Absolute Return Partners January 2018 letter titled, “My Not So Outrageous Predictions.”

It is not bad economics that will send this market lower. It’s good economics.

We are now only a couple of months away from the publication of my first book – The End of Indexing (see below). With passive investing growing by the day, how on earth have I come to the conclusion that the end is nigh as far as indexing is concerned? At this early stage I just want to whet your appetite. More on the subject next month.

Saxo Bank’s outrageous predictions

In the meantime, let’s switch to something that is far more relevant to the January Absolute Return Letter. As you may recall, the January letter is always about risks that we should worry about in the year to come. Readers often ask me: “Why are you always so negative?”. I am really not, but the Absolute Return Letter is about risk management; hence the negative bias. Have you ever heard about risk managers focusing on the opportunity set? Just asking.

Talking about things we should worry about, Saxo Bank has made a habit of publishing its so-called Outrageous Predictions every January, and they didn’t disappoint us this year either. Yet again, Saxo came up with a basket of predictions that were thought-provoking and entertaining at the same time. Don’t assume I agree with all of them, just because I list them, but here they are:

- Fed loses independence as US Treasury takes charge.

- Bank of Japan loses control of its monetary policy.

- China issues CNY-denominated oil futures contract.

- Volatility spikes on sudden S&P 500 ‘flash crash’.

- US voters push left in 2018 mid-terms, bonds spike.

- ‘Austro-Hungarians’ launch hostile EU takeover.

- Investors flee Bitcoin as governments strike back.

- South Africa resurgent after ‘African Spring’.

- Tencent topples Apple as market cap king.

- Women take the reins of corporate power.

Which ones do I agree with? First and foremost, you have to remind yourself they are called outrageous for a reason, but that doesn’t imply they are all so far-fetched, it’s almost laughable. In the world I see in front of me, the most likely to unfold in the year ahead are numbers 3, 4, 7 and 8.

As far as #3 (CNY-denominated oil futures) is concerned, knowing China’s desire for a place at the main table, it is not at all unthinkable that they would introduce a CNY-denominated oil futures contract. Having said that, I don’t know enough about China’s role in international oil markets to quantify the risks and opportunities implied by that.

As far as #4 (volatility) is concerned, whether volatility will spike as a consequence of a sudden flash crash or because of something entirely different is hard to say, but we have lived in la-la land for too long. Something will happen in the not so distant future that will cause volatility to spike, but more about that below.

As far as #7 (Bitcoin) is concerned, why do I think the party could be (nearly) over? As you may or may not be aware, Bitcoin has turned into an Eldorado for drug dealers, tax evaders and other dodgy individuals who need to launder their dirty money, and governments all over the world are keen to put a stop to that practice. For what it is worth, I think Bitcoin will top out at levels substantially higher than today’s, but top out it will, and the downfall will be dramatic.

Finally, as far as #8 (South Africa) is concerned, the driver behind my reasoning is the recent election of Cyril Ramaphosa as leader of ANC, which makes him the most likely next president of South Africa. He is a very successful businessman, and the election of him is probably the most positive thing that has happened in South Africa for years.

My biggest concerns going into 2018

Now to the most likely hiccups in 2018, as I see things. Is 2018 going to deliver anything truly cataclysmic? I don’t think so, which is why North Korea hasn’t even made it to my list of the most likely setbacks in the year to come. Having said that, would I put $1 million on no military conflict between the US and North Korea in the year to come? No!

Anyway, my top five predictions are (in no particular order):

- Turbulent Brexit negotiations taking the UK to the cliff edge.

- General elections in Italy turning the country anti-EU.

- Mayhem in Saudi Arabia leading to a dramatic rise in oil prices.

- Synchronised GDP growth leading to rising wage inflation.

- The US equity market turning into Japan of the late 1980s.

