RV Capital commentary for the year ended December 31, 2021, dicussing their new investment in Carvana Co (NYSE:CVNA).

Q4 2021 hedge fund letters, conferences and more

Dear Co-Investors,

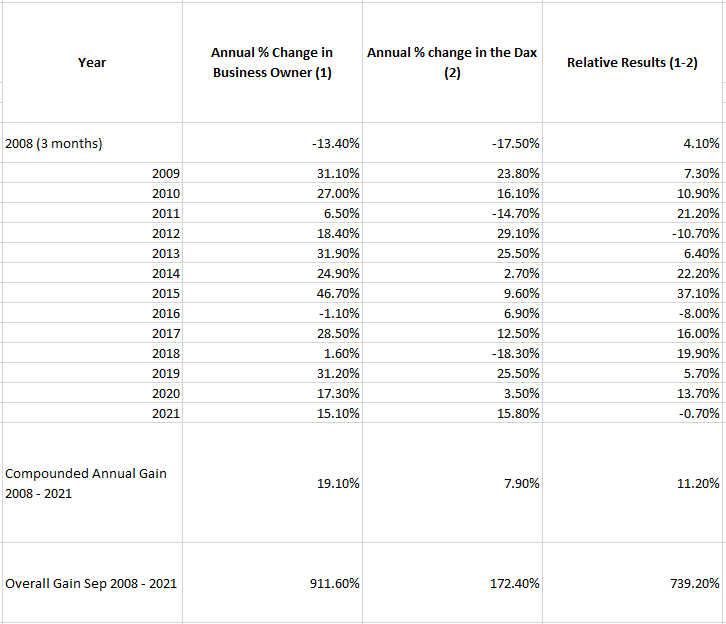

The NAV of the Business Owner Fund was €1'003.77 as of 30 December 2021. The NAV increased 15.1% since the start of the year and 911.6% since inception on 30 September 2008. The compound annual growth rate since inception is 19.1%.

Part I: A New Investment

I wrote in my first half letter of 2020 that I was keen to invest more in what I termed "early-stage growth companies". I am happy to report that I was able to take advantage of the current pessimism surrounding fast-growing companies and have added one new investment to the portfolio: online used car retailer, Carvana.

I was first introduced to Carvana in 2018 by my friend and fellow investor Cliff Sosin of Cas Investment Partners. I am grateful to him for telling me about the company and helping me build up an understanding of it.

About Carvana

Carvana is the largest e-commerce platform for buying and selling used cars in the US. It was co-founded in 2013 by CEO and major shareholder Ernie Garcia, III. In 2021, it likely sold over 400’000 cars at retail. For context, total used car sales in the US hover around 40 million units p.a. With a 1% market share, Carvana has a small share of an enormous market.

Improving the customer experience

Carvana’s purpose is to provide a better value proposition to consumers along the three vectors that matter most to them: value, selection, and customer experience. It aims to offer a wider selection, a more attractive price and quality, and a simple, haggle-free transaction.

To achieve this, Carvana has built out its own infrastructure across the entire used vehicle value chain. It has an easy-to-use website on which customers can buy or sell their car, obtain financing, and purchase other ancillary products such as vehicle service contracts or GAP insurance. It has developed a patented photobooth technology allowing customers to do a virtual tour of a car prior to purchase. It has built inspection and reconditioning centres (“IRCs”) for preparing vehicles for sale. It has an in-house logistics network for delivering vehicles to the customer’s doorstep or one of its innovative vending machines as well as picking vehicles up in the case of a trade-in or stand-alone sale. It has developed a proprietary algorithm for efficiently purchasing used cars from customers or at auction without seeing the vehicle in person before giving a firm bid. And it has developed an in-house lending business for underwriting loans across the whole credit spectrum.

Carvana is the only player attempting to vertically integrate into all parts of the value chain. Its web-based competitors mostly do not do this. Instead, they aggregate dealers’ as well as private sellers’ inventory on a website. Whilst customers can browse vehicles online, the transaction is otherwise no different to how it was twenty years ago. It relies on legacy infrastructure built mostly around the physical dealership model. It does not fundamentally change industry cost structures or the customer experience.

