The threat of a U.S.-led global trade war has exposed the earnings vulnerability of many global equity indexes. Bank of America, U.S. Trust analyzed 18 different international indexes in a new report and the results are quite telling. The U.S. ranked in the top three markets in terms of total revenue generation per each index — underscoring America’s commanding presence when it comes to global top-line growth. The region most dependent on the U.S. for revenue growth: Europe.

Q2 hedge fund letters, conference, scoops etc

Understanding the geographic revenue exposures of companies and global equity indexes is especially important for investors positioning portfolios in an environment of trade policy uncertainty. Whether it’s a Japanese auto maker selling a car in China, a British pharmaceutical company developing products for the U.S. market, or a Swiss bank providing financial services for Asian investors, the global activities of multinational companies are more complex than traditionally thought. Companies’ revenue exposure to different consumers around the world is more important than where they are domiciled.

Global Revenues: Many Roads Lead to the United States

The rise of China, the economic heft of the European Union, the burgeoning middle classes of the emerging markets—despite the economic importance and potency of each one of these cohorts, the world still largely beats to the tune of America.

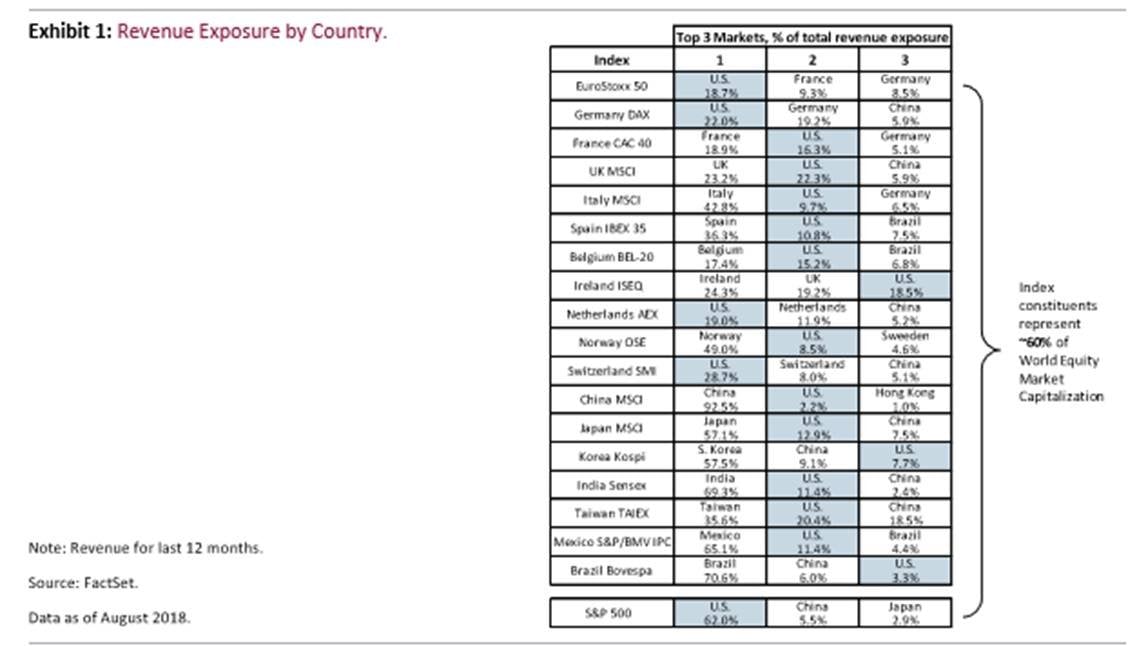

That’s all too evident from Exhibit 1, which ranks country revenue exposure for major stock indexes. We aggregated data on 18 different international indexes (with a wide geographic profile), and the results are quite telling: per each index, the U.S. ranked in the top three markets in terms of total revenue generation, underscoring America’s commanding presence when it comes to global top-line growth. Take the German DAX, for instance, comprising 30 of the largest publicly traded German stocks. According to the latest figures, almost one quarter of revenue earned from Germany’s largest companies is derived from the United States, followed by Germany and China, a distant third.

Large cap Germany, in other words, is highly leveraged to the United States, as are other European nations like France, the United Kingdom, Belgium, the Netherlands and Switzerland. Switzerland is the most exposed to the U.S., with the U.S. accounting for nearly 30% of total revenue of the Swiss Market Index (SMI). The least leveraged: Italy and Norway, with the U.S. accounting for 9.7% of total revenue in the former and just 8.5% in the latter. Of Europe’s largest companies, represented by the EuroStoxx 50, note that nearly one-fifth of total revenue comes from the United States, more than double the exposure to France (9.3%) and Germany (8.5%).

