Kerrisdale Capital is short shares of Camber Energy Inc (NYSEAMERICAN:CEI). Camber is a defunct oil producer that has failed to file financial statements with the SEC since September 2020, is in danger of having its stock delisted next month, and just fired its accounting firm in September. Its only real asset is a 73% stake in Viking Energy Group Inc (OTCMKTS:VKIN), an OTC-traded company with negative book value and a going-concern warning that recently violated the maximum-leverage covenant on one of its loans. (For a time, it also had a fake CFO – long story.) Nonetheless, Camber’s stock price has increased by 6x over the past month; last week, astonishingly, an average of $1.9 billion worth of Camber shares changed hands every day.

Q2 2021 hedge fund letters, conferences and more

Is there any logic to this bizarre frenzy? Camber pumpers have seized upon the notion that the company is now a play on carbon capture and clean energy, citing a license agreement recently entered into by Viking. But the “ESG Clean Energy” technology license is a joke. Not only is it tiny relative to Camber’s market cap (costing only $5 million and granting exclusivity only in Canada), but it has embroiled Camber in the long-running escapades of a western Massachusetts family that once claimed to have created a revolutionary new combustion engine, only to wind up being penalized by the SEC for raising $80 million in unregistered securities offerings, often to unaccredited investors, and spending much of it on themselves.

But the most fascinating part of the CEI boondoggle actually has to do with something far more basic: how many shares are there, and why has dilution been spiraling out of control? We believe the market is badly mistaken about Camber’s share count and ignorant of its terrifying capital structure. In fact, we estimate its fully diluted share count is roughly triple the widely reported number, bringing its true, fully diluted market cap, absurdly, to nearly $900 million.

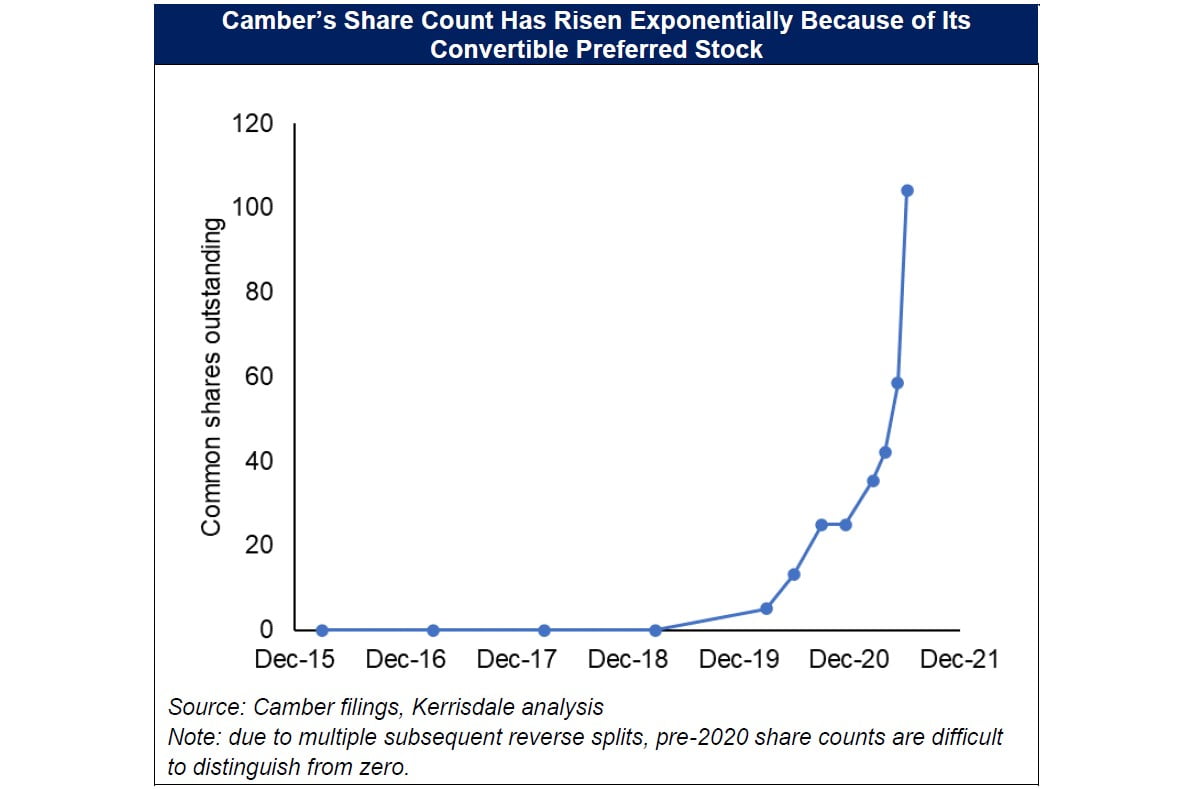

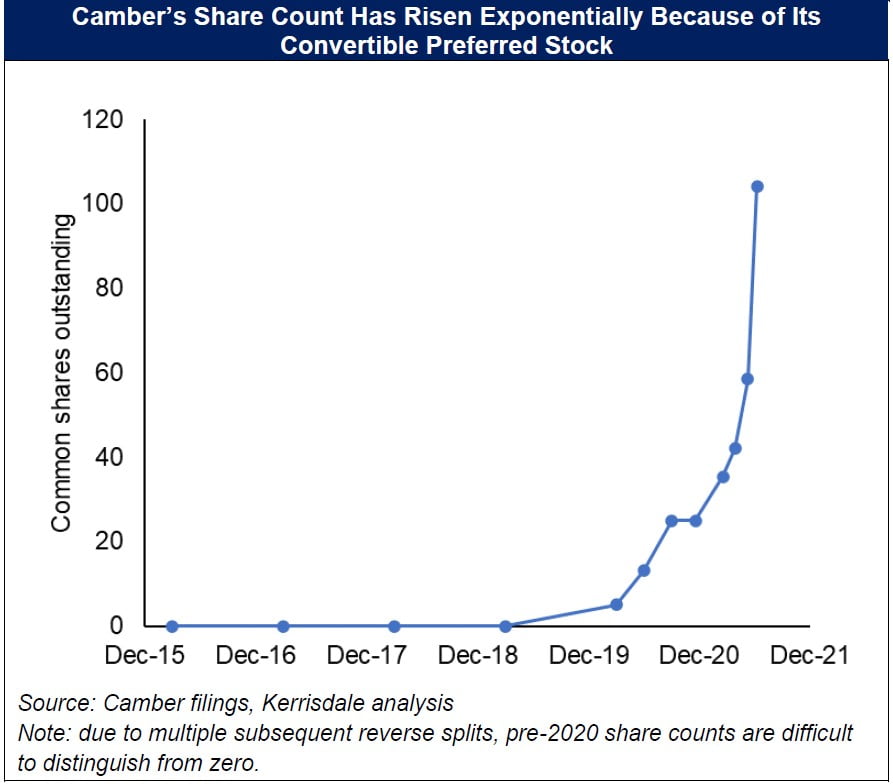

Since Camber is delinquent on its financials, investors have failed to fully appreciate the impact of its ongoing issuance of an unusual, highly dilutive class of convertible preferred stock. As a result of this “death spiral” preferred, Camber has already seen its share count increase 50- million-fold from early 2016 to July 2021 – and we believe it isn’t over yet, as preferred holders can and will continue to convert their securities and sell the resulting common shares.

