Vltava Fund’s letter to shareholders for the fourth quarter ended December 2020,discussing the three types of inflation being: monetary inflation, asset price inflation, and consumer price inflation.

Q3 2020 hedge fund letters, conferences and more

In the course of our December webinar, we touched upon the subject of inflation. Based upon your questions during the webinar and in the following days, I got the impression that this is an issue frequently causing you concern. Because I lose a bit of a sleep over this from time to time, the theme for this Letter to Shareholders presented itself.

Three types of inflation

When they hear the word inflation, the first thing that comes to most people’s minds is of course rising prices. That is fundamentally correct, but as an economic concept it is not so clear-cut and understandable. Economists define inflation variously. For us as investors, there are three types of inflation that play important roles: monetary inflation, asset price inflation, and consumer price inflation.

Monetary inflation (otherwise known as money inflation) relates to growing money supply within the economy. Therefore, this is not about rising prices per se but about growth in the quantity of money in circulation. Money in this case is understood to consist of cash plus demand deposit bank accounts. The money supply essentially can grow either by banks providing loans in larger volumes, and simultaneously increasing the volume of deposits, or when the state operates with a large budget deficit and the central bank facilitates that by buying up the bonds that the state must sell in order to finance the deficit. The following graph shows how the money supply in the United States as expressed by the M2 monetary aggregate has developed and the annual rate of its growth. The year 2020 was exceptional beyond all previous years and money inflation was very high.

Monetary inflation is a sort of jumping off point for the other two types, asset price inflation and consumer price inflation. Asset price inflation concerns the prices and valuations of financial assets like shares and bonds, but also of the likes of land and real estate, precious metals, collectibles, and that sort of thing.

Whereas money inflation is not visible at first glance to the common person, we encounter asset price inflation everywhere we turn. It is not only in the prices of stocks – which most investors follow – but also in the prices of bonds. In the latter case, this inflation appears as bonds’ low yields, which not only are often close to zero but many times are even negative. Regarding inflation in real estate prices, everyone knows about that who has recently acquired his or her own residence.

Monetary inflation is one of the main reasons for the long-term growth in asset prices. The ever-growing quantity of money in circulation means that ever more and more money is chasing a limited amount of assets and is pushing their prices ever higher. This is nudged on also by the direct and indirect effects of low interest rates, which are themselves partially a manifestation of the high rate of inflation in asset prices.