Against this backdrop, domestic earnings are secondary for many European equity markets, with the proportion of revenue generated domestically under 25% of the total in such nations as Germany, France the United Kingdom, Belgium, Ireland, Switzerland and the Netherlands. European revenues are highly globalized, in other words. And juxtaposed against a strained global trading environment, as well as rising foreign direct investment barriers and increasing U.S. trade protectionism, it’s little wonder that many of Europe’s main indexes have emerged as global laggards this year. To this point, while the S&P 500 is up 7.2% year-to-date (total return), Germany’s DAX has underperformed, falling 3.8% since the start of the year, in local-currency terms, and 8.8% in dollar terms.

In Asia, the region’s earnings exposure to the United States is not as great as Europe’s, although setting aside domestic revenue, the U.S. ranks as the most important foreign market for revenues for firms from China, Japan, Taiwan and India, according to FactSet. In Latin America, Mexico and Brazil are overwhelmingly oriented toward the domestic market, although Mexico’s exposure to the U.S. economy is borne out more by crossborder trade and investment than by corporate revenue. This same dynamic holds sway in China, where, according to FactSet revenue data on the China MSCI index, domestic sales account for over 90% of total revenues, with the bulk of Chinese firms leveraged to the massive local market. The linkage and exposure to the U.S., however, comes via trade and the need for intermediate parts and components for final assembly. Indeed, this reliance on intermediate trade in goods and China’s position as the primary U.S. target in a trade war have contributed to the weak performance of Chinese equities this year. Other trading partners in the Asian region at risk from a reordering of global supply chains have also underperformed, while Indian equities, relatively unexposed to the trade war, have remained resilient.

As an aside to all of the above, since the indexes shown above vary in terms of number of constituents, market cap of securities (large cap vs. mid cap) and sector allocation, differences in global revenue exposure may arise. For instance, Germany’s DAX, which focuses on a subsection of large multinationals, naturally represents some of the most globally exposed companies in the country. Meanwhile, the MSCI indexes listed above, which consist of both mid cap and large cap companies, could be more domestically driven. However, after comparing across indexes, we believe this impact to be relatively minor.

In terms of overall asset allocation, understanding the geographic revenue exposures of companies and global equity indexes is especially important for investors positioning portfolios in an environment of trade policy uncertainty. Whether it’s a Japanese auto maker selling a car in China, a British pharmaceutical company developing products for the U.S. market, or a Swiss bank providing financial services for Asian investors, the global activities of multinational companies are much more complex than traditionally thought. Thus, traditional diversification methods—whereby investors allocate funds according to company domicile—can be misleading. Companies’ revenue exposure to different consumers around the world is more telling and important. Understanding these exposures is critical for portfolio positioning and diversification.

The Multiple Levers Of The U.S. Economy

All of the above underscores the fact that when it comes to trade skirmishes between the United States and the rest of the world, the United States enjoys considerable leverage. It’s America’s large and wealthy consumer market, along with the U.S. dollar’s global reign, that gives the United States so much economic punch relative to the rest of the world. Per the former, no market in the world—including China—offers foreign countries and companies as much commercial opportunity as the United States, home to less than 5% of the world’s population yet 29% of total global personal consumption. The U.S. consumer remains one of the most potent economic forces on earth—and a key source of revenue for firms around the world.

Similarly, for decades, no market in the world has been as open to foreign competition as the United States, home to some of the lowest general tariffs on trade on the planet. The latter is by design since liberal crossborder trade and investment regulations have long suited America’s consumption-led economy. The lower the tariffs on imports, the lower the cost of foreign goods and services to U.S. consumers and the more the choices of goods from which to choose—and the greater the revenue opportunity for firms from Germany, France, Japan and others. The U.S. remains the world’s largest importer, accounting for 13% of total global imports in 2017.

Beyond America’s sizable and wealthy consumer market, the nation’s pre-eminent geo-economic lever is the U.S. dollar and the fact that the global financial architecture pivots on the greenback. While the world can do without many currencies, it cannot survive, at least for now, without the greenback. The U.S. dollar is the primary grease of global commerce, lubricating virtually every foreign transaction, every day of the year.

Think of the U.S. Federal Reserve, the Department of the Treasury, and Wall Street as the financial plumbers of the global economy. The global payments system runs on dollars and is routed through the canyons of Wall Street, giving Washington tremendous leverage to deny virtually any foreign country or company access to U.S. dollars. And being without dollars is like being without oxygen—you cannot function or survive for long.

In the end, there is a reason the S&P 500—notwithstanding all the daily headline risks—is up over 7% for the year (total return), trading just 1.4% off its all-time high, and outperforming the rest of the world. In addition to solid U.S. economic growth, strong earnings and corporate tax reform, the markets sense that in an unfolding environment of trade and investment restrictions, the world has more to lose than the United States does. The threat of a U.S.-led global trade war has exposed the earnings vulnerability of many global indexes. When it comes to global revenue, much of the world beats to the tune of the United States.