For weekend reading, Gary Alexander, senior writer at Navellier & Associates, offers the following commentary:

Raise The Debt Ceiling

While S&P 500 corporations are completing the task of submitting the unforgiving facts of their first-quarter top-line sales revenues and bottom-line earnings and profits, governments know their shareholders are helpless to sell stock in their nation, so they routinely publish scarlet red ink while living in what last week’s Economist labels “Fiscal Fantasyland.” Their forward guidance, if any, is to raise the debt ceiling.

Every day, the federal deficit hits a new all-time high, now approaching $32 trillion. Treasury Secretary Janet Yellen has set a “drop dead” date of June 1 for when the U.S. may renege on its debt payments, if we don’t raise the debt ceiling, so prepare for a month of dramatic accusations and blame-mongering.

We could service that debt with consistent GDP growth of 4% or more, but the Biden Administration and Federal Reserve have done everything in their power to slow growth to an anemic 1% pace as far as the eye can see.

In an April 24, 2023 Wall Street Journal editorial, former chairman of the Senate Banking Committee Phil Gramm and former ranking member of the Senate Banking Committee Pat Toomey, said:

“In the short term, President Biden’s regulatory tsunami will fuel inflation and make a recession more likely. In the long term, it could smother America’s productivity, wages and living standards. If the U.S. puts on a European-style rules straitjacket, American economic exceptionalism will perish.”

We’ve seen this movie before, most notably the Gingrich vs. Clinton ‘High Noon’ moments of 1995, and Obama vs. Tea Party Republicans in 2011 and 2013. We can learn lessons from these past encounters.

- 1995:

After the Republican Revolution of 1994, the new House Speaker Newt Gingrich cut funding for favorite Democratic spending programs, resulting in a government shutdown from November 14 to 19, 1995, then from December 16, 1995, to January 6, 1996.

The market took Doomsday in stride, rising 1.3% in the first 5-day span, and then +0.1% in the 21-day hiatus. In the longer run, the S&P 500 rose 34.1% for all of 1995 and another 20.3% in 1996. In the six years with President Clinton and a Republican Congress (1995-2000) the S&P 500 rose by 188%, including the dot-com bubble crash.

- August 2011 and October 2013:

Since 1996, the only government shutdown lasting over three days was October 1-17, 2013, in the Obama era. In that instance, the S&P 500 almost rejoiced – rising by 3.1% in those 17 days – so it seems that these shutdowns do not spook the stock markets.

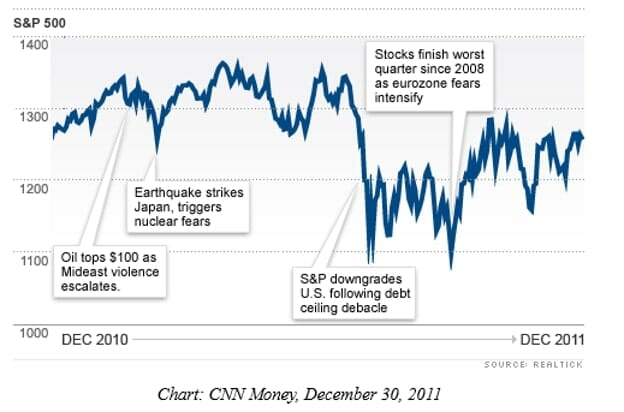

But … any prolonged debt ceiling debate, or any downgrade of the U.S. credit rating is a different story. During August 2011, S&P downgraded the Treasury’s credit rating, which sent the S&P 500 into a tailspin.

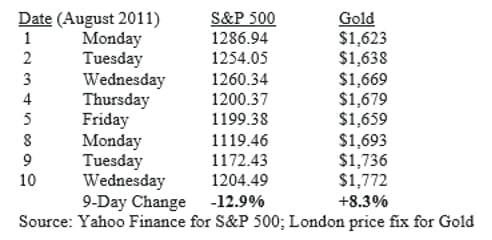

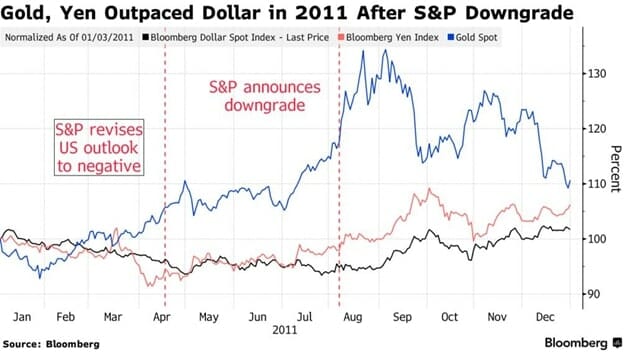

In early August 2011, gold soared after S&P downgraded the credit rating of U.S. Treasury debt – all coming during the debt ceiling debate. From $1,495 on July 4, gold rose 27% to $1,895 on Labor Day.

In the first 10 days of August 2011, gold rose 8.3%, while the S&P 500 declined by nearly 13%.