1. Brexit negotiations taking the UK to the cliff edge

Let’s begin with the hottest topic of them all – at least here in the UK – and that is Brexit. If lacking a bit of atmosphere, all you need to do is to join a dinner party attended by Brits, and I can guarantee a most lively evening. In the UK, national pride increasingly rules over economic logic. “18,000 jobs will be lost in Germany, if we don’t buy their cars anymore”, the media scream whilst encouraging UK negotiators to simply walk away from the divorce negotiations, such is the anger. To make matters worse, the man in the street takes it all at face value, which has created an atmosphere of extreme anti-EU sentiment that now borders on outright hostility.

I am not going to argue against the suggestion that 18,000 German jobs could be lost, because that could very well be correct, but what about the hundreds of thousands of jobs that will almost certainly be lost in the UK? Let me share a few numbers with you. (Note: Source: Office for National Statistics.)

About 3 million people work in the UK manufacturing industry and a further 1.2 million in financial services. Those two sectors will probably be the most severely impacted, should we end up with no deal, although one shouldn’t ignore the negative impact such an outcome would have on the construction industry, which employs 2.4 million people.

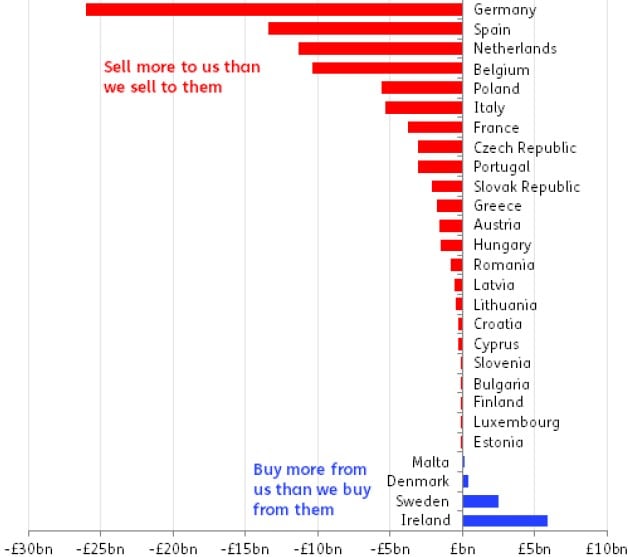

The fact that the UK is a net importer of goods from the rest of the EU is frequently used by the anti-EU brigade to make the point that no trade agreement would be far worse for the rest of the EU than it would for the UK. “We buy much more from them than they buy from us, so they need us more than we need them”, is the prevalent argument. (Note: Nigel Farrage (the ex-leader of UKIP) now runs a radio show in London, and he brings up this argument almost daily. I find it quite amazing that the penny hasn’t dropped yet.)

Whilst absolutely correct that the UK is a net importer from almost all EU countries (exhibit 1), that fact is entirely irrelevant as far as job security is concerned. What matters there is the extent of the damage to the industry in question that no agreement would inflict, and on that account the UK stands to suffer a great deal more than the EU.

In 2017, a modest 6% of total EU exports went to the UK, whereas a massive 48% of UK exports went to other EU countries (Note: Source: Eurostat. Numbers updated through September.). Where do you think most jobs will be lost (as a % of the workforce) if there is no trade agreement going forward? I certainly know, and so do many others, but nobody dares to mention it for the fear of being deemed unpatriotic.

In early December, when everybody thought a deal between the UK and the EU had finally been struck, everything suddenly fell apart, because Theresa May had ‘forgotten’ to secure the support of DUP – the Ulster party that she is dependent on for her majority in parliament. My prediction for 2018 is that we will have more of these cliff-edge moments before everything is done and dusted. A choppy sterling is therefore in the cards.

As the Brexit negotiations progress, should the government fall (and that could easily happen given its razor-thin majority in parliament), I would assign a 60-70% probability to the next tenant of 10 Downing Street carrying the name Jeremy Corbyn. I wouldn’t want to own a single UK share if that were to happen.

