Kerrisdale Capital is short shares of Meta Materials Inc (NASDAQ:MMAT).

Q3 2021 hedge fund letters, conferences and more

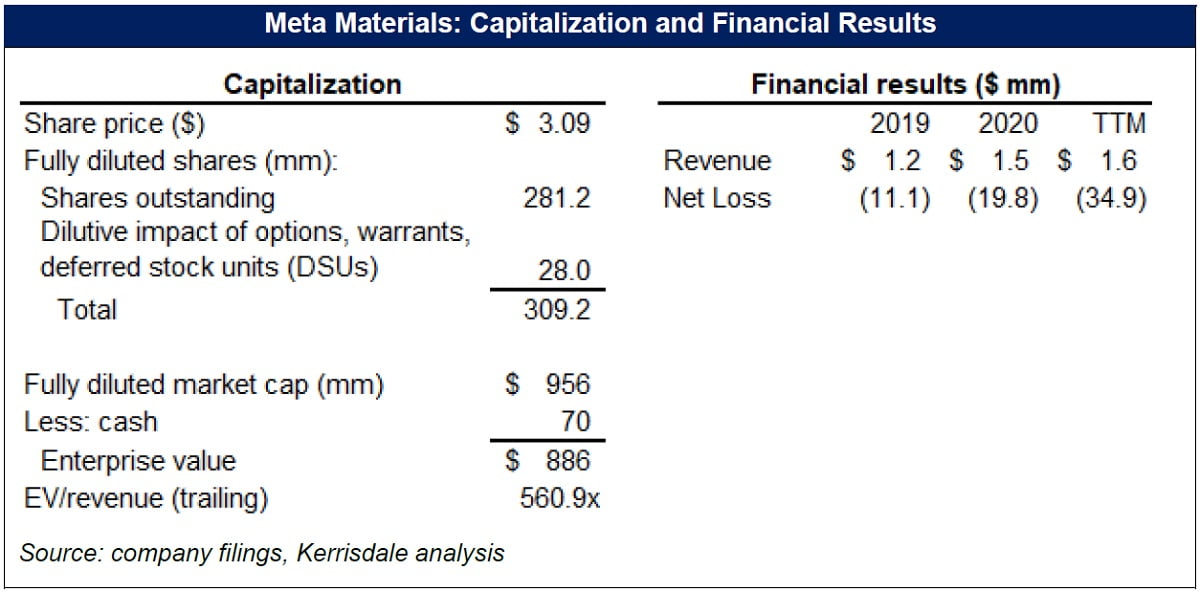

We are short shares of Meta Materials, a $1 billion market cap company whose business is comprised of a whole lot of nothing: no real revenue, no promising technologies, undeveloped products, no track record of achievement. The company is a collection of disjointed and failed laboratory experiments designed, in our opinion, to fuel a stock promotion scheme. From the archived records of Meta’s websites, public information concerning its finances and research activity, and the securities filings of recent years, a clear picture emerges: Meta has habitually made outlandish and misleading claims about the feasibility, development, and commercial potential of various technologies only to repeatedly move the goalposts or retrospectively alter its claims, often just quietly dropping entire projects they had previously touted as pivotal.

Founded in 2011, Meta first claimed it was developing transparent thin films (TTFs) for three end markets: solar cells, LED lighting, and laser protection. In the solar business, Meta started by pretending it could double solar cell efficiency, proceeded to deceptively use stock photos to depict products “in the final stage of development,” and then took investment funding from Lockheed Martin through a segment it later disclosed had already ceased activity at the time. Lockheed’s “investment” was booked as deferred revenue and conveniently accounted for 70% of Meta’s revenues between 2017-2020. Meta’s solar efforts are still portrayed on its website as “early stage” nearly ten years – and zero results – after they began, while the LED lighting business mysteriously disappeared in 2020. Like solar, there’s little evidence that a material business or notable technology ever existed.

Meanwhile, the laser protection segment does exist, but just barely. After six years supposedly developing laser glare protected (LGP) airplane windshields, Meta quietly scrapped the project in 2017, replacing it with less ambitious LGP glasses. These have been an abject failure, selling less than 100 units and $60,000 revenue in 4 years and proving Meta can’t scale production of even the simplest of films. Then there’s Meta’s “wireless sensing” segment, which stems from its questionable C$4.7 million acquisition of a UK-based medtech firm with zero revenues and negligible assets that was owned by Meta’s CEO and was promoting fake products, partly by misrepresenting the results of rudimentary biology experiments. Finally, Meta’s “lithography” segment is comprised of “NanoWeb,” a TTF technology it acquired in 2016 that remains in the same stage of development as in 2014. Multiple competing technologies have been commercialized in the interim while Meta has gone in reverse, terminating the licensure of a key patent, watching NanoWeb’s inventors resign, and acquiring another penny stock which it claims will synergize with NanoWeb, but which NanoWeb’s inventors told us is a distraction. Meta’s actions suggest management has no interest in commercializing NanoWeb and wouldn’t know how to if they tried.

Meta rose to billion-dollar status after agreeing to a reverse merger with defunct penny stock Torchlight Energy in December of 2020. The day it signed the deal, it appointed a CFO recently involved in an undisclosed paid promotion. In the ensuing 6 months, Torchlight’s stock twice rose exponentially in tandem with seemingly orchestrated social media promotion into perfectly timed equity offerings. The first saved Meta from insolvency. The second raised $133 million at a $5 billion valuation in just two days that coincided with a retail-frenzy-driven melt-up in its stock price. Meta then exploited the timing and quirky accounting of the reverse merger to disclose the unseemly details of the raise as opaquely as possible. Disappearing segments, misleading product claims, fake medical devices, research funding for subsidiaries that don’t exist, and circumstances so questionable around a penny stock reverse merger that it’s now the subject of an SEC Enforcement subpoena. It’s poetic that an optics company can be entirely made up of smoke and mirrors.

