Starvine Capital Corporation 4Q17 Commentary

Overview

- Outlook: The Punisher’s View

- MCARV: More than an Acronym – A Checklist that Carves Between Winners & Duds

- Speculation: Why it (Almost) Always Results in Getting Creamed

Dear Starvine Capital Client:

In Q4 2017, accounts open and fully invested in the Starvine Flagship Strategy since the beginning of the quarter increased 9.4% to 9.5%, while the Mid-Large Cap Strategy increased 8.6%. During the quarter, the S&P TSX Total Return Index increased 4.5% and the S&P 500 Total Return Index increased 7.6% in Canadian dollars (+6.6% in USD). For the 2017 calendar year, Flagship increased 14.3% to 14.6%; Mid-Large Cap however was incepted in March of last year – and thus did not record a whole-year number.

While these numbers are strong on an absolute basis and relative to the Canadian index for 2017, they pale in comparison to the S&P for the full year. The largest single drag on performance was currency, as the US dollar declined 6.4% relative to the Canadian dollar during 2017. I estimate this had a ~4% net impact on Flagship due to the majority of holdings being denominated in US dollars. Various reports indicate that a small group of tech-related stocks – Facebook, Amazon, Netflix, and Google – were responsible for half the gains in the index.

Outlook

In Episode 8 of The Punisher, a series released on Netflix, there is a passage that is topical. Frank Castle, a.k.a. The Punisher, tries to intimidate a delinquent who procured a knife. Castle explains his preference for knives in close-quarters combat: “You see, with a gun, the target can get lucky. A bullet can miss what’s important. But not with this…” The rest is too graphic to reprint here, but the key point is that certain times call for specificity rather than a shot-gun approach. Whereas pressing a trigger introduces an element of randomness, the knife requires direct handling from start to finish.

And that brings us to the stock markets – the U.S. indexes are unquestionably expensive. If we liken the S&P 500 to a gun versus bottom-up stock picking as a knife, we can see that committing new funds to the S&P is precarious because one could be missing what is and what is always important – valuation. That is not to say bottom-up or active management cannot also miss what’s important, because that certainly is not true. In fact, active managers make mistakes all the time. However, if done well, the active manager is qualifying each stock selection rigorously and consciously weighing how its attributes fit with clients’ objectives. A typical value manager in this environment would (hypothetically) be leaning towards companies that have not fully joined in the chorus of the bull market, or better still companies that are temporarily out-of-favor. Recall that in value investing, the price paid for a security is always a critical component of the expected return. The same cannot be said for an index approach. The mainstream benchmarks are not rebalanced for valuation, as can be seen with the Cyclically Adjusted PE Ratio of the S&P 500, otherwise known as the Shiller PE Ratio.

