Vilas Fund commentary for the second quarter ended June 30, 2019.

Dear Vilas Fund Partner,

The Vilas Fund, LP rose 7.8% in the second quarter of 2019, bringing the year to date return to 44.8%. The Fund has compounded at 11.5%, net of fees, since it began nearly nine years ago (August 9, 2010). This has turned a $1 investment at inception to $2.64. Relative to other actively managed value-focused hedge funds, the fund ranks as one of the best in the industry as the average fund in our category has compounded at 6% versus our 11.5% and turned $1 into $1.68. However, as you know, the fund’s results have lagged the S&P 500 by a bit over two percentage points per year since inception and by a greater amount over the last five years. Why? The persistent, and massive, lag of value stocks, now over a dozen years long, is the main reason. Some key observations and historical perspective shed more light on this and the generational opportunity before us.

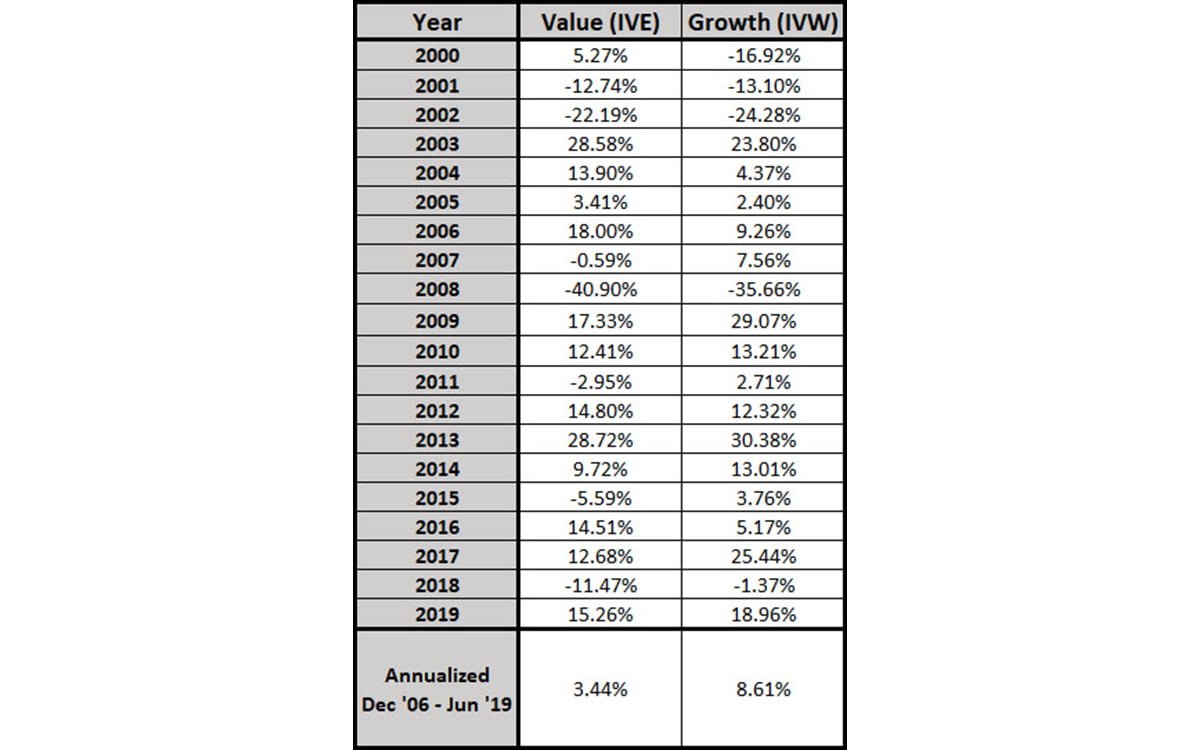

Table of Value vs Growth

The first important takeaway from this table is that Value has underperformed Growth in eleven of the thirteen years since the start of the financial crisis and, when it outperformed in 2012 and 2016, it was relatively modest. Second, Value shares, representing the cheapest half of the S&P 500 on a price-to-book basis, have only compounded at 3.44% since the end of 2006, which can basically be accounted for by their dividends. Our sense is that the return over the last dozen years is far lower, or even negative, if you use the market’s cheapest quintile or decile as the pain has been significantly worse nearer the valuation tail. Thus, there has been no real appreciation and, therefore, value cannot be overpriced. In fact, we would argue that since these businesses have grown significantly, value shares are now trading at an extremely large discount to intrinsic worth.

