Askeladden Capital letter for the first quarter ended March 2019, discussing positive carry investments and free cash flow.

Dear Clients,

From 1/1/2019 through 4/5/2019, Askeladden Capital Partners LP returned in excess of ~ +28% gross, representing a positive spread of over 11 percentage points compared to the +16.8% return of our benchmark, the S&P 1000 Total Return, over the same timeframe. Net of all fees, Askeladden Capital Partners LP returned in excess of ~ +24% YTD, a positive spread of over 7 percentage points.

Q4 hedge fund letters, conference, scoops etc

Additionally, as will be discussed in more detail later, Askeladden Capital Management has more than doubled FPAUM since year–end. Beyond portfolio gains, roughly three million dollars of capital were added by both new and existing clients, including two new seven–figure accounts. New clients added since last summer – all of whom initially found and reached out to us, not the other way around – include:

- individual investors who are early to mid–career professionals (a category of client we particularly love, as we discuss later),

- current or former fund managers,

- (U)HNWs and a family office who are current or former LPs of funds like David Einhorn’s Greenlight Capital, Zeke Ashton’s Centaur Value Fund, and Allan Mecham’s Arlington Value.

Cumulatively, since inception on 2016–01–08 through the market close on 2019–04–05, we have returned over ~ +159% prior to the assessment of any fees, compared to a little over +59% gains for our benchmark. Given our modest management fees, our approach of paying the vast majority of business expenses ourselves rather than charging them to LPs, and the fact that our performance allocations are assessed only on outperformance vs. the benchmark rather than on absolute performance, our returns net of all fees still substantially exceed benchmark performance.

By our (rough and unaudited) calculations, multiplying our estimated YTD results by audited results as of 12/31/2018 (and normalizing audited results for the full fee structure, which some investors, such as myself, do not pay), a hypothetical investor who joined at inception and paid full fees all the way would now have in excess of a ~ +118% net return, again compared to about +59% for the benchmark.

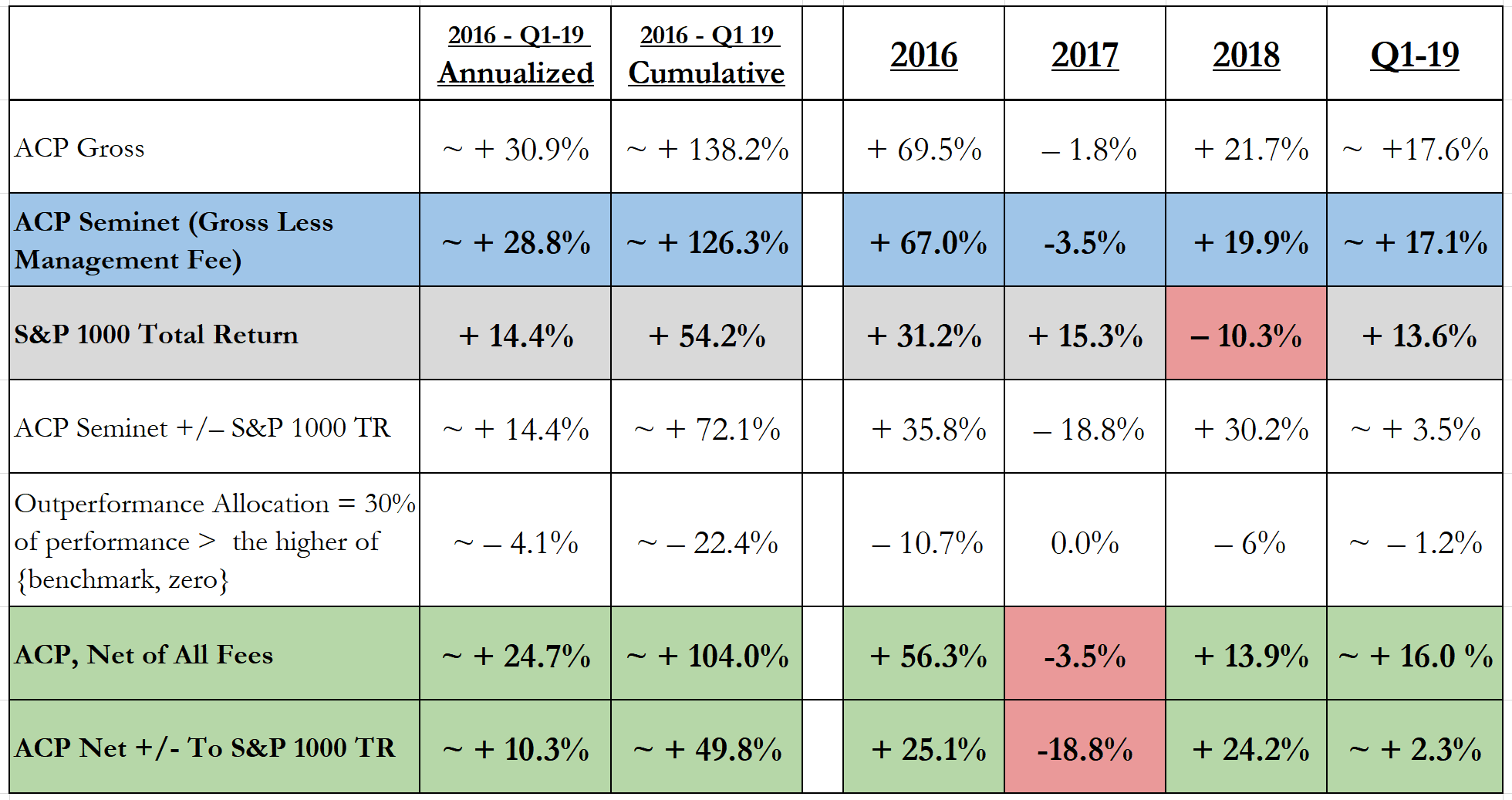

The table on the next page displays the more modest, but still very respectable, performance results as of the end of Q1 2019 (3/29/2019), prior to the release of earnings reports at several portfolio companies that spurred further gains over the ensuing first week of April. Please see important disclaimers in the appendix.

When assessing our results, please remember that we do not utilize leverage in the form of either margin or options, and in fact have at times had significant cash balances. We run a long-only, unlevered portfolio. We also tend to avoid investment in heavily cyclical or levered companies.

Finally, we do not own any high–flying, popular growth stories (such as the “FAANG” stocks, Tesla, or SaaS companies.) As such, we believe that over time, most of our outperformance can be attributed to our process of bottom–up identification and selection of undervalued securities, which we can consistently and repeatably over time, rather than any exogenous tailwinds in market sentiment.

That is not to say that we haven’t benefited from a favorable market environment – of course we have – but rather to say that we haven’t, typically, been exposed to the portions of the market that have performed the best over recent years (i.e., growth / technology.)

The purpose of this letter is to discuss three separate, important topics. In order:

- Our recent performance.

- The continued refinement of our investment strategy.

- Recent business developments.

Let’s start with the first.

(1) Performance Review: Please Don’t Get Too Excited

As I usually do during periods of good performance, and for the benefit of clients who have joined in the recent past, I would like to stress that our investment strategy is categorically NOT designed to outperform every year, let alone every quarter. Our approach is not designed to sidestep market downturns. Our approach is not designed to sidestep bad quarters at our portfolio companies. Our investment strategy is designed to deliver superior performance over multi–year horizons, albeit with a lot of interim volatility.

As such, and especially considering the concentrated nature of our strategy, it is difficult to assign much meaning to performance over short timeframes. Our results in any given month or quarter cannot reasonably be extrapolated to any other time period. The last three and six months (plus a week) have been very kind to us, continuing the broader trend of our performance since inception.

However, even if we manage to outperform our benchmark over the long term, there can and will be extended periods of underperformance as well. As some of our longer–term clients are undoubtedly aware, 2017 was one of those years, where we were down ~4% net vs. the index being up slightly over 15%. Even with the underperformance that year, our 3.25–year performance has been very strong, but nothing about performance in the other years could have suggested 2017 was likely (or vice versa).

In short, the nature of long–term value investing means that gains can often be very lumpy; for example, substantially all of our 2018 gains can be attributed to the months of January and February, with our performance throughout the rest of 2018 roughly flat (with volatility along the way). Similarly, our strong gains to start 2019 do not necessarily presage further gains the rest of the year.

