Farman Street Investments commentary for the second quarter ended June 30, 2021.

Q2 2021 hedge fund letters, conferences and more

Accidents of History

January 1951, Washington D.C. A twenty-one year old student stepped off the train into a cold morning. He didn’t look a day over thirteen, but his crackling energy and intelligence promised a bright future. In fact, he’d become one of the richest men the world had ever known.

The student found his way to a nondescript office building. The week before, he’d never heard of the entity etched on the glass. Eventually, he would own the entire enterprise which just did $35 billion in business in 2020. The student’s hero was one of his professors at Columbia University, who happened to be the chairman of the D.C.-based company in 1951. Hence the intrepid 220-mile field trip to kick the company tires.

Our student’s spirits were deflated when he found the office was locked up tight. After pounding on the door for seemingly forever, a janitor appeared and unlocked the building. Pleading his case, the student was taken to the only person working that Saturday. It happened to be the company’s president, Lorimer Davidson. For no obvious reason, Davidson spent the next four hours explaining the ins and outs of the insurance industry to his neophyte intruder. Upon returning to New York, the student put 70% of his net worth into the stock of the company.

Forty-five years later, the student would pay $2.3 billion to acquire the remaining half he didn’t own of the same auto insurer he’d visited that ancient, cold Saturday.

So it came to be, one of the greatest investors in history learned the intricacies of insurance by happenstance. That student’s name was Warren Buffett, his Columbia professor was Benjamin Graham, and the company he visited in 1951 was Government Employees Insurance Company, better known as GEICO.

The Business of Investing

"I am a better investor because I am a businessman, and a better businessman because I am an investor." - Warren Buffett

Investing is simple. Lay out money today with the expectation of receiving more tomorrow. Bonds, real estate, farmland--it’s all the same mechanics. Money now versus money later. “Investing in stocks” is nothing more than buying slivers of businesses. An intimate knowledge of what makes a business tick helps you understand what you’re buying, increasing the odds you’ll get back more than you put in. Unit economics, competitive landscape, management, culture, incentives, and dozens of other factors will determine the eventual cash flows of a business. Pile up all the cash you’re to receive as owner from now to Judgement Day, discount to the present, and you’ve forged an anchor of intrinsic value. Compare that value to the offered price. If an adequate margin of safety exists between price and the output of the business, you have a purchase candidate. Mr. Buffett’s earlier quote intimately linking business and investing carries the logic.

Easy peasy? Well, no. Simple, but not easy. That pile of future cash you’re estimating can be slippery. A lot will happen between now and Judgement Day. As Yogi Berra said, “It’s tough to make predictions, especially about the future.”

Having a business mind to count the cash is a clear advantage for investment analysis. But what if Mr. Buffett’s fluke encounter in 1951 gave him an even more decisive leg up?

Before we answer that, let’s build a basic understanding of how an insurance company operates.

How Insurance Works

A working definition of an insurance company is an entity which accepts the risks of others, for a price. Let’s make it more concrete. Say you own a house. If there were to be a natural disaster like a fire, flood, earthquake, or hurricane, your house could be ruined. Where would you live if you befell such an act of God? Could you afford the likely six-figure price tag to rebuild? Most couldn’t. The risk of such a catastrophe is unacceptable. (Especially to your banker if you have a mortgage.)

To sleep easier, you sign a contract with an insurance company. They will assess the likelihood of something bad happening, and determine how much money they would need at regular intervals to take that risk off your hands. The payments you give them are called “premiums.”

One way to look at insurance is a transfer of volatility. The alternative to buying insurance is self-insuring. We self-insurance all manner of products, services, and assets. Yet self-insurance is lumpy: you will pay nothing for long stretches and then can be hit with a big bill when something bad happens. One way to smooth out the volatility of potential loss is to make smaller regular payments to the insurance company and avoid a big one-time cash outlay. You’re typically paying a premium to achieve that smoothness in your cash flows, creating a profit for the insurance company. You’re in effect transferring volatility for a price.

