Warren Buffett released the 2017 Berkshire Hathaway Letter to Shareholders on Saturday (read it here). Here are my 5 biggest takeaways from the letter:

Check out our H2 hedge fund letters here.

1. Impact of tax reform

Warren Buffett opens up the 2017 Berkshire Hathaway Letter to Shareholders by talking about the recent tax reform. Unfortunately he doesn’t go into much detail here, but he is very transparent with the fact that Berkshire Hathaway was a huge winner when Congress enacted the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act in December 2017. In 2017, Berkshire’s gain in net worth was $65 billion. $29 billion of that $65 billion gain in net worth, or 45%, was the direct result of the new tax code.

2. The 4 building blocks that add value to Berkshire Hathaway

Buffett explains that there are four building blocks that add value to Berkshire Hathaway:

1. Sizable stand-alone acquisitions

Warren Buffett and Charlie Munger look for companies with durable competitive strengths; able and high-grade management; good returns on the net tangible assets required to operate the business; opportunities for internal growth at attractive returns; and, finally, a sensible purchase price. (See : The 4 Warren Buffett Stock Investing Principles)

Nothing that Buffett reviewed in 2017 fit that last criteria. It seems that CEOs are in a frenzy to make deals and acquire other companies, pushing up prices. Why? “In part, it’s because the CEO job self-selects for “can-do” types. If Wall Street analysts or board managers urge that brand of CEO to consider possible acquisitions, it’s a bit like telling your ripening teenager to be sure to have a normal sex life.”

Berkshire had $115 billion in cash at the end of 2016, up from $86 billion at year end 2016. Buffett and Munger would prefer to use much of that cash to make some huge acquisitions, since currently it’s only earning next-to-nothing for them. “Our smiles will broaden when we have redeployed Berkshire’s excess funds into more productive assets.”

That said, Berkshire Hathaway did make one large acquisition last year: a 39% interest in Pilot Flying J. With $20 billion in annual revenue, Pilot Flying J is the dominant leader in truck stops and rest stops in the U.S. Berkshire is contractually obligated to increase its interest in the company to 80% in 2023.

2. Bolt-on acquisitions that fit with businesses Berskshire already owns

Berkshire made many smaller bolt-on acquisitions last year, as well as a few noteworthy larger ones:

- Clayton Homes – the manufacturer and financier of mobile homes and mobile home purchases – acquired two builders of conventional homes, doubling Berkshire’s presence in the conventional home builder market (a field the company entered only 3 years ago). Also worth noting, Clayton had a 49% market share of the mobile home market in 2016 – 3x larger than the next competitor and nearly 4x the 13% Clayton had in 2003 when Berkshire bought the company.

- Shaw Industries – the carpet and hardwood floors business – acquired U.S. Floors, a rapidly growing distributor of luxury vinyl tile.

- HomeServices – Berkshire Hathaway’s growing real estate brokerage operation – acquired the 3rd and 12th largest brokers in the country. HomeServices had originally been a very small part of MidAmerican Energy (now Berkshire Hathaway Energy) when Berkshire bought that company in 2000. Buffett had barely paid any attention to it. However, by 2016 HomeServices became the second-larges broker in the country; following the 2 acquisitions, it’s now close to being the largest. Still HomeServies only has a 3% total market share (which shows just how fragmented that real estate brokerage market is). As Buffett says, that “leaves 97% to go”.

- Precision Castparts bough Wilhelm Schulz GmbH, a German maker of corrosion resistant fittings, piping systems, and components. Buffett admits that he doesn’t understand manufacturing operations as well as he does real estate brokers, home builders, or truck stops. So he’s relying heavily on Mark Donegan, Precision’s CEO. However, “betting on people can sometimes be more certain than betting on physical assets.

3. Internal sales growth and margin improvement at Berkshire’s many and varied businesses

Berkshire Hathaway’s businesses can be broken down into insurance operations and non-insurance operations.

