, but I want to question why these would be the two potential conclusions: “is the problem primarily the fault of the 3G model (cost-cutting that goes too far, not just fat but muscle and bone, plus too much debt), or did they just buy the wrong assets, in the wrong industries?”

3G gets a ton of focus for cost-cutting, and that’s certainly real. But these guys play as much, or more, offense as defense – I don’t know KHC, but I’ve looked at Ambev hard over the years, and their constant push on offense, in every dimension, is incredible. You simply can’t compile the long term records they have as operators with cost cutting, and I firmly believe Buffett partnered with them, more or less permanently, for offense, not defense.

And before we conclude that cost-cutting is causally at fault, how about (a) some specific example of products that were starved of advertising, or of line extension, or of stocking efforts, with such-and-such outcomes; and (b) I’d want to compare various of their products to other CPGs (strong brands vs strong brands, or weak brands vs weak brands, comparable products, etc.) that supposedly have not engaged in this bone- and muscle-cutting. Because the fact is, it’s a tough new world for CPGs, and the new realities of consumer behavior, retailing and so on seem like better explanations than muscle-cutting execution (does anyone think that Oscar Meyer’s challenge today is . . . poor execution)? I’d be riveted by a knowledgeable, articulate discussion of those kinds of facts – I wish I knew more about it.

And isn’t your second possible conclusion really better asked as “did they overpay?” They bought businesses that faced certain challenges. Isn’t that what we do when we invest? Were these the wrong assets such that no one should have paid any price for them? I don’t know the answer, but that seems like a better question.

6) Another wrote:

The problem is that CPG companies keep increasing prices, exposing them to be undercut by cheaper brands OR giving pricing power to niche brands. You never want to anchor the middle of the market. Decades of price increases did this.

Compare with McDonald's value menu. It leads the industry by design.

These unnecessary CPG annual price increases now lets them get undercut by generics but also makes the price of a perceived upgrade palatable. Illustrative example: generic paper towels cost $2, Bounty costs $4, Seventh Generation costs $5.

If you think Bounty is worth the $2 premium, then maybe you think the cachet and environmental "superiority" of Seventh is worth the extra $1.

But if Bounty was $2.50 they'd crush both the generics and Seventh. The 50 cents is worth it but the $2.50 jump isn't.

This is EXACTLY what's happened with craft beer: the macrobrews increased prices so much that the "craft premium" became very small.

Be wary of executives blaming trends they plan to address when the reality is that "we priced too aggressively and can no longer get away with it."

VERY interesting on Berkshire possibly acquiring KHC. 2 items:

- Kill the dividend and delever quickly, or

- In a snap, the interest rate on the debt plummets once backed by Berkshire, which would lead to higher cash flow instantly.

7) Another wrote:

What the crazy drop in KHC stock showed today is that no management/company can cut its way to greatness and higher investment returns over time. What the financial press fails to acknowledge is that 3G treats the lives of their workers as a budgeting expense and nothing more.

As proof, consider that KHC consistently rates as one of the worst companies to work for according to Glassdoor (What are the worst companies to work for? New report analyzes employee reviews), which is very unusual given its large size compared to the others on the list.

3G reminds me of Jack Welch: lionized by investors and the press but no knack for innovation and growth – just cost cutting and financial engineering.

The 3G formula for me equals Gouging employees + Gorging on Debt + Growing through financial trickery.

8) Lastly, I had an interesting conversation with a friend:

Me: I assume KHC is still not even close to cheap?

Him: How do you define cheap? On Bloomberg it screens at 13x earnings. For a piece of sh*t with sh*tty brands, zero growth, zero chance of ever growing... I wouldn't want to own this at any price. There's huge opportunity cost. Any capital deployed to this can be better deployed in 100 other situations where the capital will be worth multiples over the next 10 years. Chances of that happening at KHC are pretty slim.

As an illustration, Buffett should have piled into the MasterCard and Visa IPOs, right? He knows the payment industry. If he had piled into MA in 2013 instead of KHC, we would be up 4x (300%) including dividends, 27% per year compounded. That shows the huge opportunity cost of a sh*tty investment.

Me: The question I'm struggling with is: is KHC's implosion primarily the fault of the 3G model (cost cutting that goes to far, not just fat but muscle and bone), or did they just buy the wrong assets (highly processed, unhealthy foods)? Would the outcome have been similar had Kraft and Heinz remained independent?

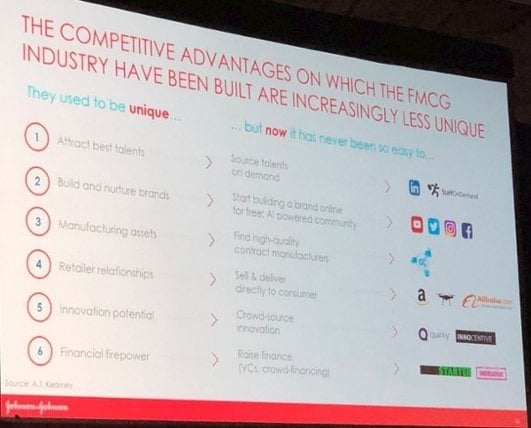

Him: The entire industry is screwed. This is a symptom of a broader problem. In very simple terms, the internet turned scarcity into abundance. The cycle for CPGs used to be: create product (say, Tide detergent), advertise on mass media (TV, radio), housewife goes to supermarket, Procter & Gamble pays slotting fees and endcap fees, she performs brand recognition from the commercial she watched, picks up Tide, and $$$. Rinse and repeat. Advertising was hard, very few could do it. Shelf space and distribution were scarce. P&G had a huge competitive advantage and barriers to entry.