“We will get hit from time to time with large losses. Charlie and I, however, are quite willing to accept relatively volatile results in exchange for better long-term earnings than we would otherwise have had. Since most managers opt for smoothness, we are left with a competitive advantage that we try to maximize. In other words, we prefer the lumpy 15% to a smooth 12%.” - Warren Buffett

The process an insurance company uses to assess the likelihood of catastrophe is called “underwriting.” Insurance companies underwrite defined risks, meaning they assume the risk and will pay the bill on your behalf if that risk materializes during the life of the contract. Insurance companies effectively accept cash upfront, in return for a promise.

It’s devilishly difficult to know the odds of any single house being ruined.1 But with enough historical data, and a big enough pool of houses, an insurance company can lean on history and the law of large numbers to underwrite risk. As the sample size grows, so does the certainty that the average is a reasonable representation of the future. The insurance company is banking that any area with higher damage than anticipated will be counterbalanced by areas with lower damage than predicted. The extremes cancel each other out and you land on your expected result. That’s how it’s supposed to work in theory at least.

“The earthquake doesn’t know the premium you got.” - Warren Buffett

In the United States, much of insurance pricing is set by state commissions. Others are set by the marginal bid in a free market. It requires precious little talent to underwrite a lot of business in an open insurance market. Simply sign a contract, sell your promise, and cash the premium check. No business selling dollar-bill-promises for 80 cents struggles to find volume. Mr. Buffett has joked that you could be alone in a rowboat in the middle of the Atlantic and just whisper a foolishly mispriced policy and brokers will come swimming from every direction. Shark fins included. The only real constraint on the volume of business you can underwrite is the amount of capital required by insurance regulators so you can (theoretically) pay up on your promises. The regulators are trying to make sure you’re good for it. Writing the business is easy--getting the right price for the risk you’re assuming is anything but.

Float Me Some Money?

Like a fingerprint, every business has a unique cash flow signature. When does money come in? When does money go out? A mismatch in flows has tripped up many a fledgling entrepreneur. Sales may be growing, while the bank account is not. You can grow yourself right out of business.

Insurance companies have special cash flow patterns. The money-in is immediate upon payment of the first premium. In some cases, the money-out can stretch for decades. It’s as if customers let the insurance company borrow the money, or float it to them. Hence the term for the funds the insurance company receives, yet knows they’re likely to eventually pay out, is called “float.” In the right hands, that float can be of tremendous value.

Is float debt? Is it equity? The answer is perhaps both. Or neither. Like debt, float is a liability that will come due eventually when a claim must be paid. But if we piled up all of the customers’ premiums, and they kept paying every year so this ball of money didn’t really change materially, our float would look more like equity.

Either way, the insurance company has use of the money from the time it comes in the door, until it departs for a claimant.

Not all float is created equal. Some contracts are short-term. You pay every month, and when nothing happens, the insurance company pockets your premium. An adverse event would cause a one-time payment from the insurance company, and a reset (upward) of your premium upon policy renewal. This generally describes automobile insurance. Crash your car this month and it won’t be long until your premiums skyrocket as you’re now considered a high-risk driver. This insurance is considered short-tail.

Other contracts are long-term in nature. Imagine a medical claim like asbestos exposure where the patient requires treatment for decades. Better hope you received enough premiums up front to cover those interminable medical bills. We can see that the duration of float varies based on the flavor of insurance and the specific contract. This duration has implications on what you can do with the float, as we’re about to see.

Two Ways to Win

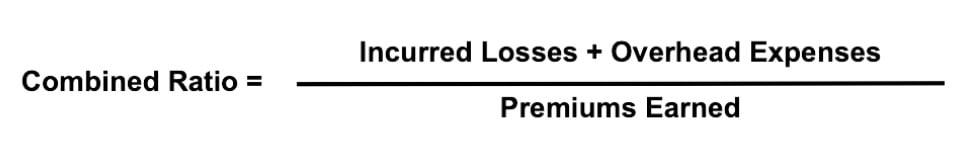

Insurance companies have their own measures for success. Like investing, it’s a matter of outlay versus eventual return. We can add up all the premiums (money in), then subtract how much they paid out in claims, plus their operating expenses like processing and corporate overhead (money out). This formula is called the “combined ratio.” A ratio below 100% implies some combination of sound underwriting and effective cost control. Over 100%, the inverse.

