Dear Investors,

First a housekeeping note. If you are a client and have not received your printed quarter end newsletter and statement in the mail please let me know. There still appears to be significant postal service delays so I can send you an electronic copy in the meantime.

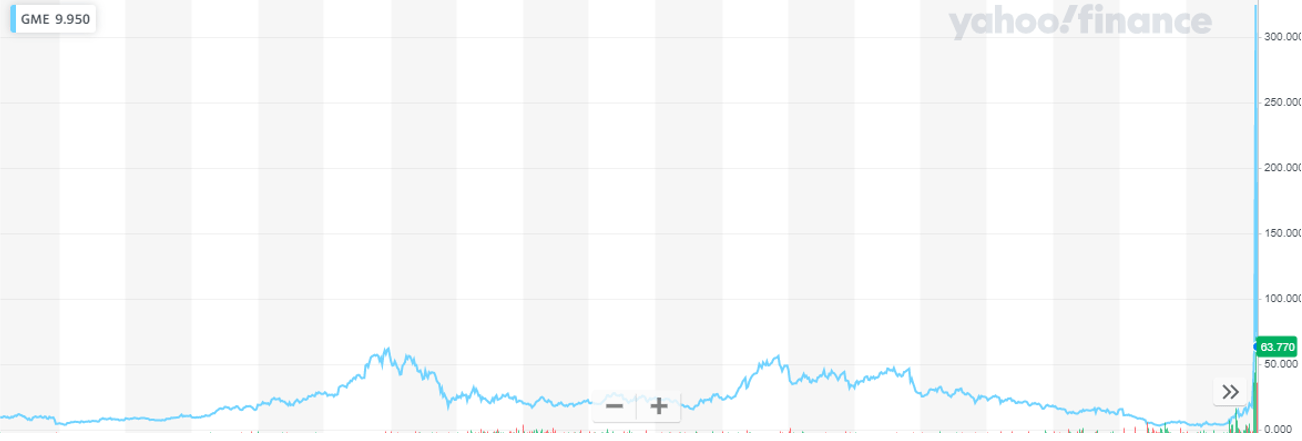

If you follow the markets you’ve all by now probably heard about the strange story of GameStop. The brick and mortar retailer whose stock spiked from the teens to almost $400 (I think it may have reached that point or higher in the middle of one of the days). You can see how crazy it is in the stock price chart below.

GameStop (GME)

GameStop is traditionally compared to Blockbuster or some other dead or dying retailer. Short-sellers have described it as “a melting ice cube.” That might be an apt description, if modified to “The World’s Slowest Melting Ice Cube.” GameStop isn’t a terrible company, but it isn’t great either.

Years ago, I talked about how GameStop was different than Blockbuster. Now, I’ll expand on that difference to include other retailers that were dying before, and more retailers since, COVID. Unlike Blockbuster, department stores and apparel retailers, GameStop has tiny stores with few staff. Therefore, their fixed expenses are much lower. Additionally, GameStop’s tiny stores are packed with mostly small, expensive merchandise ($60 AAA video games). On the other hand, Blockbuster had enormous stores filled with cheap (a couple bucks) rentals. Apparel retailers also face another risk, fashion trends. If they buy the wrong designs or too much of one trend and the clothing doesn’t sell, then they are left with two equally bad choices. They must heavily discount the merchandise (perhaps damaging brand cachet) before the season ends, or be left with piles of unsold inventory to store and try to resell next year when it’s probably going to be even more out of style.

Video game sales are obviously also seasonal. (What kid or adult isn’t asking for a new game or console system for Christmas or Hannukah?) If, however, the new Call of Duty game isn’t selling as fast as predicted, the game won’t be “out of season” and unsellable like a wool sweater in the middle of summer. So, inventory issues aren’t as severe with GameStop as they might be with other retailers.

As of their latest financial report, GameStop has $446M in cash and an additional $141M in restricted cash to go against $213M in lease liabilities due in a year and $246M in short-term debt. Prior to the pandemic, the company was generating cash from operations albeit declining from over $500M a few years ago to just over $300M in FY2019. During COVID, cash flow went negative but the company has enough liquidity to stay afloat.

So, what’s all the recent hoopla? The first ingredient is hedge funds and others shorting a company that isn’t doing well, but isn’t in danger of imminent death. “Shorting” or short selling is something investors can do when the believe a company’s stock will decline and they want to make money on that decline.