Even at the much lower valuation that investors incorrectly think Camber trades for, it’s still overvalued. The core Viking assets are low-quality and dangerously levered, while any near- term benefits from higher commodity prices will be muted by hedges established in 2020. The recent clean-energy license is nearly worthless. It’s ridiculous to have to say this, but Camber isn’t worth $900 million. If it looks like a penny stock, and it acts like a penny stock, it is a penny stock. Camber has been a penny stock before – no more than a month ago, in fact – and we expect that it will be once again.

Company Background

Founded in 2004, Camber was originally called Lucas Energy Resources. It went public via a reverse merger in 2006 with the plan of “capitaliz[ing] on the increasing availability of opportunistic acquisitions in the energy sector.”1 But after years of bad investments and a nearly 100% decline in its stock price, the company, which renamed itself Camber in 2017, found itself with little economic value left; faced with the prospect of losing its NYSE American listing, it cast about for new acquisitions beginning in early 2019. That’s when Viking entered the picture. Jim Miller, a member of Camber’s board, had served on the board of a micro-cap company called Guardian 8 that was working on “a proprietary new class of enhanced non-lethal weapons”; Guardian 8’s CEO, Steve Cochennet, happened to also be part owner of a Kansas-based company that operated some of Viking’s oil and gas assets and knew that Viking, whose shares traded over the counter, was interested in moving up to a national exchange.2 (In case you’re wondering, under Miller and Cochennet’s watch, Guardian 8’s stock saw its price drop to ~$0; it was delisted in 2019.3)

Viking itself also had a checkered past. Previously a shell company, it was repurposed by a corporate lawyer and investment banker named Tom Simeo to create SinoCubate, “an incubator of and investor in privately held companies mainly in P.R. China.” But this business model went nowhere. In 2012, SinoCubate changed its name to Viking Investments but continued to achieve little. In 2014, Simeo brought in James A. Doris, a Canadian lawyer, as a member of the board of directors and then as president and CEO, tasked with executing on Viking’s new strategy of “acquir[ing] income-producing assets throughout North America in various sectors, including energy and real estate.” In a series of transactions, Doris gradually built up a portfolio of oil wells and other energy assets in the United States, relying on large amounts of high-cost debt to get deals done. But Viking has never achieved consistent GAAP profitability; indeed, under Doris’s leadership, from 2015 to the first half of 2021, Viking’s cumulative net income has totaled negative $105 million, and its financial statements warn of “substantial doubt regarding the Company’s ability to continue as a going concern.”4

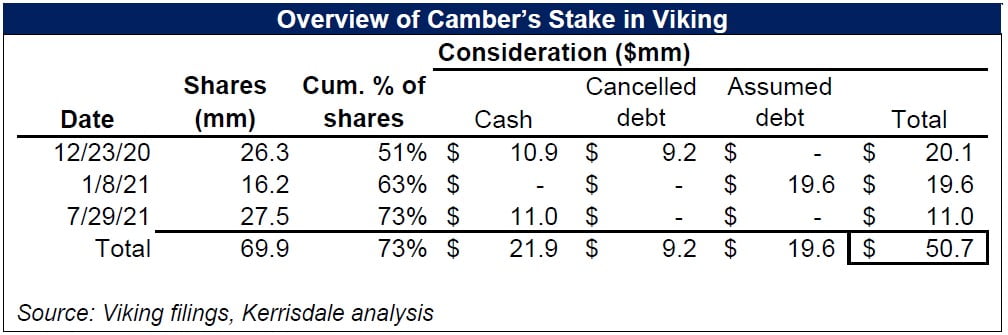

At first, despite the Guardian 8 crew’s match-making, Camber showed little interest in Viking and pursued another acquisition instead. But, when that deal fell apart, Camber re-engaged with Viking and, in February 2020, announced an all-stock acquisition – effectively a reverse merger in which Viking would end up as the surviving company but transfer some value to incumbent Camber shareholders in exchange for the national listing. For reasons that remain somewhat unclear, this original deal structure was beset with delays, and in December 2020 (after months of insisting that deal closing was just around the corner) Camber announced that it would instead directly purchase a 51% stake in Viking; at the same time, Doris, Viking’s CEO, officially took over Camber as well. Subsequent transactions through July 2021 have brough Camber’s Viking stake up to 69.9 million shares (73% of Viking’s total common shares), in exchange for consideration in the form of a mixture of cash, debt forgiveness,5 and debt assumption, valued in the aggregate by Viking at only $50.7 million:

Camber and Viking announced a new merger agreement in February 2021, aiming to take out the remaining Viking shares not owned by Camber and thus fully combine the two companies, but that plan is on hold because Camber has failed to file its last 10-K (as well as two subsequent 10-Qs) and is thus in danger of being delisted unless it catches up by November. Today, then, Camber’s absurd equity valuation rests entirely on its majority stake in a small, unprofitable oil-and-gas roll-up cobbled together by a Canadian lawyer.

An Opaque Capital Structure Has Concealed the True Insanity of Camber’s Valuation

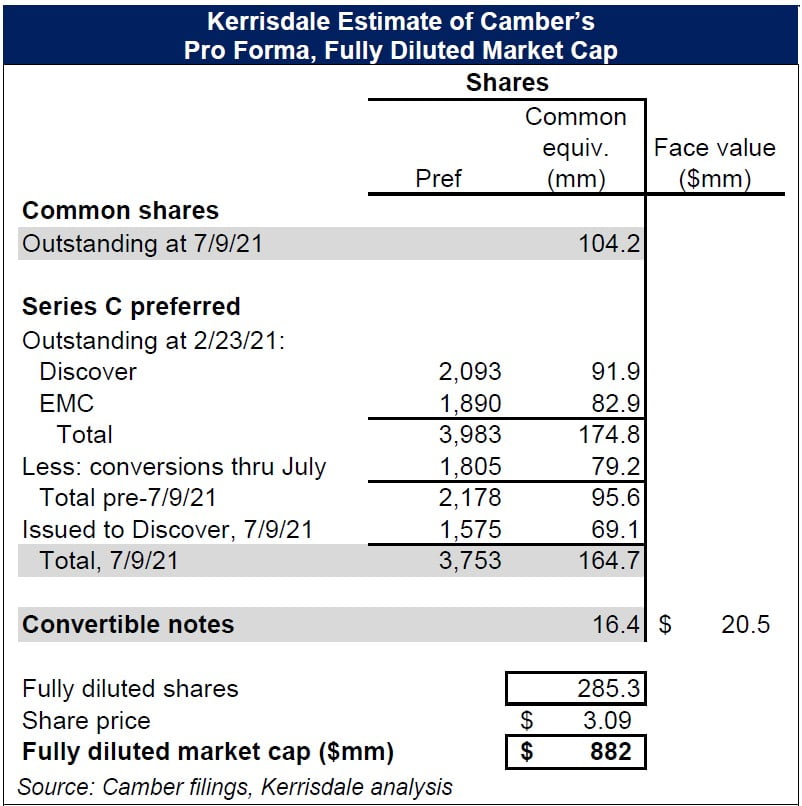

What actually is Camber’s equity valuation? It sounds like a simple question, and sources like Bloomberg and Yahoo Finance supply what looks like a simple answer: 104.2 million shares outstanding times a $3.09 closing price (as of October 4, 2021) equals a market cap of $322 million – absurd enough, given what Camber owns. But these figures only tell part of the story. We estimate that the correct fully diluted market cap is actually a staggering $882 million, including the impact of both Camber’s unusual, highly dilutive Series C convertible preferred stock and its convertible debt.