Insurance Operations

In this 2017 Berkshire Hathaway Letter to Shareholders, Warren Buffett once again talks about the importance of insurance float to Berkshire Hathaway and how it works:

“Insurance float has been of great importance to Berkshire. When we invest these funds, all dividends, interest and gains from their deployment belong to Berkshire. (If we experience investment losses, those, of course, are on our tab as well.)

Float materializes at p/c insurers in several ways:

- Premiums are generally paid to the company upfront whereas losses occur over the life of the policy, usually a six-month or one-year period;

- Though some losses, such as car repairs, are quickly paid, others – such as the harm caused by exposure to asbestos – may take many years to surface and even longer to evaluate and settle;

- Loss payments are sometimes spread over decades in cases, say, of a person employed by one of our workers’ compensation policyholders being permanently injured and thereafter requiring expensive lifetime care….

Float will probably increase slowly for at least a few years. When we eventually experience a decline, it will be modest – at most 3% or so in any single year. Unlike bank deposits or life insurance policies containing surrender options, p/c float can’t be withdrawn. This means that p/c companies can’t experience massive “runs” in times of widespread financial stress, a characteristic of prime importance to Berkshire that we factor into our investment decisions.”

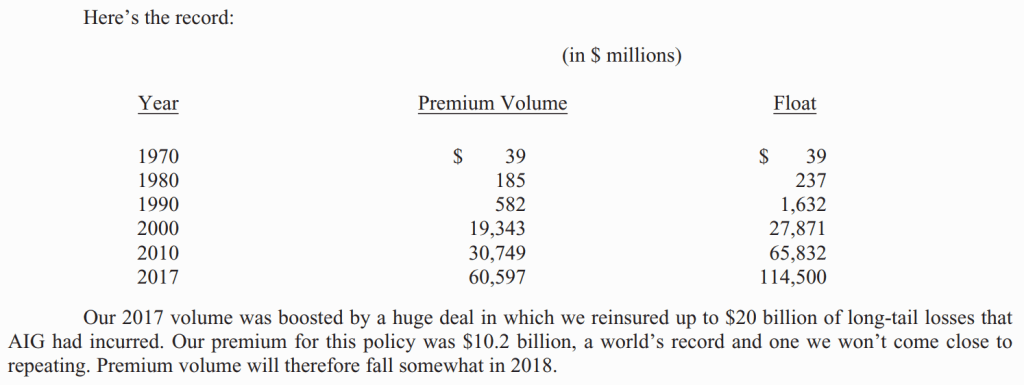

Let’s take a look at Berkshire’s float record:

The downside with float is that it comes with risk – sometimes A LOT of it. Buffett concludes:

“Charlie and I never will operate Berkshire in a manner that depends on the kindness of strangers – or even that of friends who may be facing liquidity problems of their own. During the 2008-2009 crisis, we liked having Treasury Bills – loads of Treasury Bills – that protected us from having to rely on funding sources such as bank lines or commercial paper. We have intentionally constructed Berkshire in a manner that will allow it to comfortably withstand economic discontinuities, including such extremes as extended market closures.”

Following last year’s major hurricanes in Texas, Florida, and Puerto Rico, Berkshire’s net worth fell by less than 1% – many other companies in the reinsurance industry suffered losses in net worth ranging from 7% to more than 15%.

Berkshire would barely feel the pain from even a mega-catastrophe event – one that causes $400 billion or more of insured losses (total, not just to Berkshire; by comparison, last year’s hurricanes probably caused about $100 billion). A mega-cat of this magnitude would likely put much – if not most – of the p/c insurance world out of business.

Berkshire’s insurance businesses generated after-tax losses from underwriting of $2.2 billion in 2017, compared to an after-tax gain of $1.4 billion in 2016.

