Intangible assets comprise the bulk of corporate value, yet methods for measuring management’s performance generating value through them scarcely exist.

Some things are difficult to understand and measure. Space, for example, is incredibly vast. So when astronomers try to measure the distance to objects in space, they construct cosmic distance ladders. A cosmic distance ladder is a collection of techniques including trigonometry, standard candle brightness, Cepheid variables, the Hubble Constant, and parallax, that are used to measure distances to objects. Essentially, scientists layer measurements they do know to figure out what they don’t know.

Q4 2019 hedge fund letters, conferences and more

Invisible Assets

Any investor who subtracts the Book Value from the Market Value of their favorite company will quickly discover that most of the business’s worth doesn’t show up on financial statements. The swelling value of intangible assets has been propelled by a huge shift in the economy, one that favors idea development over production prowess.

In a strategic transaction, like a merger or acquisition, intangible value is thrown into a catch-all bucket called goodwill. Still, “goodwill” does not recognize internally created value. It is a term used to explain the difference between book value and acquisition price in a transaction. So it’s a measure of the price paid for externally generated intangible value. While it identifies cost, it won’t help investors understand how companies generate value through intangible asset performance.

According to intangible asset consultancy Ocean Tomo, today the ratio of intangible value to tangible book value is about 87%, leaving a meager 13% of corporate value visible on the books. That means a lot of value is unaccounted for. It’s not a coincidence that when you think of trillion-dollar companies like Microsoft Corporation (NASDAQ:MSFT), Alphabet, or Apple, most of their value is intangible. Tangible assets like plants, property, equipment, and inventory represent only a tiny sliver of their worth.

Management Performance

Most corporate value resides in intangible assets, so the companies that invest in intangible assets wisely will outperform others. So how do investors identify such companies when there are few measures of intangible assets used today? When it comes to their investments, investors tend to be concerned with transparency and performance. Most will choose performance over transparency. That’s good in this case, because transparency can be the enemy of intangible investment.

Intangible asset value is developed through specific intangible investments. This is the capital allocated to things like talent, R&D, advertising, distribution, and partnership channels. Some companies will rightly argue that there are some intangible investments that should be invisible. Modern companies invest in ideas and that makes transparency problematic. Clearly, broadcasting details about (or having auditors scrutinize) investments in R&D or intellectual property would be competitively unwise.

Strong Brands Make Intangible Assets More Valuable

Brand is the largest subcategory of intangible assets, representing 14-21% of corporate value. Strong brands make intangible assets more valuable. A strong brand is critical to leveraging the full value of your intangible assets. If your neighbor develops a new 6G mobile phone it’s interesting. If Apple develops a 6G phone, it’s valuable. The moat around Apple is deep and the company can demand a steep premium on its products and services.

Companies build brands through branded investment in specific areas, like R&D, customer support, design, advertising, marketing, and sales. Some companies build brand consciously, others don’t. Maybe that’s because building brand value is tricky due to its treatment by finance and accounting.

Accounting Rules Say Rockets Must Be Built In-Flight

Brand building is a budgeted function typically owned by marketing. So marketing must use its fluctuating annual budgets to build a long-term legacy, as if it were an invested function. This tradition is shortsighted and ignores the reality that marketing expenditures don’t always produce returns in the fiscal year they’re made. Despite its relative importance, brand value is created and maintained, ad hoc, through budgets at most firms.

A second impediment to brand building efforts is a lack of board leadership. Marketing representation on corporate boards is pathetically low. The owners of what would be the largest asset on the balance sheet—the people with the most understanding of how value is generated and maintained—are seldom selected as stewards of that same value. Modern chief marketing officers are data literate, financially savvy, and lead most customer-facing communications and initiatives, yet they seem to be actively kept off corporate boards. Changing the accounting treatment of brand investment will take a top-down effort. So, putting more markers on boards will improve rate and likelihood of change.

Building an Interim Cosmic Ladder for Intangible Assets

Institutions like the Financial Accounting Standards Board (FASB), the International Organization for Standardization (ISO), and the Marketing Accountability Standards Board (the MASB) are formulating solutions to improve the measurement of intangible assets. Each body brings its own perspective, objectives, and cosmic ladder. Each must consider important questions about how new standards might affect corporate investment behavior, capital access, and tax liability.

The efforts of governance groups move slowly and we’re likely years away from mandatory changes to intangible asset accounting. In the meantime, there may some actions we can take to improve our understanding of corporate value by putting intangible value at the center of the equation.

The collection of investing metrics widely considered to be fundamental ratios includes price-to-earnings (P/E), price-to-sales (P/S), price-to-book (P/B), dividend yield, and return-on-equity (ROE). Investors tend to track the velocity of these metrics carefully.

The beauty of ratio statistics is that they’re comparable. That means ratios can be compared between companies and across time frames. So, what if we created a new set of intangible asset fundamentals to track how management generates value through intangible investment?

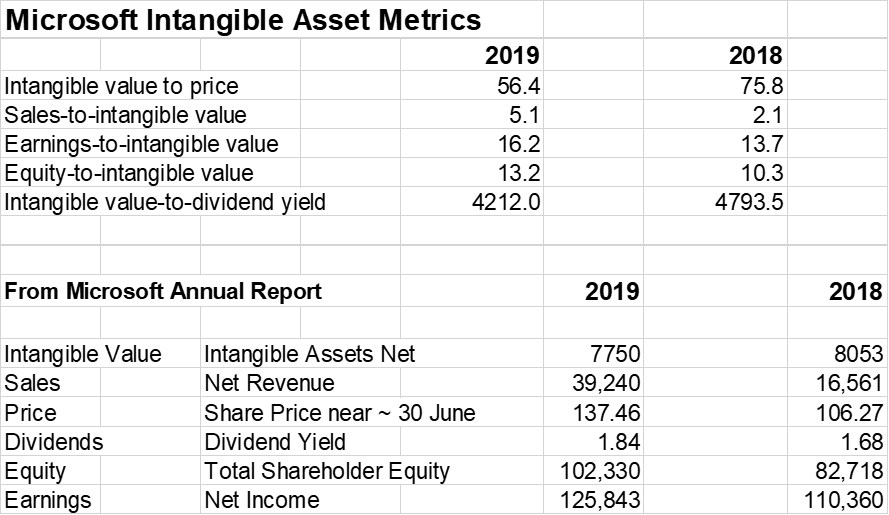

Below, are some alternative performance ratios built from publicly available information from Microsoft.

Amounts in millions

Like astronomers improving their understanding of the vast unknown, investors can use things they know to triangulate what they’re missing. “Laddering” of new and existing information could help gauge how management is improving intangible asset performance.

For example, it looks like Microsoft created much more value from its intangibles in 2019 than it did in 2018. Will these ratios address every issue related to management performance with intangibles? No, but it’s a good first step on the ladder.