The combined ratio is more appropriately used to evaluate long-term results. The money-in and moneyout from contracts don’t always fall into the same year. Payments and promises don’t have to match laps around the sun. It’s not uncommon for an insurance company to look mildly profitable for several years, and then give it all back (and then some) in a single bad year. In insurance, the surprises are notoriously to the downside. One thinks of a turkey, dutifully fed by the farmer every day. Until one day in November...

In addition to the underwriting results, the company can earn income from its float. The money can be invested in nearly any asset, although state regulatory restrictions do apply. Cash flows from float have a timing element. A mismatch in the duration of the asset and the liability, can get an insurance company into trouble. Much of their planning is to match durations.

So with insurance, you have two ways to win: profitable underwriting and investment income. (You also have two ways to lose.) Now that we know some basic insurance terminology, we can marvel at the growth of Berkshire’s insurance operations.

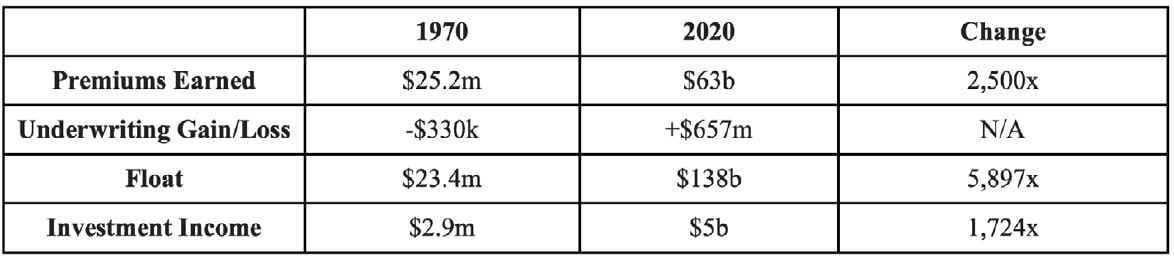

It’s remarkable to witness what fifty years of relentless progress will yield.

Portrait of a Disciplined Underwriter

“Insurance is a lot like investing If you feel like you have to invest every day, you’re going to make a lot of mistakes. You have to wait for the fat pitch.” - Warren Buffett