In fact, conversely, if the valuations of our stocks rise faster than their intrinsic values (as has happened in Q1 and through the first week of April), then that necessarily diminishes our future return expectations. So while it is always gratifying to be rewarded for our decision–making, portfolio gains often necessitate harvesting and eventual redeployment; if we want to continue to earn superior returns, we need to continue to identify superior opportunities for capital deployment.

To this point, due to the combination of higher valuations and a higher cash balance, while our expected forward three–year portfolio CAGR at our underwritten valuations was in the high 20s as of merely weeks ago, it is today between 23 and 24%. While our forward outlook is still very robust and we are extremely happy with the portfolio as–is, we are mindful that just as today’s returns are the result of research conducted quarters or years ago, so too will future returns be the product of research conducted today and tomorrow, and decisions made thereupon. Investment success is neither guaranteed nor automatic.

Thus, as always, we are focused on making additions to our watchlist, which is the lead measure of future investment opportunities. It now stands at 140 companies, nearly halfway to our eventual target of 300, despite several notable losses to M&A. On the portfolio front, we track our progress by the actual business performance of our portfolio companies. Fundamentals are a more accurate barometer of our decisions. Business performance of our portfolio companies is the lead measure of investment returns: if we correctly underwrite business performance, which in turn drives our valuation estimates, then investment performance will naturally follow.

With the one exception of unexpectedly stellar results at GlobalSCAPE (GSB) released at the end of February – results so strong, in fact, that we were buying a substantial number of shares the next day, when the stock closed up 30% above its prior close (yes, you read that right – see the portfolio update for a discussion of how understanding transactional utility is helping us make better decisions) – we by and large did not have any material fundamental surprises during the balance of Q1 (since our last letter in late January).

In aggregate, the rest of our holdings reported results that were more or less in line with our expectations – some modest shortfalls, some unexpected positives, but on the whole nothing major. Given that we believe our portfolio will achieve a 23%+ CAGR over three years if our expectations are met, this is good news.

Even if results materially underperform what we underwrite, we believe we will do just fine. That is the point of margin of safety. Of course, we are always looking to “highgrade” the portfolio in terms of both business quality and valuation; if we have the opportunity to sell something we like a lot to buy something we love even more, we will usually take that opportunity.

As usual, please see the attached, 21-page clients–only portfolio commentary for more detailed discussion of fundamental results and valuation at each of our portfolio positions.

(2) Cash and Carry: Refining our Focus (or, why we no longer own LQDT)

The purpose of this section is to discuss how we are refining our investment strategy going forward, through the lens of why we no longer own Liquidity Services (LQDT), which was once our largest position. Thus, we believe its elimination from our portfolio is worthy of some discussion.

Long–term clients are likely aware that I try to be actively countercyclical with my focus and emotion: when everything is going well from a market standpoint, I like to focus on mistakes, or things we could have done better, to temper ego and ensure we’re not getting complacent. When everything is not going well from a market standpoint, I like to focus on successes, on non-investing things, to remind ourselves that we are more than our current mark–to–market and allow us to make objective decisions away from the pain of loss.

Much of the analysis here may ring a familiar note from previous individual conversations or previous letters, but since I have come to some formal conclusions, it makes sense to thoroughly codify them so everyone’s on the same page. We’re going to start with the underlying theory, then progress to the specific takeaways.

--

Transforming Mental Models into Money

It kills me not to know this,

but I’ve all but just forgotten:

What the color of her eyes were,

and her scars, or how she got them?

- “Savior” by Rise Against (my favorite song when I was 16)

I’m often asked how mental models help me as an investor. The answer, as I’ve discussed in previous letters, is that mental models just generally help people make appropriate decisions: they help doctors make better diagnoses, they help engineers build more user–friendly products, and so too they help investors achieve superior returns.

One mental model that I often return to is memory – few domains of our lives better highlight our tendency for overconfidence. We can’t remember where we put our keys down five minutes ago, yet we insist that our version of what started our feud with our bitter archrival thirty years ago is the correct and only version of the story. (Never mind that the other fellow is equally convinced of his side of the story.)

This is an especially pernicious and overlooked cognitive bias when it comes to business and finance; as I’ve cited previously and repeatedly, there is some great discussion about hindsight bias in Richard Thaler’s “Misbehaving” (M review + notes) where he explains why many corporate managers are afraid of taking risks. Imagine taking a smart risk: for example, betting on a coin flip where you lose $1 if it comes up heads and win $10 if it comes up tails.

That is a bet you should always take (assuming you are not $1 away from starvation.) Yet if the coin comes up heads, bosses often forget that it was a great risk to take in the first place, misremembering that it was always a huge risk and this coin was always destined to come up heads. And so the manager will be punished for the bad results, even though the decision process was great: a clear failure of process vs. outcome thinking.

Attempting to improve memory, whether via mnemonics or other techniques, is essentially a complete waste of time – very little marginal utility, and a huge opportunity cost. As Don Norman says in “The Design of Everyday Things” (DOET review + notes), writing is a great technology – we should use it more.

I follow this guideline for my own investment research; we extensively – often exhaustively – document what we know and why. This allows us to assess our past decisions, based on information available at the time, without the interference of hindsight bias (either positive or negative). Of course, this approach only works if we actually go back and assess those decisions.

A major challenge, of course, is sample size. Just because a stock goes up does not mean our thesis was correct; just because a stock goes down does not mean our thesis was incorrect. Moreover, any individual situation may have so much luck or randomness that it may be difficult to draw conclusions from what are, essentially, isolated anecdotes.

That said, however, now that I am able to look back on the many investments made over Askeladden’s three years of existence – in addition to my experiences as an analyst for two years prior to Askeladden’s launch, and my experiences as an individual investor before that – there are some clear trends that emerge, which we are using, going forward, to refine our strategy: both in terms of what we invest in, and in terms of what sorts of companies we spend our time working on in the first place.

Where'd We Come From… And Where Are We Going?

To start with, I have been forthright in many conversations about the fact that my investment strategy when I launched Askeladden was heavily influenced by heavy losses I had suffered in the prior year in my PA (personal account), when I was working as an analyst at a fund (and, not coincidentally, being massively deprived of sleep to the point where there were severe physical health impacts – and undoubtedly, similarly brutal impacts to my decision–making quality.)

In some ways – certainly not near-term financially! – that experience was very beneficial. It taught me to avoid (or at least be extremely cautious around) low quality businesses run by low quality people, highly leveraged companies, companies with extreme customer concentration, companies with tremendous leverage to commodity prices or other cyclical, uncontrollable macro factors, etc. My PA read like a laundry list of everything that could and should go horribly wrong, and I deserved the pain that I received.

Askeladden’s portfolio performance since inception has, thankfully, not seen me repeat these sorts of mistakes. But that’s not to say that I haven’t made mistakes. I’ve previously discussed, for example, how we made money off Windstream (WIN) by virtue of luck when we probably deserved to lose it all (it seems we needed one more lesson on the perils of a bad business mixed with leverage). Again, process vs. outcome.

There are other companies we had modestly sized positions in – such as Aspen Aerogels (ASPN), NCS Multistage (NCSM), and Fiesta Restaurant Group (FRGI) – that show up as either neutral or even positive to our P&L in total, but that would have resulted in meaningful losses if we had continued to hold them until the current time. ASPN is a story that in some senses is somewhat similar to LQDT, except without the fundamental downside protection of the balance sheet.

My sense, without the benefit of any specific data to prove it, is that we have probably on net benefited from luck since inception; i.e. our returns are modestly higher than what we probably deserve. It is reasonable to expect that there will be periods where the opposite occurs. It is also reasonable to try to prevent ourselves from being exposed to such bad luck, by not making decisions that could potentially land us in trouble.

More prevalently, however, the mistakes that come to mind are those of omission or opportunity cost rather than per–se actual losses (or actual losses that could have been). Trying to avoid losing money is obviously an important part of trying to make money, but it is not a goal that should perversely prevent the achievement of the first goal. If Rule Number One is “don’t lose money,” then the term “lose money” should be properly defined in all of its various forms – which I think many people fail to do.

The Fallacy of WYSIATI (What You See Is All There Is)

I am going to make a heretical statement, which is: I believe many value investors are irrationally afraid of losing a little bit of money in the absolute, salient, visible sense, and irrationally complacent about losing a lot of money via the hidden but still very real avenue of opportunity cost.