A better way

Through its vertical integration, Carvana can offer a vastly superior customer experience. It is better value. Carvana estimates that it can sell vehicles up to $1’000 cheaper than its competitors by replacing the expensive dealership model with a self-service website and its in-house logistics network as well as realizing efficiencies in other areas such as reconditioning. It is faster. Carvana can deliver the next day in some markets. And there is a wider selection. At the end of the most recent quarter, Carvana had around 56’000 cars available for sale on its website compared to up to 250 at a traditional dealership and 15’000 across all dealerships in a local market.

Why are we invested in Carvana?

Whenever I evaluate a business, the place I start is with the people. In Ernie Garcia, we are partnering with someone who combines a deep love of the business with mastery of automotive retail. In 2018, he gifted part of his stock holdings to all employees with more than one year tenure. And during the first Covid lockdown, senior executives including Ernie paid their salaries into a fund to support staff on reduced hours. He clearly cares deeply about the business and his associates.

Mastery comes from deep domain expertise. As the son of the founder of DriveTime, a large subprime auto dealer and lender, he grew up around the used car business and has led Carvana’s development since day one. What comes through when I hear Ernie speak is someone who relishes the challenge of reinventing the way that cars are sold and enjoys solving each problem that crops up along the way. He is one of a handful of founders, including Amazon’s Jeff Bezos and Shopify’s Tobi Lütke, that I never tire of hearing speak.

It is rare to find a CEO who both deeply cares about a business and is uniquely placed to lead it. It does not seem too much of a stretch to imagine that Carvana is his life’s work. This is exactly what I look for.

An Emerging Moat

After people, the next criterion for an investment is a wide and, most importantly, growing competitive advantage or moat. Carvana has three main sources of competitive advantage: scale, brand, and culture.

Scale

Carvana’s growing scale provides it with several advantages. Carvana can carry more inventory providing customers with a broader selection. It can operate a denser logistics network which means shorter distances to the average customer, better network utilization, and faster delivery. And it can gather more data to optimize each part of the business. The great thing about scale is that the more the company grows, the more pronounced these advantages become, allowing it to grow still faster in a virtuous circle.

Brand

Carvana's brand is also an important source of competitive advantage. The traditional used car buying experience is slow, unpleasant, and expensive for consumers. Carvana has reworked the entire value chain to provide the customer with an objectively superior customer experience. This makes its brand very valuable given that the purchase (or sale) of a car is a big-ticket item for which trust plays a crucial role. Here too, I expect Carvana’s brand value to grow over time as more people use the platform and word spreads.

Culture

Carvana's culture is the final source of competitive advantage. Carvana is a company that is built to tackle a hard problem – how to sell cars online. There are multiple facets to solving this – scaling inventory, building IRC capacity, expanding the logistics network, investing in advertising, and so on. Furthermore, each part must be scaled fast enough that it does not cause a bottleneck further down the line but not so fast that there is too big a mismatch between supply and demand. It is a multivariate problem with multiple feedback loops. The upshot is a company that seeks out big problems and attracts great employees that enjoy solving big problems. Here too, there is a virtuous feedback loop that should magnify Carvana’s competitive advantage over time.

An attractive price

Ultimately, no matter how good a business is, it only makes sense as an investment if it can be bought for less than it is worth. This means estimating its long-term cash-generating ability, discounting it to the present to arrive at an intrinsic value and comparing that value to the current price. Please note: although the output of this exercise is necessarily quantitative, the input is mainly qualitative. What drives the valuation is the qualitative belief that a combination of people, competitive advantages and market opportunity will lead to a large and flourishing business. The ultimate size of the business will likely differ from expectations, but if the qualitative analysis is proven out, it should be directionally correct. With this in mind, what are my main valuation assumptions?

2 million cars per year

Carvana's immediate target is to sell more than 2 million used cars at retail p.a. This seems realistic given its market penetration in older markets and the fact that they continue to grow rapidly. At 2 million cars, it would account for roughly 5% of the US market. The main bottleneck to achieving this is supply rather than demand given the superiority of its value proposition. It should have IRC capacity in place by 2024 to recondition 2 million units p.a. If it takes a few years to ramp this capacity, Carvana should be in reach of its goal within five years or so.