Historical Perspective

When looking back at my career, one of the most difficult times was during the 1998, 1999 and early 2000 period. In a variety of internal emails over that period, it was clear that my former firm was divided into the pro-growth, technology camp and those who believed that paying too much for stocks was dangerous. As I’m sure it is no surprise, I was in the latter group and was greatly outnumbered. Who can argue against future progress, solely due to price, in a convincing manner while owning hundred-year old companies like Gillette, Wrigley and a bunch of banks?

Needless to say, it was tense. We were losing clients rapidly because we didn’t keep up with Janus and the other Growth At Any Price investors. The tech stocks were going up huge percentages every day and our value names were, at best, stuck in the mud; at worst, they fell. Very similar to the environment of today.

What is the most interesting aspect of this period, at least to a finance geek like me, is that the fund I used to manage, by design, was trading at a large discount to the S&P 500: 21.7 times 2000 estimated earnings vs roughly 32 times for the S&P 500. At the exact same time, the interest rate on 10-Year US Treasuries was 6.52% and corporate bonds were yielding about 7.5-8%. I was so proud of the “cheapness” of the Fund and would, when attacked for our lagging performance, point it out internally and externally, both in conversations and emails. I knew we were exactly where we wanted to be and we were ready for whatever came next.

This former fund ended up beating the market handily between 2000 and 2002, especially once the economy started to decelerate and the Fed started cutting interest rates. In fact, at one point, this was the best performing fund in the Morningstar Large Blend space for the trailing 1, 3, 5, and 10 years, though it compounded at mid-single digit rates over the 2000-2002 period. But a gain was good in the environment when the Nasdaq fell nearly 80%.

Current Environment

Today, we have an incredibly baffling situation: the P/E of the Vilas Fund using 2020 estimates is 7.8 times earnings while the 10-Year US Treasury closed the quarter yielding exactly 2.0%. Thus, the “risk free rate” has fallen 4.5%, which would usually increase the valuation of stocks (a lot), while the P/E of a group of somewhat similar stocks to the 2000 portfolio has fallen 14 points, or nearly two thirds. In basic terms, the expected return of the former fund’s portfolio in 2000 was roughly 4% better than the 10-Year US Treasury but today, the expected return is roughly 15% higher. We believe that the differential between the earnings yield (earnings per share divided by the share price) of the cheapest quintile of the market and the 10-Year US Treasury Yield has not been this high since the aftermath of the Great Depression, if even then. This means that value stock returns will absolutely crush 10-Year Treasury returns given enough time. And most likely everything else.

Conundrum

The equity risk premium for our value stocks has risen massively, indicating either huge fundamental risks to the economy, our holdings specifically, or, for lack of a better word, hatred of publicly traded “old economy” stocks.

Since the United States is currently experiencing the healthiest consumer environment in 40-50 years and the consumer drives the economy, the first explanation of a horrendous economic outlook is implausible. Consumer wealth keeps hitting records, jobs are plentiful (unemployment is at a 50-year low), wages are rising, and debt-to-income ratios (fixed debt payments as a percentage of disposable income) are at 40-50 year lows. Since the consumer is 70% of GDP and Government, which never declines, is 20%, we find the probability of a significant economic contraction to be close to zero. Thus, the first explanation doesn’t seem to hold water.

The second possibility is that our holdings are just a few years ahead of the newspaper and buggywhip group. Their businesses, it is believed, are going to zero. Our holdings are currently concentrated in financial services, healthcare, automotive manufacturing, media, and consumer staples.

First, we see no chance of the financial sector being “disrupted” by startups or Facebook’s crypto or anything else. Why? The regulatory environment keeps the playing field even and profits must be made by all players. The key to much of the “disruption” of the last decade is simply a group of shareholders willing to forgo profits today to, hopefully, create a monopoly once they use predatory pricing to put all the competition out of business. See Amazon. This used to be illegal. With banks and insurers, it still is, or at least it is impossible to satisfy Fed and insurance regulatory requirements while losing money. Thus, the financials are in great shape and will thrive, not wilt and die like Borders Books, Sears, and others without this regulatory barrier.

