Saber Capital Management’s commentary for the month of August 2019, titled, “Interest Rate Fears And The Dreaded Yield Curve and net interest income”

Dear Investment Partner,

Despite the general markets still near all time highs, I think there are some interesting values right now. I’m looking at a number of ideas, researching new companies as well as refining my valuation work on a few that have been on the Saber Capital watchlist for years.

Q2 hedge fund letters, conference, scoops etc

This isn't always the case, but there are current opportunities to allocate capital if you have excess capital "on the sidelines", earning what is getting closer and closer to 0%. As I wrote back in December, I have no idea where the market goes in the next year, but I am excited about values in certain stocks. It appears some parts of the market are incredibly overpriced (certain software stocks, VC funded tech startups, "low beta" consumer stocks), while other parts of the market seem to be offering great value with significant margins of safety.

One simple example is our boring old Wells Fargo, which is now priced at nearly a 12% earnings yield, which includes a whopping 4.6% dividend (which is a dividend that is only around 40% of the total earnings and also one that has been growing each year and likely will continue to grow over time).

I received an email from a company that I've followed for years in the homebuilding industry. It's a small-cap homebuilder that just issued an unsecured 7 year note at 4% interest. I'm not sure why you'd want to lend at 4% to a cyclical business without collateral when you can get 4.6% by owning a stake in one of the most stable businesses in the S&P 500 and still have 60% of the earnings left over (which Wells is using to buy back its own stock... a nice investment with WFC trading at under 9 P/E).

I did some research on why the banks might be trading at such a large discount to assets like the loan I described above. I went back and looked at the last few decades to understand how profits have reacted to rising/falling interest rate environments. Here are some notes that I've compiled if you care to take a look (what could be a more fun or productive use of your time than reading about historical data on the US banking system?)

The Dreaded Inverted Yield Curve

It’s common sense that if you are lending money to someone for a decade, you are naturally going to want a higher interest rate than a short-term loan that will be repaid in a few months. However, on certain occasions a strange phenomenon occurs: lenders to the US government demand less return for a long-term loan than they do for a short-term one. This is the much feared “inverted yield curve”, which, as famed investor Stanley Druckenmiller likes to say, has predicted 9 of the last 4 recessions.

This week, the 10-year US Treasury yield dropped below the 2-year. Incredibly, the 30-year Treasury traded at a 2% yield yesterday. Put another way, this 30-year bond trades at 50 times earnings, and these earnings are obviously guaranteed, but they’re also guaranteed not to grow. Treasuries trade at similar valuation levels to high flying software stocks these days.

There are lots of reasons why the pundits believe that a yield curve inverts, but one reason is when investors become fearful, they plow their money into longer term bonds as a “safe haven”. The implicit logic is that investors would rather lock in a sure 2% return than risk getting even less if the economy turns south and rates fall further. One asset that allows you to “lock in” a much higher interest rate than Treasury bonds is WFC at $44 per share. As mentioned, the dividend yield is 4.6% and unlike the bonds, this stream of cash can and likely will grow over time. More importantly, if we add the buyback "yield" (described here), we're getting a total yield of an incredible 16% at the current price.

Why Are Banks Cheap?

One reason is the fear that interest rates go lower and compress profit margins.

Banks make money in two main ways: the first is gathering funds by paying interest to depositors and then lending or investing that money at higher interest rates, pocketing the spread (“borrow at 3, lend at 6, play golf at 3″… the classic business of a bank is a pretty straightforward business). The second main category of revenue is called “non-interest income”, which is basically everything else including asset management, trading revenue, investment banking, and other fee-based income that banks collect from their customers.

In the first business segment, the problem with rates going lower is that banks can’t reprice their deposits as fast as their assets. This “asset sensitivity” means that banks earn more net interest income as rates rise, and less as rates fall. If rates stabilize, margins eventually stabilize, but if rates are fluctuating, margins will fluctuate as well.