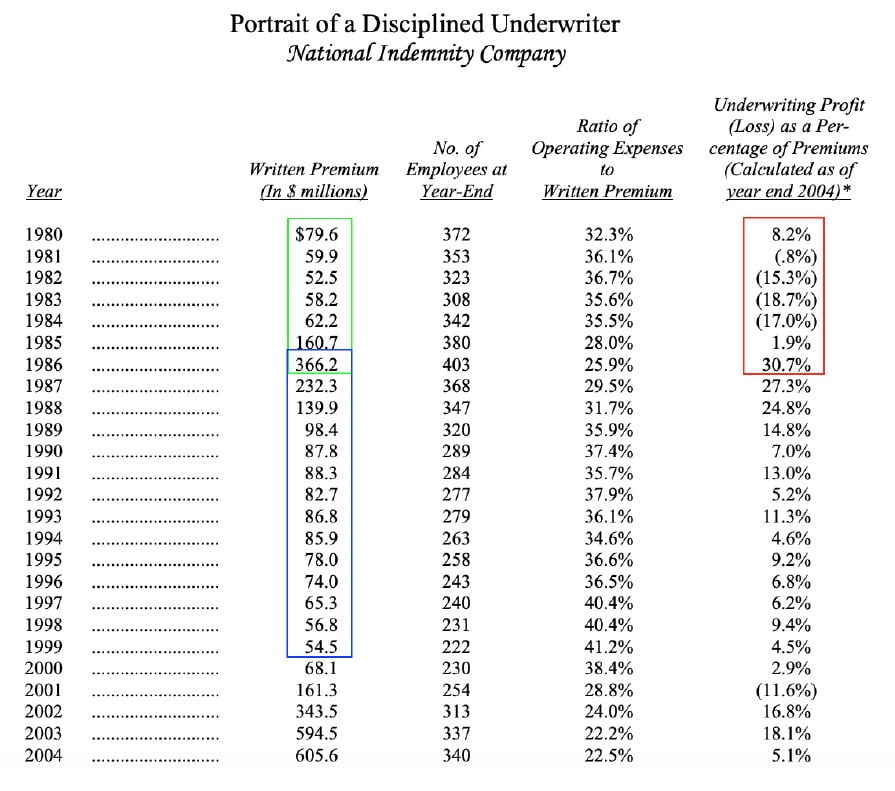

In Berkshire Hathaway’s 2004 Letter to Shareholders, Warren Buffett provided the following table showing the results of National Indemnity, a subsidiary insurance company inside of Berkshire.

It’s instructive to compare two time periods.

From 1980 to 1986, National Indemnity grew premiums written from $79.6m to $366.2m, a 29% compound annual growth rate. The company was sprouting like a weed and firing on all cylinders, right? Well, not quite. The far right column shows the company had underwriting losses in four of those seven years. Yet we need more context. At risk of oversimplification, let’s look at 1982 specifically. We can say that National Indemnity paid 15.3% interest to put $52.5m into Warren Buffett’s hands. That sounds like expensive money to borrow, but remember the 10-year US Treasury paid you a fat 13% back then. So for two percent over the risk-free rate, NICO got money into the hands of a genius, when stocks were at generationally low valuations. Not so appalling when framed in that light.2 From 1980 to 1986, Berkshire’s insurance groups earned more than $575m in cumulative net investment income and realized gains, overcoming their underwriting losses from the right hand column. (Remember our two ways to win?)

Next look at 1986 to 1999. Premiums actually shrunk at a -13.4% compounding rate.3 National Indemnity was damn near wound down. Yet every year showed consistent underwriting profits, meaning Mr. Buffett was getting paid to borrow and invest the money through one of the biggest bull markets in history.

Well-executed insurance contracts are the original negative interest rates. But it requires near-psychopathic underwriting discipline.4

“It takes real fortitude – embedded deep within a company’s culture – to operate as National Indemnity does. Anyone examining the table can scan the years from 1986 to 1999 quickly. But living day after day with dwindling volume – while competitors are boasting of growth and reaping Wall Street’s applause – is an experience few managers can tolerate.” - Warren Buffett

Insurance + Investing

Our original thesis was that Warren Buffett’s exposure to insurance was just as important to shaping his investment success as his love affair with business. We’ll close by examining the key principles of successful insurance and what they tell us about becoming better investors.

“[We] price our super cat exposure so that about 90% of total premiums end up being eventually paid out in losses and expenses.” - Warren Buffett

It’s perhaps no accident that Mr. Buffett attempts to price Berkshire’s expected insurance results to match the hurdle he’s looking for in an investment, roughly 10%. A return on capital is a return, regardless if it’s from insurance operations, a Berkshire Hathaway Energy wind or solar facility, or replacing rail at Burlington Northern. It’s all investing.

“The most important thing in investments is not having a high IQ, thank god. The important thing is realism and discipline. The same thing applies in insurance underwriting. You can do it without calculus. You can really do it with a good understanding of arithmetic and an inherent sense of probabilities. From the investment standpoint, if we’ve had any distinguishing characteristics, it would be in terms of realism and discipline. Generally that means defining what you don’t know. In insurance underwriting it’s the same thing. You have to be realistic about what you understand and can’t understand. You have to be disciplined about turning down all kinds of offerings where you aren’t being paid appropriately.” - Warren Buffett

Key Principles of Insurance

- Maintain an attitudinal advantage of underwriting discipline.