Let me elucidate. From a simple mathematical perspective, say you have $100 today. Here are two options; you are free to choose between them. You can:

A. Have $110 in a year’s time, or,

B. Have $105 in a year’s time.

Option A is obviously preferable by any rational individual, right? Yet I’d argue that many value investors repeatedly – and stubbornly – choose Option B, and pat themselves on the back for doing so.

Why? Well, I only gave you the endpoint. Let’s add the interim data:

A. You have $110 in a year’s time, but only after having seen your money rise to $150 and then fall back to $110 in the interim, or,

B. You have $105 in a year’s time, but get there in a very steady stream, as if you own a CD or savings account that pays a 5% APR – each month you just get closer to your $105.

Even though it is obviously economically preferable to choose option A, the reality is that from an emotional standpoint, most people will vastly prefer the lived experience of Option B.

On their recent earnings call, Franklin Covey (FC) CEO Bob Whitman shared this wonderful quote from Richard Feynman that I hadn’t heard before:

Imagine how hard physics would be if electrons had feelings!

And so it is with finance. Whether or not Feynman ever actually said that, Richard Thaler has something to say about that too. Behavioral biases at play here include:

- The endowment effect and hedonic adaptation– in our hypothetical example, once our account reaches $150, we feel entitled to have our $150 – it has become part of our property – and it no longer makes us happy. However,

- Loss aversion / deprival superreaction syndrome – losses cause twice as much pain as gains cause pleasure. And of course, finally,

- Recency bias / hyperbolic discounting – we place far more weight on recent experiences.

So, in Option A, we were briefly a little happy to make $50, and then we adapted to it because it became part of our endowment. Then it was taken away from us: we were really angry/sad about losing $40, and so even though we’re up $10 to end the year, we’re left with a bitter taste in our mouth. Because we “lost money.”

Conversely, in Option B, we never had to go through the pain of loss – we only enjoyed the pleasure of gain. There were only good, happy feelings; no bad, sad ones. We never “lost money.”

And yet it is, again, obviously infinitely economically preferable to choose option A. You are $5 worse off in Option B than you would have been in Option A. (That is, unless you count the cost of the stress–management class your doctor ordered you to take on the day you lost $40).

Therefore, if you volitionally choose Option B over Option A in the real world, your future self is losing $5 that it could’ve had. And yet because this loss is not salient – i.e. the $40 of losses in option A is very visible and heartbreaking, whereas the loss in Option B is somewhat ephemeral and nebulous, and you never see it directly – it does not affect us emotionally.

And this is why many value investors seem to consistently prefer Option B to Option A in real life – they would rather “lose” money invisibly through opportunity cost (such as by holding too much cash, or not investing in perfectly reasonable investment opportunities with attractive teens–plus forward returns potential) because it is less painful to not make money you never see than it is to have to suffer losses that you are forced to see.

That is to say, at least based on many letters I’ve read (admittedly mostly from managers I don’t know personally), many value investors are happy to have earned middling returns for long periods of time, because they were never exposed to the risk of a downturn. Well, if that downturn ever comes, the people who earned better returns the whole way will still be ahead of those who turtled. (See, for example, my analysis this past fall about Howard Marks’ new book, in which John Hussman is a cautionary tale.)

Many readers will likely point to FOMO and other similar phenomena to suggest that the average investor probably behaves inversely to this hypothetical. I would not argue with that contention; it is probably an accurate one. I am not suggesting that in market environments like the late 1990s, value investors should attempt to keep up with their benchmark by taking more risk. That’s not the appropriate approach.

But it is important to use the right base rate. The average height of the general population in the U.S. in 2019 is likely not particularly helpful to determining the likely height of a given female in Asia in the 1800s.

I am starting with the premise (base rate) of value investors who, like myself, tend to avoid commodity exposure, tend to avoid heavily cyclical companies, tend to avoid heavily leveraged companies, tend to avoid hot growth stories trading for extremely rich multiples that imply vast gains far out in the future, tend to be fearful when others are greedy, and so on.

With that starting point, among that demographic, I think it is very clear that there is profoundly irrational loss aversion with regards to actual mark to market losses, and profoundly irrational complacency with regards to opportunity costs.

Without the benefit of empirical data, but with the benefit of having read writings by many, many value investors, I would posit that more money has been lost by value investors since 2008 – in terms of subsequent foregone gains and refusal to invest at reasonable forward CAGRs – than was actually lost peak to trough during the financial crisis. And this money was lost because it is more painful to go through a large 50% correction all at once than it is to give up 10% of foregone gains per annum over many years.

And what is risk anyway? Risk, in my view, is anything that gets between you and the achievement of your goals. If your goal is to have a lot more money down the line than you do today, then you may not be taking any “risk” in the conventional sense owning a U.S. treasury bond.

But I’d argue it’s pretty risky to try to achieve your 30–year retirement strategy with a portfolio of U.S. ten years. There is some merit to the idea of trying to achieve “hybrid” sub–equity–like returns with modestly super–bond–like risk, but for portion of the average investor’s portfolio dedicated to long–term growth rather than funding short–term needs, it is probably not the most adaptive approach.

It is interesting to note that when asked about his biggest mistakes, Charlie Munger – who, counter to our own newfound philosophy at Askeladden, strongly believes in holding lots of cash all the time – names not an absolute loss, but an opportunity cost, as his biggest mistake (Belridge Oil).

In sum, you can lose more money trying not to lose money than you’d ever think you could. While I haven’t done the math, I’ve probably “lost” as much or more money owning Liquidity Services for years than I did with some of the ill–advised investments I made that actually turned into bigger capital losses on my tax forms. There is more than one way to invest badly, and I’ve had experience with at least two of them! It is likely that I will find more such bad investing approaches over time. I’ll let you know when I do.

The Little E-Commerce Platform That... Couldn’t. It Just Couldn’t, OK?

Enough theory; let’s get to specifics: why Askeladden no longer owns Liquidity Services (LQDT), which was, at inception, our largest position, and was, while not our largest position for quite a long time now, still a material position until late 2018. This is not so much about LQDT specifically as it is about our process more generally. I will work in other examples.

Liquidity Services operates several online platforms for the disposition of surplus assets, ranging from returned retail inventory like jeans and laptops to used “yellow iron” heavy equipment. One of their businesses, GovDeals, is particularly attractive. It is asset–light, has 90% gross margins, and has a near–monopoly on the municipal government market, with a long track record of double–digit revenue growth and a long runway for continued double–digit revenue growth. Its other lines of business vary in their attractiveness; long story short, however, my general thesis on their business was – and is – that e–commerce is beneficial for both buyers and sellers for many types of surplus assets, and as with many other forms of commerce, the transaction of surplus assets is likely to continue to move online over time.

Nothing has occurred in the past three years to cause me to doubt this thesis; volume growth in their core business has actually been better than what I expected, for the most part. However, on the flip side, the company is currently not consistently producing any material amount of free cash flow (excluding irrelevant swings in working capital that are not true, sustainable free cash flow) – while, at the same time, it has (and continues to) massively dilute shareholders by issuing a lot of stock–based compensation that is treated, in earnings reports, as a fictitious expense that is not part of “Adjusted EBITDA.”

Nonetheless, there is reasonable support for the idea that some day in the medium term (say, the next 3–5 years), they will be earning reasonable margins on their volume, and the combination of these margins, along with continued revenue growth driven by the secular trend toward e–commerce, would support an enterprise value substantially higher than that which the company trades at.