$30K revenue per retail transaction

When it sells 2 million cars, I assume total revenue per retail transaction of $30K. This figure includes income from wholesale, financing and ancillary products and assumes modest annual inflation from pre-pandemic price levels. This equates to revenue of $60bn p.a.

8% net income margin

The company targets an EBITDA margin range of 8-13.5%. At first blush, this seems high given that Carvana is only just profitable at the EBITDA level today despite already having around $13bn in revenue. What this hides though is that Carvana invests in every aspect of the business well ahead of time to minimize any future bottlenecks to growth. It builds IRCs years before it will likely need them, advertises in markets where it is not yet present and invests heavily in its logistics network as well as building new products and capabilities. The focus is on getting to scale as quickly as possible, not maximizing today’s profits. Despite these investments, in its older markets, Carvana is already close to the lower end of its EBITDA margin range today.

At a 12% EBITDA margin, towards the high end of the range, Carvana would generate EBITDA of around $7.2bn p.a. After, depreciation, interest and taxes, this equates to $4.8bn in net income, equivalent to an 8% net margin.

$96 bn fair value

A multiplier of 20x implies an intrinsic value of $96bn compared to a market value today of around $25 bn .

In practice, Carvana will likely still be re-investing into the business. As such, reported EBITDA will likely be lower than $7.2bn in five years. Given that at 2 million cars, its market share would still be just 5%, this makes sense in my view. The point of the margin assumption is to get a sense of the underlying cash-generating ability of the business.

Accurate, not conservative

In the past, I have discussed that it is preferable to be accurate than conservative when valuing companies. A conservative valuation would most likely stop five years out. An accurate valuation would attempt to quantify the long-term opportunity (in full cognizance that the outcome is likely to be very different from the forecast). In this spirit, what does the long term look like?

Growing internet penetration

I expect the Internet to continue to take share from in-store, as has already happened in many other retail markets. The value proposition is simply better. For most people, it does not make sense not to buy a used car over the Internet.

Winner takes most

Within automotive e-commerce, the leading player should benefit from a winner-takes-most dynamic. What drives this is multiple positive feedback loops. More sales drive greater inventory selection which drives more sales. More sales drive a denser logistics network and shorter delivery times which drive more sales. And more sales drive better coverage of fixed costs and lower prices which drive more sales. As such, it seems likely that Carvana’s ultimate market share is far greater than 5%.

A gravitational pull towards market concentration

A market share of 5% or higher seems plausible compared to other retail verticals where the leader may have up to 50% of the market. One counterargument is that the automotive retail market has historically been highly fragmented. CarMax, Inc (NYSE:KMX), the largest used car dealer in the US, has around 2.5% market share nationwide after almost 30 years of operation (whereby its market shares in more mature local markets are higher). I firmly believe though that the market structure of physical dealerships provides little indication of what the end state of the online market looks like. Few aspects of a physical dealership scale. The inventory, physical infrastructure and staff must all be replicated at each individual site. At the same time, physical dealerships tend to find that inefficiency and fraud increase when they expand beyond one site as the owner cannot be present everywhere at once. By contrast, virtually every aspect of Carvana’s business model scales. If there is a strong gravitational pull towards fragmentation in the offline world, it pulls in the opposite direction online.

Additional revenue opportunities

Gains in market share are not the only source of upside in the long term. The business will add additional revenue streams over time. It is experimenting with adding a marketplace for 3rd party vehicles on its platform. It has initiated a partnership with Root to offer car insurance. And private label is also likely to play an important role in automotive retail as in other retail categories. Given its strong brand equity, Carvana would be a natural partner for a no-name Chinese manufacturer of electric vehicles.

Surprises

In my experience, the surprises in great companies tend to be to the upside. If my qualitative analysis is correct, I am optimistic this will be the case at Carvana too. I am looking forward to seeing how this plays out as a co-owner in the coming years.

Part II: Moat vs. Execution

Ben Graham famously said:

Investment is most intelligent when it is most business-like.

The quote resonated so strongly with me that it is part of the reason why I called my fund “Business Owner”. I take it to mean that there is an opportunity for outperformance where standard investing practice diverges from what a businessperson would do. Accordingly, I am always on the lookout for areas where this is the case.