Short sellers had already made money as the stock fell from a high of $40-$50 in 2013-2014 to below $5 a share during the depths of the COVID panic. Were some short sellers pushing their luck? Probably. There probably isn’t much money to be gained by shorting the stock as low as the price got, but GameStop isn’t a terrible company.

The stock price started rising with the prospect of a new console sales cycle and a trio of e-commerce vets from Chewy.com joining the board and then later the announcement of a lead engineering hire from AWS.

Second, a Reddit message board suddenly became interested in the stock. Why is a mystery to me. Reddit seemed to have done a good job identifying a company whose stock price was potentially depressed compared to its fundamentals and its future prospects. They also correctly identified that since a significant amount of the stock was shorted, there was a potential for gain.

When someone bets against a company, or “shorts the stock,” it works like this. Let’s say the stock of ABC Company is at $20 a share. The short seller borrows a share of stock for an existing stockholder and agrees to return it at a later date, betting they will be able to buy it back later (say, three months) for less. The short seller sells that borrowed share of ABC Co in the market at $20. Three months go by, and the stock price has declined to $10. They were correct. They buy a share at $10 and return that share to the original shareholder from whom they borrowed it, as promised. Sold at $20, bought back at $10, and so they earned a tidy $10 profit or a 50% return.

The flip side of short selling is this. If you are wrong, then you have to buy back the share at a higher price and you lose money. You have only to look at a long-term chart of Amazon, Apple, Google, Visa, or whatever successful company you like to see how wrong things can go. Your losses as a short seller are potentially unlimited! Your gains, however, are always capped at 100%. The lowest that share of ABC Co could go is from $20 to $0.

Additionally, another thing is working against short sellers. Say you manage a portfolio of $100 and you shorted ABC Co at $20. Your short position in ABC Co is 20% of your portfolio ($20 divided by $100). What if ABC Co doesn’t go down and instead doubles? It’s worth $40? Now, your short of ABC Co is 40% of your portfolio. What if it keeps going up? What if it reaches $120? Your portfolio is only $100, so you can’t even afford to buy back the share! Of course, brokerages don’t want this to happen. That’s why, usually, well before things get out of hand, they tell you either to put more cash into your account or they say they are buying back that share of ABC Co now for you, while they know you can afford it. The brokerages don’t care if you are Joe Schmoe or Johnny Big Shot Hedge Fund Billionaire. This dynamic is why prudent short sellers who want to manage risk typically limit the size of one individual short in their portfolio to perhaps 1% or less.

Now, back to our GameStop hoopla. For reasons I don’t understand, one hedge fund, Melvin Capital, had a short position in GameStop that was 15% of their portfolio. Having short positions this large is very risky if the stock price moves against you.

So, if lots of people are short a stock and in size and the price starts moving higher they may be forced to cover their short positions and buy back shares. This forced buying can also put more upward pressure on the stock price.

Another interesting phenomena that may have contributed to the big run-up in GameStop shares is the use of options, specifically deep out-of-the-money options. I’ll preface this by saying I do not use options nor am I an options expert. I’ll keep the explanation basic and refer you to other sources if you want more detail.

Below is an example of how options work at the most basic conceptual level. The math behind a lot of it and how dealers and investors hedge and trade is extremely complex. The goal below is just to illustrate a simple point to explain the nuts and bolts of how it works.

Again, we’ll use ABC Co stock trading at $20 a share and we will use one share as an example even though options are usually in lots of 100 shares. Let’s say I purchase a call option with a strike price of $50 dated six months from now. That means that from now until six months from now, if ABC Co stock ever reaches $50 (or more) a share, then I have the right but not obligation to purchase a share of ABC Co at $50 from the dealer who sold that option to me. If it never gets to $50, then the option expires, is worthless, and I get nothing. Because it’s not a sure thing, deep out-of-the-money (meaning the current stock price is far away from the strike price) options are cheap. Maybe I paid $2 for that ABC Co call. So let’s say the stock price goes from $20 to $60 in five months. Because $60 is higher than $50 and it reached $50 or more before six months, I have the right to buy a share of ABC Co at $50. So far, I paid $2 for my option and $50 for the ABC Co stock. If I turn around and sell the share of stock at the current price of $60 my profit will be $8 ($60 in proceeds from the sale minus $2 option cost minus $50 cost to buy the share). My profit is $8 on an initial investment of $2 or a gain of 300%. Options allow investors to magnify their bets (and risk) and make large bets with only a little amount of money.