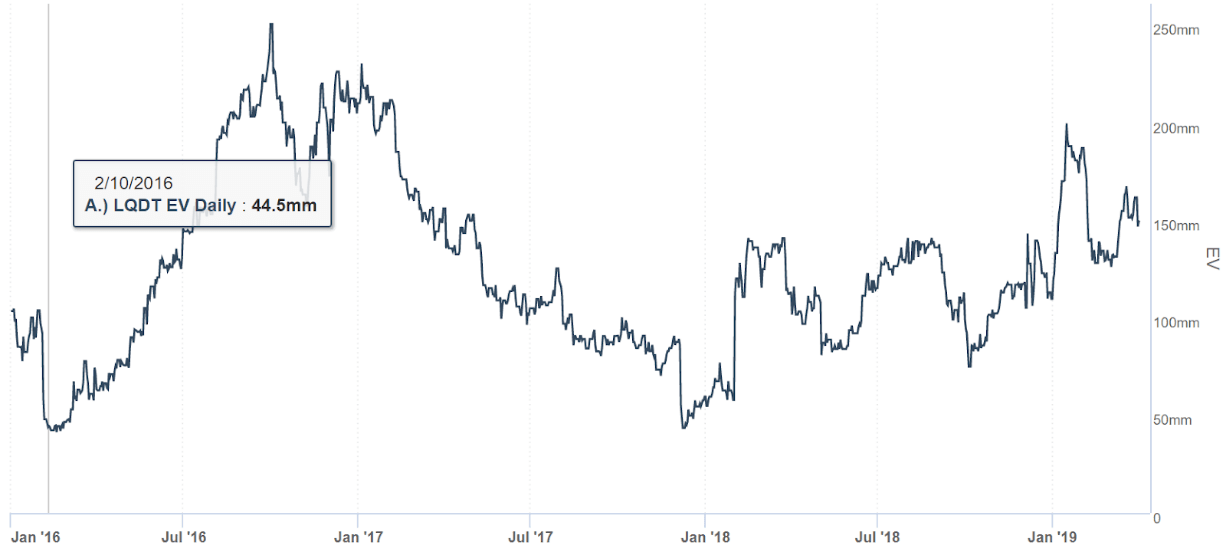

Focus, here, on my use of “enterprise value” rather than “market cap.” LQDT has spent two decades building its business, and the value of merely its Google SEO position (let alone the technology backing its platforms) has often exceeded the near–zero enterprise value it has traded for at times. Here is a chart from my research tool, Sentieo, demonstrating how LQDT has traded for an enterprise value below $50 million at several points, vastly below replacement value of the business (consider that they have been spending millions of dollars annually just to upgrade their platform, and tens of millions just to run and maintain it):

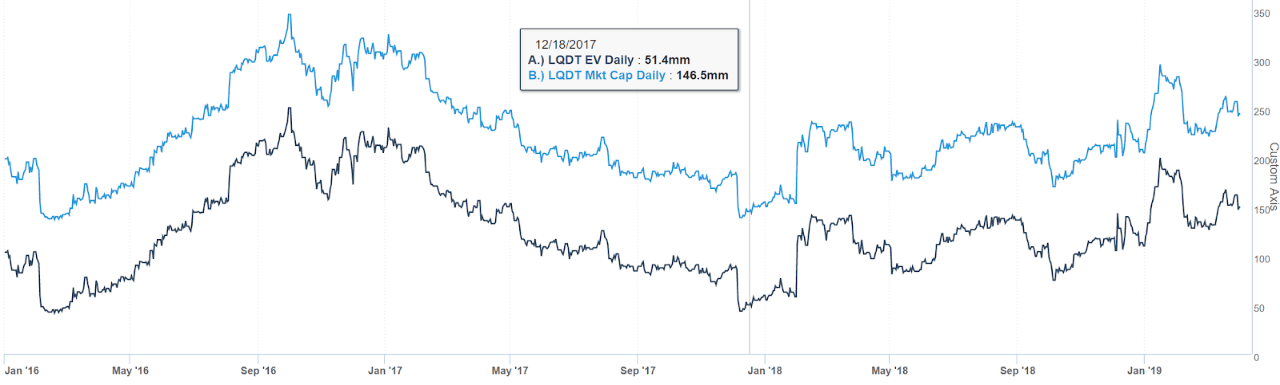

In reviewing my history with the stock, it is extremely clear to me that the company’s cash balance was a large part of our investment thesis, in terms of downside protection. The above chart grows somewhat more illustrative if we superimpose market cap data on it as well: at many points during our ownership of LQDT, the value of the company’s cash actually exceeded the market’s valuation of its operating business:

Even today, LQDT’s cash represents more than 30% of its market valuation.

There are nuances here, such as the amount of cash that should be treated as “float” from customers rather than free and clear cash, and so on. These are not really relevant in the grand scheme of things. The point is that my investment thesis, reductionistically, was as follows:

A. There was extremely low fundamental risk of losing money due to the combination of the low valuation on the operating business, and the massive pile of cash.|

B. Although the exact timing and magnitude of future cash flows was difficult to estimate, it is clear that any rational valuation of the business would result in a price meaningfully higher than what it traded for during most of our ownership.

Nothing that has happened has altered my view on either of these two pillars of the thesis. I still believe that LQDT is worth more than it trades for today; in fact, I believe it’s worth materially more than any of the prices I’ve sold it for over the past half a year. I think $8 – $12 is a reasonable range of value depending on what the future holds, with a higher valuation certainly possible.

So why doesn’t Askeladden own it anymore? And why were we selling it at less than the low end of what we thought it was worth? Because there are better opportunities available to us, that are more aligned with the base rate of types of investments with which we have been successful.

What The Dividend Growth Investors *Should* Have Been Doing

For the purposes of our discussion, let’s bucket the world into two types of investments.

- “Positive carry” investments, and,

- “Future monetization” investments.

What is the difference? For the first category, we are talking about companies that provide a consistent source of annual returns, in some combination of cash flow and growth.

For example, imagine a company which owns a website that sells e–widgets. Demand for these e–widgets is extremely consistent (they are the e–equivalent of toothpaste), and demand grows at an above–GDP rate. As a result of the company's business model, it has no material growth capex requirements, and free cash flow scales linearly with revenue. The e-widget company has neither net cash nor net debt on its balance sheet.

An investor purchases shares at an 8% free cash flow yield, with an expectation that free cash flow will grow 4% per annum for the next decade. That 8 + 4 = 12 is our “positive carry” – maybe some years it will be a little more, and some years it will be a little less – but on average, we can expect that intrinsic value will steadily accrue to us over time if the investment is purchased at that valuation.

There are nuances regarding reinvestment of interim cash flows, etc – for the purpose of this analysis, please ignore them, as they are not the point; just assume that the cash flows are reinvested (i.e. via buybacks at a constant multiple to original purchase price) such that the compounded annual rate of return is 12%. (This is similar to, but different from, the idea of ‘compounders’ in that I am not so focused on the company having a very high earnings growth rate, but am still focused on consistent and predictable value creation over time.)

For the second category, “future monetization,” imagine a company which owns a large amount of land near an expanding metropolitan area. The company has de minimis ongoing operating profits that offset de minimis ongoing costs, such that the company has no positive carry, but also does not have a “negative carry” (i.e. the inverse of a positive carry). An investor purchases shares in the company, with the expectation that the land will be fully monetized in one go – a bullet maturity, so to speak – ten years from today, at a value 3.1 times what the stock trades for today. Further assume that all wells drilled in the area have been bone–dry and there will be no miraculous mineral–resources discoveries (i.e. this is not the Barnett Shale circa 1996.)

If you do the simple math of taking 3.1 and raising it to 1/10, you arrive at the conclusion that over a ten year horizon, both companies should offer identical 12% annualized compounded returns (again, assuming reinvestment at the same rate of return at the e–widgets company.)

So, should we be agnostic as to buying the e–widget company versus the land–bank company?

Absolutely not. Even at the same prospective return profile, the e-widget company is a massively superior investment opportunity to the land company.

There are a number of reasons for this. The first is simply that, all things being equal, money now is better than money later. The e–widget company will generate cash flow that it can reinvest accretively if it sees an opportunity – maybe it has an investment opportunity with a better–than–12% IRR – or it can find a way to return that cash flow to us owners, in which case maybe we can reinvest it accretively at a higher rate of return.

Conversely, the land–bank has no options between today and ten years from today. If land nearby is available for a steal, it might not be able to buy it unless it had debt financing (which is far harder to get when you’re not making any money.) If the stock market collapses and fantastic opportunities are available right and left, the land–bank cannot repurchase its own shares at a dramatic discount, nor can it pay out a dividend so that shareholders can purchase shares of other companies.

The second reason has to do with the investor’s ability to assess progress. One of the reasons that, generally speaking, I tend to prefer company with somewhat predictable year–to–year results, that are not overly influenced by macroeconomic factors or industry–specific idiosyncrasies, is that the more “noise” there is in the results, the harder it is to find the “signal.”