The importance of people

One such area, as I have discussed before, is people. Entrepreneurs place far more importance on people than investors do. I have never met an entrepreneur who does not believe that the success of any commercial venture is mainly down to the people running it. Investors, on the other hand, rarely base their investment case on people and sometimes skip the topic altogether. This is why “people” is my first investment criterion (though not the sole one). It is partly because it is important, but also because it is more likely to be a source of market inefficiency to the extent other investors are paying less attention to it.

The importance of execution

Another area where I suspect there is a gap between entrepreneurs and public equity investors is the importance they place on execution. It is this topic I want to dedicate the rest of this letter to.

Entrepreneurs view execution as absolutely central. Venture capitalist John Doerr sums the view up succinctly:

Execution is everything.

Investors, by contrast, tend to view execution as of subordinate importance to competitive advantage. Harvard economist Michael Porter was the first advocate for the centrality of competitive advantage and wrote two books on the topic. He describes operational effectiveness as a necessary but not sufficient condition for success. It is a view espoused most famously by Warren Buffett, no doubt informed by his early travails with a failing textile mill called Berkshire Hathaway. He sums up his view as follows:

I try to invest in businesses that are so wonderful that an idiot can run them. Because sooner or later, one will.

Execution is everything

I have never felt comfortable with the idea that operational excellence is less important than a competitive advantage as it is at odds with my direct investment experience. The best companies I come across differentiate themselves by making small incremental improvements to their business every day as opposed to being insulated from competition through a moat.

The first company that opened my eyes to this point is Bechtle AG (ETR:BC8), a German IT Services company. In a fragmented and highly competitive market, it has outperformed its competitors for decades by simply doing every part of the business better than everyone else.

Other investments reinforced this view, including Trupanion Inc (NASDAQ:TRUP), the pet health insurance company and Credit Acceptance, the subprime auto lender. Trupanion is permanently trying to get better at the details of the business such as forecasting loss rates, increasing customer retention, and deploying more capital into customer acquisition. CEO Darryl Rawlings discusses the company's progress in these and other areas in his excellent investor letters. Credit Acceptance practises what it terms "organisational hygiene". Every month, the leadership team canvasses employees on the biggest bottlenecks to them doing their jobs better, then works on removing them. The following month it repeats the same exercise all over again. There are many more examples I could give.

Moat is an output

As these companies have grown, they have gained scale, harvested more data and enhanced their reputations. The result is multiple competitive advantages such as economies of scale, strong brands, and data network effects. However, these competitive advantages are the trappings of success, not the cause. It is like observing a successful businessperson who drives a Ferrari and arguing that they are successful because they own a Ferrari.

Does the importance of execution wane over time?

Of course, the argument could be made that operational excellence is most important in the earlier stages of a market. Once the competitive structure has formed into a steady-state, execution diminishes in importance, and the benefits of a strong competitive advantage come to the fore. The validity of this argument depends though on how stable a sector’s competitive structure is expected to be over time. If the assumption is that a sector’s structure is basically fixed, and there is no prospect of change through technological or business model innovations, then having a competitive advantage probably is of paramount importance. However, how frequently is that the case today? Most sectors are in a state of flux. As such, it is far better to be permanently working on getting a little bit better every day rather than relying on a competitive advantage derived from past glories.

Is competitive advantage even a handicap?

The argument could be made that too strong a competitive advantage is even detrimental when a market is in flux. Which company is more likely to fight every day to meet customers’ constantly changing and expanding demands – one which believes it has a birthright to outsized profits or one which understands that the customer’s trust needs to be won afresh each day? Clearly the latter.

The tension between competitive advantage and operational effectiveness

Michael Porter would likely argue that a company should aim for both operational effectiveness and competitive advantage. In practice, I imagine most companies do. To the extent they make economic profits, they either have a sufficiently wide moat to offset their operational ineffectiveness, sufficient operational effectiveness to offset the lack of moat or a combination of the two. What this reveals is a fundamental conflict of interest between the two ideas - one reduces the need for the other. It is like giving your child a large trust fund and hoping they grow up ambitious. They may do, but the trust fund probably does not help. Ideally, one would wish for a guiding principle that pulls a company towards both a widening moat and ever-greater efficiency.