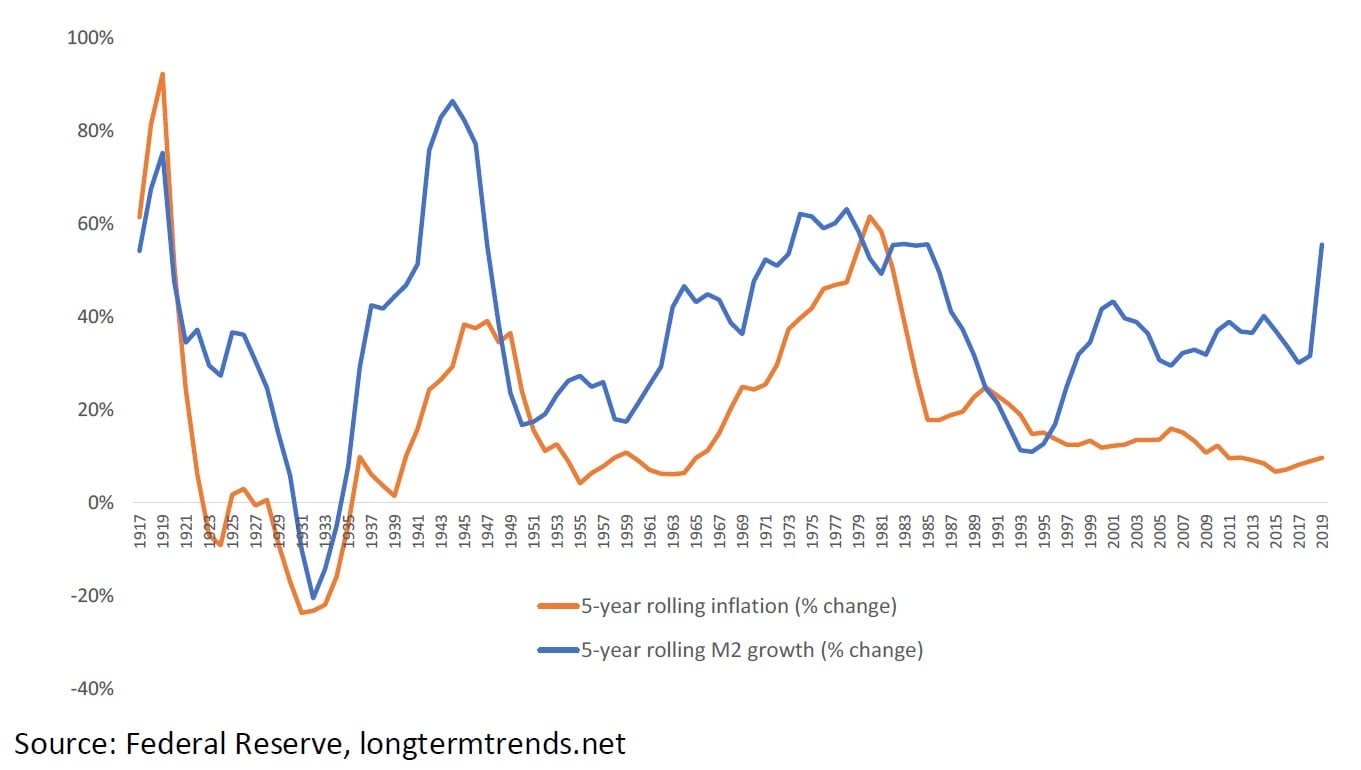

Consumer price inflation concerns the prices of goods and services that we use every day. To a smaller extent, consumer price inflation is also influenced by asset prices, because it is affected by the prices for residences, but otherwise it is primarily driven by nonfinancial items. This inflation is not so simple to measure. There exist various approaches and methods for doing so, and many economists are inclined to the opinion that officially reported consumer price inflation rather underestimates its actual level. I share that view. Moreover, inflation does not affect everyone the same. There also exists a certain relationship between money inflation and consumer price inflation. The following graph shows the 5-year rolling percentage change in the money supply in circulation (M2) and the 5-year accumulated inflation.

At first view, one can see a certain correlation between the two curves. (For simplicity’s sake, I am using statistics from the United States, but the situation is similar almost everywhere.)

Inflation outlook

When I think about inflation as an investor, I am not much interested in what will be its amount in the next few quarters or even in the next several years. Rather, what concerns me is how this game will play out in the end. I strive in my deliberations to model variants of future long-term development and no matter from which side I look at the situation in the end I always come to the same conclusion: high inflation.

I base this view upon the expectation that we can look for many years of above-average money supply growth. Budget deficits are presently enormous in practically all the world’s main economies, and even after the budgetary effects of stimulus intended to mitigate the course of the recession caused by the coronavirus go away there still will remain large structural deficits. It is probable that these deficits will be a good bit larger than they were prior to 2020.

The deficits are in fact so large that it will not be possible to deal with them simply by raising taxes, and the notion that government outlays might be reduced seems to have been forgotten long ago. As I endeavoured to explain in an earlier Letter to Shareholders, the main source of financing will be money newly issued by central banks. The volume of money in the economies probably will grow at an astonishing rate. The question is whether – or rather how quickly and how strongly – will this inflation also be reflected in asset prices (where it already has long been visible) and in consumer prices.