With our hypothetical e–widgets company, it is very easy to tell if they are on track or not. If we were expecting them to grow 4% and their revenue instead shrinks by 10%, then that’s a pretty big indicator that something strange is happening. We probably need to investigate, and revise our thesis.

Conversely, with the land bank company, there’s very limited incremental insight as time goes by. The thesis is that this land will be valuable in 10 years because someone will want to build a suburb on it. But other than the occasional anecdotal asset sale, and/or vague directional understandings of which way the population is expanding, there remains tremendous uncertainty, from the analyst’s standpoint, over the eventual outcome. It could be really good… or we could’ve entirely wasted our time for ten years.

The final reason has to do with the fact that, contrary to what many value investors like to espouse, the public market is not a private market. It is patently absurd to approach minority public–market equity investments with the mindset that you’re evaluating a private business with a permanent time horizon. We are not Warren Buffett; we are not actually buying that company in whole. Minority public shareholders very rarely have the level of influence over the company’s direction that their economic stake would suggest.

Moreover, for anyone who is not a buy–and–hold investor with an infinite horizon, multiple rerating makes up a significant component of returns – for a strategy like ours with a typical time horizon of about three years from an underwriting perspective, it is probably in the neighborhood of half, though it might vary from 30 to 70% depending on the situation.

As such, consistently and repeatably identifying not only companies whose businesses will do well going forward – but also companies whose stocks trade for too low a price relative to those future results, whose stocks will therefore appreciate even faster than the compounding of intrinsic value via business performance – needs to be a core competency for any public–markets value investor with a non–infinite timeframe.

The long and short of it (pun not intended) is that for our purposes, it is really not helpful if value is being accrued, but is not recognized in the public markets until some indefinite point in the future. Unless management is taking action to remedy that gap and boost future value – for example, by repurchasing shares – then we should want the price to rise as high as possible, as quickly as possible.

As one of our clients – a professional investor who is one of the smartest people I know – pointed out to me once, low turnover is overrated. If you are capable of finding some stock that will go up a lot, really fast, then selling it to buy some other stock that will go up a lot, really fast, why would you ever not want to do that? (Tax considerations can be factored into the equation and don’t change the takeaway.)

Of course, unfortunately, our belief is that it is difficult to have any expectation of multiple rerating over a very short time–frame – i.e., several quarters, or perhaps even a year or two. We do not believe that we are capable of consistently identifying near–term “catalysts” that will cause a stock to rerate, and as such we do not attempt to do so as part of our process. However, in our experience, businesses with a positive carry tend to relatively consistently and reliably rerate to an appropriate value if given enough time.

This is due to a phenomenon that was once elegantly described in metaphor by investor Donald Yacktman: imagine a beach ball held underwater. The deeper you push the ball, the higher it must eventually spring.

Cash flow and/or earnings growth is the buoyancy, the force that propels that beach ball; it is reasonably irrelevant what specific form those arrive in (dividends, buybacks, organic investments for growth, accretive M&A, etc). If a company generates a ton of cash that it deploys accretively – or, if a company delivers strong growth – then at some point, it becomes difficult for the market not to recognize that value. There are clearly positive recent trends in the business (the cash flow and growth), and if the stock has not risen – let alone if it has fallen – then the multiple will have compressed to a level that is quite absurd. Like a spring uncoiling, this sort of setup presages strong future returns. And, again, if that value is not realized, any positive–carry company can do something about it if they want to.

Returning to the example of the land bank company, however, there is no similar force that drives rerating, that drives market reflection of the value that is being created. The land just sits there, being land–y, until one day we are able to sell it. Maybe. Hopefully. In the real world, there is probably actually a negative carry: property tax, SG&A, someone to maintain the property so that it doesn’t turn into a jungle, etc.

Each year, the potential payoff may have grown closer, but its magnitude and timing is still very uncertain. So such assets, like Liquidity Services, can often languish in the market until or unless they are either bought by an acquirer. Earnings are far superior and more reliable downside protection than assets, for most circumstances that matter to public–markets investors.

The Counterfacual, and Schrodinger's Stock

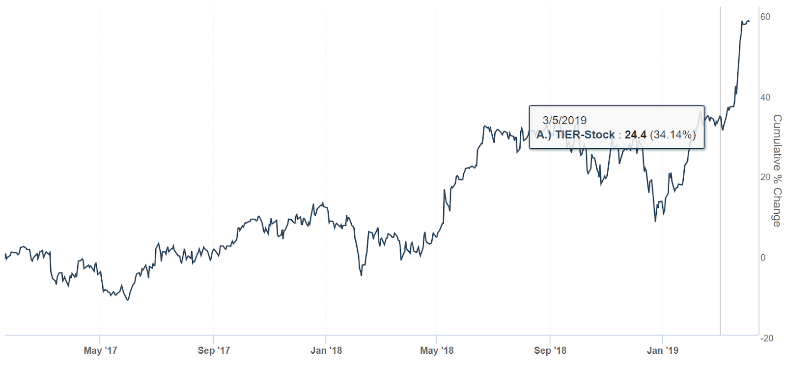

This is not to say that such situations can’t work out well. Many of our friends and fellow investors work on these sorts of situations, and have done well with them. We have even owned some investments in this category that have done well (not per–se from the standpoint of our portfolio, but from the standpoint of a retrospective on the multi–year journey of the stock, with enough time that luck plays less of a role). Take TIER REIT, a Texas–focused office lessor that we had a small position in several years ago, when non–Texas investors incorrectly assumed that my native state’s economy was far more tied to oil than it really is.

TIER was attractive because its market valuation represented a substantial discount to the appraised net asset value of its office properties, which were for the most part relatively liquid and salable assets. We took the unusual step of conducting primary research – we do not usually do this, but since we are located in Texas, it seemed like the appropriate call. We spoke to a number of real estate brokers to better understand the company’s properties and the appropriate cap rates for valuing them, and came to the conclusion that even if we used extremely conservative, macro–shock type assumptions, the company still traded for a meaningful discount to its intrinsic value.

What was the problem, and why did we sell it reasonably soon thereafter for a modest gain? The positive carry problem. While there was real estate value to be unlocked, TIER was subscale and had too high an SG&A load for its size. Thus, while the portfolio was very attractive at the property level, once burdened by public–company costs, shareholders were not looking at a huge ongoing value creation opportunity (unless rents increased meaningfully and/or they were successful in their efforts to develop several new properties at attractive ROIs, neither of which we were willing to model aggressively.)

As such, TIER fell into a category of company that we like to term a Schrodinger’s Stock: like the proverbial cat in Schrodinger’s thought experiment, there are two possible states: dead or alive. But you can’t tell until you open the box, and until then the cat exists, like the Wasp’s mother in Ant–Man, in some sort of Quantum Realm where she is neither actually dead nor alive.

It was clear to us that TIER was worth more dead than alive, but in the public market, it was, like the cat, in a quasi in–between state – it was not at all clear whether it would “live” as a public company (in which case shareholders would probably not see great annualized returns) or whether it would “die” by M&A or liquidation (in which shareholders would see greater annualized returns).

Of course, many companies fit in this paradigm to some degree. There is always a “spread” of potential futures that is not known or knowable until the actual future materializes one day, and that is not a problem.

It is, however, a problem if in one quantum state, you don’t make any money at all, which is often the case for asset plays and other non–carry–based investments in completely different areas (such as early–stage venture investments, where the strategy is essentially “consistently lose money for a really long time in hopes that one day you luck upon something valuable.”) I’m generalizing the analysis to situations where you either make a lot of money one day or you don’t, but you don’t make much in between and may not have a chance to get out once you get in.

It turns out that when the box was opened, the cat was dead; TIER would’ve delivered perfectly respectable returns. We made our last sales in January 2017 at $17.48 and then a little above $18. It was recently acquired by / merged with another REIT for consideration that the market is currently valuing at $28.75, which appears to be at or above TIER’s NAV (which has compounded faster than we would have expected, probably because we ended up with the “good” and not “bad” macro situation from the perspective of rents, cap rates, interest rates, etc – an outcome which was not guaranteed.)

We are happy to see TIER achieve a reasonable value for their shareholders, but that doesn’t change the fact that we don’t regret for one minute not continuing to own it. If not for the recent buyout/merger, it is not obvious to us that TIER would have consistently provided the sort of returns we target. The company might eventually have been bought out at a similar valuation anyway… but had it happened another two or three years down the line, returns would have been nothing to celebrate.

