Spending $26.95 to pick Ray Dalio’s brain for over 16 hours listening to the audiobook appears fantastic value to me. The thought crossed my mind to offer Mr. Dalio a charity donation in his name if he gave me the opportunity to make it a two-way conversation over lunch. But that wouldn’t have been consistent with his (or my) Principles. Instead, I’m offering my radically truthful review for $0. The challenge for Mr. Dalio is whether reading this review will be time well spent. Ray, you do not know my ‘believability’ – and that is a key deficiency in your principles you might want to address, especially when applied to the next phase in your life. Let me expand.

Principles details an organically grown set of rules to run a business. Ray shows how his principles have enabled him to build the world’s largest hedge fund and stipulates that anyone can build a great organization following his rules. His success speaks for itself - he is the first to point out that anyone should adopt their own principles. The common theme is a deeply rooted belief that running a business is similar to managing a professional sports team- taking this to an extreme, which Ray does, creates stimulating food for thought.

Ray’s definition of “principles” is not what many might expect. Principles go beyond a Rotarian Four-Way Test; they go beyond the Ten Commandments. Principles is more like a Harvard MBA class in waiting (he loves case studies, refers to them as case law), they are an assortment created by someone who, in his own assessment, is an engineer at heart. Engineers get things done, even if messy at first, trial and error is a virtue. I’m married to an engineer and have learned to appreciate this approach. In contrast, I’m a computer scientist. Computer scientists like to generalize problems even if the sample size is one; they like models and abstraction. The approaches are similar, yet distinct: engineers may get to market faster, but there’s a risk that things get too convoluted, too complicated once the complexity increases (you propose an app to wade through the ‘pile of principles’). The computer scientist might never make it beyond the modeling stage, too worried about that potential bug. My hunch is that without their benevolent despot, at some point, newly introduced principles (or old ones re-interpreted) will clog the machine. At that point it might be time to call on a computer scientist to help unclutter things. That said, who am I to criticize Ray’s principles? In fact, this isn’t meant as criticism, just a forecast. Any approach to managing a business will have potential pitfalls, being aware of those pitfalls will help stakeholders navigate them.

To appreciate Principles, a passion for investing is helpful, if only because of the industry lingo used. At first, I thought it’s a pity that this might limit his audience. But, no, it makes Principles authentic. Instead, I look forward to also reading books of other thought leaders passionate about their field with a completely different mindset.

Since investments are the topic of discussion at various times, let me shout out a big thank you to Ray, as he sheds light on what I believe is one of the biggest misconceptions in the community, notably also amongst hedge fund managers. Many have heard hedge fund managers tend to look for trades that have little downside, but much upside. A lot of investors, notably hedge fund managers, take that too literally, as they pursue options strategies. Buying an option costs fairly little (the premium), but offers potential upside that may be much greater. The problem with options is that they have what’s called time decay, notably that your option may expire worthless. In an era of low volatility, lots of options expire worthless. Options may also be used as insurance; but that, too, can be costly. Don’t get me wrong: there are worthwhile options strategies, but they are not the holy grail of low risk / high reward. Principles does not go into detail of how options work, but has an explainer of diversification. It is generally understood that diversification is the one free lunch available on Wall Street. Ray points out the obvious, notably that stocks are highly correlated with one another, so investors should consider uncorrelated return streams. At Bridgewater, he says, they combine as many as 15 different return streams from different asset classes; I challenge any reader to name just a few, let alone use multiple in their actual investments. Importantly, he argues, the way one achieves high potential upside with limited downside is by combining uncorrelated return streams. That’s very different from buying options (an options strategy may or may not be part of these return streams, but that’s a subordinate issue) in hopes of striking gold. Yes, Ray discusses gold, too; get a copy of the book to learn more.

Before I go much further in reviewing Principles, it may be helpful to review Ray’s agenda in publishing the book, as it helps to understand what this book is and what it is not. When I heard Ray as a guest on public radio last week, the cynic in me flagged this must be a symptom of a market top. But I recalled he had also given a “TED Talk”, so I was curious enough to question my gut reaction, leading to my downloading and listening to the audiobook of Principles. Ray is straightforward about his agenda: he considers his principles part of his legacy, wants to pass on the institutional knowledge he has helped build. In publishing the book, he also wants to have bright talent consider working for Bridgewater, as his firm had received bad media coverage about cult-like culture that apparently hampered its recruiting efforts. Ray makes it clear that his firm is the exact opposite of a cult. I agree, but read and judge for yourself.

