Baruch Lev is the Philip Bardes Professor of Accounting and Finance at the Stern School of Business, NYU. This article first appeared at the Lev End Of Accounting Blog and is shared here with his permission.

Today’s Wall Street Journal published an article that caught my attention: “Next Up: The Forgotten Earnings Season.” The article opens: “Only once before have U.S. earnings expectations risen so far, or so fast, as they have this year. Yet, investors couldn’t care less as shares are down. The result is that Wall Street’s favorite valuation measure has fallen at a speed usually only seen in a crisis… Yet rarely have investors shown so little regard for an earnings season than for the one starting in earnest on Friday.”

The article’s author seems surprised by investors’ disregard for earnings, and tries to provide explanations: “Perhaps they [investors] just dismiss the [earnings] forecasts.” Or, “Stocks had a huge run-up … Shareholders quickly priced in the benefits of lower corporate taxes while analysts waited for company guidance…” Perhaps? Perhaps not? These are speculations.

I think the reason for investors’ disregard of earnings is that they finally realize what I have been saying for several years now: reported, GAAP-based earnings no longer reflect corporate performance and future prospects (see, The End of Accounting, Wiley 2016).

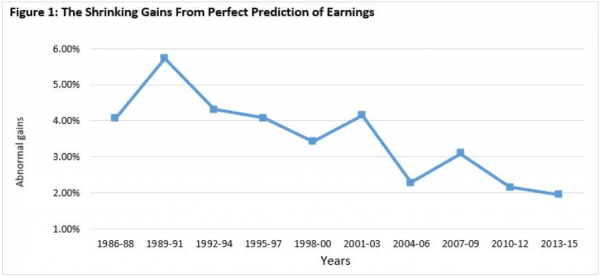

The clearest proof, yes proof, not speculation, that earnings don’t matter much anymore was provided in a recent research paper in the Financial Analysts Journal (“Time to Change Your Investment Model,” Fourth Quarter 2017). In this paper, Feng Gu and I provide the ultimate test of earnings’ usefulness to investors. We ask: what will you gain from a perfect prediction of earnings? We compute year-by-year gains from predicting all the U.S. public companies which will exactly meet, or beat the quarterly consensus estimate. We invest in these companies (retrospectively, of course) three months before the earnings release, and liquidate thereafter. The figure below portrays these average gains from 1986 through 2015.

It is clear that in the late 1980s and early 1990s these market and risk-adjusted perfect prediction gains were very high: 6% for three months, or 25-26% annualized. But the gains plummet since the early 1990s, and today, they are no higher than those from “momentum investing” (simply investing in stocks which gained in the past 6-9 months).

Why did reported, accounting-based earnings lose their value to investors? In the “old days,” earnings were computed by subtracting from revenues (sales) real expenses, like cost of sales, sales commissions, administrative expenses and interest. Investments, at that time mainly in tangible assets (property, plant, equipment, structures) were capitalized (recognized as assets) and, therefore, didn’t affect earnings. Such earnings truly reflected enterprise performance.

Today, in contrast, a large portion of accounting expenses aren’t expenses at all. They are really investments. These are all the massive corporate investments in intangibles: R&D, brands, information technology, etc. These intangible investments, surpassing $2 trillion annually in the U.S., are expensed in the income statements. And this is not just for technology and science-based companies. Intangibles, such as information technology and customer acquisition costs are shared by most non-tech companies and they are also expensed.

The result are deeply flawed reported earnings that often misrepresent enterprise performance. Kite Pharmaceutical, for example, a cutting-edge biotech company, reported hundreds of millions of dollars losses every year from R&D expensing, until it was recently bought by Gilead Sciences for no less than $12 billion. So much for earnings.

Add to this the multiple one-time earnings items (assets and goodwill writeoffs, restructuring charges, etc.) that have nothing to do with current operations, and the constantly increasing number of subjective managerial estimates affecting earnings―all courtesy of the FASB―and you get a rather meaningless number called earnings, which investors finally learned to ignore.

So, I am not surprised that “investors couldn’t care less” about earnings, quoting the Wall Street Journal. I predicted that this will happen years ago.

But if reported earnings are largely meaningless, how should investors value securities? We discuss it in the Financial Analysts Journal article referenced at the beginning of this blog, and I will write about it in forthcoming blogs, starting with a new way to evaluate customer franchise, which for many companies is their major value driver.

Professor Lev is not affiliated with Knowledge Leaders Capital and his opinions are his own.

Article by by Baruch Lev, Knowledge Leaders Capital