- Know the risks you’re underwriting.

- Beware the aggregation of risk.

- Get paid an appropriate premium.

- Be patient and willing to lose business.

1. Maintain an attitudinal advantage of underwriting discipline.

As we saw with National Indemnity, it can be painfully difficult to maintain underwriting discipline. The fear of missing out on easy premiums can lead to underpricing risk and courting future losses. “Everyone else is doing it” isn’t much of an analysis. Those who can delay gratification have a major advantage.

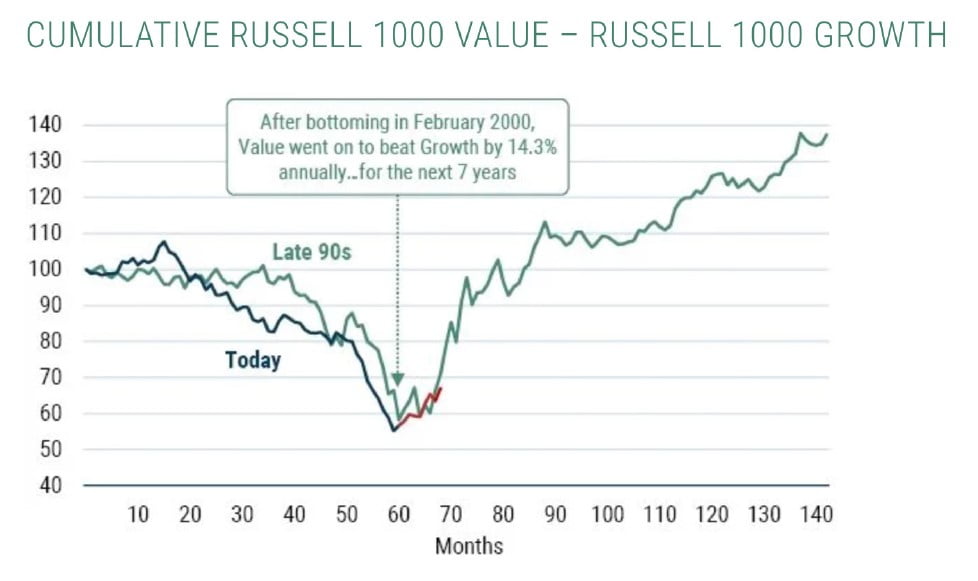

The same is true for investing. When people get excited about an asset, price action can create its own upward momentum. A rising price is all some need to justify participation (and validation of their acumen). Discipline goes by the wayside and tethers to reality are severed. Fundamentals are either tortured or abandoned as a quaint, limiting belief. Fantasy worlds can persist in markets for surprisingly long periods. But eventually, economic gravity reasserts, cash flows matter, and bubbles burst. Stay disciplined; don’t chase the crowd.

2. Know the risks you’re underwriting.

A well-structured insurance contract is explicit about what is covered and what is not. Risks and potential triggers are well-defined.

A good investment thesis is also an exercise in knowing the risks you’re underwriting. What if competition heats up, crushing industry returns on capital? What if growth is less than expected? Inflation, deflation? Rising or falling interest rates? Technological disruption? Wars or pandemics? You get the idea.

Essentially, we’re assessing the odds of something bad happening that will shrink our portion of the pile of future cash. How can we lose? Premortems are an invaluable tool in analyzing what might wrong. Postmortems are also a must to help avoid making the same mistakes twice. We all have blindspots and it’s easy to miss a risk you failed to underwrite. The key is to close the feedback loop of learning to avoid repeat.

3. Beware the aggregation of risk.

Insurance companies must mind the aggregation of risk. Meaning any one contract can be fine, but when many contracts are summed together, the risk exposure becomes more than intended. A single event can wipe out decades of progress if you aren’t paying attention.

