Broyhill Asset Management annual letter for the year ended December 31, 2017; titled, “Hilariously Rich.”

For the year ending December 31, 2017, Broyhill generated low double-digit returns across the majority of our separately managed accounts. Performance of more mature relationships closed the year at the high end of this range, while returns for newer relationships, where we are still actively deploying capital, ranged from mid-to-high single digits. Detailed quarterly reports, including account and benchmark performance, portfolio holdings, and transaction history, have been posted to our investor portal. 1

Check out our H2 hedge fund letters here.

While we are pleased to report attractive absolute returns and profitable results for the year, our performance fell short of the strong gains posted by equity indices. We made money for everyone. And for the most part, our largest investments were our biggest winners on the year. We didn’t have any significant losers. But that didn’t mean we didn’t make mistakes. Our relative underperformance was primarily due to our lower than normal exposure to risk assets. The flipside to this is that we are also carrying a higher than normal cash position. This is unlikely to change until there is a significant shift in the opportunity set. Simply put, we will never own expensive assets in the hope of selling in the future to someone willing to pay an even more expensive price. We will not rely on greater fools, despite the market's increasing reliance on Idiocracy.

Speaking of greater fools, Everyone Is Getting Hilariously Rich and You’re Not.

Last year, all asset classes appreciated, every equity index rose in every quarter of 2017, and US stocks went up in every month.

In an environment like that, this job should be easy!

It might seem that the only requirement for making money last year was to roll out of bed in January. Yet, for some, it was an extremely challenging twelve months. For others, it was their most difficult year ever. Many of the most respected investors in the business struggled. A few completely threw in the towel. Below are just a few of the snippets we collected during the year.

Did this group of able investors simply forget how to make money last year? Unlikely. So why did so many talented managers struggle when all they needed to do was roll out of bed? And how did we manage to achieve acceptable results in the midst of such a challenging environment for value investors?

Simply put, we operate with a different mandate. The advantage of being located in the foothills of the Blue Ridge Mountains is that we are outside of the fray. Removed from the noise, we are able to climb the mountain and survey the investment landscape with a rational, objective, long-term perspective.

While many investors stumbled last year, we lived to fight another day. We also made our investors a good bit of money in the process.

Markets like this one may be incredibly frustrating, but we believe they also vindicate our strategy and staying power. Rather than attempt to call the top—or worse, fight the trend—we hold cash and hedge. Rather than speculate on when the bubble will burst, we will simply wait and position ourselves to pick up the attractively priced pieces.

Short selling serves an important purpose in financial markets, but it requires a certain skill set and natural programming that we admittedly lack. It also exposes investors to unlimited loss. Conversely, large cash balances, combined with cheap hedges (which limit our capital at risk), allow us to sleep a little better at night, while still tagging along for the ride in the morning.

While others struggle and scramble to cover shorts, we are better prepared if the speculative excesses continue. Although it’s clearly not our preference, we are happy grinding out acceptable returns while waiting for a larger margin of safety.

We recognize that we have no control over the economic climate or the market landscape. We can complain all we want, but it won't change a thing.

We are not betting on any specific market outcome, although we are quietly rooting for better prices. Until then, we are just trying to make as much money as possible, without sticking our necks out too far.

It's all too easy to be lulled into complacency when asset prices are marching higher to the beat of capital flows and momentum. But we must resist this temptation in order to survive the next cycle with our composure, capital, and confidence unharmed. We will make mistakes, and from time to time, our process is sure to produce suboptimal results. But over the long term, we believe this approach should yield superior capital growth while minimizing risk of loss.

We recognize and fully accept that our process may not be the best way to stay at the top of the pack in any given year. We are not designed to outperform in a bull market when asset prices are marching relentlessly higher.

In a bull market, aggressive risk-taking can easily be confused as intelligence. The challenge, for passive investors, will be to hold onto those gains when the tide goes out.

You don’t need Broyhill in a bull market.

A passive investment strategy (i.e., no investment strategy) can perform better. And it has. It is only in a bear market that Broyhill’s disciplined value-driven approach becomes a necessity, aiming first to protect capital before pursuing potential gain.

Over a full market cycle, we aim to produce above average equity returns with below average risk. If successful, excess performance should be driven by better-than-average performance in declining markets and average or below average performance in rising markets.

