An international team of researchers has discovered that it is, indeed, possible to bend diamonds – successfully stretching the hardest natural material on Earth.

Diamonds are well-regarded for their long-lasting hardness, finding applications both in expensive jewelry and in industrial applications where the strength of the material is paramount. It was thought for quite some time that it was impossible to bend diamonds, but a team of international researchers made up of scientists from MIT, Hong Kong, Singapore, and Korea have found that when grown in extremely tiny shapes, Diamond can stretch – much like rubber – and snap back to its original shape.

This finding is surprising, and goes against what we had thought to be true. The research is being published in the journal Science by senior author Ming Da, a principal research scientist in MIT’s Department of Materials Science and Engineering; MIT postdoc Daniel Bernoulli; senior author Subra Suresh, the former MIT dean of engineering and president of Singapore’s Nanyang Technological University; graduate students Amit Banerjee and Hongti Zhang at the City University of Hong Kong; and various professionals from CUHK and institutions in Ulsan, South Korea. The list of authors is long, but the results are incredibly small in size – experimenting on extremely tiny slivers in a needle-like shape to determine that it’s possible to bend diamonds.

While the finding that we can bend diamonds is significant in and of itself, it may also open the door to a variety of diamond-based devices – with potential applications in the fields of data storage, actuation, biocompatible in vivo imaging, sensing, optoelectronics, and even drug delivery. With recent explorations suggesting that diamonds could be a possible biocompatible carrier for delivering medicine to cancer cells, the discovering that we can bend diamonds may further advance research in a variety of medical and technological fields.

In the published paper, the team demonstrated that the narrow needle diamonds could flex and stretch by as much as 9 percent without breaking – bouncing back to their original configuration shortly afterwards. With ordinary diamonds stretching as little as 1 percent, it appears that a size of just a few hundred nanometers makes it much more possible to bend diamonds.

“It was very surprising to see the amount of elastic deformation the nanoscale diamond could sustain,” said Bernoulli.

“We developed a unique nanomechanical approach to precisely control and quantify the ultralarge elastic strain distributed in the nanodiamond samples,” says Yang Lu, senior co-author and associate professor of mechanical and biomedical engineering at CUHK.

When crystalline materials such as diamond are put under elastic strains, it’s possible to change their mechanical properties as well as thermal, optical, magnetic, electronic, and chemical reaction properties in significant ways. These new findings could open up a world of possibilities and new applications now that we can bend diamonds. It’s also possible that this technology could be applied to other materials, making the process of bending diamonds a building block for further scientific advancement in other fields.

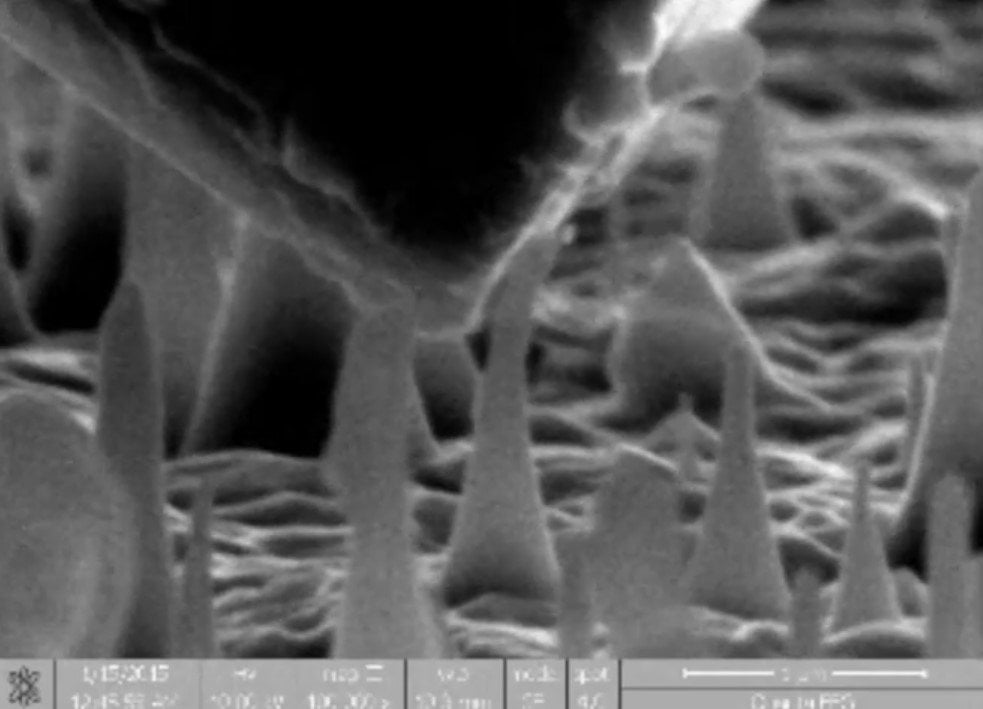

During the experiment, the team measured the ability to bend diamonds that were grown through a chemical vapor deposition process and then carefully etched into their final shapes. These materials were observed by a scanning electron microscope while pressing down on the needles with a standard nanoindenter diamond tip. After observing through the microscope, the team ran a number of detailed simulations that were able to determine just how much we were able to bend diamonds – research which came up with the 9% figure.

It remains to be seen the exact applications that the ability to bend diamonds will be used in, but it’s an exciting development and new information about the hardest material on Earth – one that may be much more flexible in certain situations than you’d think.

The project was funded by the Research Grants Council of the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region, Singapore-MIT Alliance for Research and Technology (SMART), Nanyang Technological University Singapore, and the National Natural Science Foundation of China and is published in the journal Science.