Those who own gold often argue how to best own it. I encourage anyone holding gold to assess the pros and cons of different choices of gold ownership to make an educated rather than emotional decision. Let me explain.

I commissioned the above cartoon back in 2011 in response to an assertion by CNBC’s Steve Liesman no one would accept a gold coin in a grocery store. My take was that, hell, if I offered a gold coin, I’m pretty sure I would find a taker if I wanted to exchange it for some groceries.

There appears to be an eternal back and forth between those that “love” and those that “hate” gold; that discussion, in my humble opinion, misses the point. It is striking how this shiny metal raises emotions by both friends and foes. Maybe it is because gold is so simple, so pure, the fact that there are fairly few industrial uses for it, that emotions take over in discussing gold’s merits.

The historic context matters. Gold has been used as money for millennia; yet some say it is a “barbaric relic” preferring to use fiat currencies for commerce. All major currencies are fiat currencies these days, that is, they can be created ‘out of thin air’, by the stroke of a keyboard at a central bank. The modern world of fiat currencies, is in place in its current form since 1971 when Nixon ‘temporarily’ abandoned the last link to gold. The very notion of currency has been used in new ways as promoters of virtual tokens subject to a decentralized creation and sharing methodology referred to as crypto-currencies have touted that they will disrupt the way we transaction and store value. The value of crypto-currencies, of course, has been highly volatile, and none of this should be construed as an investment recommendation. Crypto-currencies, in my humble opinion, are as much of a currency as anything one can trade. Indeed, when a publicly traded company acquires another firm, management offers their share prices as a currency.

One might be excused to think that a currency is something with a stable value. Scanning through my past writings, I see references as far back as 2008 where I argue that there may be no such thing anymore as a “safe” asset, and that the U.S. dollar may have lost its function as a store of value. Indeed, I have argued in the past and still believe, one can construct a portfolio without a safe asset, as in modern portfolio theory. In this context, it may be a petty contest to argue one thing is a better currency than something else. Yet I would think all these so-called currencies are different in various respects.

Gold is often criticized for not generating income. However, your twenty-dollar bill in your wallet doesn’t generate income either. When you deposit $20 in your bank account, you might earn an income, but note that you’ve converted your twenty-dollar bill, a liability of the Federal Reserve, into a loan to the bank. Differently said, you are putting your $20 at risk. With FDIC insurance, that notion of risk gets socialized (meaning the government guarantees FDIC insured deposits), but the concept holds, especially when deposits are large. Similarly, you can earn an income with gold by leasing it out, i.e. putting it at risk. That’s because when you lend someone gold (and presumably earn an income for doing so), you risk that the counterparty won’t be able to return the gold back to you at the agreed time.