Tackling hard problems

Tackling hard problems or complexity is a candidate for such a guiding principle. It requires a singular focus on execution. Moreover, the harder the problem to be solved, the wider the moat will likely be. As a guiding principle, it resolves the tension between moat and execution in a way that a singular focus on building competitive advantage does not.

Ernie Garcia makes precisely this point in a podcast with Patrick O’Shaughnessy:

I think complexity is to me a really good property if you're trying to build something really big, but it's also a property that decreases your odds of success. Complexity generates a higher likelihood of failure, but it also generates, in my opinion, the most important and persistent and durable moat once you clear it. So I think to me, complexity is a function of how big a swing you want to take to some degree, but maybe that's how I think about that.

Garcia goes on to illustrate his point using the example of electronically registering cars online, which appears to be a tough problem to solve as the DMV's systems are fragmented and archaic. It is an important one though as otherwise, a transaction cannot be fully online:

But the truth is every problem is interesting. Just to dive into one, finding a way to title cars effectively and register cars effectively across 50 states with DMVs in every state that have different processes, and you're interacting with a customer who's entering information into a fixed interface, and then ultimately it's got to go to the DMV who's going to interact with it manually. There's nothing on the surface sexy about that problem, there's not a single thing. But it's incredibly interesting when you dive in. And I think that's another really important thing in trying to be successful, is when you find these complexities, can you find great people that want to tackle superficially sexy problems? And can you get those people to be like, "Hey, but wait a minute, this other problem that has no sex appeal whatsoever is actually even cooler because it's got the same complexity as the sexy problem, but no one's tackling it because it's not sexy and we can make an even bigger impact here?" And I think that's really, really important too as a way to manage that complexity, is just to try to generate inside of a company inside of a culture, appreciation and excitement around solving hard things regardless of where those hard things are.

What this example demonstrates is the centrality of execution. Yes, to the extent the company were to solve the problem of digital registration, it would have a moat - smaller companies presumably cannot afford to program an electronic interface to 50 DMVs - but this overstates the importance of the moat. Any moat is a byproduct of great execution. It is the output of success, not an input. Furthermore, to the extent that Carvana is successful going forward (and by extension any other company in a rapidly developing market), it will not be because of a legacy competitive advantage, in this example from digital title registration. It will be because it tackles all the other hard problems that need to be solved to sell cars online.

The symbiotic relationship between hard problems and execution

What this example also demonstrates is the symbiotic relationship between hard problems and execution. As Ernie Garcia says, hard problems attract ambitious people. The very act of tackling hard problems increases the chances of solving them as they attract the best people. This allows a company to tackle still harder problems that pull in yet more great people in a virtuous circle.

Returning to Berkshire Hathaway's failed textile operations

The lens of "solving hard problems" suggests an alternative explanation for the failure of Berkshire Hathaway Inc. (NYSE:BRK.A) (NYSE:BRK.B)’s textile operations. Warren Buffett has said that no amount of execution could have saved them because they simply did not have a moat. His analysis is likely correct but perhaps incomplete. Is it not also possible that execution was useless because of the absence of sufficient complexity for it to make a difference? Maybe, there were just not enough hard problems in a 1950s textile factory left to solve.

The importance of hard problems

The implication is that it is not enough simply to have a moat. Companies must also have plenty of hard problems left to solve. Only then can they continue to attract ambitious people. Only then are they forced to improve their execution every day. And only then can they widen their moat further. A company that has solved the customer’s problem is a sitting duck in the crosshairs of the next technological innovation irrespective of how wide its moat is today.

RV Capital's 2022 Annual Gathering: Take Two

RV Capital's 2022 annual gathering was originally scheduled for late January. Unfortunately, it had to be postponed due to the increasing prevalence of the Omicron variant in Switzerland and elsewhere. The new dates are 26-27 March 2022. Registration will open on 28 February 2022. I realise that this is quite short notice, but I hope by then there will be more visibility on whether the event can take place and whether people can get there. Fingers crossed, we have more luck on the second attempt!

I look forward to seeing as many of you as possible then.

In the meantime, all the best,

Rob