Central banks are today the largest and dominant investors in a broad and growing array of assets. The difference between them and the rest of us is that we must first work, earn money, save some of it, and only then may we invest a part of that money. Central banks can create the money they invest at the click of a mouse button. Then they can use that money to buy assets in the real world – and not just government bonds but also corporate bonds, mortgage bonds, as well as stocks, either directly or through exchanged traded funds, and so forth. With the enormous amounts of newly created money that central banks are pumping into the markets, it is not surprising that the prices of most assets are rising.

So, how will all of this affect the value of money? How can someone be expected to work, to save, to value money and to respect and have faith in its value when that person sees at every turn that it can be produced artificially and in unlimited amounts? In economics, we recognise the phenomenon of scarcity. The extent to which a good is scarce essentially determines its value, and in this case that good is money. Central banks are doing everything to ensure that money will not be scarce. The development of its value will necessarily follow accordingly. Over time, this value essentially always has declined, but it can be expected that the speed of that decline will accelerate. The value of money in terms of everything else will fall all the more quickly as consumers and investors adjust their behaviour in a situation where no one will want to hold onto money.

Precisely here is where the main risk may be hidden. In the past 12 years since the great financial crisis of 2007–2009, global inflation has been surprisingly rather low. It is probable that a slowing velocity of money has played a decisive role in that phenomenon. The equation of exchange (M*V=P*Q) states that there exists a relationship between the money supply in circulation (M), the velocity of money (V), the quantity of assets, goods and services exchanged (Q), and the general price level (P).

To date, the growing money supply (M) has been counterbalanced by a falling V and inflation has remained low. Now we are in a situation where growth in M is gaining pace even more and people are beginning to take notice that something is changing. An ideological revolution in finance may influence also their behaviour and likewise the way they treat money. If rapidly growing M is joined by also growing V, and if over the long term Q is changing only slowly, then we can only expect for P to be rising.

The central banks’ dilemma

The world’s big central banks regard deflation or too-low inflation as one of their main problems and risks. Some of their steps, therefore, are to nudge inflationary pressures up towards their dream level of around 2% annually. Their possibilities to do so are in this sense nearly unlimited. They know that and so rather commonly they declare that they are prepared to do “whatever it takes”. I am not sure that we would hear the same pronouncements from them in a situation when inflation is spiralling out of control, running too high, and it will be necessary to apply the brakes.

There are two main instruments for putting the brakes on inflation: raising interest rates and limiting growth in the money supply within the economy. (For the record, it should be said that it is possible to slow inflation also using fiscal policy, but that assumes the existence of politicians willing to take these unpopular steps and at the same time the existence of voters willing to support them. I am afraid that such a combination cannot be relied upon in today’s world.)

The main burden therefore rests on the shoulders of the central banks. Let us suppose that inflation leaps substantially above 2% and the central banks decide to put on the brakes by slowing money supply growth. In probably many countries such efforts will come up against one practical question: Who will buy the debt that the governments issue every year in order to finance their budget deficits? As I explained a half year ago in a Letter to Investors entitled The dam has broken, the Federal Reserve already had begun again in the autumn of 2019 – which means before the pandemic and at a time of relatively low budget deficits – to buy government bonds because it had seemed that already there was no one in the market capable to absorb such amounts of government debt in the needed volume.

As I write these lines, the European Central Bank is continuously buying more bonds than the euro zone states are issuing. In Japan, the central bank owns such a large share of the government bonds that the market in them is completely dead and illiquid. The Czech National Bank’s balance sheet is today nearly five times larger than before the launch of its monetary intervention 7 years ago. In view of the enormous budget gaps within which the government operates and will continue to operate, the CNB’s balance sheet clearly will continue to grow rapidly. We could continue this discussion with regard to many other countries.

Financing the state budgets of many countries in the world, and especially in its main economies, cannot today be managed without significant support from central banks, and from that viewpoint dependence upon those central banks is gradually growing. It is not very realistic to presume that it will be possible dramatically to limit this support in the interest of struggling against inflation.