Because Camber is delinquent on its SEC filings, it’s difficult to assemble an up-to-date picture of its balance sheet and capital structure. The widely used 104.2-million-share figure comes from an 8-K filed in July that states, in part:

As of July 9, 2021, the Company had 104,195,295 shares of common stock issued and outstanding. The increase in our outstanding shares of common stock from the date of the Company’s February 23, 2021 increase in authorized shares of common stock (from 25 million shares to 250 million shares), is primarily due to conversions of shares of Series C Preferred Stock of the Company into common stock, and conversion premiums due thereon, which are payable in shares of common stock.

This bland language belies the stunning magnitude of the dilution that has already taken place. Indeed, we estimate that, of the 104.2 million common shares outstanding on July 9th, 99.7% were created via the conversion of Series C preferred in the past few years – and there’s more where that came from.

The terms of Camber’s preferreds are complex but boil down to the following: they accrue non- cash dividends at the sky-high rate of 24.95% per year for a notional seven years but can be converted into common shares at any time. The face value of the preferred shares converts into common shares at a fixed conversion price of $162.50 per share, far higher than the current trading price – so far, so good (from a Camber-shareholder perspective). The problem is the additional “conversion premium,” which is equal to the full seven years’ worth of dividends, or 7 x 24.95% ≈ 175% of face value, all at once, and is converted at a far lower conversion price that “will never be above approximately $0.3985 per share…regardless of the actual trading price of

Camber’s common stock” (but could in principle go lower if the price crashes to new lows).6 The upshot of all this is that one share of Series C preferred is now convertible into ~43,885 shares of common stock.7

Historically, all of Camber’s Series C preferred was held by one investor: Discover Growth Fund. The terms of the preferred agreement cap Discover’s ownership of Camber’s common shares at 9.99% of the total, but nothing stops Discover from converting preferred into common up to that cap, selling off the resulting shares, converting additional preferred shares into common up to the cap, selling those common shares, etc., as Camber has stated explicitly (and as Discover has in fact done over the years) (emphasis added):

Although Discover may not receive shares of common stock exceeding 9.99% of its outstanding shares of common stock immediately after affecting such conversion, this restriction does not prevent Discover from receiving shares up to the 9.99% limit, selling those shares, and then receiving the rest of the shares it is due, in one or more tranches, while still staying below the 9.99% limit. If Discover chooses to do this, it will cause substantial dilution to the then holders of its common stock. Additionally, the continued sale of shares issuable upon successive conversions will likely create significant downward pressure on the price of its common stock as Discover sells material amounts of Camber’s common stock over time and/or in a short period of time. This could place further downward pressure on the price of its common stock and in turn result in Discover receiving an ever increasing number of additional shares of common stock upon conversion of its securities, and adjustments thereof, which in turn will likely lead to further dilution, reductions in the exercise/conversion price of Discover’s securities and even more downward pressure on its common stock, which could lead to its common stock becoming devalued or worthless.8

In 2017, soon after Discover began to convert some of its first preferred shares, Camber’s then- management claimed to be shocked by the results and sued Discover for fraud, arguing that “[t]he catastrophic effect of the Discover Documents [i.e. the terms of the preferred] is so devastating that the Discover Documents are prima facie unconscionable” because “they will permit Discover to strip Camber of its value and business well beyond the simple repayment of its debt.” Camber called the documents “extremely difficult to understand” and insisted that they “were drafted in such a way as to obscure the true terms of such documents and the total number of shares of common stock that could be issuable by Camber thereunder. … Only after signing the documents did Camber and [its then CEO]…learn that Discover’s reading of the Discover Documents was that the terms that applied were the strictest and most Camber unfriendly interpretation possible.”9 But the judge wasn’t impressed, suggesting that it was Camber’s own fault for failing to read the fine print, and the case was dismissed. With no better options, Camber then repeatedly came crawling back to Discover for additional tranches of funding via preferred sales.

While the recent spike in common share count to 104.2 million as of early July includes some of the impact of ongoing preferred conversion, we believe it fails to include all of it. In addition to Discover’s 2,093 shares of Series C preferred held as of February 2021, Camber issued additional shares to EMC Capital Partners, a creditor of Viking’s, as part of a January agreement to reduce Viking’s debt.10 Then, in July, Camber issued another block of preferred shares – also to Discover, we believe – to help fund Viking’s recent deals.11 We speculate that many of these preferred shares have already been converted into common shares that have subsequently been sold into a frenzied retail bid.

Beyond the Series C preferred, there is one additional source of potential dilution: debt issued to Discover in three transactions from December 2020 to April 2021, totaling $20.5 million in face value, and amended in July to be convertible at a fixed price of $1.25 per share.12 We summarize our estimates of all of these sources of potential common share issuance below:

Might we be wrong about this math? Absolutely – the mechanics of the Series C preferreds are so convoluted that prior Camber management sued Discover complaining that the legal documents governing them “were drafted in such a way as to obscure the true terms of such documents and the total number of shares of common stock that could be issuable by Camber thereunder.” Camber management could easily set the record straight by revealing the most up- to-date share count via an SEC filing, along with any additional clarifications about the expected future share count upon conversion of all outstanding convertible securities. But we're confident that the current share count reported in financial databases like Bloomberg and Yahoo Finance significantly understates the true, fully diluted figure.

An additional indication that Camber expects massive future dilution relates to the total authorized shares of common stock under its official articles of incorporation. It was only a few months ago, in February, that Camber had to hold a special shareholder meeting to increase its maximum authorized share count from 25 million to 250 million in order to accommodate all the shares to be issued because of preferred conversions. But under Camber’s July agreement to sell additional preferred shares to Discover, the company (emphasis added)

agreed to include proposals relating to the approval of the July 2021 Purchase Agreement and the issuance of the shares of common stock upon conversion of the Series C Preferred Stock sold pursuant to the July 2021 Purchase Agreement, as well as an increase in authorized common stock to fulfill our obligations to issue such shares, at the Company’s next Annual Meeting, the meeting held to approve the Merger or a separate meeting in the event the Merger is terminated prior to shareholder approval, and to use commercially reasonable best efforts to obtain such approvals as soon as possible and in any event prior to January 1, 2022.13

In other words, Camber can already see that 250 million shares will soon not be enough, consistent with our estimate of ~285 million fully diluted shares above.

In sum, Camber’s true overvaluation is dramatically worse than it initially appears because of the massive number of common shares that its preferred and other securities can convert into, leading to a fully diluted share count that is nearly triple the figure found in standard information sources used by investors. This enormous latent dilution, impossible to discern without combing through numerous scattered filings made by a company with no up-to-date financial statements in the public domain, means that the market is – perhaps out of ignorance – attributing close to one billion dollars of value to a very weak business.

Camber’s Stake in Viking Has Little Real Value

In light of Camber’s gargantuan valuation, it’s worth dwelling on some basic facts about its sole meaningful asset, a 73% stake in Viking Energy. As of 6/30/21:

- Viking had negative $15 million in shareholder equity/book

- Its financial statements noted “substantial doubt regarding the Company’s ability to continue as a going ”

- Of its $101.3 million in outstanding debt (at face value), nearly half (48%) was scheduled to mature and come due over the following 12 months.