We report index returns to investors as a basis for comparison, but warn that short-term performance comparisons are inconsistent with long-term capital preservation.

Given our value orientation and aversion to loss, our hedge fund peers may serve as better short-term points of comparison. On that basis, Broyhill has added tremendous value. More so, on a risk-adjusted basis.

Consider that the average hedge fund maintained gross exposure between 150% - 200% of assets and gained 6.5% during 2017. In contrast, the majority of our clients enjoyed double-digit returns with less than half of their assets at risk in equities and a significant portion of that risk hedged via cheap index put options.

Bottom line: we generated nearly double the return of the typical hedge fund with a fraction of the risk for our investors. And we provided lower fees, daily liquidity, and full transparency along the way.

Everything Old Is New Again

When trumpets were mellow And every gal only had one fellow

No need to remember when 'Cause everything old is new again

Dancin' at church, Long Island jazzy parties Waiter, bring us some more Baccardi

We'll order now what they ordered then 'Cause everything old is new again

Get out your white suit, your tap shoes, and tails Let's go backwards when forward fails

And movie stars you thought were alone then Now are framed beside your bed Don't throw the pa-ast away

You might need it some rainy day Dreams can come true again When everything old is new again

Get out your white suit, your tap shoes, and tails Put it on backwards when forward fails

Better leave Greta Garbo alone Be a movie star on your own And don't throw the past away

You might need it some other rainy day Dreams can come true again

When everything old is new again When everything old i-is new-ew a-again

This is not the first time value investors have struggled. To understand the current challenges, one can obtain valuable perspective by looking backward because looking forward often fails. As the saying goes, “Don’t throw the past away, because you might need it some rainy day.” Everything old is new again.

On December 27, 1999, Barron’s published the article, “What’s Wrong, Warren?” The title suggested that Buffett may be losing his magic touch.2

Berkshire stock had just gone through a tough spell. Its market capitalization was nearly halved in the final years of the tech bubble. Over the same time, the Nasdaq gained 145% during its final surge. Buffett simply didn’t get it. He was too conservative. An old man out of touch with the new reality.

A few months later, on March 31, 2000, The New York Times published an article titled, “The End of the Game; Tiger Management, Old-Economy Advocate, is Closing.”

The financial markets humble ordinary investors all the time. In Julian H. Robertson Jr., head of Tiger Management, they have humbled an investing giant. After 20 years of generating superlative investment returns by buying stocks that were undervalued and selling short those that carried excessive valuations, Mr. Robertson, 67, confirmed yesterday that he was shutting Tiger's operations. He has essentially decided to stop driving the wrong way down the one-way technology thoroughfare that Wall Street has become.

In two short years, Tiger’s assets fell from more than $21 billion from its peak in 1998, to $6 billion. In his final letter to investors, Robertson, a veteran hedge fund manager, blamed his fund's problems on the rush to cash in on the Internet craze.3

Since August of 1998, the Tiger funds have stumbled badly and Tiger investors have voted strongly with their pocketbooks . . . the demise of value investing and investor withdrawals has been . . . stressful to us all . . . and there is no real indication that a quick end is in sight.

And what do I mean by, "there is no quick end in sight?" What is "end" the end of? "End" is the end of the bear market in value stocks. It is the recognition that equities with cash-on-cash returns of 15 to 25%, regardless of their short-term market performance, are great investments. "End" in this case means a beginning by investors overall to put aside momentum and potential short-term gain in highly speculative stocks to take the more assured, yet still historically high returns available in out-of-favor equities.

"Avoid the Old Economy and invest in the New and forget about price," proclaim the pundits. And in truth, that has been the way to invest over the last eighteen months . . . in an irrational market, where earnings and price considerations take a back seat to mouse clicks and momentum . . . logic, as we have learned, does not count for much.

I have great faith though that, "this, too, will pass." We have seen manic periods like this before and I remain confident that despite the current disfavor in which it is held, value investing remains the best course. There is just too much reward in certain mundane, Old Economy stocks to ignore. This is not the first time that value stocks have taken a licking. Many of the great value investors produced terrible returns from 1970 to 1975 and from 1980 to 1981 but then they came back in spades.