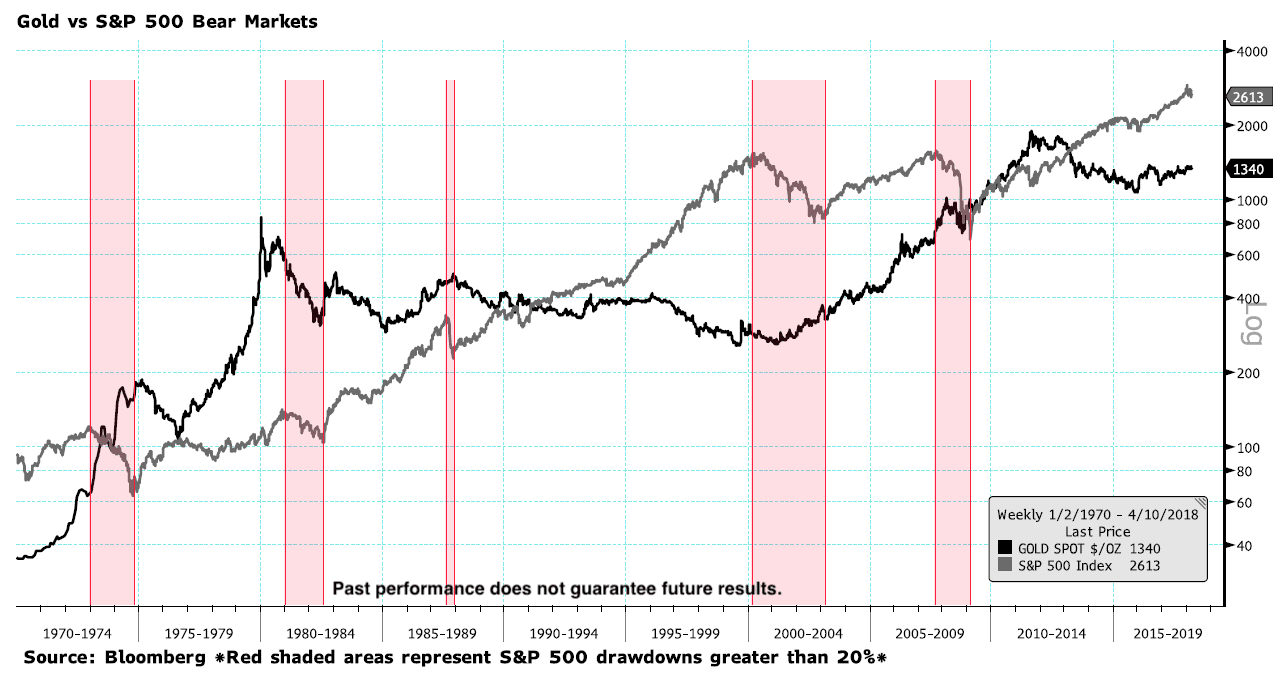

That said, what attracts many to gold is that, in the words of former Federal Reserve Chairman Greenspan: “Gold has always been accepted without reference to any other guarantee.” More broadly, because gold in itself is not the obligation of anyone else, it is not considered to have counterparty risk; counterpary risk, of course, is the risk that a party to a contract won’t live up to its contractual obligation. While gold is “consumed” by jewelry demand, it is indestructible. The price of gold, just like anything else, is subject to the forces of supply and demand. Yet I would argue that those supply/demand dynamics are simpler than those of many other assets, especially those generating income. The fact that gold doesn’t have inherent cash flow also makes it a natural diversifier to be considered in a portfolio to assets that do have a cash flow. That’s because when volatility rises, future cash flows may be discounted more; as a result, in my analysis, since 1970, the price of gold has historically outperformed risk assets in bear markets (defined as 20% declines from a market top) in the stock market (a notable exception was the early 1980s when the price of gold declined as then Fed Chair Paul Volcker increased interest rates substantially):

After a nine-year bull market, those who have taken precautions against a market decline are often ridiculed; how ‘dumb’ they must be that they weren’t fully invested. With due respect, this is a bunch of garbage. Investing isn’t about beating an index, it is about managing one’s savings in the context of one’s objectives. And if you are more comfortable to have safety in the form of x, y or z, no matter what that may be, then that is as important as some computer model that suggests a different form of investment should yield a given return.

The argument for a diversified portfolio is because the portfolio, as a whole, may provide a better risk-adjusted return than any single investment. But odds are that there will always be that one spectacular investment that will “outperform” others. By that argument, we should all play the lottery, as, clearly, you can win millions. It doesn’t take a rocket scientist, though, to realize that the odds of winning those millions are miniscule and most lose 100% of their “investment” into a lottery ticket. Yet the lottery winner gets all the attention. Similarly, CNBC touts the winners of yesterday in the stock market. In this sense, I don’t think it makes too much sense to argue for or against any one investment; it’s the totality of one’s portfolio that ultimately matters.

There are those that want to have their cake and eat it, too, notably they want to take advantage of perceived advantages of gold ownership, but want to have more potential upside should the price of gold increase. I’m talking about buying gold in the ground through investments in gold miners. The basic idea is that the cost of mining is reasonably fixed, thus causing earnings to move up disproportionally should the price of gold rise (let’s say the price of gold is $1,300; the cost of mining is $1,000. Should the price of gold rise 10% to $1,430, the earnings of the gold mining company increases 43.44% to $430 from $300 if costs remain unchanged). In practice, it’s more complicated than that. In the run-up in the price of gold in the years leading up to 2011, the value of many gold miners didn’t keep up with the rise in the price of gold. Many reasons could be cited; one of them was that costs were not constant as not only the cost of energy rose (it takes a lot of energy to mine gold), but all stakeholders, including workers that demanded higher wages and governments that charged higher taxes, wanted a share of the pie. Small, so-called junior miners, may be highly speculative bets that they strike gold. In 2008, it became painfully clear that those firms were highly dependent on access to credit. As such, investments in miners should be assessed in the context of the totality of the risks they pose, as investors should also consider management risk, regulatory risk, credit risk, to name a few. Large, established mining companies have their own set of risks; for example, until not long ago, we believe some of the larger mining companies had a greater interest in increasing ounces of gold they owned (meaning they acquired other mining firms) than in maximizing earnings. None of this means mining companies are good or bad investments, but that investors need to do their homework and recognize the risks are very much more complex than the risk of gold ownership.