Likewise, it will be difficult to fight inflation by means of high interest rates. Inflation can be tamed by gradually raising interest rates, but that is a very painful process. We in the Czech Republic know this also from our modern history after the 1989 Velvet Revolution. But even large, stable and developed economies did not evade inflation. A textbook example can be seen in American inflation at the turn of the 1970s and 1980s. Inflation in the United States had reached 11.35% in 1979 and in 1980 even 13.5%. Paul Volcker, who was Chairman of the Federal Reserve at that time and both literally and figuratively speaking a giant of a man, decided to take strong and decisive action against inflation and in March 1980 raised interest rates from the present 10.25% to 20%. Inflation was brought under control and gradually decreased, but we can imagine the effects this had on economic entities, including households, companies, and governments at all levels.

I am not saying that we should expect inflation of 13% and interest rates of 20%, but, of course, I would not wholly rule that out either. The actual problem, however, will show up even at rates of inflation much lower than 13%. The central banks will to a large extent have their hands tied so far as boosting interest rates is concerned. Even if we disregard the quite substantial fact that significantly jacking up interest rates would create existential problems for no small part of the corporate world and for many households, also coming under great pressure would in particular be national governments and the very central banks themselves.

One of the main reasons that governments are able continuously to operate with large debts and deficits is that they are able to borrow much more cheaply due to the fact that the central banks are taking steps to hold interest rates at well below what would be their equilibrium levels. Low interest costs considerably lighten the burden of large indebtedness and enable the debt recurrently to be rolled forward.

At higher interest rates, this beneficial effect would disappear, costs to service the national debt would grow significantly, and this would have very negative impacts on budget deficits and overall growth of the debt. We are not speaking about small amounts. For example, Japan’s debt is near 250% relative to GDP. If rates there were to be raised by just one percentage point across the entire yield curve, the cost of servicing that debt would gradually become more costly by 2.5% of GDP annually. That is an immense amount, and it reflects merely a one percentage point increase in rates.

Now let us imagine that inflation is running consistently at some still not staggering rate of, say, 5–6% annually and in order to rein it in it would be necessary to raise interest rates to the 6–7% range. Such a rate increase would scarcely be bearable for the budgets of today’s already highly indebted countries.

The interest rate increases would bring problems also for the central banks themselves. Today they are financing themselves very cheaply, often even at negative rates of interest. They are then investing into assets with longer maturities and higher yields. They are like giant hedge funds, and to a great degree they are dependent upon maintaining the present state of affairs. If interest rates were to be raised significantly, their financing costs would soar and very probably the values of the whole range of their assets would plunge. The central banks would have to choose between curbing inflation and maintaining their own solvency. I think the choice would fall to the second of these.

If somewhere I am speaking about the dangers of high inflation, often I hear the objection raised that inflation has been low for a long time and that the present rapid growth in money supply is not pushing inflation upwards. Yes, one could say that, but only if one limits the discussion to the historical period of the past 20 years. If we look somewhat further back into history, however, we will come upon a rather different picture. Many people today do not regard inflation as a threat. What’s more, they presume that governments and central banks will eventually find some easy way to deal with it. I do not believe anything of the kind. The majority of central bankers from the crucial countries have never had to fight inflation, and so they have no experience with it. They are too young for that.

Project Zimbabwe

My grandfather always said that his best ideas come to mind on the toilet and in elevators. He attributed that to the fact that both cases involve a change in pressure. Different strokes for different folks, as the saying goes. In my case, I do my best thinking while engaging in sport. Whenever I am planning to do a long endurance training, which as a rule is a pretty monotonous activity at low intensity, I will let run through my head something that I call an internal monologue. I formulate my opinions on various things and new arguments on the subject pop up in my mind. The majority of my Letters to Shareholders have been written in this manner. I let the internal monologue run its course and then it is just a matter of letting it flow out onto the paper.