The difficulty is predicting when this change will occur and in this regard I have no advantage. What I do know is that there is no point in subjecting our investors to risk in a market which I frankly do not understand. Consequently, after thorough consideration, I have decided to return all capital to our investors, effectively bringing down the curtain on the Tiger funds. We have already largely liquefied the portfolio and plan to return assets as outlined in the attached plan.

Our current challenges are not new. We’ve lived through these conditions before. Yet, after twenty years, we all risk losing the benefits of a “beginner’s mind.” So, it’s helpful to go back and get a sense of what it must have felt like to have been “wrong” for that long. And to remember what it felt like to watch speculators around you get hilariously rich.

For the many investors who have not yet lived through a bear market, Ed Chancellor’s Capital Account is about as close as you can get to managing capital through the last speculative mania. The book, a collection of selected letters by Marathon Asset Management from 1993-2002, vividly illustrates how the investment community became obsessed with chasing short-term profits at the expense of long-term returns. More importantly, it serves as a priceless reminder that the outcome was entirely predictable for those who kept a disciplined, value-oriented approach.

Seth Klarman’s annual letters to Baupost Group shareholders during the final years of the tech bubble are worth their weight in gold. The similarities between then and now are eerily on display. Below are (more than) a few excerpts from Baupost’s 1998-1999 letters.

Bulls will patiently explain that it is different this time . . . of course, any contrarian knows that just as a grim present is usually precursor to a better future, a rosy present may be precursor to a bleaker tomorrow.

Investors have come to expect handsome returns from investing in equities, and money has been relentlessly flowing into U.S. stocks. We believe that this has in the short run become a self-fulfilling prophecy, as funds flows lift share prices to produce the profitable returns that investors have sought. Over time, however, this is very likely to become a self-defeating prophecy, as today's inflows lift share prices to levels from which the long term returns will likely be below the historical average, and even further below today's investors' bloated expectations.

Almost no one wants this Goldilocks economic environment to end. Not the public, which is willing to forgive their President almost any indiscretion. Not professional investors, who are shrugging off ominous warning signs. Not even hordes of formerly risk averse investors, who have seemingly adopted the Massachusetts State Lottery's slogan (you gotta play to win) for their new investment guidelines. Clearly, the greater perceived risk is no longer that of being in the market but rather remaining on the sidelines.

There has been a stampede to own a "nifty-fifty", several dozen widely admired companies seeming to promise an investment utopia of safety, stability, steady growth, and liquidity. Once again, no price is regarded as too high to pay for these characteristics. An illusion is created that owning these stocks is prudent, that not owning them is imprudent, and, lately, that owning anything else is downright irresponsible. Investors are strangely willing to ignore the moral hazard of their own behavior, rewarding managements which successfully manipulate quarterly earnings into a steady and predictable uptrend.

Part of the reason for the return to a nifty-fifty era has been the increasing use of indexing by large institutional investors . . . This has fueled more and more money going into the largest stocks, which have continued to surge while other parts of the market have slumped . . We believe the concentration of funds in a handful of stocks is in the process of creating a staggering opportunity amidst the neglected (or even totally ignored) thousands of smaller stocks.

Students of financial history can point to historic levels of valuation to suggest that we are in a bubble. But students of psychology may be needed to complete the picture. For one thing, the financial markets have been so strong for so long that fear of market risk has mostly evaporated. People who used to hold bank certificates of deposit now maintain a portfolio of growth stocks. It is not really within human nature to comprehend that you may not know everything you think you know, and, further, that what you believe in could change on a dime.

With more and more of the market value of U.S. equities represented by lofty multiples of current results, a change in sentiment could wipe out a large percentage of investor net worth. Sentiment, existing only in the

minds of investors, is subject to change quickly and without notice. Perhaps today's dreams will become realities for some of the current Internet and technology favorites; and perhaps not. For many, the dream will be replaced by a nightmare. Then, the escalating bill for betting on dreams rather than on realities will have to be paid up.

Real value, of bricks and mortar, finished goods inventories, accounts receivable, operating factories and businesses, and even brand names, is hard, although far from impossible, to destroy. If you don't overpay for it, your downside is protected. If you purchase it at a discount, you have a real margin of safety.

We believe a similar dynamic is at play today.