- Viking noted that it “does not currently maintain controls and procedures that are designed to ensure that information required to be disclosed by the Company in the reports it files or submits under the Exchange Act are recorded, processed, summarized, and reported within the time periods specified by the Commission’s rules and forms.” Viking’s CEO “has concluded that these [disclosure] controls and procedures are not effective in providing reasonable assurance of compliance.”

- Viking disclosed that a key subsidiary, Elysium Energy, was “in default of the maximum leverage ratio covenant under the term loan agreement at June 30, 2021”; this covenant caps the entity’s total secured debt to EBITDA at 75 to 1.14

This is hardly a healthy operation. Indeed, even according to Viking’s own black-box estimates, the present value of its total proved reserves of oil and gas, using a 10% discount rate (likely generous given the company’s high debt costs), was $120 million as of 12/31/20,15 while its outstanding debt, as stated above, is $101 million – perhaps implying a sliver of residual economic value to equity holders, but not much. And while some market observers have recently gotten excited about how increases in commodity prices could benefit Camber/Viking, any near-term impact will be blunted by hedges put on by Viking in early 2020, which cover, with respect to its Elysium properties, “60% of the estimated production for 2021 and 50% of the estimated production for the period between January, 2022 to July, 2022. Theses hedges have a floor of $45 and a ceiling ranging from $52.70 to $56.00 for oil, and a floor of $2.00 and a ceiling of $2.425 for natural gas” – cutting into the benefit of any price spikes above those ceiling levels.16

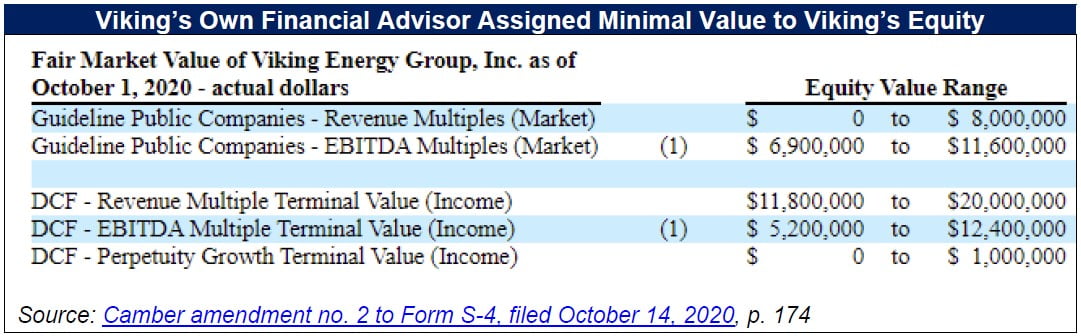

Sharing our dreary view of Viking’s prospects is one of Viking’s own financial advisors, a firm called Scalar, LLC, that Viking hired to prepare a fairness opinion under the original all-stock merger agreement with Camber. Combining Viking’s own internal projections with data on comparable-company valuation multiples, Scalar concluded in October 2020 that Viking’s equity was worth somewhere between $0 and $20 million, depending on the methodology used, with the “purest” methodology – a true, full-blown DCF – yielding the lowest estimate of $0-1 million:

Camber’s advisor, Mercer Capital, came to a similar conclusion: its “analysis indicated an implied equity value of Viking of $0 to $34.3 million.”17 It’s inconceivable that a majority stake in this company, deemed potentially worthless by multiple experts and clearly experiencing financial strains, could somehow justify a near-billion-dollar valuation.

Instead of dwelling on the unpleasant realities of Viking’s oil and gas business, Camber has drawn investor attention to two recent transactions conducted by Viking with Camber funding: a license agreement with “ESG Clean Energy,” discussed in further detail below, and the acquisition of a 60.3% stake in Simson-Maxwell, described as “a leading manufacturer and supplier of industrial engines, power generation products, services and custom energy solutions.” But Viking paid just $8 million for its Simson-Maxwell shares,18 and the company has just 125 employees; it defies belief to think that this purchase was such a bargain as to make a material dent in Camber’s overvaluation.

And what does Simson-Maxwell actually do? One of its key officers, Daryl Kruper (identified as its chairman in Camber’s press release), describes the company a bit less grandly and more concretely on his LinkedIn page:

Simson Maxwell is a power systems specialist. The company assembles and sells generator sets, industrial engines, power control systems and switchgear. Simson Maxwell has service and parts facilities in Edmonton, Calgary, Prince George, Vancouver, Nanaimo and Terrace. The company has provided its western Canadian customers with exceptional service for over 70 years.

In other words, Simson-Maxwell acts as a sort of distributor/consultant, packaging industrial- strength generators and engines manufactured by companies like GE and Mitsubishi into systems that can provide electrical power, often in remote areas in western Canada; Simson- Maxwell employees then drive around in vans maintaining and repairing these systems. There’s nothing obviously wrong with this business, but it’s small, regional (not just Canada – western Canada specifically), likely driven by an unpredictable flow of new large projects, and unlikely to garner a high standalone valuation. Indeed, buried in one of Viking’s agreements with Simson- Maxwell’s selling shareholders (see p. 23) are clauses giving Viking the right to purchase the rest of the company between July 2024 and July 2026 at a price of at least 8x trailing EBITDA and giving the selling shareholders the right to sell the rest of their shares during the same time frame at a price of at least 7x trailing EBITDA – the kind of multiples associated with sleepy industrial distributors, not fast-growing retail darlings.

Since Simon-Maxwell has nothing to do with Viking’s pre-existing assets or (alleged) expertise in oil and gas, and Viking and Camber are hardly flush with cash, why did they make the purchase? We speculate that management is concerned about the combined company’s ability to maintain its listing on the NYSE American. For example, when describing its restruck merger agreement with Viking, Camber noted:

Additional closing conditions to the Merger include that in the event the NYSE American determines that the Merger constitutes, or will constitute, a “back-door listing”/“reverse merger”, Camber (and its common stock) is required to qualify for initial listing on the NYSE American, pursuant to the applicable guidance and requirements of the NYSE as of the Effective Time.

What does it take to qualify for initial listing on the NYSE American? There are several ways, but three require at least $4 million of positive stockholders’ equity, which Viking, the intended surviving company, doesn’t have today; another requires a market cap of greater than $75 million, which management might (quite reasonably) be concerned about achieving sustainably. That leaves a standard that requires a listed company to have $75 million in assets and revenue. With Viking running at only ~$40 million of annualized revenue, we believe management is attempting to buy up more via acquisition. In fact, if the goal is simply to “buy” GAAP revenue, the most efficient way to do it is by acquiring a stake in a low-margin, slow- growing business – little earnings power, hence a low purchase price, but plenty of revenue. And by buying a majority stake instead of the whole thing, the acquirer can further reduce the capital outlay while still being able to consolidate all of the operation’s revenue under GAAP accounting. Buying 60.3% of Simson-Maxwell seems to fit the bill, but it’s a placeholder, not a real value-creator.