While his book should be cherished by any aspiring entrepreneur, it is not squarely aimed at those running a small business. Sure, the book makes it clear that anyone following his principles can build a great organization, but at various sections in the book it becomes clear he is focused on running a large organization. I have no problem with that, but it helps to understand the context as to why he wrote the book.

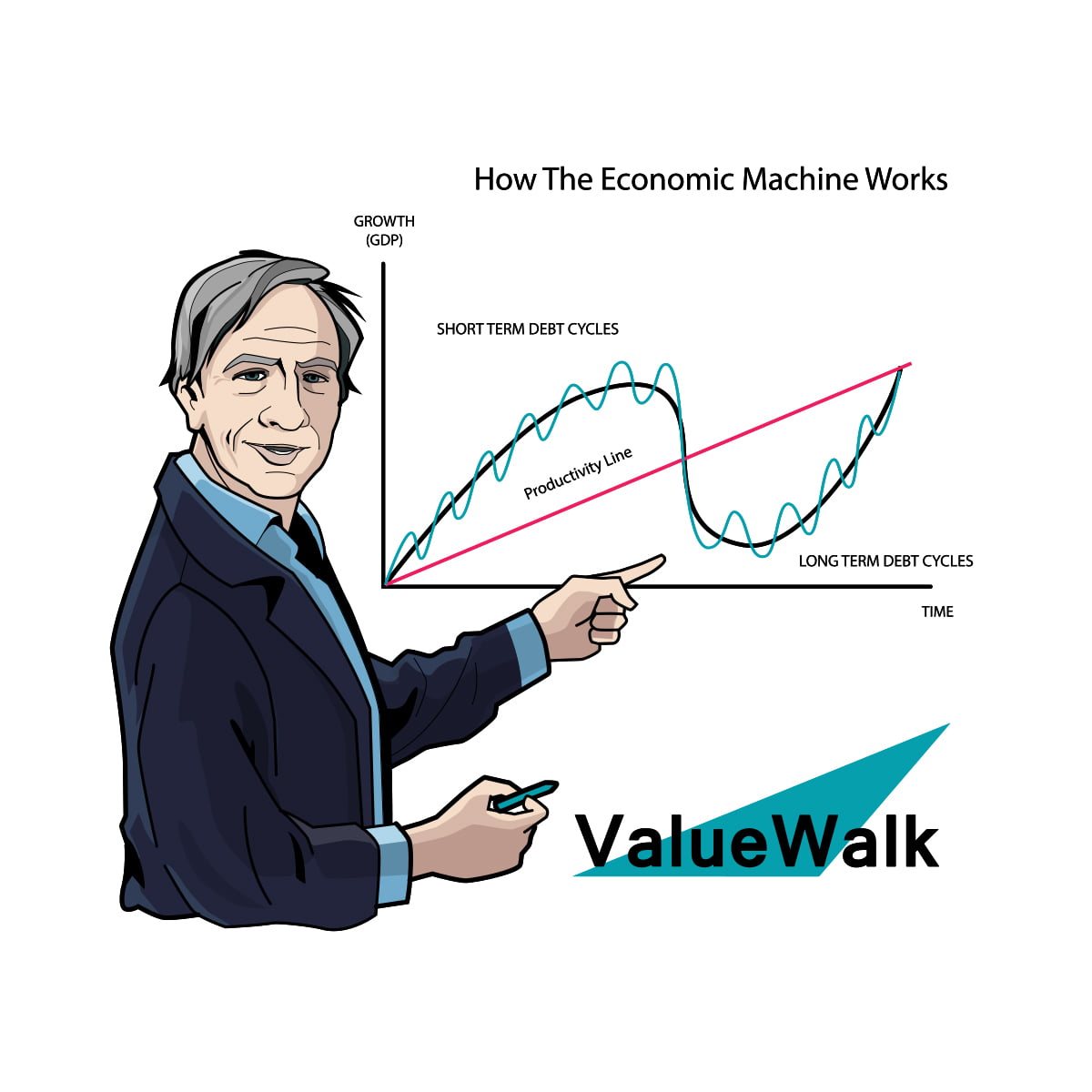

Ray says successful entrepreneurs tend to be “shapers”, that is persons who can see the big picture, yet pay attention to detail (think Steve Jobs). His style should resonate well as what he profiles as the archetypical small business person: anyone running a small business has big dreams, yet takes care of the details. In fact, I can’t help but contemplate that maybe Ray is a small business person himself, of sorts. One who has managed to grow a big organization by using his principles for many management details – the “machine” as he calls it.