Needless to say, perhaps, inflation frequently is the topic of these internal monologues, generally along with that of guarding investors against rapidly depreciating currency. No matter how I look at it, I always come to the conclusion that high inflation is a much greater risk than is too-low inflation. Moreover, it appears to me that the probability that one day we will face an extended period of high inflation is greater than the probability that inflation will long remain very low.

Charlie Munger, the longtime partner of Warren Buffett in Berkshire Hathaway, often urges that in searching for a solution to some problem one should turn the situation around backwards. “Invert,” he says, “always invert.” So, what then must occur in our case such that inflation would never leap upwards? We would need, for example, governments that are capable to bring enormous structural budget deficits under control and voters who would be willing to support that. We would need central banks that would quit manipulating interest rates and would teach governments to rely on themselves to finance their own deficits. We would need to let the processes of creative destruction once again operate and thereby continuously to heal the economy, ridding it of excess and inferior capacities, and so forth. Let us be truly honest: How realistic does it seem to you that these things will ever come to be? Even though they would be beneficial from a long-term viewpoint, they are very painful in the short term and as they recur. In today’s overindulgent world, where everybody clamours for prosperity and we almost never hear the words “hard work” anymore, I would not bet on it. To achieve long-term low inflation also would require, for example, to break the link between monetary inflation and the inflation of the other two types while at the same time convincing people once again to have trust in the value of money. Although a world as described above could theoretically come into being, at present we are far, far from it and are moving farther and farther away from it.

If we look around us and back at history, we can see that practically all the world’s main currencies have almost unbroken histories of losing their value over time. This trend will very probably only accelerate further, and this is the main problem with which investors must contend. When I speak of currencies losing their values, I am not thinking about their exchange rates relative to one another. This is not a debate about whether it is better to own yen or dollars or euro or pounds or francs. It is a discussion about how all the currencies are losing their values against real assets.

With just a little exaggeration, this state of affairs can be given the name Project Zimbabwe. I do not know who originated this expression, but it seems to me very fitting. This is not of course because I would anticipate the same development as in Zimbabwe in terms of inflation and currency depreciation, but because it can stimulate investors to think about the inflation threat. People like narratives, and it is easier to remember a Project Zimbabwe story than, for example, the theory concerning monetary inflation.

Inflation in Zimbabwe under the Mugabe government reached unbelievable levels. In 2008 it rose to an all-time record to date annual rate of 89.7 sextillion per cent. I do not even know how to write such a number. I think it has 21 zeros and means that inflation was so high that it was not possible to keep up in adding zeros to the banknotes. As of the middle of 2020, it still was estimated to be more than 700%.

In such an environment, the owners of cash, deposits and bonds will lose everything. That is simple and straightforward to imagine and remember. In the Czech Republic and in the entire western world we of course do not expect to see a currency lose its value at such a rapid pace. Nevertheless, this is for us as investors the greatest problem we face from a long-term viewpoint.

If some miracle occurs and inflation will be held to just 2% over the long term – which is the inflation target declared by many central banks – then a given currency will lose 40% of its value in the course of a single generation. If long-term inflation will be 3%, the currency will lose 50% of its value within a single generation. If long-term inflation will be 2% but there will be several years along the way when it reaches 5%, then the currency will lose through one generation about half its value, and if inflation during this wave will touch briefly at 10%, then the currency could lose about 60% of its value. I will deliberately not go into the possible worse scenarios. They certainly cannot be ruled out, however, and you can model them yourself. It is quite possible that they seem to you rather improbable and that it would be superfluous even to bother yourself with them. Oftentimes, though, it is the presumption that no risk exists that is itself the source of risk. We must not allow ourselves to forget that high inflation and currency depreciation, and particularly in association with negative real interest rates, help governments to manage their enormous piles of debt and large budget deficits. From their point of view, inflation is beneficial and they are motivated accordingly.