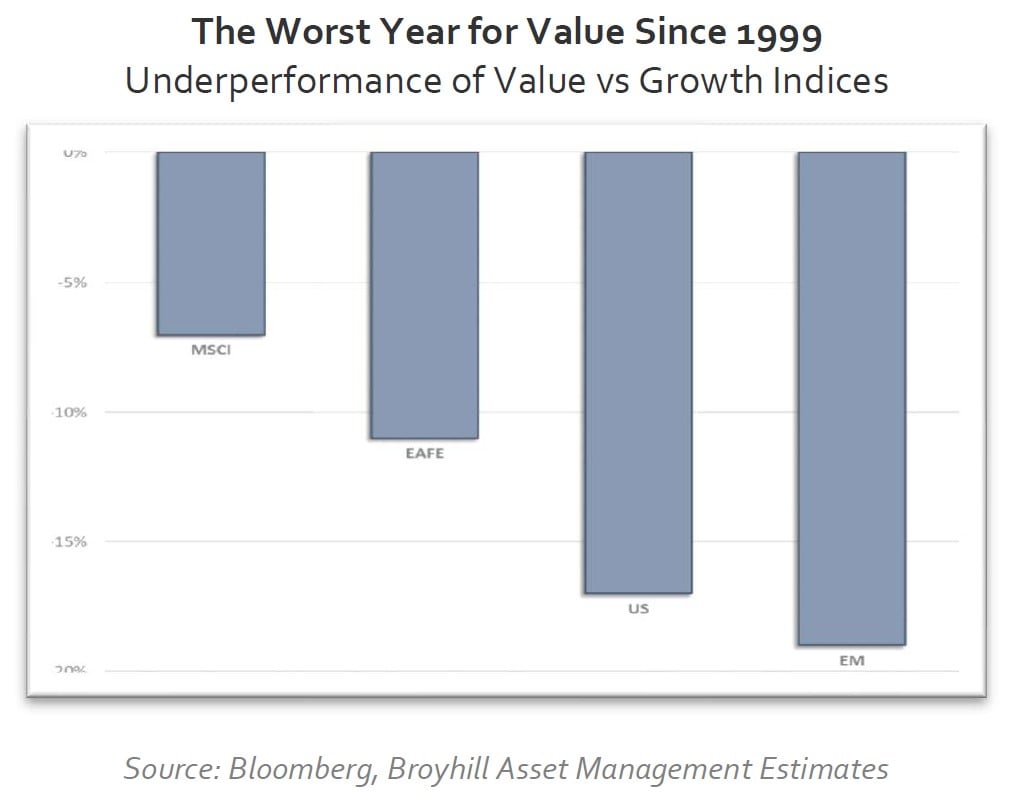

Value stocks underperformed growth stocks by 17% in the US last year—their worst calendar-year performance since 1999. It was a painful year for value investors.

You’d think we’d have gotten used to it by now, since value has been out of favor for the past five years. If we were a country, some might even refer to us as a shithole. Except that value underperformed everywhere else around the world as well (chart below). In emerging markets, for example, the gap was closer to 20%.

The market was expensive last year. And the year before. And the year before that. One could argue that valuation no longer matters.

The relationship between price and value can be greatly distorted by psychological and technical factors in the short term. Distortions can even continue for years. But not forever. Eventually, that last buyer throws in the towel, and momentum is exhausted.

The surge of retail activity in the markets is a late cycle indicator. 4 It's something we see at market tops. Not bottoms.

Old Economy Steven

Even as the broader market was setting record highs day after day, certain segments were completely ignored. Others were left for dead. In a similar fashion to the last great tech bubble, the decline of "old economy" stocks has accelerated as competitors with seemingly endless pockets challenge incumbents.

We've examined these competitors for years. In hindsight, we’d have been a lot better off just buying them, rather than worrying about who they might disrupt and how. But I don't think that is the case today. In fact, in many cases, I think the incumbents represent a better bet than the disruptors.

Disruption is not new to capitalism. There's always a new, new thing.

Yet, businesses that have been built over generations on solid foundations usually have at least a few good reasons to be around as long as they have.