Camber’s Partners in the Laughable “ESG Clean Energy” Deal Have a Long History of Broken Promises and Alleged Securities Fraud

The “catalyst” most commonly cited by Camber Energy bulls for the recent massive increase in the company’s stock price is an August 24th press release, “Camber Energy Secures Exclusive IP License for Patented Carbon-Capture System,” announcing that the company, via Viking, “entered into an Exclusive Intellectual Property License Agreement with ESG Clean Energy, LLC (‘ESG’) regarding ESG’s patent rights and know-how related to stationary electric power generation, including methods to utilize heat and capture carbon dioxide.” Our research suggests that the “intellectual property” in question amounts to very little: in essence, the concept of collecting the exhaust gases emitted by a natural-gas–fueled electric generator, cooling it down to distill out the water vapor, and isolating the remaining carbon dioxide. But what happens to the carbon dioxide then? The clearest answer ESG Clean Energy has given is that it “can be sold to…cannabis producers”19 to help their plants grow faster, though the vast majority of the carbon dioxide would still end up escaping into the atmosphere over time, and additional greenhouse gases would be generated in compressing and shipping this carbon dioxide to the cannabis producers, likely leading to a net worsening of carbon emissions.20

And what is Viking – which primarily extracts oil and gas from the ground, as opposed to running generators and selling electrical power – supposed to do with this technology anyway? The idea seems to be that the newly acquired Simson-Maxwell business will attempt to sell the “technology” as a value-add to customers who are buying generators in western Canada. Indeed, while Camber’s press-release headline emphasized the “exclusive” nature of the license, the license is only exclusive in Canada plus “up to twenty-five locations in the United States” – making the much vaunted deal even more trivial than it might first appear.

Viking paid an upfront royalty of $1.5 million in cash in August, with additional installments of $1.5 and $2 million due by January and April 2022, respectively, for a total of $5 million. In addition, Viking “shall pay to ESG continuing royalties of not more than 15% of the net revenues of Viking generated using the Intellectual Property, with the continuing royalty percentage to be jointly determined by the parties collaboratively based on the parties’ development of realistic cashflow models resulting from initial projects utilizing the Intellectual Property, and with the parties utilizing mediation if they cannot jointly agree to the continuing royalty percentage”21 – a strangely open-ended, perhaps rushed, way of setting a royalty rate.

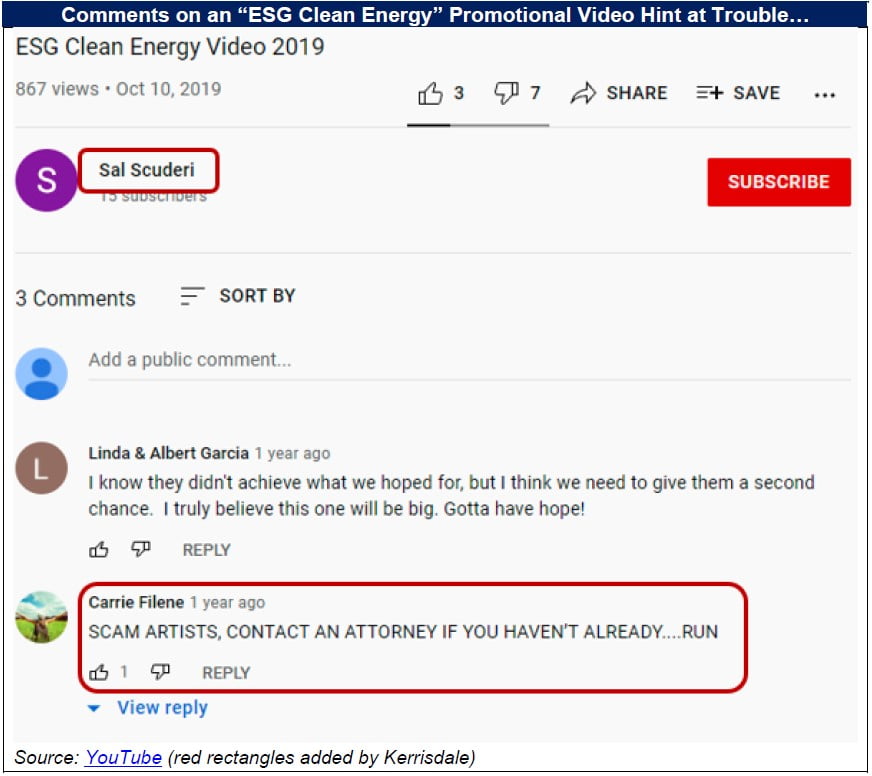

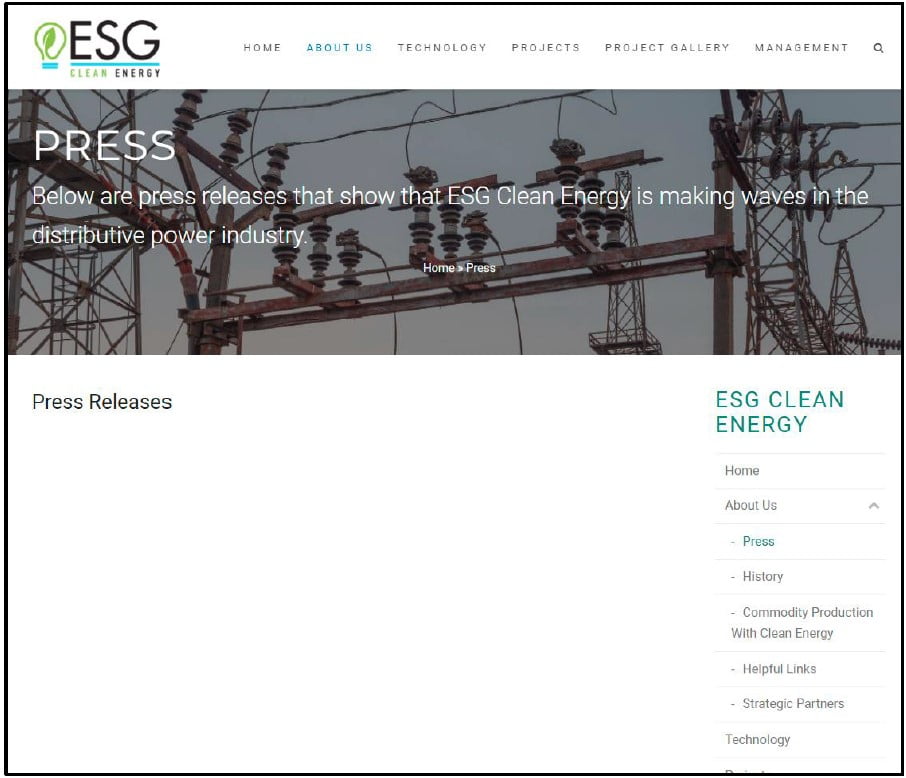

Overall, then, Viking is paying $5 million for roughly 85% of the economics of a technology that might conceivably help “capture” CO2 emitted by electric generators in Canada (and up to 25 locations in the United States!) but then probably just re-emit it again. This is the great advance that has driven Camber to a nearly billion-dollar market cap. It’s with good reason that on ESG Clean Energy’s web site (as of early October), the list of “press releases that show that ESG Clean Energy is making waves in the distributive power industry” is blank:

If the ESG Clean Energy license deal were just another trivial bit of vaporware hyped up by a promotional company and its over-eager shareholders, it would be problematic but unremarkable; things like that happen all the time. But it’s the nature and history of Camber/Viking’s counterparty in the ESG deal that truly makes the situation sublime.