Regulatory risks also extend to physical gold ownership. From April 5, 1933, through December 31, 1973, President Roosevelt’s executive order 6102 banned the ‘hoarding of gold coin, gold bullion and gold certificates within the continental United States.’ Given that the U.S. dollar is no longer backed by gold, one could argue any concern that such a ban could be re-introduced may be overblown, but history shows the concern has merit. I look at my investments in terms of risk scenarios, and while I personally do not think a renewed banning of gold ownership is likely at any-time in the foreseeable future, it is a probability greater than zero nonetheless.

Yet, just as with any other investment, we do have to ask ourselves what we are trying to achieve with it? Different investors own gold for different purposes; they may also own varying percentages relative to their investment portfolio; each investor’s situation is, quite likely, different. Just as regulations do not allow me to give specific investment advice in a public forum because it is impossible to know the specific situation of everyone reading this, it makes little sense to insist there’s only one way to own gold.

A word about counterparty risk

The biggest drawback I see in owning physical gold in your home is the risk of loss. Hiding it so well that you forget; it wouldn’t be the first time that a future homeowner finds gold in the attic or wall. Then there’s the risk of theft. Once you buy gold, do you have to buy a rifle as well? Here’s the thing: the beauty of gold is that it doesn’t have any counterparty risk; however, the moment you touch it, you introduce counterparty risk. It’s for that reason why many don’t want to hold their gold with a bank. However, many don’t consider that this doesn’t eliminate the risk of physical loss. You choose your evil, and depending on your circumstances, different solutions, or a diversified approach, might be appropriate with regard to how you hold gold.

This, of course, doesn’t just apply to gold. If you hold all your money with one bank, what about if you own more than the FDIC insured amount? What about stocks? Do you have everything you own with the same broker, and do you know what were to happen to your stocks if your broker went bankrupt?

In the post 2008 era, it became more popular to spread one’s assets to multiple custodians. However, in my analysis, that trend has gone into reverse in recent years. If you look at institutional investors, the cost of doing business has gone up dramatically in recent years, forcing many to cut back the number of custodians (or prime brokers) they use. For prime brokers – this is where hedge funds, amongst others, historically keep their assets so they can borrow cheaply against them to gear themselves up – it has become very expensive to provide capital to speculators, thus passing along costs. Regulators’ frenzy to make the financial system safer may well have had the opposite effect, that is, to concentrate the risks in fewer places. Indeed, European regulators blocked the merger between two clearing firms last year as they cautioned about too great a concentration of risk amongst others.

Differently said, you do not have to be a gold bug to have legitimate concerns about potential counterparty risks.

Gold in a safety deposit box

Some argue against holding gold in a safety deposit box in a bank due to the aforementioned risk that the government might ban gold ownership. Some say you have to own your gold abroad and are often quick to add Switzerland is the place to store it. Yet, Swiss banking secrecy and rules has more holes than Swiss cheese, with regulations having changed numerous times over the past twenty years. Singapore has come up as the right place in Asia, yet is a country that’s so tiny that it could be overrun militarily the right place. What about China? Will you entrust the communist government with your gold? Luckily, everything is better up North, oh Canada! There was a time the blogosphere fell in love with some Canadian gold trusts, partially because of their simplicity. Yet, upon closer inspection, some of those trusts were (and some still are) more actively run businesses rather than passive trusts (passive trusts do not engage in hostile takeovers, for example); in any case, the “simplicity” of some Canadian entities may be more due to a different legal environment and lax regulation rather than truly being safer. Similarly, there are shoebox enterprises in Switzerland that offer to store your gold; upon closer inspection, we have seen some of them not adhere to local regulations, but they are so small that they fly under the radar.

Personally, I own gold for several different reasons in a variety of different ways. My criticisms of some choices of holding gold do not suggest that I object to holding gold in any particular way. As indicated, just as diversification applies to a prudent portfolio, I believe it is prudent to be aware of the pros and cons of any one way of holding gold.