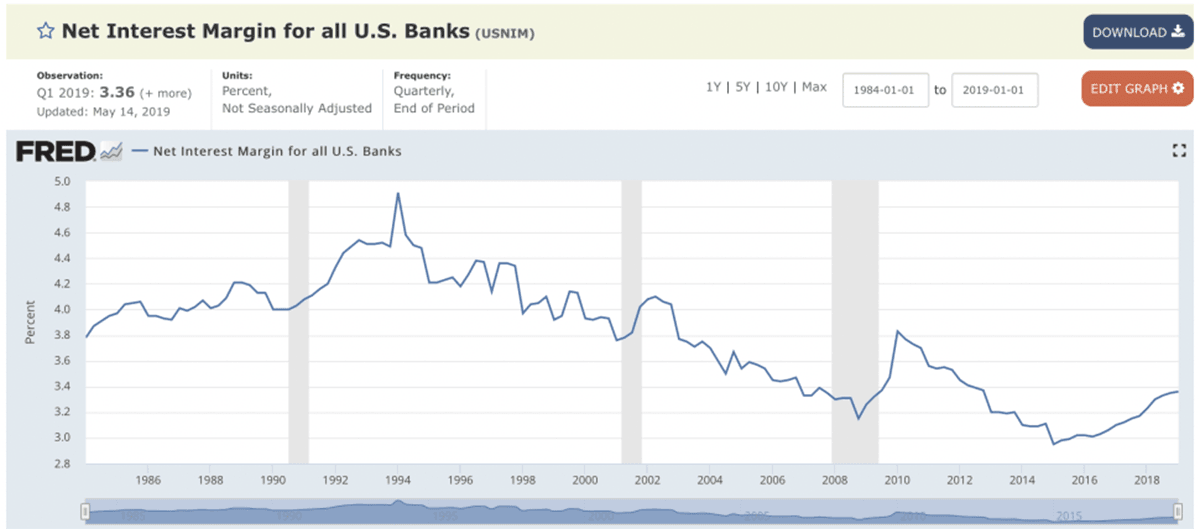

A bank’s net interest margin (NIM) is an industry metric that reflects this profit margin. NIM is simply the net interest income that a bank earns on its assets. It’s sort of a gross margin of a bank, where the interest collected is revenue and the interest paid is the “cost of goods sold”. Add the non-interest income and subtract all the operating expenses and reserves for bad loans, and you have a bank’s profit.

Here is a chart of the net interest margin of the US banking system going back to the early 1980’s:

Profit margins hit record lows back in 2015, just before the Fed began raising rates. The worry is now that rates will head back lower, and therefore profit margins will return to those all-time lows.

I’ll mention two simple thoughts as a possible counterpoint to the low rate fears.

First, banks earned record profits the same year their NIMs hit all time lows. Just like Walmart is one of the most profitable businesses in the Fortune 500 with razor thin margins, banks can earn lots of money with lower interest spreads if they make it up in the volume of total deposits they take and lend out or invest. Just as greater revenue can support lower margins at Costco, a higher amount of assets in the banking system can mitigate or offset the decline in net interest margins.

Second, the growth in assets in the banking system is about as predictable as anything in business. Money supply grows just about each and every year, and with it, so do bank assets, deposits, and net interest income. Basically, as people acquire more money (i.e. the economy grows), the banking system holds more money, and over time, earns more profits.

Here is a chart of net interest income in the US banking system in dollar terms over the past 37 years since rates peaked in 1982:

The net interest income (not the margin, but the aggregate profit) in the banking system has grown in 35 of the last 37 years, and just about every single year since 1934 when record keeping began.

I’ve mentioned before how predictable the deposit growth in the US banking system is (total deposits have risen every single year since the late 1940’s, without a single down year). Aggregate deposits grow each year, regardless of whether the economy is growing or in recession. With this steady dose of new funds, bank assets climb in lockstep, and so too does their ability to earn a profit on the spread of this greater supply of capital.

To sum this point up, profit margins (NIMs) will go up and down, but overall profit continues has risen each year since 1934 when the government began tracking this data. Regardless of whether rates and NIMs are rising or falling, banks have continually made more money over time. If you believe that our economy will be larger in 5 or 10 years, then it’s a near certainty that banking profits will be larger along with it.

And since Wells Fargo owns roughly a tenth of this banking system and given the sticky predictable nature of the banking business, I think it’s highly likely they’ll grab their piece of this incremental deposit growth.

I hope your summer is going well, and I look forward to writing again soon. Please feel free to reach out should you have any questions/comments.

Best Regards,

John Huber

Managing Partner, Portfolio Manager

Saber Capital Management, LLC