ESG Clean Energy is in fact an offshoot of the Scuderi Group, a family business in western Massachusetts created to develop the now deceased Carmelo Scuderi’s idea for a revolutionary new type of engine. (In a 2005 AP article entitled “Engine design draws skepticism,” an MIT professor “said the creation is almost certain to fail.”) Two of Carmelo’s children, Nick and Sal, appeared in a recent ESG Clean Energy video with Camber’s CEO, who called Sal “more of the brains behind the operation” but didn’t state his official role – interesting since documents associated with ESG Clean Energy’s recent small-scale capital raises don’t mention Sal at all. Buried in Viking’s contract with ESG Clean Energy is the following section, indicating that the patents and technology underlying the deal actually belong in the first instance to the Scuderi Group, Inc.:

2.6 Demonstration of ESG’s Exclusive License with Scuderi Group and Right to Grant Licenses in this Agreement. ESG shall provide necessary documentation to Viking which demonstrates ESG’s right to grant the licenses in this Section 2 of this Agreement. For the avoidance of doubt, ESG shall provide necessary documentation that verifies the terms and conditions of ESG’s exclusive license with the Scuderi Group, Inc., a Delaware USA corporation, having an address of 1111 Elm Street, Suite 33, West Springfield, MA 01089 USA (“Scuderi Group”), and that nothing within ESG’s exclusive license with the Scuderi Group is inconsistent with the terms of this Agreement.

In fact, the ESG Clean Energy entity itself was originally called Scuderi Clean Energy but changed its name in 2019; its subsidiary ESG-H1, LLC, which presides over a long-delayed power-generation project in the small city of Holyoke, Massachusetts (discussed further below), used to be called Scuderi Holyoke Power LLC but also changed its name in 2019.22

The SEC provided a good summary of the Scuderi Group’s history in a 2013 cease-and-desist order that imposed a $100,000 civil money penalty on Sal Scuderi (emphasis added):

Founded in 2002, Scuderi Group has been in the business of developing a new internal combustion engine design. Scuderi Group’s business plan is to develop, patent, and license its engine technology to automobile companies and other large engine manufacturers. Scuderi Group, which considers itself a development stage company, has not generated any revenue…

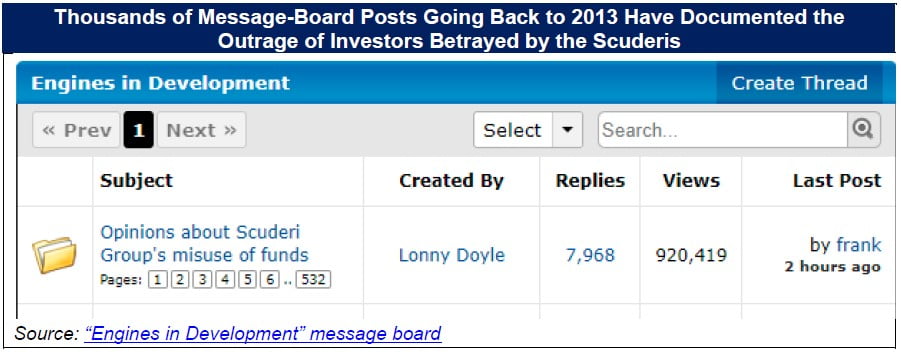

…These proceedings arise out of unregistered, non-exempt stock offerings and misleading disclosures regarding the use of offering proceeds by Scuderi Group and Mr. Scuderi, the company’s president. Between 2004 and 2011, Scuderi Group sold more than $80 million worth of securities through offerings that were not registered with the Commission and did not qualify for any of the exemptions from the Securities Act’s registration requirement. The company’s private placement memoranda informed investors that Scuderi Group intended to use the proceeds from its offerings for “general corporate purposes, including working capital.” In fact, the company was making significant payments to Scuderi family members for non-corporate purposes, including, large, ad hoc bonus payments to Scuderi family employees to cover personal expenses; payments to family members who provided no services to Scuderi; loans to Scuderi family members that were undocumented, with no written interest and repayment terms; large loans to fund $20 million personal insurance policies for six of the Scuderi siblings for which the company has not been, and will not be, repaid; and personal estate planning services for the Scuderi family. Between 2008 and 2011, a period when Scuderi Group sold more than $75 million in securities despite not obtaining any revenue, Mr. Scuderi authorized more than $3.2 million in Scuderi Group spending on such purposes.

…In connection with these offerings [of stock], Scuderi Group disseminated more than 3,000 PPMs [private placement memoranda] to potential investors, directly and through third parties. Scuderi Group found these potential investors by, among other things, conducting hundreds of roadshows across the U.S.; hiring a registered broker-dealer to find investors; and paying numerous intermediaries to encourage people to attend meetings that Scuderi Group arranged for potential investors.

…Scuderi Group’s own documents reflect that, in total, over 90 of the company’s investors were non-accredited investors…

The Scuderi Group and Sal Scuderi neither admitted nor denied the SEC’s findings but agreed to stop violating securities law. Contemporary local news coverage of the regulatory action added color to the SEC’s description of the Scuderis’ fund-raising tactics (emphasis added):

Here on Long Island, folks like HVAC specialist Bill Constantine were early investors, hoping to earn a windfall from Scuderi licensing the idea to every engine manufacturer in the world. Constantine said he was familiar with the Scuderis because he worked at an Islandia company that distributed an oil-less compressor for a refrigerant recovery system designed by the family patriarch.

Constantine told [Long Island Business News] he began investing in the engine in 2007, getting many of his friends and family to put their money in, too. The company held an invitation-only sales pitch at the Marriott in Islandia in February 2011.

Commercial real estate broker George Tsunis said he was asked to recruit investors for the Scuderi Group, but declined after hearing the pitch.

“They were talking about doing business with Volkswagen and Mercedes, but everything was on the come,” Tsunis said. “They were having a party and nobody came.”

Hot on the heels of the SEC action, an individual investor who had purchased $197,000 of Scuderi Group preferred units sued the Scuderi Group as well as Sal, Nick, Deborah, Stephen, and Ruth Scuderi individually, alleging, among other things, securities fraud (e.g. “untrue statements of material fact” in offering memoranda). This case was settled out of court in 2016 after the judge reportedly “said from the bench that he was likely to grant summary judgement for [the] plaintiff. … That ruling would have clear the way for other investors in Scuderi to claim at least part of a monetary settlement.” (Two other investors filed a similar lawsuit in 2017 but had it dismissed in 2018 because they ran afoul of the statute of limitations.23)

The Scuderi Group put on a brave face, saying publicly, “The company is very pleased to put the SEC matter behind it and return focus to its technology.” In fact, in December 2013, just months after the SEC news broke, the company entered into a “Cooperative Consortium Agreement” with Hino Motors, a Japanese manufacturer, creating an “engineering research group” to further develop the Scuderi engine concept. “Hino paid Scuderi an initial fee of $150,000 to join the Consortium Group, which was to be refunded if Scuderi was unable to raise the funding necessary to start the Project by the Commencement Date,” in the words of Hino’s later lawsuit.24 Sure enough, the Scuderi Group ended up canceling the project in early October 2014 “due to funding and participant issues” – but it didn’t pay back the $150,000. Hino’s lawsuit documents Stephen Scuderi’s long series of emailed excuses:

- 10/31/14: “I must apologize, but we are going to be a little late in our refund of the Consortium Fee of $150,000. I am sure you have been able to deduce that we have a fair amount of challenging financial problems that we are working through. I am counting on financing for our current backlog of Power Purchase Agreement (PPA) projects to provide the capital to refund the Consortium Fee. Though we are very optimistic that the financial package for our PPA projects will be completed successfully, the process is taking a little longer than I originally expected to complete (approximately 3 months longer).”