Non-Insurance Operations

Berkshire’s non-insurance companies generated $20 billion of pre-tax income in 2017, an increase of $950 million over 2016. Nearly half of the profit came from just two of Berkshire’s businesses: BNSF (the railroad) and Berkshire Hathaway Energy. Buffett doesn’t spend much time discussing Berkshire’s non-insurance operations as more detailed information can be found in Berkshire Hathaway’s 10-K report for 2017.

4. Investment earnings from Berkshire’s huge portfolio of stocks and bonds

Below is a table summarizing Berkshire Hathaway’s largest stock holdings at year end:

Some very important things to note:

- Apple is Berkshire Hathaway’s second largest stock holding, and it’s only just behind #1 Wells Fargo.

- Kraft Heinz is Berkshire’s second largest stock holding at $25 billion of market value (not included in the chart above because of accounting rules that require Berkshire to record its ownership under a different method).

- Todd Combs and Ted Weschler each manage more than $12 billion. Both make decisions independent of Buffett. Still, together they represent less than 15% of Berkshire’s total portfolio.

3. “In the short run, the market is a voting machine; in the long run, however, it becomes a weighing machine.”

Warren Buffett repeats Ben Graham’s famous quote: “In the short run, the market is a voting machine; in the long run, however, it becomes a weighing machine.” (Read: The Intelligent Investor)

In other words, in the short-run stock prices are like a popularity contest – stocks go up or down not based on their true intrinsic value but on other external factors; in the long-run, however, stock prices tend to be based on actual worth. This means that volatility in prices in the short term and obscure long-term growth in value. Buffett continues:

“Berkshire, itself, provides some vivid examples of how price randomness in the short-term can obscure long-term growth in value. For the last 53 years, the company has built value by reinvesting its earnings and letting compound interest work its magic. Year by year, we have moved forward. Yet Berkshire shares have suffered four truly major dips. Here are the gory details:”

Yet despite these 4 major periods of decline, Berkshire Hathaway’s stock price has still compounded at a rate of over 20% per annum over the past 50+ years! Back to Buffett:

“This table offers the strongest argument I can muster against ever using borrowed money to own stocks. There is simply no telling how far stocks can fall in a short period. Even if your borrowings are small and your positions aren’t immediately threatened by the plunging market, your mind may well become rattled by scary headlines and breathless commentary. And an unsettled mind will not make good decisions.”

Buffet warns that in the next 53 years, Berkshire’s shares (and the rest of the stock market) will very probably experience declines resembling those in the table above. And no one will be able to tell you when these declines will happen. “The light can at any time go from green to red without pausing at yellow.” But when these major declines do occur, they offer “extraordinary opportunities to those who are not handicapped by debt.”

4. “The Bet” is officially over… guess who won?

“The Bet” was a $1 million bet that Warren Buffett made with a hedge fund called Protégé Partners. Buffett bet that a virtually cost-free investment in an unmanaged S&P 500 index fund would, over the course of 10 years, deliver better results than those achieved by most investment professionals, however well-regarded and incentivized these hedge funds may be.

Well, here are the results:

Despite a fast start in 2008, in which every fund-of-funds beat the S&P Index Fund, performance was pretty abysmal thereafter. In every single one of the nine years that followed, the fund-of-funds as a whole trailed the index fund. Not one individual fund even came close to matching the 8.5% average annual gain for the S&P Index Fund over the 10 years. One fund was even liquidated in 2017 because its performance was so bad! As Buffett says: “Performance comes, performance goes. Fees never falter.”

5. Bonds are for the birds. The S&P 500 may be the world’s safest long-term investment.

The bet illuminated some other important investment lessons. But first we need to understand the mechanics of how the bet was actually made:

To fund the $1 million 10-year bet (which was to be donated to charity), Buffett and Protégé each bought $500,000 face amount of zero-coupon U.S. Treasury bonds. They each paid $318,250 for these bonds, which would pay the $500,000 face value to them in 10 years (with no interest). The rate of return if held to maturity would be 4.56%.