Money in a crisis

The concept of safety is in the eye of the beholder. During the financial crisis, we were concerned about the return of your money rather than the return on your money. The price of gold may decline; but if you own a certain number of ounces, physically in gold coins, the number of ounces will not decline unless you sell the gold, lose it or have it stolen.

Coming back to the cartoon, should the financial system ever break down, will you have money? Do you even need money? Do you scoff at that possibility? Let me make it clear that I do not think the financial system is about to break apart. That said,

- In 2007, I started to get very concerned about the stability of the financial system. As the trio of former Fed Chair Ben Bernanke, former Treasury Secretary Hank Paulson and former New York Fed President (then Treasury Secretary) Timothy Geithner confirmed in a recent interview with public radio’s Kay Ryssdal that the situation was dire in late September and October 2008. I took out a substantial amount of cash and physical gold ahead of those most volatile days. It’s nice to know the financial system didn’t break, but I preferred to have a plan B in place, just in case.

- I recently finished reading Niall Ferguson’s The Square and the Tower, a fascinating read. Not so great is that he cautions the world might plunge into anarchy and chaos should we not find a way to impose structure on today’s networked world (the bad guys also network). He provides lots of food for thought, including suggestions how bad outcomes can be mitigated. But, again, should we leave it up to policy makers to do the right thing, when it is those in power that might get dethroned?

In both of these scenarios, let’s assume for a moment that a truly bad scenario really unfolded. Should the wheels come off, is it more important to be in a safe community, to be able to live off one’s land? To have a few gold coins?

As you might gather, you ask ten people and may well get ten different answers. History has shown that human beings aren’t all that good at predicting how they will behave in a crisis. The story of the Three Little Pigs suggests that many laugh at those that take precautions, only to come and seek help when disaster strikes.

Gold as an investment

To me, there’s a difference between gold as a potential emergency supply and gold as an investment. That said, the latter might of course morph into the former. Regardless, some argue that even larger amounts of gold should be held in physical form outside the banking system. There are advantages and disadvantages to that approach. The biggest advantage I see is what others consider a shortcoming: the reduced liquidity of physical gold outside the banking system. If you own gold coins or bars, they are easily converted into cash should you chose to do that, but the transaction costs are higher than if you held your gold through some electronic ledger, say through an exchange traded fund in your brokerage account. Importantly, you may be less tempted to trade: when you look at a physical bar of gold, you will always see the same bar (number of ounces) in front of you; if, in contrast, you hold it in your brokerage account, you will see the daily price swings as the price of gold may be jumping at you on the screen on a tick-by-tick basis.

In that sense, physical gold in your possession is similar as a painting or even a home you own: very few people day trade those physical possessions. The price of anything you physically own, of course, still fluctuates, and may go up or down.

Gold is beautiful

Some own gold jewelry because it is beautiful. When it comes to jewelry, there aren’t heated debates as to why someone owns jewelry rather than, say, a painting. Are collectors of beautiful things more civilized than investors that quibble over owning gold versus stocks?

That said, millennials are said to prefer experiences over things. Have times really changed (youngsters don’t wear golden watches anymore) or is it that we try to come up with a new paradigm now that many don’t have the money anymore to splurge on expensive gadgets?

Do we buy jewelry because we love it (or love the person we give it to)? Do we buy it because we believe it will hold its value or appreciate? Do we care about the markup above the price of gold (which can vary from a small premium to a high multiple depending on the perceived ‘value added’ by the artist)? Do we buy it to have something of value outside the financial system?

Conversely, are we concerned about theft, losing or destroying it? Are we concerned about getting scammed by a con artist selling something as gold that really isn’t (remember those street vendors on your last vacation)?

Coins for the collector

Robert Mish, a Menlo Park gold dealer, knows more about numismatics than anyone I know in the industry. I sometimes stop by his shop to get a sense of what investors in coins are looking for. He used to tell me that customers would bring in coins from their home country (or home country of their parents) to raise cash. Those coins tend to be more valuable in their country of origin; as such, one way for coin dealers like him to earn money is to then sell those coins in those countries. He would bring to life stories that gold travels to the countries where wealth is building.

I am not a collector of rare coins as I am not an expert in the field. It takes a lifetime of experience; that, of course, makes it attractive to those who are experts.