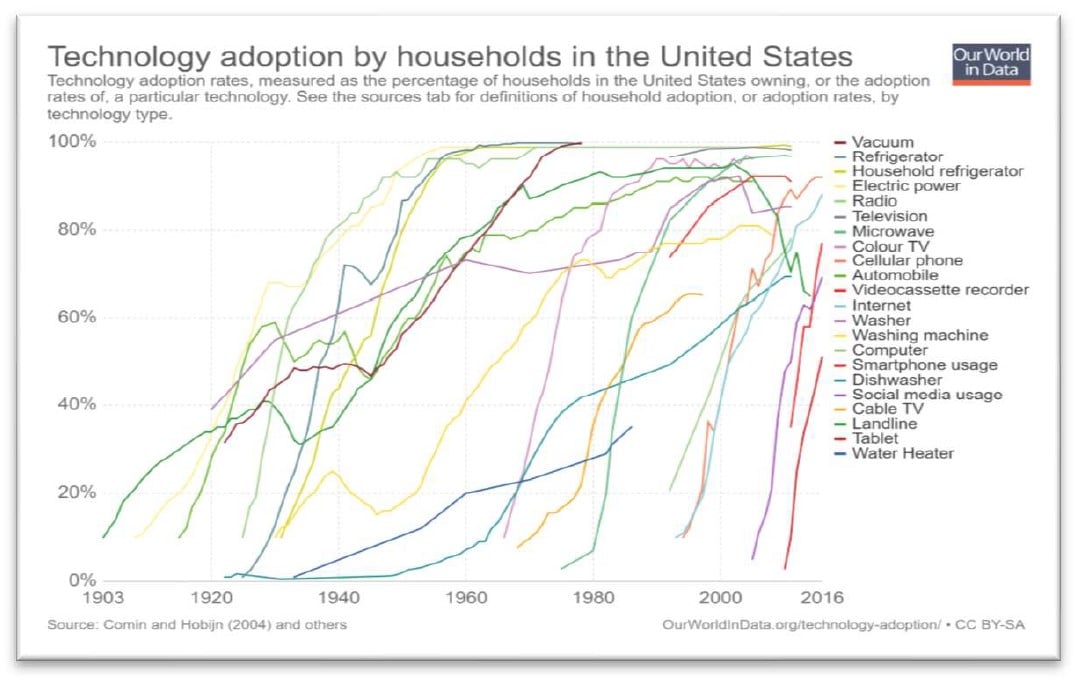

The horse and buggy were disrupted by the automobile long ago. Radio was disrupted by television. Newspapers (and just about everything else) by the internet. The capital cycle has always ensured that high returns are competed away. But this is happening at a much faster pace today than at any time in history.

While it took the telephone a century to reach a saturation point in households, the tablet computer went from nearly 0% to 50% adoption in about five years.

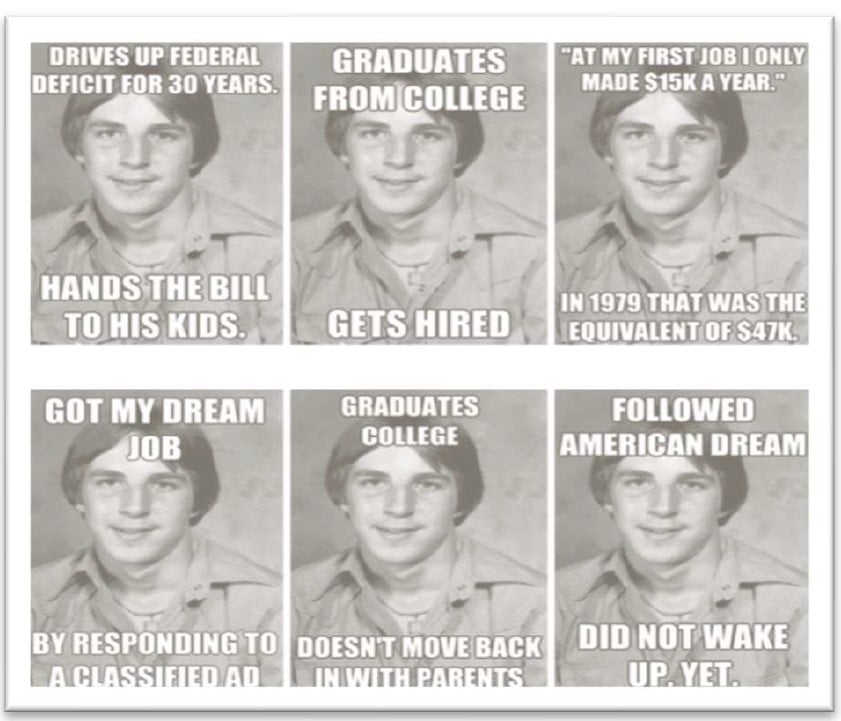

Rapid changes in our economy have been neatly captured by the often-perceptive and always-snarky “meme” creators who dominate and delight social media.