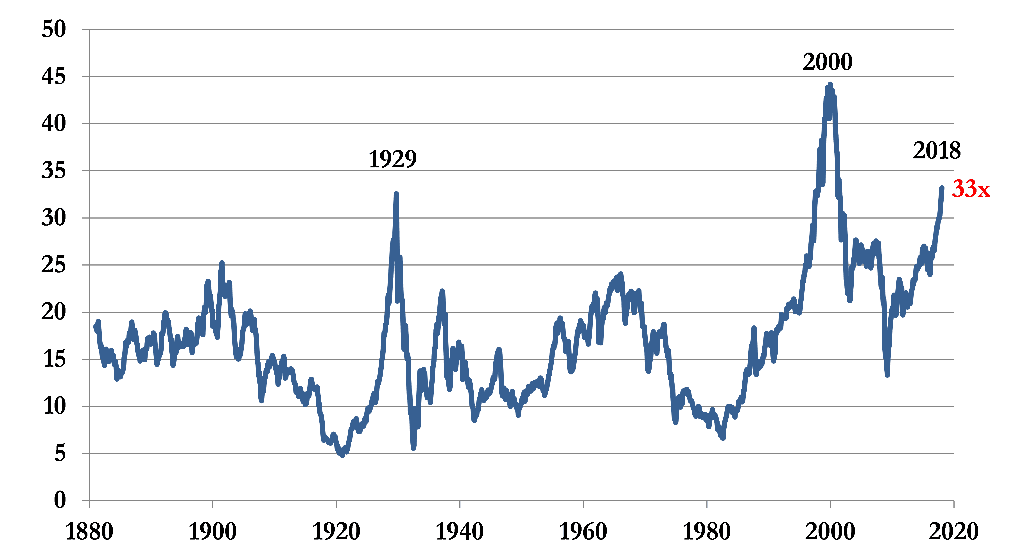

Shiller PE Ratio

Data courtesy of Robert Shiller (www.econ.yale.edu/~shiller/data.htm)

The Shiller PE Ratio smooths peaks and valleys by taking a trailing ten-year average of earnings. Currently hovering around 33x, the S&P has been more expensive on only two occasions in recorded history: immediately prior to the Great Crash of 1929 and the Tech Crash of 2000.

I have written previously about how gains in most situations can be attributed to a combination of earnings growth and multiple expansion. Paying a low multiple of earnings generally leaves potential to profit from market participants bidding up that multiple over time if the stock is mispriced. However, once the lever of multiple expansion is used up, further gains will depend mostly on increases in earnings. The same sort of logic should apply to the market as a whole. On that note, I estimate about 90% of the S&P’s gains over the past three years is attributable to multiple expansion.

I believe this bull market has gone on too long, and in too smooth a manner. Everything in this world has some element of cyclicality – everything. Being a contrarian, I would have a negative long-term outlook on equities if my field of vision was limited to the financial press and watching the movement of market indexes and blue chip stocks. Actually, I would go so far as to state that new investors committing fresh money into benchmark ETFs should think very carefully about whether their principal is protected, especially if their time horizon is less than ten years.

Seekers of value, on the other hand, are like snorkelers. Snorkelers can view only the wildlife directly beneath them with any clarity, one small area at a time. Certainly, the view may not reveal much from 20,000 feet above, but the time and money spent may be defensible from our bottom-up experiences within select pockets of the overall area.

And such is how I feel about the markets today. Equities appear (and may actually be) overextended in terms of being expensive – and priced to perfection – with only the argument that earnings yields still look attractive on a relative basis to long-term bonds. Even if that is the case and stocks face an uphill battle for the next few decades, my job is to find the ‘compounders’, those diamonds in the rough that will perform well because of their inherent strengths. The traits of quality and cheapness can happen in expensive markets – but it definitely requires that one is not limited to large capitalization (i.e. over $10 billion) companies, and moreover the investor must be open to deeply contrarian situations.

So I’m genuinely negative about equities in general because I believe they are loftily priced, yet I’m positive about the bottom-up opportunities that reside in the Starvine strategies. I know - no statement could be more self- serving! For DIY (do-it-yourself) investors, it is important to look soberly in the mirror and pose the following qualitative questions for each portfolio holding:

- Is the stock/company in question clearly undervalued?

- If not, are overall prospects exceptional enough to compensate for the lack of clear value? For example, does business quality, management track record, or growth runway offset a price that is not low enough?

If one can answer the above questions in the affirmative and without hesitation, much of the job of preserving capital in equities has been accomplished.

MCARV: More than an Acronym

Some quarters ago, I wrote about the sensibility of employing checklists in investing. Since then, I have been thinking about how to screen investment candidates in in the initial stages so as to effectively narrow the universe according to my requirements. There is always a compromise in using this approach: investments that have a higher probability of failure will be filtered out, but at the risk of missing enormous opportunities that don’t make it through the screens. What I arrived at was a short list of characteristics I would require in any long-term investment: M.C.A.R.V.

- Moats

- Capital Allocation

- Reinvestment Runway

- Valuation

Let us briefly walk through each requirement.