The context is relevant though, as everyone, including Ray, is hostage of his environment. Ray makes a convincing case that meritocracy is key to success; that is, decisions are made based on believability-weighted decisions. He then goes to great lengths to explain the “machine” he has built to develop profiles of his staff. He has run his firm like a petri dish in a closed environment. He argues that, with limited time, it isn’t worthwhile, even potentially hazardous, to listen to unqualified opinions. That approach has worked for him as he has the resources to run his social experiment in-house. But is this the most efficient way? Is it most efficient to grow your talent, weed out a third that’s not up to the task, impose radical transparency and radical truthfulness on them, even if that’s not their nature? It may well be, but there’s a risk standards slip once the benevolent despot is out of the picture, no matter how big the pile of principles is.

While I have never called it such, I have applied radical transparency to running my investment business. Unlike most in the industry, for the past fifteen years, I have shared my views and positions with the general public. What do I get in return? Feedback. We have learned to filter that feedback into our idea generation engine, and to stress test our hypotheses. I have most appreciated that as I could not have possibly obtained that feedback with the limited resources I have in managing my comparatively small team. Ray may have brilliant experts in-house, but he is missing out on the brilliance out there. He scoffs at the public’s input in his book; after all, the mob does not have your optimal investment performance in mind. I beg to differ: just as one can develop models to rate the believability of your team, you can develop models to rate the believability of the public or any subset of the public, including those of specific strangers. Take Twitter as the simplest example: everyone can broadcast anything on Twitter, but you can curate who you want to listen to. Folks offer their analysis for free, you might as well harvest the value, separating quality from noise.

Like many asset managers, we get visits by strategists of major financial institutions. They provide thoughtful insight. But the so-called strategist at major institutions are not allowed to put their money where their mouth is. While I appreciate their input, it is very different from that of an employee who has his or her own sets of conflicts; and that is yet again very different from the feedback provided by a complete stranger. And while many investment professionals ridicule retail investors, I have learned to appreciate them. We have some public products, so I can see the flows; there are some pretty smart cookies amongst retail investors.

What I’m getting at is that Bridgewater – to just name Ray’s firm as an example – may at some point need to turn outward. And with that, I don’t mean it has to be unleashing Big Data indiscriminately (Ray provides criticism I agree with). But I believe the successful machine of the future may well include an assessment of the public. Are the principles flexible enough, can they evolve?

I’m not telling you anything you don’t know already, as it is increasingly pervasive in a variety of industries, most notably online advertising. In my humble opinion, it will be crucial for Ray’s next ambition: to help policy makers navigate tough decisions. You are not going to get members of Congress to adhere to the rigors of your meritocracy, yet it would be a pity to just disregard what you have created. So build a system that’s open. Build the machine that helps policy makers make the right decision based on merits. Incidentally, a machine that helps policy makers by sourcing input from the public, amongst others, could also be of use to Bridgewater.

One more note on your big-business-mindset, Ray: you argue that a janitor should be an in-house employee, as it is more cost effective as long as the person is full-time. Can it be that you are biased? Can it be that you love building machines so much, so that you in-source the janitor simply to prove your point? Good for you. And, clearly, it was not your goal to write the how-to-book for the smalltime entrepreneur. For anyone but big business, I allege that outsourcing non-core functions can be most effective. Indeed, in today’s world, it is so much easier to start a business because you can outsource so much. The culture in a janitorial firm is different from that in an investment firm; I would also think the typical employee on the investment side at Bridgewater is going to be more open to meritocracy than your janitorial division.

If you have read my ‘review’ all the way to this point, let me provide a business idea for the new phase in your life, if you haven’t done it already: hold periodic auctions for a charitable cause – open to the public - for discussions over lunch. Especially in the aftermath of the publicity you generate in promoting your book, you should be able to raise a fair amount to satiate hungry minds that want to discuss Principles with you.

Finally, one criticism: get off your butt, start doing exercise and don’t merely talk about the 2nd order benefits. Your family will have you around longer if you invest in your physical wellbeing.

Ray: if you’d like me to expand on the above or help in building that open machine, give me a call. For everyone else, if you believe this analysis might be of value to your friends, please share it with them; follow me on LinkedIn or Twitter.

Axel Merk

President & CIO, Merk Investments