By MasterClassInvest

Many inferences have been drawn over time between the Market and Business. This is nothing new to any of us and we have seen it often. The analogies are always simple, clean and relevant and offer practical value to our investing activities. At the same time, many of the Investment Masters have espoused the value in not only being capable in both arenas, but also in keeping up to date on your knowledge of both. It makes sense right? Sure it does.

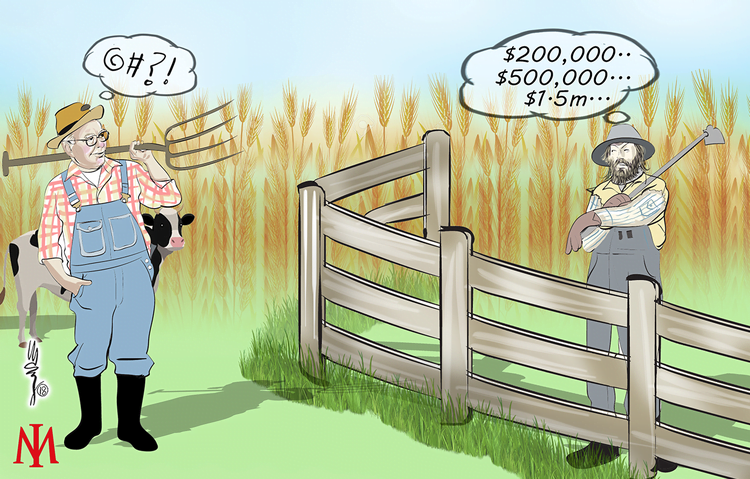

But there are also other comparisons out there, ones which might not be as obvious at first glance. If I told you there was also value to be gained from comparing Investing to Farming, what would you say?

Hopefully you would agree with me.

Good ol' farming. It's been there forever, through good times and bad. And the inferences that can be drawn between it and Investing are many.

Let's start with those good and bad times, because they happen to all of us whether you are digging in the dirt or investing in the market. The last two weeks drop in global markets is solid enough evidence of that, as is the freakish weather conditions in different parts of the world that have had a negative impact on the farming sector. The actual lesson though lies in how we react to the market tanking or when a farmer's crops fail.

In situations like we have just witnessed in the market, prices dropped and investors rushed to get out, causing a significant level of volatility. But every farmer expects the unexpected and recognises that despite his best efforts, nature doesn't always deliver optimal outcomes - pests descend, rains don't come, commodity prices fall.

But if we were working a farm and had one bad year because of say, adverse weather conditions, would you immediately cut the value of your farm in half? Of course not. The value of the farm is the future value of many many years of crops, one bad season just doesn't have that much impact. In contrast, the stock market often over reacts to poor earnings and slashes good companies prices when the unexpected happens.

“You would not cut the value of a good farm in half just because bad weather conditions caused a crop failure in a single year” Phil Fisher

Farmers exhibit patience. They hold onto good farm property even when they have a bad crop. Farmers don't and aren't expected to trade their paddocks and no-one raises eyebrows when they don't.

"No reasonable person would expect a farmer to sell his farm in order to buy a different farm every decade, let alone every year or several times a year. As public-market investors, however, this "sitting on our hands" behaviour is unusual." Clifford Sosin

And the value of farm land remains pretty constant. The absence of minute by minute pricing for farmers to obsess over means farmers tend to set prices by analysing what the farm will earn over a long period of time. Contrast that to stock prices which tend to be set by the whim of the most emotional participant watching the constant gyrations of the market. That's a gift for the rational investor.

“Stocks provide you minute-to-minute valuations for your holdings whereas I have yet to see a quotation for either my farm or the New York real estate. It should be an enormous advantage for investors in stocks to have those wildly fluctuating valuations placed on their holdings – and for some investors, it is. After all, if a moody fellow with a farm bordering my property yelled out a price every day to me at which he would either buy my farm or sell me his – and those prices varied widely over short periods of time depending on his mental state – how in the world could I be other than benefited by his erratic behaviour? If his daily shout-out was ridiculously low, and I had some spare cash, I would buy his farm. If the number he yelled was absurdly high, I could either sell to him or just go on farming.” Warren Buffett

Stock prices go up or down responding to any number of psychological biases as opposed to fundamental developments. Yet, while those prices change, they generally don't impact what a company will earn.

“If Investors' frenetically bought and sold farmland to each other, neither the yields nor prices of their crops would be increased. The only consequence of such behaviour would be decreases in the overall earnings realized by the farm-owning population because of the substantial costs it would incur as it sought advice and switched properties.” Warren Buffett

And farmers don't respond to what other farmers are doing like investors do. If a farm a few paddocks away sells for less than the farmer paid, he's not going to rush to sell his property too.

"Instead of focusing on what businesses will do in the years ahead, many prestigious

money managers now focus on what they expect other money managers to do in the days ahead. For them, stocks are merely tokens in a game, like the thimble and flatiron in Monopoly.... an extreme example of what their attitude leads to is "portfolio insurance," a money-management strategy that many leading investment advisors embraced in 1986-1987 ... After buying a farm, would a rational owner next order his real estate agent to start selling off pieces of it whenever a neighbouring property was sold at a lower price? Or would you sell your house to whatever bidder was available at 9:31 on some morning merely

because at 9:30 a similar house sold for less than it would have brought on the previous day?" Warren Buffett 1987

Per the lessons gained from the Fingers of Instability posts, learning from this farming analogy is just as important. We know that many investors react to market conditions without really knowing or understanding the intrinsic worth of the stocks they hold. Farming is a long term game and investing should be considered the same way. We should not expect great yields every year from either, rather sometimes we can expect to have to 'weather a storm', and in doing so we can expect a bumper crop.