- 11/25/14: “I am confident that we can pay Hino back its refund by the end of January. … The reason I have been slow to respond is because I was waiting for feedback from a few large cornerstone investors that we have been negotiating with. The negotiations have been progressing very well and we are close to a comprehensive financing deal, but (as often happens) the back and forth of the negotiating process takes ”

- 1/12/15: “We have given a proposal to the potential high-end investors that is most interested in investing a large sum of money into Scuderi Group. That investor has done his due-diligence on our company and has communicated to us that he likes our proposal but wants to give us a counter ”

- 1/31/15: “The individual I spoke of last month is one of several high net worth individuals that are currently evaluating investing a significant amount of equity capital into our That particular individual has not yet responded with a counter proposal, because he wishes to complete a study on the power generation market as part of his due diligence effort first. Though we learned of the study only recently, we believe that his enthusiasm for investing in Scuderi Group remains as strong as ever and steady progress is being made with the other high net worth individuals as well. … I ask only that you be patient for a short while longer as we make every effort possible to raise the monies need[ed] to refund Hino its consortium fee.”

Fed up, Hino sued instead of waiting for the next excuse – but ended up discovering that the Scuderi bank account to which it had wired the $150,000 now contained only about $64,000. Hino and the Scuderi Group then entered into a settlement in which that account balance was supposed to be immediately handed over to Hino, with the remainder plus interest to be paid back later – but Scuderi didn’t even comply with its own settlement, forcing Hino to re-initiate its lawsuit and obtain an official court judgment against Scuderi. Pursuant to that judgment, Hino formally requested an array of documents like tax returns and bank statements, but Scuderi simply ignored these requests, using the following brazen logic:25

Though as of this date, the execution has not been satisfied, Scuderi continues to operate in the ordinary course of business and reasonably expects to have money available to satisfy the execution in full in the near future. … Responding to the post- judgment discovery requests, as a practical matter, will not enable Scuderi to pay Hino any faster than can be achieved by Scuderi using all of its resources and efforts to conduct its day-to-day business operations and will only serve to impose additional and unnecessary costs on both parties.

Scuderi has offered and is willing to make payments every 30 days to Hino in amounts not less than $10,000 until the execution is satisfied in full.

Shortly thereafter, in March 2016, Hino dropped its case, perhaps having chosen to take the $10,000 per month rather than continue to tangle in court with the Scuderis (though we don’t know for sure).

With its name tarnished by disgruntled investors and the SEC, and at least one of its bank accounts wiped out by Hino Motors, the Scuderi Group didn’t appear to have a bright future. But then, like a phoenix rising from the ashes, a new business was born: Scuderi Clean Energy, “a wholly owned subsidiary of Scuderi Group, Inc. … formed in October 2015 to market Scuderi Engine Technology to the power generation industry.” (Over time, references to the troubled “Scuderi Engine Technology” have faded away; today ESG Clean Energy is purportedly planning to use standard, off-the-shelf Caterpillar engines. And while an early press release described Scuderi Clean Energy as “a wholly owned subsidiary of Scuderi Group,” the current Scuderi/ESG Clean Energy, LLC, appears to have been created later as its own (nominally) independent entity, led by Nick Scuderi.)

As the emailed excuses in the Hino dispute suggested, this pivot to “clean energy” and electric power generation had been in the works for some time, enabling Scuderi Clean Energy to hit the ground running by signing a deal with Holyoke Gas and Electric, a small utility company owned by the city of Holyoke, Massachusetts (population 38,238) in December 2015. The basic idea was that Scuderi Clean Energy would install a large natural-gas generator and associated equipment on a vacant lot and use it to supply Holyoke Gas and Electric with supplemental electric power, especially during “peak demand periods in the summer.”26 But it appears that, from day one, Holyoke had its doubts. In its 2015 annual report (p. 80), the company wrote (emphasis added):

In December 2015, the Department contracted with Scuderi Clean Energy, LLC under a twenty (20) year [power purchase agreement] for a 4.375 MW [megawatt] natural gas generator. Uncertain if this project will move forward; however Department mitigated market and development risk by ensuring interconnection costs are born by other party and that rates under PPA are discounted to full wholesale energy and resulting load reduction cost savings (where and if applicable).

Holyoke was right to be uncertain. Though its 2017 annual report optimistically said, “Expected Commercial Operation date is April 1, 2018” (p. 90), the 2018 annual report changed to “Expected Commercial Operation is unknown at this time” – language that had to be repeated verbatim in the 2019 and 2020 annual reports. Six years after the contract was signed, the Scuderi Clean Energy, now ESG Clean Energy, project still hasn’t produced one iota of power, let alone one dollar of revenue.

What it has produced, however, is funding from retail investors, though perhaps not as much as the Scuderis could have hoped. Beginning in 2017, Scuderi Clean Energy managed to sell roughly $1.3 million27 in 5-year “TIGRcub” bonds (Top-Line Income Generation Rights Certificates) on the small online Entrex platform by advertising a 12% “minimum yield” and 16.72% “projected IRR” (based on 18.84% “revenue participation”) over a 5-year term. While we don’t know the exact terms of these bonds, we believe that, at least early on, interest payments were covered by some sort of prepaid insurance policy, while later payments depend on (so far nonexistent) revenue from the Holyoke project. But Scuderi Clean Energy had been aiming to raise $6 million to complete the project, not $1 million; indeed, this was only supposed to be the first component of a whole empire of “Scuderi power plants”28 that would require over $100 million to build but were supposedly already under contract.29 So far, however, nothing has come of these other projects, and, seemingly suffering from insufficient funding, the Holyoke effort languished. (Of course, it might have been more investor-friendly if Scuderi Clean Energy had only accepted funding on the condition that there was enough to actually complete construction.)

Under the new ESG Clean Energy name, the Scuderis tried in 2019 to raise capital again, this time in the form of $5 million of preferred units marketed as a “5 year tax free Investment with 18% cash-on-cash return,” but, based on an SEC filing, it appears that the offering didn’t go well, raising just $150,000. With funding still limited and the Holyoke project far from finished, the clock is ticking: the $1.3 million of bonds will begin to mature in early 2022. It was thus fortunate that Viking came along when it did to pay ESG Clean Energy a $1.5 million upfront royalty for its incredible technology.

Interestingly, ESG Clean Energy began in late 2020 to provide extremely detailed updates on its Holyoke construction progress, including items as prosaic as “Throughout the week, ESG had met with and continued to exchange numerous e-mails with our mechanical engineering firm.” With frequent references to the “very fluid environment,” the tone is unmistakably defensive.