However, by late 2012 the bonds – now with still 5 years to go before they matured – were selling for 95.7% of their face value (i.e. $478,500 each). An investor who bought this bond would receive an annual rate of return of less than 1% (remember, they still would only get the $500,000 face value when the bond finally matured)! Given that pathetic return, Buffett and Protégé recognized that holding onto their bonds would be a very dumb investment decision compared to American equities (the cash return from dividends alone on the S&P 500 was 2.5% – about triple the yield on those U.S. Treasure bonds).

So, Buffett and Protégé sold their bonds in 2012 and used the proceeds to buy 11,200 Berkshire Hathaway “B” shares. The result: Buffett and Protégé were able to donated a total of $2,222,279 to charity in early 2018 versus the $1 million they had originally planned for.

This little story helps explain two very important investing lessons:

1. Over the long-term, a diversified basket of equities are a much better investment than a bond. As Buffett explains:

“Investing is an activity in which consumption today is foregone in an attempt to allow greater consumption at a later date. “Risk” is the possibility that this objective won’t be attained.

By that standard, purportedly “risk-free” long-term bonds in 2012 were a far riskier investment than a long-term investment in common stocks. At that time, even a 1% annual rate of inflation between 2012 and 2017 would have decreased the purchasing-power of the government bond that Protégé and I sold.”

Of course, in any upcoming day, week, or even year, stocks will be far riskier than bonds – we saw that in the chart above that showed the 4 major declines in Bekrshire Hathaway’s stock price. But over the very long-term, it’s very nearly certain that the S&P 500 will grow about 6-9% per annum.

“It is a terrible mistake for investors with long-term horizons – among them, pension funds, college endowments and savings-minded individuals – to measure their investment “risk” by their portfolio’s ratio of bonds to stocks. Often, high-grade bonds in an investment portfolio increase its risk.”

2. Secondly, an investment decision is made everyday – and not just when you buy or sell an asset. In the above example, had Buffett and Protégé held on to the U.S. Treasury bonds, they still would have been paid the $500,000 face value amount after year 10 and the rate of return still would have been 4.56%.

But in late 2012, when the bonds were selling for 95.7% of their face value, they faced a binary decision – either:

- Option A: Hold on to the bonds and earn the 4.56% return over the 10 year period, or

- Option B: Sell the bonds, receive $478,500, and then re-invest those proceeds in another asset.

In Option B, the new investment Buffett and Protégé had to make with the sales proceeds only had to beat a 0.88% return; that is, the investment only had to increase the value of the $478,500 in 2012 to $500,000 by 2017 (which would equate to a 0.88% return).

If you were to choose Option A, you might have thought that it was a wise decision – a 4.6% return over 10 years in a “risk-free” asset is pretty good, after all. But when you look at Option B, it’s apparent that choosing Option A would have been a very bone-headed decision.

More on Warren Buffett’s Berkshire Hathaway Letters to Shareholders

- The Essays of Warren Buffett: Lessons for Corporate America

- University of Berkshire Hathaway: 30 Years of Lessons Learned from Warren Buffett & Charlie Munger at the Annual Shareholders Meeting

- Buffett’s Annual Letter – 2017

- 2017 Berkshire Hathaway Shareholders Meeting (Full Transcription)

- The 25 Greatest Quotes from Warren Buffett’;s 2016 Berkshire Hathaway Shareholder Letter

- My Top 3 Takeaways from the 2016 Berkshire Hathaway Annual Shareholders Meeting

- 4 Myths Warren Buffett Busted in the 2015 Berkshire Hathaway Shareholders Letter

- Free Berkshire Hathaway Annual Shareholder Meeting 2015 E-Book

- Best of 2015 Berkshire Shareholder Meeting

- The Berkshire Hathaway 2014 Annual Report

- Consolidated and Condensed Letters to Berkshire Hathaway Shareholders, 1977-2016

- The Complete List of Q4 2017 Hedge Fund Letters to Investors

Article by Vintage Value Investing