Inflation and the currency depreciation connected with it have been, are, and will be with us always. This is essentially nothing new. Already in the Roman Empire during the first two centuries AD people had to contend with the same difficulty. What makes this problem more complicated for investors, however, is the very great probability that it will be accompanied by interest rates that will in real terms – which means after subtracting inflation – be manifestly and henceforth negative, and there will be a tendency for real rates to fall to levels even more negative than in past years. That makes the whole problem still more urgent, precludes the use of an even larger range of investment instruments, and shrinks the room to manoeuvre. Perhaps the sole possibility for protecting value will be to invest in property assets.

Changes in the portfolio

We sold WH Smith and bought Quálitas Controladora and NVR. WH Smith was our longest-term investment holding. In a couple more months it would have been ten years. We had begun to buy the shares at 500. Since that time, we have received back three-quarters of the original purchase price in dividends. The business ran like a watch and this was progressively reflected in the share price. If the price sometimes seemed to us already excessively optimistic, we took advantage of the situation by reducing our position. We came into 2020 at a share price of 2,600 and while holding about two-thirds fewer shares than at the high point. Then, when the pandemic came along, WH Smith’s business was hurt far more than that of any other company in our portfolio. The share price fell quickly and dramatically, but at that time it did not make sense to sell in an ongoing panic. We therefore decided to wait until autumn, at which time the share price was much more favourable, albeit in our opinion still overly optimistic relative to the company’s future prospects.

WH Smith was established in 1792 and has successfully weathered much worse times. I believe that it will once again return to its previous success. It is a very well run business. Nevertheless, its value at the end of this recession will be lower than before the pandemic. We think that the company can expect another loss-making year and a slower return to its earlier profitability. In the meantime, debt will continue to rise and no small role will be played by a larger number of shares in circulation. We love WH Smith, and it was a very profitable investment. It is possible that we will come back to it one day. But not now, and not at the present price.

You certainly noticed in the October Fact Sheet in the Regional Allocation of the Portfolio graph that a new country had appeared: Mexico. This represents an investment into shares of the company Quálitas Controladora. I will begin with what may seem an unrelated story.

In 1951, a 21-year old Warren Buffett published an article entitled The Security I Like Best. In that article, he highlighted the company Geico as his most favourite company. At that time, half of the Geico shares were owned by Graham-Newman Corp., which was headed by none other than Buffet’s great mentor and the teacher of all intelligent investors, Benjamin Graham. That initial 1948 investment in the amount of $712 000 grew for Graham to $400 million in 1972.

Then Geico slipped into temporary difficulties and the share price fell from $61 to $2 in 1976. At that time Buffett came into the game and for Berkshire Hathaway he gradually bought one-third of Geico at a cost of $46 million. With Buffett’s support, Geico began to be successful again and thanks to share buybacks Berkshire’s stake in Geico gradually grew to a half. Berkshire bought the other half of Geico in 1995 for $2.3 billion. Since that time, Geico has been fully owned by Berkshire and its value today is estimated at $40–50 billion. During Buffett´s long career Geico was one of the largest investments compared to the assets he had at the time of the purchase, and in terms of return, it was perhaps the best investment.

Why am I writing about this? Geico is the second largest auto insurer in the United States. Quálitas Controladora is its equivalent in Mexico. It has a larger market share (30% versus 14% in Geico’s case), however, as well as better fundamental indicators (ROE, combined ratio), and it is in a faster growing market (only 39% of automobiles in Mexico are currently insured). Our decision to buy Quálitas shares was not made because Buffett owns a similar business in the United States. Rather, it is because we, like Buffett, came to the view that a similar business could be an excellent value creator and addition to the equity portfolio.

Quálitas Controladora was established in 1993 and we came across it in 2016 during an investment conference in Madrid. Since that time, we have been following the company and it was just a question of time before it would appear in Vltava Fund’s portfolio. When I last spoke with Mexican analysts and brokers, during October, they complained to me about the near absence of interest among foreign investors for Mexican shares and that as a result their market had not recovered much since last spring. In our eyes, lack of interest among investors looks like an excellent buy signal, and we liked the price at just 85 pesos as well.