Contrast that with Pointer Telocation (PNTR), a telematics company we took a tiny (we’re talking like less than 20 bps in core accounts) starter position in during December 2018. That company, too, was recently acquired/merged for a substantial premium. A key difference, however, is that even had this not happened, we are confident we would have continued to earn solid returns. The company was trading at an attractive free cash flow yield, with no debt, and was continuing to grow its subscriber base at a rate well in excess of the growth rate implied by the free cash flow yield (assuming a standard 10% cost of equity capital.)

As such, had PNTR still been available today for a reasonable valuation that met our return hurdle, chances are we would be making it into a decent–sized position. (As it stands, we don’t think much of its acquirer, ID Systems (IDSY), don’t think much of the combined company’s leverage ratios, don’t think much of the current valuation, and as such have no interest in owning the combined entity.)

And this brings us back to Liquidity Services (LQDT). As we noted, the company continued to grow its core revenue organically – at attractive double digits / teens rates in some of its business lines, in fact. This is clear value creation. We also thought that the company’s investments in its platforms would deliver clear payoffs, ranging from operating efficiencies to increased recovery on assets as they were exposed to more buyers. While more difficult to quantify, we viewed this as value creation as well.

On the flip side, however, the company did not generate meaningful free cash flow, and it issued absurd amounts of stock–based compensation. Unlike some investors, we treat SBC as a real cost – for good reason that is explained by this real–life example of LQDT. The combination of some cash burn and the stock based comp continued to erode any positive value creation that was occurring elsewhere. Had the stock–based compensation truly not existed, then we might be singing a different tune here.

We have mostly had something roughly around $10 as the midpoint of our fair value range for LQDT, and for the most part, it has traded below that range, with one exception: in late 2016 /early 2017, when the business traded for around this price, I was mistaken in overestimating the operating momentum of the business and the length of time their transformation would take. I take full responsibility for that analytical error; in retrospect, I should have been more aggressive in reducing the position size then.

However, the bigger error was the category error. We were lulled into a false sense of security by the balance sheet (assuming that the market would recognize its value and thus not allow it to trade at such a low valuation again.) We were wrong. We also failed to place enough emphasis on the fact that while we were waiting for the transformation and eventual payoff to occur, we weren’t getting paid.

And so as the transformation took longer and cost more than we expected (even with underwriting we thought, at the time, to be conservative), the problem was that we were not getting paid at all. Not only were we not getting paid, but there was no future value accruing like the buoyancy of the beach ball. Quarter after quarter, year after year, we weren’t forced to reduce our valuation estimates… but we weren’t able to increase them, either.

And this is a problem. If you are underwriting with a 10% equity cost of capital, if your underwriting is accurate or a shade conservative, then you would hope that – over time – your valuation of companies should rise by 10% or more per year (netting out any cash paid out as dividends, buybacks, etc.) Obviously, not every company will follow a perfectly linear trajectory; some will do better than you ever expected, and some will do worse. But on the whole, most of our investments have, over time, become more valuable, thanks to the force of positive carry.

LQDT… not so much. Our valuation remained stuck in the mud at $10, and the stock remained stuck in the mud at $7 – $8 (if you were lucky.) And so what we eventually realized is that: a) either we are incapable of underwriting this one correctly, or, b) even if we are underwriting it correctly, it is impossible to assess the probability that the market will agree with us within any span of time that would deliver the 20% or greater CAGR we target. Since there is no positive carry with LQDT, if our timeline or magnitude of future payoff expectations prove wrong, there is no consolation prize in the meanwhile.

And as our watchlist continued to expand, we realized that we had many companies available to us that – unlike LQDT – did offer strong positive carries. The example I discussed above (PNTR) is somewhat representative; while that is not one of the companies we ended up purchasing more of, it does cleanly demonstrate the counterfactual: even if PNTR never rerated (whether in the public markets or via acquisition), we likely would have earned a high single digit to perhaps low teens annualized return over any long enough time horizon, simply via the accretion of cash flow and growth.

Thus, we return to the e–widget vs. land–bank hypothetical: while no two companies are purely on one side or the other, and there is a lot of simplification in the hypothetical (namely, the elimination of all business uncertainty and volatility), the point remains that PNTR was more like the e–widget company: it is much more in our sweet spot, and it will relatively consistently and predictably accrue value over time.

LQDT is more of a gamble on a future payoff: it may be a good bet to make at a certain price (such as when it traded for an enterprise value that literally assigned almost no meaningful value to the operating business), but it is not a bet to make in a large size, especially with better opportunities available.

Net-Net, Net-Schmet

But what about all the cash that was supposedly protecting our downside? Never mind the cash. We placed inappropriate emphasis on the value of the cash. Some cash on a company’s balance sheet is good; it reduces risk. Infinitely more is not infinitely better. It is not our job to own cash with a call option on returns. It is our job to deliver superior investment performance over time, with some degree of consistency and repeatability (i.e., delivering outperformance over most, though not all, three year horizons).

That obviously necessitates investing in companies with balance sheets that can survive the risk of path–dependency; any geometric series that includes a zero multiplies to zero. We still focus on companies with net cash or modest leverage; most of what we own tends not to have more than ~2x net debt to EBITDA, and the stuff we own with more leverage than that tends to be limited from a top down basis, and in very few cases do we own anything with anything close to an LBO–like balance sheet.

I should also note that I don’t want people to get the impression that our strategy is as simple as running a screener for “FCF yield + growth = 12.” That’s not it. Sometimes we find such easy opportunities, but oftentimes they are hidden. A core premise of our strategy is that we shouldn’t try to compete with computers; if our “edge” can be easily reduced to a quantitative screener that a computer could apply, then it is likely our edge would vanish over time – hence the heavily qualitative aspect of our research, as computers tend to be much better than the human brain at quantitative tasks, and much worse at qualitative ones.

Positive carry can take many forms, and could be hidden or lumpy. For example, Franklin Covey (FC), as well as former portfolio holding MiX Telematics (MIXT) – the latter a peer to PNTR – went through transitions where their financials looked terrible: free cash flow was down, as was revenue and margins and everything else. But they were still accruing value in a clear and consistent manner; that value has been subsequently recognized by the market: they were investing in building a subscriber base with a tremendous long–term payoff of stable, high–margin recurring revenue.

Not all value has to be obvious on the P&L; I think it has now become clear to many value iinvestors that “money–losing” companies such as Salesforce (CRM) have in fact been accruing tremendous value over time. That’s not to say that we have any opinion on Salesforce’s valuation, or more than a cursory understanding of its business. But a company doesn’t have to have current earnings or cash flow to be obviously creating value.

Other sources of positive carry could be more lumpy and less predictable: accretive M&A, margin improvement opportunities, etc. But that’s where judgment and expertise comes in; we feel like we’ve built a pretty good database of case studies, and have the ability to analyze some of these situations.

As has been discussed in previous letters, we were champions of Franklin Covey long before the story was obvious to the vast majority of market participants; the same could be said for something like an AstroNova (ALOT) or a DMC Global (BOOM). Although, as has been discussed previously, much to my chagrin, we more or less completely whiffed on BOOM (we made some money on it over time, but not nearly as much as we should have.)

So, to sum up: while some value investors try to put a comforting, tangible number on downside to value (often using assets as a floor), we’ve been humbled enough to realize that irrational market pricing can just keep getting more irrational, and there is really no floor to what something can trade for on any given day.

Carry Saves The Day

However, if we instead focus on downside to carry – meaning, in a reasonably bad scenario, will this business still be throwing off enough cash flow and growth to earn us a reasonable return over a long enough time period? – we end up with a much more helpful analysis that we believe is much more consistently predictive of future returns.

This is not to say that we are always going to get these analyses right, of course; there are sometimes surprises to the downside on revenue growth and margin profile – we recently went through one with Emerald Expositions (EEX), which we no longer own, though it was a small position to begin with anyway. And we have gone through the same issue with something like a Lydall (LDL) over the past year, as we have discussed (and continue to discuss) in the attached 21-page portfolio commentary. There are many other examples, most of which we have thankfully not owned, but merely observed.