What did the internet do? Blow it all apart. Advertising is no longer scarce; anyone can do it on YouTube and Instagram. Distribution is no longer hard; anyone can sell on Amazon. The shelf space is no longer scarce; it's infinite. All of those competitive barriers at the margins are gone. Now, combine this with tired brands from the 60s that haven't evolved to changing consumer tastes (Kool-Aid, Velveeta processed cheese, etc.), and you have a really bad combo. At least Nestle has a better portfolio (coffee is growing nicely) and Unilever has personal care, but KHC's portfolio SUCKS.

The poster child for this phenomena was Dollar Shave Club – check out this video. Blades made in Korea, direct-to-consumer distribution, free advertising on YouTube. They got 15% of the market share from Gillette seemingly overnight.

Me: So you think it's NOT a 3G problem? The counter-argument is: 1) P&G stock is at an all-time high; 2) my gut is that it's hard to imagine that Kraft and Heinz would be in as bad a shape as they are if they'd remained independent.

Him: Don't look at stock prices, look at fundamentals. P&G had $76b in sales in 2007, now it has $67b. Free cash flow has been flat for over a decade. Sales are totally anemic - up 1.8% last year, 0.4% growth expected this year. Share count is down a lot. To me this is knee-jerk thinking that this is still a staples business, whereas in reality it's not.

Me: Surely you're not arguing that P&G is as bad off as KHC and that investors are simply nuts?

Him: Like I said, different portfolios. P&G has personal care, home care, etc. But ALL the CPGs are experiencing the exact same competitive problems foisted upon them by the internet. The moats are narrowing for the reasons above, for all of them. And like I wrote about Unilever, if you have a kickass portfolio, you'll do better.

And yet, even Unilever has totally flat sales (down 5% last year, expected 1.8% growth this year).

And yes, I do think investors are nuts.

Check out this slide from J&J at last year's Consumer Analyst Group of New York conference – it was a funereal atmosphere. I was there.

9) Finally, a friend pointed out that KHC only has a float of ~300 million shares – and 135 million traded on Friday, 20x normal volume. That’s quite a turnover in the shareholder base!

10) Here’s a front page story from yesterday’s WSJ: It Shook the Food Business by Snagging Burger King, Kraft and Heinz. Now 3G Is Reeling. Excerpt:

3G Capital burst onto the business scene a decade ago when it spent billions to buy America’s old-school food companies, including Heinz and Burger King, and then relentlessly cut costs, including mass layoffs, to create efficient production machines.

Investors, including Berkshire Hathaway ’s Warren Buffett and hedge-fund owner William Ackman, expressed admiration for the Brazilian investment firm’s prowess. Headlines hailed its single-minded ability to improve profit margins. Rival companies followed suit, in some cases out of fear 3G’s founders would buy them to further bolster its lineup of storied brands, which includes Kraft Macaroni & Cheese and Bud Light.

Now, after transforming the American consumer landscape, 3G’s financial strategy appears to be running out of juice.

Investors can’t say they weren’t warned:

The firm’s top executives themselves sounded the alarm on the shift last year. “I’m a terrified dinosaur,” said 3G co-founder Jorge Paulo Lemann at the Milken Institute conference in April. “I’ve been living in this cozy world of old brands [and] big volumes. You could just focus on being very efficient and you’d be OK. All of a sudden we are being disrupted in all ways.”

He added: “We bought brands and we thought they would last forever. Now, we have to totally adjust to new demands from clients.”

… “If you go to a supermarket, you see hundreds of new brands,” said Mr. Lemann at the April conference. “In beer, we had the new kinds of beer coming in from all over. We are running to adjust.”

11) One more WSJ article: Key Brands Pay Price of Kraft Heinz Cost-Cutting. Excerpt:

Michael Lavery, an analyst at Piper Jaffray, said he has lost confidence that Kraft Heinz can successfully manage big brands to compete in the changing consumer environment.

“These impairments validate fears that Kraft Heinz may have been more focused on costs than on building brand equity,” he said. “Even if management has now seen the light,” he said, its brands are likely too damaged to drive growth in a sustainable way.

… Its outsize attention to making factories more efficient and reducing corporate head count may have failed at keeping its brands relevant and instead led to a permanent loss of consumers, according to analysts. Its approach also has hurt the company’s ability to compete for prime shelf space at supermarkets, they said.

Lately, Kraft has been under pressure to address those issues by lowering its prices, especially to compete with store brands, and by spending more on marketing and new product development. Last year, record-high supply-chain costs also ate away at its margins. The company expects its profit to continue deteriorating this year.