2. General elections in Italy turning the country anti-EU

As far as Italy is concerned, it is hardly a secret that the man in the street is not particularly pro-EU at present. It is actually impossible to find another EU member country where the public opinion is more negative than it is in Italy. Nowadays, even the Greeks rate the EU more favourably than the Italians do (exhibit 2).

Source: World Economic Forum

The political picture in Italy is rather messy (which is sort of a tradition there, I suppose), here less than two months before election day. A centre-left coalition between PD, AP and MDP is the most likely outcome, but the centre-right parties (FI, LN and Fdl) are not far behind in the opinion polls (exhibit 3).

Source: BMI Research, The Daily Shot

Even a coalition between the anti-establishment party M5S (Movimento 5 Stelle) and LN (Lega Nord) is a possibility, and that would really let the cat in among the pigeons. Membership of the Eurozone would almost certainly be on the agenda, and even a referendum on continued EU membership could not be ruled out. If that were to happen, the entire EU foundation would shake and financial markets would puke a great deal more than they ever did during the turmoil in Greece.

Many commentators I read assign a near 0% probability to that happening though, but I note that real earnings have fallen in Italy in recent years, just like they have in the UK and the US. And, as we learned in those two countries, when living standards are under pressure, voters want things to change, even if they don’t always fully understand exactly what it is that must change. Falling living standards gave us Trump in the US and Brexit in the UK. What will they bring in Italy?

3. Mayhem in Saudi Arabia

When Mohammed bin Salman took control of Saudi Arabia, the reaction across the world was overwhelmingly positive. Finally a Saudi leader who could take the Kingdom into the 21st century, we all thought. And, to be fair to bin Salman, much of what he has achieved until now has been good for the country. He has for example imprisoned a number of deeply corrupt people, who deserved no better.

However, the story doesn’t stop there. When you have the power to do such things, as we have seen before, you don’t always restrict yourself to the bad guys. Quite often, political enemies also become a target. More than 60 prominent clerics, writers, academics, religious figures, journalists and activists have been detained in Saudi since the clampdown began last September, leading to significant unrest around the country. (Note: Source: The Guardian)

On an altogether different front, a war between Saudi Arabia and Iran no longer looks as unlikely as it did only a few short months ago, and that would indeed be a war between two Middle Eastern superpowers. Much of the conflict has to do with Yemen and, as I write these lines, I read on the internet that Yemeni rebels have just fired another ballistic missile at a Saudi military camp. The Saudis continue to accuse Iran of supporting the Houthi rebels in Yemen.

One may ask the valid question: What is it all about? I do not proclaim to be an expert on Middle Eastern affairs, but my understanding is that it is an absurd mix of religion and geopolitics that is at stake here. The two countries are both oil-rich; they are located on either side of the Persian Gulf (exhibit 4) and both aim for supremacy in the region. At the same time, one (Saudi Arabia) is the Sunni powerhouse in the Middle East, whereas the other one (Iran) is the main hub for Shiites.

Source: The Guardian

How it will all end is difficult to say, but I am inclined to think that fighting ‘wars’ on several fronts, as Mohammed bin Salman does at present, is a flawed tactic. There are very few examples of people coming out on top, when they fight more than one battle at the time.

Mayhem is therefore an outcome that I would assign a relatively high probability to and, with mayhem in Saudi, higher oil prices will almost certainly follow. I have seen one commentator (CNBC) suggesting $200 per barrel of oil, but it is extremely difficult to say. I will say one thing, though. If the conflict between Saudi and Iran results in open warfare between the two countries, it could take not one but two major oil producers out for a while, and a $200 oil price no longer looks unlikely.

You can read more about the conflict between Saudi Arabia and Iran here.

4. Synchronised GDP growth leading to rising wage inflation

Before you read any further, let me make one thing crystal clear. The risk of rising inflation and higher interest rates is short-term in nature. Five years from now, I think interest rates will be lower than they are today. Having said that, I cover that topic in great detail in my new book and shall save you from all the details now.