But the difference between LDL and LQDT is: while we may suffer mark to market periods of a languishing price in both instances, one of the two has the capacity to do something about it. Lydall has decided, for various reasons, to invest its capital in organic growth and acquisitions rather than share buybacks, but either way, the company will deliver strong free cash flow and reasonable growth in earnings that we believe will lead to a future price meaningfully above the current price in the mid–$20s.

And if it doesn’t, Lydall will always have the opportunity, in the future, to buy back its own shares to correct the gap – which LQDT could have, with its cash, but didn’t. From a psychological perspective, it’s often easy to “turtle” and not invest in positive–ROI opportunities when you have lots of assets, but aren’t making any money (or are even losing some.) I should have known this – it was the exact position I was in when I launched Askeladden (I had plenty of savings, but no cash flow.)

Finally, to return to the issue of opportunity cost, it is worth noting that far greater than our actual mark–to–market losses on LQDT (if you measure our “high water mark” with the position and our subsequent sales of it) is the fact that we could have invested in other opportunities that, cumulatively, have performed extraordinarily well over the same time period.

Via inversion, in fact, our performance with LQDT (and LQDT–like investments) has been so bad in aggregate that even if all of our other positions were to correct downwards by 30 – 50% (which would be a Very Bad Day), then performance would normalize between the two.

Or, in other words: even if our strategy blew up tomorrow, we still would have been far better off focusing on companies with strong ongoing value creation than on companies with less value creation, but more asset protection. (Note that the two are correlated because you usually don’t value a company on the basis of its assets unless it isn’t currently earning a lot of money using those assets.)

Thus my mindset has shifted over time, both with regards to the kind of companies we own, and the amount of cash we want to have in our own portfolio in any environment where there are plentiful opportunities.

Caveats, There Are Many

This is not to say that we’re not focused on downside protection – don’t get the wrong impression. Again, not losing money is obviously an extremely critical element of being able to make money, and our feelings about leverage / cyclicality / customer concentration / etc remain as they always have been.

Nor is this to say that we feel like we have a mandate to be fully invested and will buy anything and everything at Nifty Fifty or 1999 valuations. That is absolutely, categorically, definitively not the case. We are extremely valuation-sensitive, perhaps too valuation-sensitive, if anything.

Similarly, none of this is to say that you can’t have bad experiences with businesses with a positive carry. We bought Windstream at nearly a 20% free cash flow yield, if memory serves; the company is now bankrupt. But there were many other factors at play: an astronomical debt load, extremely high capex requirements, a business model I didn’t fully understand etc. These are factors that should have kept us away; they didn’t.

These are factors that should have caused us to lose money; luckily, they did not. But they did reinforce lessons that I apply today, such as avoidance of leverage and capital intensity, avoidance of industries in secular decline, taking it slow with positions in new areas (“familiarity risk,”) and so on.

All in all, we just believe, based on our own experience, that once you eliminate the things that can kill you – leverage, commodity exposure, customer concentration, etc – then the thing most likely to damage value investors’ performance is not making too many bad investments, but rather making too few good ones.

As long as we are operating within our circle of competence, without overly exposing ourselves to risk factors that can really take us down, our focus will be more on maximizing the reasonably achievable rate of return (by focusing on positive carry) than by trying to minimize capital exposed (by focusing on asset downside protection), and thereby losing more money than would have been likely in the first place.

Scars, and How We Got Them

The scars of losing money in 2015 have left their mark on my investment strategy. Some of those marks were, and are, good: if you burn yourself on a hot stove, you shouldn’t touch a hot stove again. That’s natural. That’s called learning. It is an important cognitive lesson to learn, as Laurence Gonzales discusses in “Deep Survival” (DpSv review + notes).

But some of those marks were bad, and I’ve needed to retrain myself: as Laurence Gonzales discusses in “Surviving Survival” (SvSv review + notes), resilience is important. You can’t allow yourself to hide in your house for the rest of your life because you once left your house and something terrible happened to you. If you allow yourself to do that, then the bigger damage is done not by the trauma, but by your response to it.

Our job is not to avoid risk entirely; think of us like an insurance company – if we never write any policies (i.e. never make any investments), we will never make any money. Our job is to avoid risks that we cannot price appropriately, and to smartly bear the ones where we think we are getting paid far more than adequately for the risk we are bearing – like all of the various insurance companies under Berkshire Hathaway.

Of course, there is a “never say never” component here – there may still be situations I encounter where it is worth taking a modest position in something that doesn’t have a positive carry, but has tremendous future monetization potential. There are perhaps a few positions around the edges in our portfolio that have those characteristics to one degree or another.

Again, this is also not perhaps an indictment of the category of businesses so much as our ability to assess them; there are numerous friends of mine who invest with different principles than those I’ve laid out above, and some of them have longer–term track records I can only hope to have one day. However, I tend to view these individuals as exceptions to the rule.

By and large, everything we own today can either be valued on current cash flow, current earnings, or a look–through to earnings before readily identifiable discrete investments that are voluntary rather than necessary to the business remaining competitive. We believe this is a much better position to be in, and hope that our results, over the long term, will reflect this.

(3) Business Update: Scaling

As the myth goes, the three–year mark is when a fund manager looks up and sees money falling out of the sky. I used to joke about this, but didn’t think it would literally turn out to be true.

Well, at least in Askeladden’s case, it’s been true so far. Money has fallen out of the sky, and lots of it. As of last September, we had less than $3 million in fee–paying AUM. As of the last letter (late January), we noted that we expected to have in excess of $5 million in fee–paying AUM pro forma for capital commitments that we expected to be funded in the near future.

All of those commitments arrived, and then we received some more: as of the date of this writing, Askeladden Capital has in excess of $7 million of actual (not pro forma) fee paying capital. Some of this, of course, is due to our YTD performance. The majority of the increase in capital since late last year, however, is due to capital additions from both existing and new clients, including two 7–figure accounts from new clients, and six–figure additions from three existing clients. Excluding a blood relative, new clients added since Q3 2018 include:

- Two retired U.S.–based fund managers and one active internationally–based fund manager,

- A single–family office, and,

- Seven individual investors.

Among these new investors are current or former clients of funds like David Einhorn’s Greenlight Capital, Zeke Ashton’s Centaur Capital, and Allan Mecham’s Arlington Value.

Not counting “prospective” clients whose eventual investment is still uncertain, we also expect a high six to low seven figure amount of capital, in the aggregate, to be contributed in the near term (i.e. the next several months) by another three fully arms–length new clients (two individual investors and an international family office), as well as some family and friends clients. Therefore, using the same metric we did last time, pro forma for capital contributions that we believe we will receive in the next few months, we should exceed $8 million in fee–paying AUM sometime this summer (assuming flat portfolio performance.)

Moreover, as is to be expected, many of our new clients start with a smaller amount of capital, and ramp up over time as they grow more comfortable with our process, or their liquidity frees up from other investments they currently hold and are not yet ready to monetize (a common problem).

For example, based solely on our existing client base and the clients I believe are extremely likely to join in the near future, without the benefit of any other new clients, I believe it’s reasonable to expect breaking the $10MM AUM mark sometime later this year or at the very least in 2020, as we expect several of our larger clients to add substantial additional capital, and several of our smaller clients to make additional contributions that – while smaller individually – are still very meaningful relative to their current account size.

Commencing Active Marketing

It is worth noting that all of the above is capital that found me rather than vice versa; most clients are familiar with the fact that since inception, I have not actively pitched Askeladden to anyone other than family and friends – I have simply made my letters and other materials available via my website and distribution channels like Seeking Alpha and ValueWalk, and like–minded investors could contact me if they liked what they read.

That approach has been more successful than I had any right to expect, and by all means, it seems like it will continue to be successful. However, at the same time, I’ve come to have a more mature and respectful appreciation for the value of marketing. It may not be my cup of tea personally, but it is a valuable business discipline – this was the conclusion I reached after thinking through the takeaways from books like Peter Thiel’s “Zero to One” (Z21 review + notes), and David Ogilvy’s “Ogilvy on Advertising” (OnA review + notes). While product is undoubtedly critically important, my judgment as an investment manager is that for many of our portfolio companies – Franklin Covey (FC) and GlobalSCAPE (GSB), for example – the organization’s financial results are heavily influenced by the performance of the sales team.

That said, marketing is valuable for a business’s owners, but often not so valuable for a business’s customers, at least to the extent that resources are diverted away from servicing existing customers towards acquiring new ones. I have always found it strange that many “emerging” fund managers spend a substantial portion, and sometimes the majority, of their time trying to “pitch” prospective clients.