- Moats: These are characteristics that allow a business to enjoy above average profits over a long time period despite the constant efforts of competition. Without moats, we would have little confidence that a company’s current earnings power will have longevity.

- Capital Allocation: This is the act of deploying and reinvesting cash resources to grow the value of a corporation. For a public company, there are only five basic levers in the toolbox: investment in organic growth, acquisitions, debt reduction, issuing dividends, and share buybacks. It is uncommon to find management teams who have a long and successful track record of intelligently allocating capital.

- Reinvestment Runway: If a company has moats and an intelligent capital allocator aboard, that isn’t sufficient. The company needs a runway of opportunities to redeploy earnings, and at a high enough rate of return, to grow its cash flow generation. Without this ingredient, it will be difficult for a self-sufficient business to provide adequate growth over the long run.

- Valuation: Price is an all-critical input for any investment. Now that we have identified a strong business (moats), run by managers who are likely to re-invest earnings intelligently (capital allocation), and with ample opportunity to re-invest said earnings, we must decide on a price at or under which the idea will provide a compelling return. As value investors, we aim to underpay in order to create a form of downside protection, while simultaneously setting up a situation that has favorable odds of success.

My conviction is that an investor increases the chance of winning (in the long-term) and reduces the likelihood of permanent loss if the above list can be satisfied. In other words, if one can quickly identify the above attributes in a stock idea, the chances are good that a high-quality investment has been landed upon. Because the first three requirements are qualitative, it would be next to impossible to mechanically screen through a large population and capture the best opportunities.

Think of any investment blow up you’ve had over the years; did any of them contain all four of the attributes named above?

Speculation: When Making a Gain is Deleterious to One’s Health

No statistics are required to prove this point: the worst thing that can happen to a gambler is to win big. Why is that? Is it not always a good thing to make money?

I would proffer that people are better served by losing in speculation, sooner rather than later. That’s right - the speculator who lost money in the tech crash of 2000 was better served by his misfortune than the one who sold out on time. If one happens to be in the outer stages of life and wins a big gamble, there isn’t much time to quash the gains. However, should one have decades remaining, being turbo-charged by false confidence - and moreover not being aware of it – can be the complete undoing of one’s financial condition.

Most winners from gambles in bitcoin or pot stocks have no clue how to read financial statements and little knowledge otherwise about investing. They felt a sense of urgency to act after witnessing the instant profits enjoyed by peers. And then a gain was made! Investing isn’t as hard as it sounds, they think. This is why the feedback loop of winning in gambling is so toxic:

- Was only one percent of net worth committed in the bet? Great – it went up multiples in short order and now represents five percent of the portfolio. If only a larger sum was originally invested. Why not commit five percent next time? Ten percent? Fifteen percent? Fifty percent? Next time – and there will always be a next time – it will be tempting to bet a much larger proportion of the pot.

- Was an enormous portion of savings invested before the big win? Yes. It is now clear that financial independence has been achieved. But will a sensible and methodical approach now become habit? Very unlikely. The thrill of being “right” and making easy money will wrestle with one’s mind; the subconscious will command a return to the quick gratification. The money was so immediate and easy last time, and so it may be the next time as well.

And so the cycle repeats until the inevitable blow up.

Sector Breakdown

| Flagship | Mid-Large Cap | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

Starvine uses a decision making system that prioritizes absolute returns. Even in this environment, my research is showing most of the existing portfolio incumbents to be compelling opportunities. It is encouraging to see some ideas, especially those in healthcare, begin to pay off. Meanwhile, there are several ideas in each strategy that haven’t been “working out”, as in their prices have been lagging the growth in value as I see it.

The indexes continue to inch higher in the backdrop to valuations that are far from attractive; being fully invested in lofty times should be a source of anxiety, and perhaps a reconsideration of minimum cash levels is warranted.

Sincerely,

Steven Ko

Portfolio Manager