With that in mind, I think inflation could rise meaningfully this year and, if that were to happen, so will interest rates most likely. It is a fact that, for the first time since the financial crisis erupted in 2007-08, economic growth is synchronized with virtually all countries growing robustly now (exhibit 5), and it is also a fact that, when economic growth is largely synchronized, wage pressures almost always rise and lead to an increase in inflation.

Source: Oxford Economics

There are obviously some very good reasons why I think interest rates will start to decline again longer term, and at least some of those reasons are also why some observers don’t think rising interest rates are a risk one should be overly concerned about going into 2018.

Allow me to (very) briefly mention a few of those structural reasons that are holding back inflation as well as interest rates. The prime suspect is probably low productivity growth. In a report from last year, IMF concluded that weak productivity growth is the main reason why wage growth is so pedestrian at present. Even in countries where unemployment levels are now below 2000-2007 averages, wage growth is very modest (see here).

Another factor is public sector austerity. I don’t know the details of every country around the world but, at least here in the UK, public sector workers have not seen significant pay rises for some years now. Yet another factor is automation. The fear of losing their job to robots has most definitely caused many workers (and their unions) to moderate demands. And I could go on but, in the interest of time, I will stop here.

Of the five potential 2018 hiccups that I discuss this month, it is admittedly the one I am least convinced about, which probably means it is the only one that will actually happen, such is Murphy’s Law. The fact that the structural trends that hold back inflation are very powerful, is the reason behind my lack of conviction.

5. The US equity market turning into Japan of the late 1980s

Now to the final one of my five concerns. Japan of the late 1980s - what do I mean by that? As I am only too aware that not all my readers are as old as I am, allow me to summarise what happened in Japan in the late 1980s.

Back then Japan delivered the mother of all bull markets. Equity prices kept going up and so did property prices with investors paying little attention to economic logic. At the peak, the land surrounding the Imperial Palace in Tokyo was said to be worth more than all of California! The Japanese even have a name for that extraordinary bubble: バブル景気.

The bubble was not only characterised by inflated asset prices, but also by largely uncontrolled money supply, by excessive credit expansion and by disproportionate monetary easing. Does that ring a bell? By the early 1990s, it was all over, and the decade of the 90s turned into what is now known as the Lost Decade.

What I don’t like about US equities right now is that they defy logic, just like Japanese equities defied logic back in the late 1980s. US valuations are not only out of whack with those of other equity markets around the world but also relative to past valuation levels (exhibit 6).

Source: Moody’s Investor Service, The Daily Shot

Furthermore, as a result of inflated equity prices and strong property markets, US wealth is accumulating at a faster pace than anywhere else (exhibit 7). The best way to measure how much asset price inflation has affected wealth in the US is to zoom in on the wealth-to-GDP ratio, which is long-term constant (Note: I don’t intend to go into any level of details here as to why that is, but it is a major topic in my forthcoming book.). The US mean value is 3.8, and I note that wealth is now in excess of 5 times GDP in the US; i.e. total wealth will have to drop 25-30% for equilibrium to be re-established.

Source: Credit Suisse Global Wealth Data Book 2017, The Daily Shot

In other words, it is only a question of time before risk assets take a significant hit in the US, and I am prepared to stick my neck out and suggest that 2018 could be the year when the adjustment phase begins.

Having said that, one thing I also learned from the Japanese experience is that, when bubbles rage, asset prices can defy logic a lot longer than what you think is possible. There is absolutely no reason why the bubble cannot get even bigger before it eventually blows up, but blow up it will.

What a time to be alive

Allow me to finish the 2018 Hiccup Letter by repeating what I said to begin with. I am not at all the doom and gloom person some of you may think I am. Having said that, I am paid to focus on risk, and I learned during the crisis in 2007-09 that whilst the upside takes care of itself, only the best investors manage the downside risk well.

One of the reads I have enjoyed the most more recently is this one. As you can see, I can also get a kick out of more positive things. I hope 2018 brings success and happiness to all of us. What a time to be alive!

Article by Niels Clemen Jensen, Absolute Return Partners