While this likely works out well for the manager (who raises capital), what happens to the clients (whose existing capital is not the primary focus of the manager?) This is not merely a hypothetical concern; two of the nicest and highest–integrity fund managers I know both told me about their own challenges balancing research with conventional “roadshow” active marketing, even though they absolutely wanted and tried to focus on research. There is literature out there, I believe, on newer and smaller managers outperforming; the process of scaling adds operational time commitments at the same time as requiring many marketing hours.

Of course, this sort of concern tends to conflate with another issue: the biblical truism about pride coming before a fall. Marketing usually tends to occur when things are going well. Because, let’s face it, few investors want to invest in a fund that hasn’t been doing well! But when things are going well are also when it’s easiest to get complacent, and thus when the manager should be spending the most time making sure they are conducting thorough research and making appropriate decisions thereupon.

Last fall, before the influx of new investors, it became clear to me that if I wanted to reach a reasonable amount of critical mass in a reasonable time, I needed some outside help and should not continue to rely solely on people finding me without me doing any active outreach. I have been running an extraordinarily lean personal cost structure since Askeladden’s launch; I live in my childhood bedroom in my parents’ suburban house and my personal expenditures are largely limited to groceries, my gym membership, my phone plan, and anything discretionary I want. I am single. I do not go out and do many things, or travel very often. I mostly just read books, cook, and occasionally go backpacking through the wilderness.

This is of course a sensible arrangement for now, but not one that is sustainable indefinitely: someday I will not be 25 and single and living at home with no material recurring bills. Someday I will have a family of my own, and the accompanying higher cost structure. If there is ever a time to establish your business, it is before you throw that additional commitment of emotion and time into the mix.

So it became clear to me that, A, it would be optimal to scale now rather than later, and B, trying to do so myself would likely not be effective (it’s not my area of expertise), and would also consume so much time that it would risk damaging portfolio results. The ultimate conclusion was, obviously, that I needed to retain outside help, just as I do for accounting, compliance, tax preparation, and other business functions which are necessary and important but not my core expertise or a good use of my time to handle myself.

But who? My conversations with other fund managers made third–party marketing sound like a bit of a nightmare: it usually didn’t work, it usually involved lots of time and expense, it usually involved lots of poorly–vetted meetings with “prospects” who really had no intention of ever investing – summarily, consuming time and resources without yielding a payoff. So I knew that if I wanted to go down that route, I needed to be very selective and partner with the perfect person.

Enter Maury McCoy, a fellow Texan (though he’s originally from Omaha). Maury, the principal and sole employee of his own third–party marketing firm, McCoy Associates, first connected with me via Seeking Alpha several years ago. He’s a micro–cap enthusiast and continued to follow my work even after I told him in no uncertain terms that I’d never hire a third–party marketer. (As the kids say, “that didn’t age well.”)

I selected Maury primarily for three reasons. First, Maury has a long and successful history of raising capital for concentrated small / micro–cap long–only funds, highlighted by his work with well–regarded investment manager Brian Bares (Bares Capital Management) of Austin, TX. Maury started working with Bares Capital when it was of directionally similar size to Askeladden (single–digit millions in AUM).

Many years later, today, Bares’ latest Form ADV suggests the firm currently has several billion under management. Of course, unlike Bares, we are looking to close to new assets at ~$50MM FPAUM.

Nonetheless, Maury’s experiences in helping Bares reach initial critical mass are still very applicable to Askeladden, because that is what we are looking to reach. While he has worked in some other areas, small/micro–cap is not only his core expertise, but truly his passion. Maury understands the strategy, and understands the prospective clients to whom the strategy appeals. Maury understands that I focus on transparency and authenticity, and has not pushed me to be more “sales–y,” for lack of a better word.

Second, Maury, like me, is an entrepreneurial type with a “lean” mindset, not a large, stuffy company with a fancy office I have to pay for. He is a frugal Midwesterner who understands the value of my money. Unlike some firms that like to charge a huge retainer whether or not any capital is raised, with the exception of some reasonable / de minimis fees as we get started, Maury will get paid solely on commission.

He only benefits if he helps me find investors who are aligned with my philosophy (he knows I’m picky, that I’ve walked away from offered capital in the past, and am perfectly willing to do so in the future.) Maury, like Askeladden, focuses on quality over quantity and understands the benefits of concentration: he has worked with only a select handful of clients over time, and prefers building deep, long–term relationships with one (or maybe a few) that he believes in, rather than trying to represent all strategies to all people.

Third, and perhaps more importantly than the previous two, he understands the value of my time. Just as I occasionally speak to management teams or a company’s Investor Relations representative, sometimes multiple times, to understand nuances of the company’s strategy and results, so too I understand that part of my job is to answer questions from prospective clients.

In some cases, this interactive process is even beneficial for me; I learned a lot from a phone call several months ago with a family office that found our last letter online, and might consider investing in Askeladden. They are talented investors themselves and will probably (quite frankly) put up a better track record than I will over the long–term. I’ve had similar experiences with calls with some of our existing clients, especially those who are current or former professional investors themselves.

However, this interaction needs to be conducted in an efficient manner, with prospective clients already educated about the strategy, and much of the logistical setup / follow–up type work not on my plate, such that my interaction with any prospective client Maury sources is constrained to merely a few phone calls or meetings where I answer specific, targeted questions (with minimal travel.)

So far, in the two months we’ve been working together, my actual time contribution has been confined to merely a few days – most of which was one–time prep/setup work such as updating our pitchbook and obtaining and organizing various historical data, and the rest of which is a few hours (cumulatively less than one work day) for calls/meetings with prospective clients who have already been vetted as being aligned long–term investors with an interest in my particular strategy. This is extremely important to me, as my number one concern was remaining focused on research.

The nice thing is that Maury’s reach tend to be complementary to Askeladden’s, with only slight overlap to the kinds of investors who find me already. Individual investors, professional investors, and some family offices often tend to find me via my published work. I tend not to have as much reach with many family offices, small endowments, outsourced CIOs, and so on. These latter categories are the types of investors that Maury tends to have more reach with.

Retaining Maury allows me to access a new universe of potential clients in a low–risk way that doesn’t consume a lot of my time. Worst case, I spend a little bit of money, and a few hours a week, on calls with prospective clients that he sources, and I never raise any material capital – no harm, no foul. More likely, Maury will help us reach critical mass over the next few years, and can do so in a manner that minimizes my time commitment to marketing, allowing my focus to remain squarely where it should be: on the research that produces the results that clients are paying me their hard–earned money for.

In Conclusion

Since Askeladden is planning to close to new capital contributions at or before the $50MM mark in FPAUM, I will provide quarterly updates on FPAUM, as well as anticipated near–term additions to FPAUM, so that clients can plan accordingly if they wish to invest more capital in Askeladden before all capacity is taken.

To the extent possible, we would of course like to prioritize capacity existing clients who wish to add capital. We would also like to prioritize some capacity for our smaller accounts from early to mid–career professionals, including our friends/family clients, who may not have as much to invest now as our more well–heeled clients, but, like us, have a very long time horizon and are far less likely to need to reallocate capital elsewhere in the medium–term.

I admit to having a soft spot for this client type because – were I not the manager of Askeladden – it is exactly the sort of client I would be, myself. So whereas some managers don’t like the hassle of small accounts, Askeladden in fact sometimes make exceptions below our typical minimum for individuals in this category. Given my background, trying to help people who don’t already have a fortune achieve their long–term financial goals is naturally appealing, and investment options like Askeladden are not typically available to this type of investor – both because of minimum investment hurdles, and because many similar funds only offer a limited partnership that requires accreditation, whereas we offer SMAs that do not require accreditation.

However, we also cannot reserve capacity for an indefinite period of time if we have a lineup of philosophically aligned prospective clients who wish to invest in the near term. As such, to the extent possible, if you think you would like to add capital to Askeladden, I would encourage you to let me know – along with a rough date of when you think you would be able to add that capital – so I can be aware and keep that capacity open for you to the extent possible.

And if you know of anyone who might be a good fit for our process, please send them our way.

As always, thank you for your continued support. Managing part of your hard–earned capital is a responsibility I take very seriously, and I will continue to do my best to deliver superior results over time.

Westward on.

Samir