Consider the September update (emphasis not added):

Reading between the lines, we believe the intended message is this: “We didn’t just take your money and run – honest! We’re working hard!” Nonetheless, someone appears to be unhappy, as indicated by the FINRA BrokerCheck report for one Eric Willer, a former employee of Fusion Analytics, which was listed as a recipient of sales compensation in connection with the Scuderi Clean Energy bond offerings. Willer may now be in hot water: a disclosure notice dated 3/31/2021 reads: “Wells Notice received as a preliminary determination to recommend disciplinary action of fraud, negligent misrepresentation, and recommendation without due diligence in the sale of bonds issued by Scuderi Holyoke,” with a further investigation still pending. We wait eagerly for additional updates.

Why does the saga of the Scuderis matter? Many Camber investors seem to have convinced themselves that the ESG Clean Energy “carbon capture” IP licensed by Viking has enormous value and can plausibly justify hundreds of millions of dollars of incremental market cap. As we explained above, we find this thoroughly implausible even without getting into Scuderi family history: in the end, the “technology” will at best add a smidgen of value to some generators in Canada. But track records matter too, and the Scuderi track record of failed R&D, delays, excuses, and alleged misuse of funds is worth considering. These people have spent six years trying and failing to sell power to a single municipally owned utility company in a single small city in western Massachusetts. Are they really about to end climate change?

The Case of the Fictitious CFO

Since Camber is effectively a bet on Viking, and Viking, in its current form, has been assembled by James Doris, it’s important to assess Doris’s probity and good judgment. In that connection, it’s noteworthy that, from December 2014 to July 2016, at the very start of Doris’s reign as Viking’s CEO and president, the company’s CFO, Guangfang “Cecile” Yang, was apparently fictitious. (Covering the case in 2019, Dealbreaker used the headline “Possibly Imaginary CFO Grounds For Very Real Fraud Lawsuit.”)

This strange situation was brought to light by an SEC lawsuit against Viking’s founder, Tom Simeo; just last month, a US district court granted summary judgment in favor of the SEC against Simeo, but Simeo’s penalties have yet to be determined.30 The court’s opinion provided a good overview of the facts (references omitted, emphasis added):

In 2013, Simeo hired Yang, who lives in Shanghai, China, to be Viking’s CFO. Yang served in that position until she purportedly resigned in July 2016. When Yang joined the company, Simeo fabricated a standing resignation letter, in which Yang purported to “irrevocably” resign her position with Viking “at any time desired by the Company” and “[u]pon notification that the Company accepted [her] resignation”…Simeo forged Yang’s signature on this document. This letter allowed Simeo to remove Yang from the position of CFO whenever he pleased. Simeo also fabricated a power of attorney purportedly signed by Yang that allowed Simeo to “affix Yang’s signature to any and all documents,” including documents that Viking had to file with the SEC.

Viking represented to the public that Yang was the company’s CFO and a member of its Board of Directors. But “Yang never actually functioned as Viking’s CFO.” She “was not involved in the financial and strategic decisions” of Viking during the Relevant Period. Nor did she play any role in “preparing Viking’s financial statements or public filings.” Indeed, at least as of April 3, 2015, Yang did not do “any work” on Viking’s financial statements and did not speak with anyone who was preparing them. She also did not “review or evaluate Viking’s internal controls over financial reporting.” Further, during most or all of the Relevant Period, Viking did not compensate Yang despite the fact that she was the company’s highest ranking financial employee. Nevertheless, Simeo says that he personally paid her in cash.

Yang’s “sole point of contact” at Viking was Simeo. Indeed Simeo was “the only person at Viking who communicated with Yang.” Thus many people at Viking never interacted with Yang. Despite the fact that Doris has served as Viking’s CEO since December 2014, he “has never met or spoken to Yang either in person or through any other means, and he has never communicated with Yang in writing.” … To think Yang served as CFO during this time, but the CEO and other individuals involved with

Viking’s SEC filings never once spoke with her, strains all logical credulity.

It remains unclear whether Yang is even a real person. When the SEC asked Simeo directly (“Is it the case that you made up the existence of Ms. Yang?”) he responded by “invoking the Fifth Amendment.”31

While the SEC’s efforts thus far have focused on Simeo, the case clearly raises the question of what Doris knew and when he knew it. Indeed, though many of the required Sarbanes-Oxley certifications of Viking’s financial statements during the Yang period were signed by Simeo in his role as chairman, Doris did personally sign off on an amended 2015 10-K that refers to Yang as CFO through July 2016 and includes her complete, apparently fictitious, biography. Viking has also disclosed the following, which we believe pertains to the Yang affair (emphasis added):

In April of 2019, the staff (the “Staff”) of the SEC’s Division of Enforcement notified the Company that the Staff had made a preliminary determination to recommend that the SEC file an enforcement action against the Company, as well as against its CEO and its CFO, for alleged violations of Section 17(a) of the Securities Act of 1933 and Section 10(b) of the Securities Exchange Act of 1934 and Rule 10b-5 thereunder [laws that pertain to securities fraud] during the period from early 2014 through late 2016. The Staff’s notice is not a formal allegation or a finding of wrongdoing by the Company, and the Company has communicated with the Staff regarding its preliminary determination. The Company believes it has adequate defenses and intends to vigorously defend any enforcement action that may be initiated by the SEC.32

Perhaps the SEC has moved on from this matter and will let Doris and Viking off the hook, but the fact pattern is eyebrow-raising nonetheless. A similarly troubling incident came soon after the time of Yang’s “resignation,” when Viking’s auditing firm resigned, withdrew its recent audit report, and wrote a letter “advising the Company that it believed an illegal act may have occurred” – because of concerns that had nothing to do with Yang. First, Viking accounted for the timing of a grant of shares to a consultant in apparent contradiction of the terms of the written agreement with the consultant – a seemingly minor issue. But, under scrutiny from the auditor, Viking “produced a letter… (the version which was provided to us was unsigned), from the consultant stating that the Agreement was invalidated verbally.” Reading between the lines, the “uncomfortable” auditor suspected that this letter was a fake, created just to get him off Viking’s back.

In another incident, the auditor “became aware that seven of the company’s loans…were due to be repaid” in August 2016 but hadn’t been, creating a default that would in turn “trigger[] a cross-default clause contained in 17 additional loans” – but Viking claimed it “had secured an oral extension to the loans from the broker-dealer representing the lenders by September 6, 2016” – after the loans’ maturity dates – “so the Company did not need to disclose ‘the defaults under these loans’ after such time since the loans were not in default.” It’s easy to see why an auditor would object to this attitude toward financial disclosure – no need to mention a default in August as long as you can secure a verbal agreement resolving it by September!

Against this backdrop of disturbing behavior, the fact that Camber just dismissed its auditing firm three weeks ago on September 16th, even with delisting looming if the company can’t become current again with its SEC filings by November, seems even more unsettling. Have Camber and Viking management earned investors’ trust?

Conclusion

It’s not clear why, back in 2017, Lucas Energy changed its name to “Camber” specifically, but we’d like to think the inspiration was England’s Camber Castle. According to Atlas Obscura, the castle was supposed to help defend the English coast, but it took so long to build that its “advanced design was obsolete by the time of its completion,” and changes in the local environment meant that “the sea had receded so far that cannons fired from the fort would no longer be able to reach any invading ships.” Still, the useless castle was “manned and serviced” for nearly a century before being officially decommissioned. Today, Camber “lies derelict and almost unheard of.” But what’s in a name?

Article by Kerrisdale Capital Management