With our healthcare distribution names, including CVS, Walgreens, McKesson, and Cardinal Health, we wish good luck to the newbies. Due to low profit margins and difficulty competing on price, as a co-pay is a co-pay, we find it hard to see any new entrants gaining material market share in short order. Picking up drugs locally will not go away as, quite often, you need them in a very short time frame or the flexibility to get a few pills anywhere in the US if you happen to travel and forget them. It is hard to move your prescription around from vendor to vendor. And, those 10,000 Baby Boomers who are retiring every day aren’t going to be changing their behavior much. Regardless, the noise in this case is about 99% bark and 1% bite. In other names, we still own a bit of Bausch Healthcare, purchased a bit of Allergan before the buyout by Abbvie, and then added materially to Abbvie after it fell due to the acquisition. Abbvie is roughly 7 times forward earnings with a 6.5% dividend. These names aren’t newspapers and will prosper, despite nearly all of them being priced as though they are a few steps from the grave.

And, sorry, full self-driving is not coming. Even if all technical challenges could be met, which they currently can’t, the legal system in the US and developed world will keep a human in the driver’s seat for decades. Why? If we, as humans, must participate in the driving of the car, it is our fault if the car gets in an accident and hurts someone. If the car drives without a human and harms someone, it is the manufacturers fault. The only difference between the self-driving capability of Tesla, GM and Daimler, in our opinion, is that the legal department at Tesla (which is a revolving door) is taking massive risk while GM and Daimler have 50-100 years each of watching courts “clean their clocks” if something goes wrong. Thus, the incumbents have “dialed down” their offerings significantly. This is yet another reason we are still short Tesla; let me count the ways. Our holdings – the incumbent players, including Honda, Daimler, BMW and FCA (i.e., Jeep) – will adapt and sell the cars that people want to buy at the prices they are willing and able to pay. They have the capacity, the money, the distribution, the service capability, the technological know-how, and the expertise to win.

And media content will not go away; we own a big position in Viacom. They will most certainly merge with CBS once again and create another large negotiating group. Netflix, while interesting, is slowly losing their external content as the main contenders see that they can go around them, i.e. Disney/Fox. It is only a matter of time before Netflix finds its massive internal content spending, which they capitalize, is a huge problem and that good content at a reasonable price is scarce and difficult to execute over time.

We cannot see any material possibility that our main holdings will become the next Harvard Business School case study “roadkill”. Thus, the second explanation of the high-risk premium, in our portfolio at least, is quite unlikely.

The third reason, via process of elimination, must be the explanation: people hate publicly traded value stocks. Bingo. Since the financial crisis, roughly $500 billion has been withdrawn from equity funds (per ICI), and $8.5 trillion has been invested in bank deposits, money markets, and bond funds (Fed, ICI). Thus, while $2-3 trillion should have been invested in stocks, using a 25% average of the savings, money was actually withdrawn. For the remaining money, it is clear investors are gravitating toward growth stocks at the expense of value stocks. For all the talk of exuberance and euphoria and a long-in-the-tooth bull market, the data is clear: people are scared and are acting incredibly conservatively. Thus, they are giving up large expected returns due to paranoia of the overall market and rampant fears of “disruption” of many profitable companies.

Conclusion

Investors are leaving relatively certain 15%+ returns “on the table” to pursue higher returns in “disruptive” companies that they believe will change the world for the better. It is the old “bird in the hand versus two in the bush” type of tradeoff. In essence, investors today seem to believe there are three or four birds in the bush, not just two. Therefore, let’s take the plunge and invest in unprofitable companies so we can help drive the improvement in our society or climate.

This type of thinking, unfortunately, ended very badly in the 2000-2002 period; though the names have changed this time, the results will likely be quite similar.

We believe our portfolio, at 7.8 times 2020 estimates, will crush these, to use the old term, “new economy” stocks and will become attractive precisely when these darlings are faltering, thus creating a bit of insurance and helpful diversification. We could be wrong, clearly, but when you have seen a movie before, as I did from 1998-2002, it is hard to forget the ending.

With 26 years in the business, my confidence in our fund is unwavering. Everything I have done for my education in finance, from studying rigorously for 3 years to earn a CFA Charter to commuting weekly for 3 years to the University of Chicago to get an MBA in Finance and Economics, has taught me the extraordinary power of value. Cash flow, book value, and conservative security selection matter greatly over time and though our Fund’s profits the last 3-5 years have lagged, I know finance is similar to engineering. If civil engineering concepts are not respected, a bridge or building eventually will fall. Similarly, if the financials aren’t sound, you will eventually lose a lot of money. The scientific method works in finance, too, except sometimes it just takes a little longer than we expect for it to reveal itself.

Thank you for your support; we look forward to a strong second half of the year as our eye remains on surpassing the high-water mark of last year as quickly as possible.

John C. Thompson, CFA

CEO and Chief Investment Officer

Vilas Capital Management, LLC.

This article first appeared on ValueWalk Premium