An investment portfolio can also suffer from the aggregation of risk. A single position can be fine, but the holistic risk surface may spell disaster. What if your portfolio is very tech-oriented and the world subsequently changes less than investors expect? (It happened in 2002-’03.) What if your portfolio is basically a one-way bet on interest rates moving in a certain direction? (See: bonds.) We can unwittingly make bold market calls without even realizing it.

Mea culpa: value portfolios carry their own biases. One is an assumption that less disruption will occur than anticipated. “This time is different” is considered value sacrilege, even though occasionally it really is different. The other is a bias for reversion toward a generally improving mean. Value investing is all about not getting too excited or despondent about the world. It can be boiled down to “this too shall pass.”

A solid, long-term combined ratio signals an insurance company is being paid a satisfactory premium for the risks they’re assuming. (Recall: money in vs. money out.)

In a way, the price we pay to acquire ownership of a business is the premium for the risks we’re underwriting. Paying a high price for an entity full of business risk is not a recipe for success. Yet it can certainly work over shorter periods of time with Mr. Market’s mood swings. In the short term, it’s decidedly better to be lucky than good.

Inversely, the lower the price we pay for a given unit of risk, the better we can expect our outcomes over many transactions. Paying a low price is like receiving a high premium. Little wonder Mr. Buffett has quipped, “Price is my due diligence.”

Know your risks, and don’t overpay for what you’re underwriting. A high price for any asset implies an expectation of a smooth upward future. Ferraris driven at 100 mph should beware even mild speed bumps.

5. Be patient and willing to lose business.

As National Indemnity so dramatically illustrated, it’s better to lose business (reduced premiums) than to lose money (underwriting losses). Sometimes you have to shrink to survive.

Being a professional investor can be the same. One is reminded of Jean Marie Eveillard’s quote at the height of the dot-com craze: “I would rather lose half my shareholders than lose half my shareholders' money.” He got what he wished for.

At Farnam Street, we can sympathize. We’ve lost clients due to a lack of “action.” Our patient, businessfocused style isn’t for everyone. Who wants to watch paint dry? You have to be a little nutty to enjoy cataloging the gradual, dogged, incremental progress as a business fights for inches over long holding periods. Las Vegas wasn’t built on delayed gratification.

And boy can stock prices languish, sometimes for years. Why aren’t we doing something?! Actually, we are. We’re letting the intrinsic value inside the company accumulate from serving customers, making payroll, reinvesting into the business, and building the brand. If we have the good sense to be patient, we can maintain faith that Mr. Market will eventually appreciate cash.

In 2017, we made the decision to not charge management fees on excess cash in portfolios we manage.5 This led to a dramatic drop in revenue (like -50%) for our small firm. All our bills, vendors, and employees still needed paid; owner take-home pay took the blow like a vintage uppercut from Mike Tyson.

Operational leverage cuts both ways. But we couldn’t find enough attractive risk-reward scenarios in businesses we could understand, at prices which made sense. So we waited. And waited...

A global pandemic in March 2020 eventually brought prices back to Earth (for a spell). We knew we were underwriting plenty of risk (especially short-term), but the prices we were paying to back the businesses and management teams we chose carried favorable odds. Like good insurance, the premiums made sense for our underwriting risks.

In hindsight, we could have made even more if we’d chosen more speculative enterprises. We can debate the addressable market of those willing to pay millions of dollars to ride a rocket into lower orbit while people are hiding in their homes from a global pandemic and around 10m in the U.S. weren’t even paying their rent. There were plenty of other ways the last year could have unfolded where our conservatism would have allowed us to survive when others may not.

Today, most market prices have relaunched into the stratosphere, but there are pockets of interesting businesses and valuations that keep us searching. Return expectations from today’s high perch should be muted,6 but the longer-term future remains incredibly bright.

The cycles continue.

An Encouraging Chart

As always, we’re thankful to have such great partners in this wealth creation journey.

Jake

Farman Street Investments