This brings us to “Gresham’s Law” – or why gold tends to rise whenever the dollar or stocks fall.

How Gresham’s Law Works Today – Examples from 1965 and 2011

Gresham’s Law says that “bad money drives out good.” Thomas Gresham didn’t invent this law, but he was the monetary advisor in the early years of Queen Elizabeth I, so the principle is at least 450 years old.

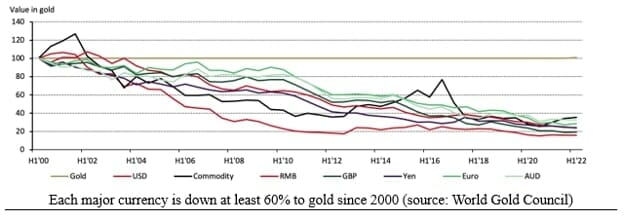

In Gresham’s day, bad money usually meant a coin debased through clipping off some of its weight, or by using base metals. Over the last 20, 50, or 100 years, most currencies have lost most of their purchasing power to gold. Here is how the dollar, yuan, pound, yen, euro, and Australian dollar have fared since Y2K:

A modern example of Gresham’s law was U.S. silver coinage in 1965 after President Johnson removed most of the silver content in favor of a copper sandwich in the 40% silver Kennedy Half-Dollar.

All of a sudden, customers would pocket the old 90% silver coin and spend the 40% silver coin, and that big old bully LBJ couldn’t stop them with his warning on the day of this Great Silver Swap, on July 23, 1965:

“If anybody has any idea of hoarding our silver coins, let me say this. Treasury has a lot of silver on hand, and it can be, and it will be, used to keep the price of silver in line with its value in our present silver coin. There will be no profit in holding them out of circulation for the value of their silver content.” – LBJ.

He was wrong. Silver gained 65% in three years, tripled in a decade, and gained 40-fold by 1980. Now, here is Gresham’s Law in action in 2011 as gold (blue line) soared when S&P downgraded dollar debt:

However, there was a sunrise in September. The U.S. economy never suffered a recession throughout all this drama. We went without a recession for a record 11 years, until COVID hit in 2020, but Europe was not so lucky.

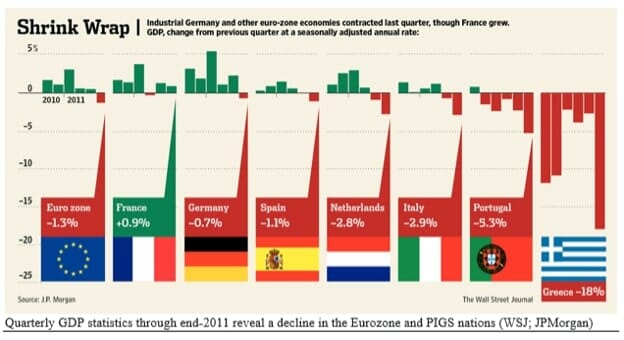

Due to their own bank problems and underperforming PIGS (Portugal, Italy, Greece, and Spain), the Euro-zone suffered negative growth in 2011, despite a weak dollar. Europe fell behind the U.S. in growth, stock market performance, employment statistics, and other metrics over the last decade.

There is a parallel today. The U.S. may seem bad off in 2023, but not compared to other continents:

The Economist’s May 4 cover article says the debt crisis is global: “Those in Europe are locked in a silly debate about how to tweak debt rules, at a time when the European Central Bank is indirectly propping up the finances of its weakest members.’

Meanwhile, economist Ed Yardeni writes, “Parisian bakers report that their electric bills have quadrupled since Russia invaded Ukraine, while the costs of flour, butter, and eggs all are up about 50%.” Barron’s adds: “The headwinds facing boulangeries in France’s capital highlight why the European Central Bank is facing a tougher struggle than the Federal Reserve.”

China’s debt figures are hidden and harder to prove, but their centralized government has buried their bad decisions in a series of doubled-down bad bets in real estate, bad banks, overseas expansion, COVID shutdown protocols, and military saber-rattling in their region.

They also are trying to rescue their weakest provinces, just like Europe did with their “PIGS” a decade ago. The Economist wrote last week (in “China’s local-debt crisis is about to get nasty”) that Beijing is pouring lots of money into Guizhou, their poorest province – a place where 32 subscribers to one of my previous global newsletter affiliations visited back in 1996, when many of us commented on the many empty buildings popping up in Guiyang.

Now, the Economist writes: “Over the past decade Guizhou, the region in which Guiyang sits, has accrued enormous debts through its building efforts—ones which it can no longer repay. Many of the region’s roads and bridges went untraveled over the past three years as covid-19 stopped people moving about.

A local bridge-builder was recently forced to extend maturities on its bonds by up to 20 years. The region is also known for its shantytowns. Guiyang is scattered with skyscrapers and green hills poking out from between them, as well as old, crumbling buildings.”

So, when you see the debt ceiling debate escalate in the next month, keep your eyes above the fray and keep asking: Which nation looks best? The U.S. will likely be #1, and gold will still trump paper.