Company Background

Meta Materials (“Meta”) debuted as a public company just last year, when it participated in a reverse merger with Continental Precious Metals (CPM), a defunct Canadian miner relegated to NEX trading that had become a public-company shell in search of a merger partner. Earlier this year, Meta took part in its second reverse merger in as many years, combining with Torchlight Energy, another public shell seeking a reverse merger target. Currently sporting a $950 million market capitalization, it might come as a surprise that Meta’s business is comprised of, essentially, nothing.

Meta’s public company filings and website portray an “advanced materials and photonics company…seeking to harness the power of light” in three areas: holography, lithography, and wireless sensing. But as we discuss at length below, Meta’s three current “businesses” have generated just about zero product revenue over the last ten years despite continuously making grandiose product development claims. We expect this trend to continue given that the company has never actually commercialized anything.

To understand how a collection of primitive science experiments arrived at a billion-dollar valuation, it’s worth recounting the last decade’s worth of hype over which CEO George Palikaras has presided. By examining the ten-year track record of claims made by Palikaras and his management team, via Meta’s websites, financial filings, research papers, and other publicly available information, it’s easy to conclude that Meta repeatedly makes promotional and questionable claims about the viability, validity, promise, and even the existence of its technologies, only to abandon its previously hyped projects after some time passes.

Meta was founded in 2011 as Lamda Guard, an “advanced materials and systems engineering company…delivering nanotech solutions powered by metamaterials.” Metamaterials were described on the company’s website as “artificially created materials…microscopically built from conventional materials such as metals…[fabricated] to create novel devices with unprecedented and exotic properties.” Public records from the Atlantic Canada Opportunities Agency (ACOA) show that in 2012 the company received a $332,000 loan to work on transparent thin film (TTF) technology, and archives of the then-private company’s webpage from 2013 to mid-2017 highlight three corporate segments, each focused on developing transparent metamaterial thin films for a different application:

- Lamda Lux thin films would enhance the output and efficiency of LED lighting

- Lamda Solar thin films would improve the absorption of solar panel cells

- Lamda Guard thin films would be applied to aircraft windows to protect against laser strikes that could affect pilot vision

In mid-2016, Meta acquired a small TTF company called Rolith. Founded by a group of optical scientists in 2008, Rolith had prototyped a conductive TTF called NanoWeb that had potential applications in a variety of different fields, from touch screens to automobile windshields to transparent antennas. Having run out of cash and unable to secure any more funding, Rolith’s founders were forced to sell the company, and in mid-2016 struck a deal to sell to Meta for $2.5 million.

Two years later, in July 2018, Meta acquired London-based MediWise, “a medtech knowledge-driven company that empowers individuals to take control of their health.” In the press release announcing the acquisition, Meta boasted of MediWise’s “significant advancements in non-invasive glucose monitoring,” including its development of “a new product called glucoWISE, [which] has the potential to safely detect the concentration of glucose in the blood stream without having to draw blood or use test strips.” Strangely, the press release did not disclose that MediWise was approximately 50% owned by Meta’s CEO, Georgios Palikaras, and his wife. Nor did it mention the C$4 million purchase price, or the C$700 thousand intercompany loan that Meta had provided MediWise, and which was forgiven in the course of the transaction in addition to the purchase price. There was also no mention that glucoWISE didn’t actually exist or that MediWise had a negligible balance sheet and no record of any revenues. The deal, in retrospect, seems more like a bailout of a failed investment than a strategic acquisition.

Lamda Lux and Lamda Solar are now long gone, having mysteriously disappeared from Meta’s website after its first reverse merger in 2020 with Continental Precious Metals. We can’t find any evidence that either division has ever successfully produced so much as a single prototype and, as we describe below, we believe that Meta’s presentation of its Solar and Lux segments was highly misleading. Meta currently describes itself as comprised of three new segments, which we explore at greater depth in what follows:

- Holography – this is the old Lamda Guard, which underwent a strategic pivot, redirecting its efforts from TTFs for aircraft windshields to “holographic” laser glare protection (LGP) glasses, which have followed the typical Meta path from hyped technology to abject failure.

- Lithography – the segment dedicated to NanoWeb development, except there hasn’t been much in the way of development. In the 5+ years since the Rolith acquisition, an array of competitive conductive TTF alternatives have been developed, commercialized, and mass produced, while NanoWeb has remained in the same stage of commercialization as in 2014. Meta also ceased licensing from the University of Michigan a patent critical to the NanoWeb production process, which suggests that Meta is either not really invested in commercializing the product, or that it doesn’t know how to – or both, considering that Rolith’s founding scientists left the company within two years of its acquisition by Meta.

- Wireless Sensing – this segment houses the MediWise acquisition and is ostensibly working on the same exact projects that MediWise was working on 7 years ago, all of which sound like they emanate from a science fiction novel. Most prominently, this subsidiary is (still) developing a “non-invasive glucose monitor” using a mechanism that the clinical literature suggests is actually impossible.

Before assessing whether there’s any commercial substance to these segments (in short: no), it’s instructive to examine the quiet failure of Meta’s early technological forays and the creative ways Meta was able to finance a façade of scientific accomplishment with no legitimate underpinning.

Read the full report here by Kerrisdale Capital