If I’m a dealer selling options, then I want to make money selling you financial products. I don’t want to worry about exposure to all these different stocks. Let’s say I sold call options on ABC Co at $50 to 100 different people, and the stock is $20. I want to manage my risk. Even though $20 is a long way from $50, it could get there. Just in case I have to deliver these ABC Co shares to you when you exercise your option maybe I’ll buy a few as a hedge. Then, let’s say in a few weeks or months, the stock price goes up to $35. I would think, it’s now even more likely to reach the $50 strike price. Since I might really have to deliver these shares, I better buy some more. Then maybe the stock goes to $45. Now, I might certainly have to deliver, so I better make sure I have shares for all my 100 people. I buy more shares.

What can happen is what happened with GameStop. When dealers sell deep out-of-the-money options on a skyrocketing stock, the dealers are forced to buy more of the underlying stock as a hedge. The actual math that goes into this and how the hedges are done is infinitely more complex than this simplistic example, but the basic idea is the same. In certain circumstances, dealers hedging options can put upward pressure on a stock price.

Now, we come to the last part of the GameStop saga. Many brokerages sell their order flow. This is legal because “supposedly” selling the order flow to a third party for execution is supposed result in improved pricing for customers versus simply sending the order directly to an exchange to be executed. Again, this is not a subject I’m well versed in because it has minimal impact on me and my clients’ investments. The longer you hold an investment (and we’ve held some more than a decade) the less meaningful a fraction of a cent differential on the purchase becomes. My clients are much better served when I focus on identifying successful companies and avoiding bad ones, helping them plan for retirement, and managing their personal finances than if I were trying to figure out where that 1/10th of a cent from those Microsoft shares we purchased nine years ago went. These large firms can see, in aggregate, what is happening in brokerages fractions of a second before orders are filled. That means, they know if lots of people are buying a certain stock, say, GameStop. To be honest, since the forum on Reddit is public, they also knew about it just from people talking about it. Many sophisticated funds have automated social media and web crawling software. It probably also wasn’t a secret that Melvin Capital was dangerously short GameStop.

What we had with GameStop was a story that was far more nuanced than just a simple David vs. Goliath. You needed many complex things happening at the right time. You needed a small(er) stock where a large group of individuals could potentially move the stock price. You needed that stock to be legitimately undervalued or at least not as bad as conventional wisdom so your initial idea of buying the stock doesn’t seem crazy. You also needed a lot of people or funds to be short the stock, some with very dangerous risk management practices. You need a catalyst to start shares moving upwards like new board members and executives with successful e-commerce backgrounds. You then needed a reason for people to keep piling in whether that was individual investors on Reddit seeing it as a Main St. vs Wall St. battle or firms front running investors’ orders. After all, what self-respecting fund or trader wouldn’t also want to get their share of the Melvin Capital carcass too?

I know the media loves stories framing stories in the most simplistic terms possible such but the reality is that situations are usually much more complex. In this case you needed a lot of things to happen at once to get a situation like GameStop.

Disclaimer

Historical results are not indicative of future performance. Positive returns are not guaranteed. Individual results will vary depending on market conditions and investing may cause capital loss.

The performance data presented prior to 2011:

- Represents a composite of all discretionary equity investments in accounts that have been open for at least one year. Any accounts open for less than one year are excluded from the composite performance shown. From time to time clients have made special requests that SIM hold securities in their account that are not included in SIMs recommended equity portfolio, those investments are excluded from the composite results shown.

- Performance is calculated using a holding period return formula.

- Reflect the deduction of a management fee of 1% of assets per year.

- Reflect the reinvestment of capital gains and dividends.

Performance data presented for 2011 and after:

- Represents the performance of the model portfolio that client accounts are linked too.

- Reflect the deduction of management fees of 1% of assets per year.

- Reflect the reinvestment of capital gains and dividends.

The S&P 500, used for comparison purposes may have a significantly different volatility than the portfolios used for the presentation of SIM’s composite returns.

The publication of this performance data is in no way a solicitation or offer to sell securities or investment advisory services.