ValueWalk’s interview with Tony Wenzel, the co-founder and President of Brandometry® LLC. In this interview, Tony discusses his and his firm’s background, the Brand Value ETF, different types of intangible assets, balance sheet valuation, identifying strong but undervalued brands, the 50 stocks they own, standardizing how intangible assets and brand value are classified and measured, calculating the worth of intangibles, book value is outdated, and making accounting standards more transparent.

Can you tell us about your background?

I have a passion for getting ahead of trends and leveraging the business opportunity they present. That’s how I got interested in brand economics and investment indexes. I have an undergrad degree in business and an MBA with a focus on finance, so finance has always been a strong interest, along with disruptive ideas that can transform industries.

Q2 hedge fund letters, conference, scoops etc

What about your firm?

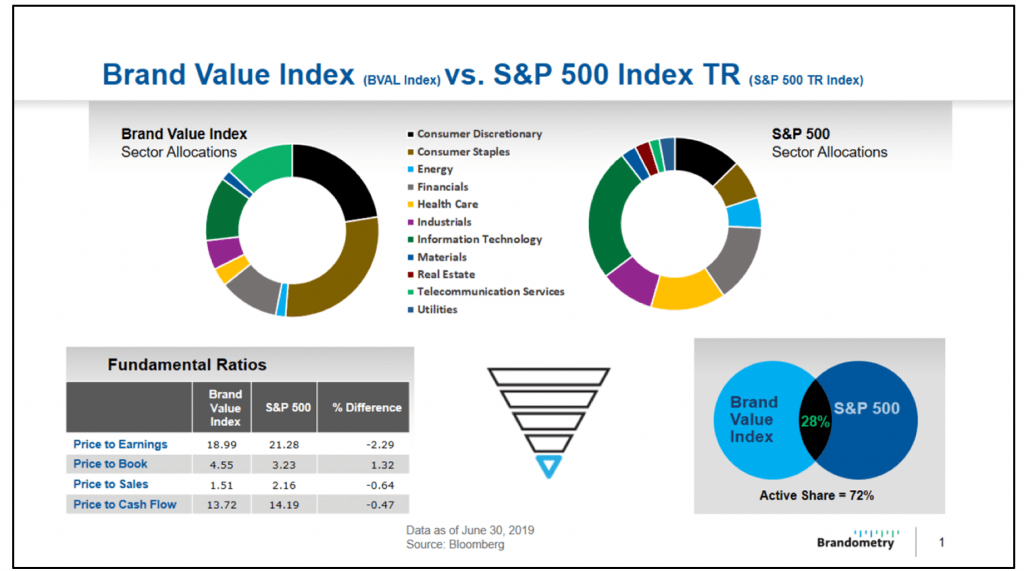

We founded Brandometry as an index provider with the goal of providing a platform for products built around intangible assets—including brand—which for many companies is the largest component of their market value. Our first effort along those lines is the Brand Value Index (.BVAL). It is a core, thematic index that uses brand signals to identify strong brands that are undervalued. All constituents are US large and mega-cap equities and household names held in equal weight and rebalanced every September.

What about your ETF? It measures intangible assets and brand value?

Hedge funds were among the first firms to use non-traditional signals to create exposures. We’ve brought that thinking to ETFs with BVAL, which utilizes its index’s qualitative signals about brand power to identify companies with strong brands. It appears to be working: the Brand Value ETF has outperformed the S&P 500 (as of 9/24/2019, one year performance was 5.25 vs. 4.48) with lower volatility, greater dividend yield, and very strong ESG scores*.

The ETF’s index exemplifies value, growth, and quality characteristics. In fact, if you think of factors (market, value, momentum, quality, and size) as separate ideas rising from the x-axis, our index could be a line that intersects each factor horizontally from the y-axis.

What are intangible assets and brand value? Can you define the different types?

Intangible assets are created through intangible investment. Intangible assets lack physical substance—they can be used, but not necessarily seen or touched. Examples of intangible assets include software, design, partnerships, talent, copyrights, franchises, patents, trademarks, and trade names.