To capture the differences between “then” and “now”—between “old” and “new—an avatar emerged about five years ago, known as Old Economy Steve.

Old Economy Steve is represented by a relatively generic and affable 1970s yearbook photo of your run- of-the-mill, Camaro-driving dude. But Old Economy Steve is framed by a seemingly endless series of “burns” through captions that highlight the relative prosperity and security that Old Economy Steve could look forward to, versus the much less stable and much more precarious future that today’s millennials, and incumbents, face.

No one question the assumptions underlying today’s “new economy.” And it is precisely this consensus sentiment what creates opportunity for brave, contrarian investors. When you’re home for the holidays and mom asks you about Zuckerberg’s video strategy, then popular sentiment is getting extreme. When Grandma’s worried about Amazon disrupting the cozy, cross-cable knit blanket market, it’s time to fade the hype.

Sentiment can change. It wasn't that long ago that people literally laughed at us when we pitched Microsoft as our best idea. At the time, the stock was trading at a single-digit multiple net of cash. Today, the same company trades for nearly 30x earnings.

Old dogs rarely get credit for learning new tricks.

But young dogs rarely believe that they may even stumble.

We have no interest in shorting Bezos, Zuckerberg, or Page. Facebook and Google at mid-twenty multiples are not Cisco at 150x. But certain "dinosaurs" trading at double-digit free cash flow yields may offer a better risk/reward tradeoff today than the Nadella. Disruption may be accelerating. But human nature and investor psychology have not changed in centuries.

We cannot recall a time in recent memory when dichotomies were as wide as they are today.

At one extreme, there is a narrow group of businesses poised to take over the world. And at the other, there are ice cubes relaxing in a sauna.

Yet, when purchased at the right price, even a melting ice cube can offer a refreshing return, as one of our investors in the envelope business (USPS is not exactly a growth industry) has demonstrated. The liquidation of peers, acquisitions that consolidate market share, and cost cuts often leave the last man standing with quite a nice stream of recurring cash flow.

Competition is not new.

It may be fiercer today than ever. It may happen faster.

It may seem like it's more unpredictable. But it has never been predictable.

We will never know with certainty how incumbents may be disrupted. Where the threats will come from. Or how fast those threats will emerge. But we can attempt to tilt the odds in our favor when valuations already imply these businesses are dead. In doing this, we can minimize the pain of being wrong and maximize our profits if things turn out a little less badly than everyone expects.

Get A Good Ball to Hit

In a year where every sale was too early and every pass was a missed opportunity, it was very easy to get frustrated. It was even easier to relax your standards and settle. Capitulation is the easy way out. It’s also foolish. And completely irresponsible as a trusted steward of capital.

Most investors have probably heard about the mythical “sweet spot” at least a few dozen times by now. Buffett first referred to Ted Williams’s sweet spot in his 1997 letter:

We try to exert a Ted Williams kind of discipline. In his book The Science of Hitting, Ted explains that he carved the strike zone into 77 cells, each the size of a baseball. Swinging only at balls in his ‘best’ cell, he knew, would allow him to bat .400; reaching for balls in his ‘worst’ spot, the low outside corner of the strike zone, would reduce him to .230. In other words, waiting for the fat pitch would mean a trip to the Hall of Fame; swinging indiscriminately would mean a ticket to the minors.

If they are in the strike zone at all, the business ‘pitches’ we now see are just catching the lower outside corner. If we swing, we will be locked into low returns. But if we let all of today's balls go by, there can be no assurance that the next ones we see will be more to our liking. Perhaps the attractive prices of the past were the aberrations, not the full prices of today. Unlike Ted, we can't be called out if we resist three pitches that are barely in the strike zone; nevertheless, just standing there, day after day, with my bat on my shoulder is not my idea of fun.

Ted Williams was lucky to get an important piece of advice from Rogers Hornsby early in his career. Hornsby’s advice was simple: “The single most important thing for a hitter is to get a good ball to hit.”