Gold ETFs

These days, investors have a variety of ways they can invest in gold through their brokerage account. Yet, they are not all created equal. Some offer some sort of deliverability, although those mechanisms also vary. As many readers may be aware, I took investing in gold to a new level by studying the various gold investment vehicles in great depth, then opting to launch one myself. Known these days as the VanEck Merk Gold Trust (NYSE:OUNZ), we call it the deliverable gold ETF. It took us over three years and considerable expense to develop this ETF. There were two main reasons the development took that long: one is that we wanted to do it right; the other was that we broke new ground by facilitating delivery in a scalable way.

Doing it right is more easily said than done. As discussed herein, there are pros and cons with any form and location of holding gold. What works for one person may not be suitable for another. That said, I had owned gold in several different ways, including gold ETFs, but had read criticisms of other structures, including the one I invested in. At some point, I had my team dig through the criticisms in the blogosphere, as well as scout through prospectuses. I learned that criticism comes cheap, meaning that many bloggers do not fully understand the products they criticize. That said, a variety of fair points were raised. I opted to visit numerous vaults and learned that not all vaults are created equal. I also dived into what, at the time, I considered the conundrum of tremendous distrust between the institutional and retail world. While it is no secret that many in the blogosphere don’t like banks, the banks, similarly do not want to have anything to do with retail. To the casual observer, the retail public is content in owning coins, whereas institutions deal in so-called London bars.

London bars are gold bars with comparatively low purity, a minimum purity of only 95%, as well as varying sizes between 350 and 430 troy ounces. Gold coins and other bars generally have a fixed weight and purity. The reason London bars have wider guidelines is that they are easier to produce. When someone quotes the price of gold, it is usually the price of London bar in London. While the standard is comparatively loose, London bars produced today often have a much higher purity than 95% (the value of a bar is determined by its net gold content). In order to avoid the cost of re-assaying a gold bar each time it changes hands, the London Bullion Market Association (LBMA) has established a set of so-called Good Delivery guidelines.

By agreement, all Good Delivery gold is equivalent, valued based on its gold content, with a potential price deviation if delivery is not in London. But in practice, as indestructible as gold is, some bars look better than others. Imagine you manage a vault and receive a Good Delivery bar from a central bank that looks like it has seen better days. Rather than alienating your client (you like to keep a central bank as your client), such bars are often sent to the refinery; and possibly turned into kilobars or some other bars that trade at a premium to the London bar price; that process pays for the recycling of the gold. The types of vaults that offer such services tend to be banks that have their own inventory of gold. They may also use the custody fee to recycle gold into freshly minted London bars.

In my view, the key reason there is so much distrust between the institutional and retail world is that the institutional world is simply not equipped to deal with retail. When I first approached institutions and told them I am looking to structure a gold ETF that also facilitates delivery of gold, they saw red flags everywhere. Specifically, large institutions are not equipped to do anti-money laundering checks on their clients. Instead, large institutions have a limited number of other institutions as their clients, meaning a limited number of clients they can do their due diligence on. It dawned on me that building an interface between those two worlds had not been done; at least it had not been done properly. The way I looked at it, it isn’t good enough to do due diligence on the rare investor that might want to take delivery. No, a process must be robust enough so that should there ever be a rush to request delivery, institutions won’t balk. We had talked to a vault (outside the banking system) where one of our competitors vaults its gold and were told they would kick us out if a larger number of investors indeed were to take delivery. That was not the way we wanted OUNZ to work. We wanted a deliverable gold vehicle that’s scalable, notably one that allows many investors to request delivery should there ever be a surge for this option. Not only did we devise such a process, we were granted a patent on it (U.S. patent #8,626,641). If others offer deliverability, you might want to double check whether their process is designed to handle a larger volume. If it does, well, let us know, as our analysis shows a license for our patent may then well be required. We developed several Guiding Principles, including

- Holding London bars;

- Maintaining allocated gold. That is, physical gold is held in a segregated form in the name of OUNZ. OUNZ has full title to the gold with the custodian holding it on behalf of OUNZ. Each investor owns a pro-rata share of OUNZ, and as such holds a pro-rata ownership of OUNZ’s assets. OUNZ holdings are identified in a weight list of bars available to the public at merkgold.com;

- Permitting investors to take delivery of physical gold. As London bars are impractical for retail investors, we facilitate an exchange into other coins or bars (there are fees involved). Importantly, though, because investors already own the gold, taking delivery in itself is not a taxable event (this isn’t tax advice; please read the prospectus for details). If you invest in another entity that allows delivery, have a closer look and inquire about the tax consequences.1

We started out looking at institutions outside of the banking system. The main challenge in working with them is that they have a difficult time working with the settlement periods of an exchange. Under no circumstances did we want to issue shares in OUNZ without confirmation that the gold has been allocated by the custodian. In fact, if you read the objective of OUNZ and compare it with those of other gold ETFs, you will notice a subtle difference:

The Trust’s primary objective is to provide investors with an opportunity to invest in gold through the shares and be able to take delivery of physical gold bullion (physical gold) in exchange for their shares. The Trust’s secondary objective is for the shares to reflect the performance of the price of gold less the expenses of the Trust’s operations.