The tricky thing with intangibles is that they’re often created in secret to keep them safe from theft, so classifying them publicly poses risks. Most people forget how easy it is to steal an idea. By design, these assets are often hard for outsiders to identify.

How do you value the balance sheet of companies you find?

Intangibles represent most corporate value, yet they rarely show up on the balance sheet. So, to understand what part of a business is intangible, one must subtract book value from market value. If that sounds like “goodwill,” it is. Goodwill is the best neighborhood on the balance sheet these days.

Software is an extreme example. In 2006 Microsoft was the most valuable company in the world. It had a market capitalization of about $250 billion. Yet, the balance sheet showed a valuation of only $70 billion, and $60 billion of that was cash and equivalents. So where was the other 180 Billion in value? Plant, property, and equipment were only $3 billion, representing 4% of company assets and only $1% of Microsoft’s market value. The rest of the value lay in intangible assets like people, patents, know-how, and brand. Does book value tell you anything about Microsoft? Not directly.

How do you identify strong intangible assets and brand value?

The Brand Value Index looks at the ratio between market value and brand strength to identify strong but undervalued brands.

The selection funnel begins with proprietary brand signal data from CoreBrand® Analytics, a division of Tenet Partners. Since 1994, CoreBrand has surveyed 10,000 senior business leaders and highly educated individuals per year to calculate brand strength data on over 500 companies, including all of the S&P 500. They consider overall reputation, management strength, and the likely of investment by the survey respondent. They then apply their proprietary scoring model. The final BrandPower® scores run on a 100-point scale. Our universe originates there.

To be eligible for the index, firms must be US companies or ADRs with a market cap of over $1B, must have positive ROIC, and must earn a Core Brand BrandPower score of 60 or higher.

That covers strong brand selection. To determine whether a company is undervalued, we look at spreads in the ratio. We seek the disconnect between a strong brand power scores and low underlying stock price. Here’s how that works:

- We look at the year-to-year change in Brand Power score for the qualitative numerator in our calculation. Then we look at the year-over-year change in company share price to create our financial denominator.

- Then we normalize the volatility scale. Stock price movements are more volatile than Brand Power Score movements.

- Finally, we look for the best spreads in companies with strong brands whose share price has not yet been fully realized by the market.

What stocks does your ETF currently own?

We limit the index to the 50 eligible companies with the best spreads between brand strength and share price. In our research, we found the best results via annual rebalances affected in September. So, every September we have a different index with different sector representation.

You’ll see names like Alphabet, Amazon, American Airlines, Apple, AT&T, Bank of America, Bristol Meyers Squib, Campbells Soup, and Capital One (as of 9/12/2019).

Is it weighted towards tech giants like Amazon and Google?

No, although if the brands are strong and undervalued, they will show up. All the companies in the index are held in equal weight, at time of rebalance. That’s important because equal weighting limits our exposure to market-weighted risks. When the S&P 500 dropped in December of 2018 and again in June of 2019, our drop was less deep. Equal weight is also how we create a very high active ETF share.

Can you tell us about regulatory bodies worldwide (ISO, SEC) taking numerous steps in recent years to create standardized metrics for intangible assets? How has GAAP and IFRS changed in this regard?

There are several groups focused on standardizing how intangible assets and brand value are classified and measured. ISO 10668 looks at monetary brand valuation. The Marketing Accountability Standards Board is working to establish marketing measurement and accountability standards for improvement of performance and transparency. The Financial Accounting Standards Board (FASB) has been considering methods for improving transparency, too.

I think the prime motivations are business performance improvement and transparency. The rub is that intangible investments are made secretively to reduce spillover to other firms, so, companies may not want auditors digging into one’s R&D files. I think standardization for performance is possible, but requiring too much transparency can be dangerous for companies and nations.

What percentage are intangibles of balance sheets in the US and international?