One would think this would be incredibly obvious. It’s completely intuitive. Yet it’s incredibly difficult in practice.

As Williams said, “Everybody knows how to hit. But very few really do.”

To understand why, we need to consider human psychology. Until you’re standing at the plate in the big game, it’s impossible to know how frustrating it is to watch good pitches blow by you.

It’s extremely hard to hold back on pitches you know you can hit. Sometimes a high ball over the strike zone can be hit hard if it’s in tight. In a year like last, most of these balls were hit out of the park. It’s no fun taking called strikes or even a base on balls when everyone around you is swinging for the fences.

Last year, a lot of mediocre balls were hit into the stands. But more often than not, when you swing at a mediocre pitch, you get a mediocre result.

Occasionally, you can turn a decent pitch into a blooper for a base hit, but most of the time, nothing happens. Worse, you can get into real trouble when you start fishing for pitches outside your sweet spot. You might start with something that’s an inch off the plate. On a good day, you might be able to drive that ball into the gap. But, then, at your next at bat, you take a stab at something two inches off. Then three. And, before you know it, you’re striking out on pitches you had no business swinging at in the first place!

Standing there, with a bat on your shoulder, day after day, is not fun. It’s downright torture when you’re playing in a little league park and hitting on the equivalent of a tee-ball stand.

We got a few pitches in our sweet spot early last year. And we took good-sized swings when we saw them. But last year, every pitch could have been hit out of the park, and in comparison, we just didn't swing enough.

We passed on several mediocre balls that weren't in our sweet spot. As it turns out, we could have put more runs on the board if we took a cut at a few more pitches over the plate. Instead, we took more than our share of called strikes. We watched as a few of them were launched over the left field fence later in the game. We’ve spent a good bit of time reflecting on those.

We are always looking for opportunities to improve our process. To learn from our mistakes. Should we have swung a little faster? Couldn’t we have at least driven that ball past the infield? Were we on top of the count? Did we watch enough tape?

But it’s equally important to resist jumping to conclusions, particularly when studying a small sample size.

A bull market hides many mistakes. Those who take the biggest swings drive in the most runs. But those big swingers also tend to strike out a lot.

Those who wait for a good ball to hit risk severe boredom standing at the plate. But we’d rather be bored than strike out on pitches we had no business swinging at. Particularly when this game is already well into extra innings.

A good hitter can hit a pitch that is over the plate three times better than a great hitter with a questionable ball in a tough spot. But the greatest hitter living can’t hit bad balls good.

Bottom Line

With so much capital invested without any consideration for fundamentals (index investors) or completely on short-term auto pilot (program traders), this is a wonderful time to be a long-term value investor.

Bargains are out there, and we are working diligently to find them, but with increasing complacency in the markets, they are rarely hiding in plain sight. So, we keep looking. In the interim, don't confuse a lack of trading activity with a lack of effort. Your “quiet” monthly statements do not represent a dearth of ideas or flagging enthusiasm. The trades you will see tomorrow are a product of our tireless efforts today.

We are not sitting on the bench, picking our noses and scratching our bottoms. We are observing the game carefully. Looking for patterns. Watching for every opening. As Ted Williams said, “The observant guy will get the edge.” We are revisiting and testing our assumptions on a regular basis so that we can be quick with the bat when we see a good ball to hit. We’ve learned, over time, where are happy zones are.

Do not underestimate the importance your trust and confidence play in navigating this increasingly challenging environment. Without it, we would not be able to do what we do.

As always, please feel free to reach out to us any time with questions. We are exceptionally fortunate to have such a great group of long-term investors who place their trust in us. We come in to the office each day striving to earn it.

Sincerely,

Postscript

In typical fashion, Charlie Munger has condensed this philosophy into brilliantly simple advice: “Look at lots of deals and don’t do almost all of them.” Wise investors bet heavily when given the opportunity. They bet big when they have the odds. And the rest of the time, they do nothing—because doing nothing puts you in a great position to do something in the future.

Subsequent to year end, Mr. Market gave us a brief window to do something. We saw more good pitches in February than we’ve seen for some time. So, we took some swings that we’ve been patiently waiting on, and we look forward to discussing these businesses with you in our mid-year letter.

See the full PDF below.