At the beginning of December, we bought shares in the American company NVR. It is another of those companies that for years we have been itching to buy. Its business is in residential construction. At first glance that may not sound all that attractive, but NVR has a rather unique business model that enables it to do business with relatively small capital requirements, as a result of which it achieves levels of returns on equity and on invested capital that most (profitable) technology firms can only dream of. In the case of NVR, moreover, we think that we can take advantage of a trend taking shape and that can play out for many years to come of people moving out of the centres of large cities to the suburbs and countryside.

Although the American market constitutes about half of the world equity market, a large majority of companies are outside of the United States. We believe it makes a lot of sense to search among these for good investments, and that is true for both developed and emerging markets. At present, we have three investments in emerging markets: Samsung (I find it strange to regard South Korea as an emerging market when it is one of the most technologically advanced countries in the world), Sberbank and Quálitas. Each of these has a unique position in its market and in its sector, and we think that they are and will continue to be very beneficial for us. We expect that in the just beginning decade emerging markets will perform better than the US market. As was the case in the first decade of this century. We try to take an advantage of this very selectively, but most of the portfolio will remain in developed markets.

Last year was an uncustomarily active one with regard to the number of transactions in the portfolio. There are three main reasons for that: big share price swings during the year, a large inflow of new money to the Fund in the second quarter, and our intention to increase somewhat the number of titles within the Vltava Fund portfolio.

I do not want to repeat unnecessarily what we spoke about a month ago in the webinar, but I nevertheless must remark that, inasmuch as we found ourselves last year in a global pandemic and deep economic recession that no one could have expected a year earlier, what surprised me most is how little this situation has negatively manifested itself in the profitability of those firms whose shares we hold. If we somewhat simplify by considering the earnings per share for nonfinancial companies and book value per share for financial companies to be an indicator of value, then we can say about three-quarters of our companies were from that point of view at their all-time highs as of the end of 2020. That is something we absolutely never would have expected back at the end of March. Furthermore, the data shows that growth in their profitability is picking up speed and 2021 should from that perspective carry nearly all of them to new all-time highs. Moreover, we anticipate notable growth in share buybacks. These were temporarily subdued last year, and, as a result, quite a few companies have surplus capital. This year, the surplus should flow more quickly in the direction of the shareholders.

In the last Letter to Shareholders, entitled Technoparty, I described how the character of the market had distinctly changed as of the beginning of September. For a few previous years, investors were selling shares of low-priced and in many cases very attractive businesses and used the money thus obtained to buy shares of expensive and oftentimes even money-losing businesses with minimal prospects for future prosperity. As a result, the shares of loss-making companies in the first eight months of last year substantially outperformed the shares of profitable companies. This is no longer the case. That perverse trend reversed itself right at the beginning of September, continued uninterrupted, and in November quite significantly strengthened. I wish I could say that investors came to realise that it is not every company’s raison d'être to drive its share price to the highest possible level but rather to produce profit and an attractive return on capital. The most probable reason for the sudden show of wisdom by market participants, however, is that every bubble breaks in the end of its own excess and the valuations of some shares were already truly enormous.

Although four months is not sufficient time for drawing conclusions, it is altogether possible that this trend will continue even for several years. It certainly would be good to look back and recollect how a similar change in trend occurring at the beginning of the year 2000 wreaked havoc upon the prices of popular and extremely overpriced shares and how well it worked out for those high-quality and very profitable companies that previously had been overlooked. The relative difference in their subsequent returns was measured not in tens of percentage points but in hundreds of percentage points. In today’s market, the cards have been dealt similarly.

Daniel Gladis,

January 2021

For more information

Visit https://www.vltavafund.com

Write us [email protected]