The actual number varies depending on industry. Surveys have indicated that $20-25 trillion of the US economy resides in intangibles. In software, intangibles can represent as much as 99% of corporate value. In mining, intangibles represent more like 2%. Currently, it is estimated that about 87% of the S&P 500 is intangible.

The million-dollar question is: how does an investor evaluate how much intangible assets and brand value are worth?

The short answer is that intangibles are the most valuable assets in most companies. If you want to calculate that value, just take the market value of the company and subtract the book value. What’s left is the intangible value.

To be sure, considering intangibles requires a different lens, but the bigger questions are: what is that value comprised of? Patents? Brand? Distribution advantage? What are the unique advantages those intangibles deliver? What competitive moats do they produce? The unique characteristics of intangible assets deliver strong synergies with other intangibles. Intangibles can become exponentially more valuable or completely valueless very quickly, too.

Intangible assets keep rising as a percentage of the balance sheet. Does that make book value outdated? Is it possible to find stocks based on quantitative metrics anymore?

Book value only measures a small fraction of the overall value of most corporations. Book Value doesn’t have the “oomph” it once had but still makes sense in some industries. Manufacturers have lots of equipment. Uber and Airbnb do not. In the mining industry, most corporate value is tangible equipment, inventory, plants, and property, but there are some proprietary processes. The valuation multiples determining market value on tangible-asset intensive businesses are typically low. But what if a mining company creates a chemical process to turn lead into gold? The value of that idea would go stratospheric, and the company’s market value would rise with it.

If you were SEC chair or president, what one change would you make to accounting standards?

I’ve had contact with several bodies working on standards to make things more transparent, however, it’s very tricky row to hoe. It would be wonderful if investors had a deeper understanding of how intangible investments create intangible value and how to measure that value. Yet, because ideas are easily stolen, classifying them publicly could create business, trade secret, and national security risks. Moreover, you want to offset benefits to investors against other hazards they might trigger. For example, the risk that the government might want to tax intangible value. That would be catastrophic for ideation and value creation.

If I were going to make a change it would be to equalize incentives for investment in intangible assets to those in tangible asset business. For example, making loans for intangible investments tax deductible. You can deduct loans to build an equipment factory, but you cannot deduct loans to build a brand factory, and that’s silly. Managed properly, this type of capital incentive could increase intangible investment and hasten the velocity of innovation. In an idea-based global economy, improving the pace of innovation has economic, strategic, and political value.

Experts estimate that Chinese theft of intellectual property alone costs the US between $225 Billion and $600 Billion annually. Some of that is via espionage, although it’s important to keep in mind that companies doing business in China are often required to share their highest value assets simply to get access to the Chinese market. Recent events, including President Trump’s sanctions and the ban on Huawei networking products, demonstrate that the government is now taking IP theft more seriously. It’s never been easier to steal one’s way into global power. I’m not a protectionist, but this may be our best option to change Chinese behavior and protect American companies and investors.

Final thoughts

I would urge people to consider deeply how intangible investment, and particularly branded investment, generates intangible value.

Corporate results are lagging measures and companies discuss them publicly. Leading measures are the targets companies use to meet their objectives. These are seldom discussed outside of the organization, but they can be deduced by outsiders if you pay attention.

For example, you might see that Company XYZ has many job openings for data scientists and Python programmers, which could indicate a new AI project. Those clues allow you to consider what a successful AI project might deliver, and what an AI project failure might cost.

There are other places to find clues, too. You might notice an uptick in advertising that indicates entry into a new market or category. You might read about a fall in customer service levels that could affect brand loyalty and drag down lifetime customer value. From there you might ask yourself: is this a time to buy or is this an existential threat?

Price changes, new products, partnerships, distribution deals, new know-how, are among the many lead indicators that a company is making intangible investments. When you know they’re making the investments, then you ask the big questions. Is this a real market for this company? Can they win in this area? If they win, how profitable will it be?

*Full standardized performance for BVAL can be found here