That is, while OUNZ has historically tracked the price of gold very closely and has had a spread between bid and ask price of OUNZ shares of only 1 cent almost all the time (around major economic news it, the spread does widen a bit at times, just as the spread widens for spot trading of gold), we are firmly committed to enabling investors to own gold; the tracking of the price of gold is a secondary objective. This means that if for whatever reason gold may not be available when demand surges, we rather have the price of OUNZ deviate from its net asset value than to accept unallocated or so-called paper gold. The maximum amount of unallocated gold OUNZ may possess at the end of any business day is 430 ounces which is the maximum size of a London bar (this is required as no partial bars cannot be allocated gold).

Let’s talk insurance for a moment. There are some programs that charge nothing to store unallocated gold. We caution that there is no free lunch; unallocated means that the gold is the liability of the institution where the gold is held. You then may want to check the creditworthiness of the institutions. Take the Perth Mint, for example. It is owned (“guaranteed”) by the Western Australian government, i.e. a regional province of Australia that as of this writing has a credit rating of Aa2 by Moody’s and AA+ by S&P. We don’t have an investment recommendation on them, but would like to point out that I believe a key reason why many investors want to own gold is because they want to minimize counterparty risk. It may, of course, be worth it to some investors to reduce or eliminate fees in return for taking on some risk.

In case of OUNZ, we looked at many possible places to have the gold vaulted. We looked both inside the U.S., as well in Canada, UK, Switzerland and others. We looked at vaults inside and outside the banking system. We ended up choosing a London based bank because, in my assessment, they were the most appropriate. Importantly, London has a long history of gold trading and storage; in London, allocated gold isn’t merely a buzzword. We don't think it is a coincidence that the vault we chose does not have employees steal gold in their underwear (yes, that’s a jab at another gold vault – google it, if you are so inclined). If you read OUNZ’s prospectus carefully, you will see that we can instruct the trustee to move the gold to another vault should we deem it appropriate to vault the gold elsewhere.

Aside from separate auditors for physical and financial audits, I also have inspected the gold each year myself.

I don’t suggest everyone spend three years to figure out where to best vault their gold. Indeed, quite a few may shrug off this entire debate and say, heck, the only place I keep my gold is at home or some undisclosed location outside the banking system. I wasn’t comfortable holding considerable amounts of gold at my home. I also had another motivation: I was holding gold in an investment fund I manage and was looking for what I believe was a more appropriate way of holding it. Financially that might not have been the smartest move as our management firm was (and still are) waiving the fees of owning OUNZ in the fund, so that it cannot be said that I’m charging fees twice; in practice, of course, there is considerable cost in vaulting the gold, and I would earn more money if I opted to hold the gold through an unaffiliated vehicle.2

How I own my gold

I own much of my gold through OUNZ, but also have significant gold holdings in both coins (mostly Canadian Maples) and bars (mostly kilobars). Through OUNZ, I own gold in London; I also own gold in Switzerland and the U.S.; I own gold in safety deposit boxes. Please don’t think of robbing my home, as I do not usually store gold coins and bars there.

We will expand on the discussion above, notably touch a little more on why to hold gold at our upcoming quarterly webinar; please register to join me at our Webinar on Wednesday, April 18, at 4:15pm ET. Please consider sharing this analysis with your friends.

Axel Merk

Merk Investments, Manager of the Merk Funds

1) I shudder when I look at the tax implications of owning gold in some entities. In one of them that shall remain unnamed, investors may take delivery, but if they do, not only do they have to pay taxes on potential gains, but all other investors may also get slapped with a tax bill. Most don’t notice because the vehicle is not tracking the price of gold, and the entity is paying the tax bill.

2) For regulatory nerds: it is our understanding that, technically, we would be allowed to ‘double dip’ because OUNZ is a trust holding gold, not a security; as the regulation against ‘double dipping’ only applies to securities, we are not required to waive the fee.