ESG investors want to advance decarbonization, but are their ESG strategies achieving these aims? It’s a question we delve into in our research, and on several syndicated podcasts.

Q4 2020 hedge fund letters, conferences and more

Massiff Capital's View On ESG Strategies

Those familiar with our blog, know our view: ESG strategies, which typically utilize exclusionary screens in the investment process, simply invest in companies with a current low carbon footprint. In our view, that does not advance decarbonization because it does nothing to force or encourage change among companies that are large carbon emitters, but are nevertheless essential to the modern economy.

But ESG strategies can’t fix the problem alone. Management teams at real asset companies who have a long-range vision for decarbonizing their carbon heavy business could do more to articulate their vision.

In a recent podcast with Decarb Connect, we explained our position on ESG strategies, and alternatives investors should consider if their goal is to create a carbon-neutral economy. We also offered five questions boards should ask management teams of these business, so that investors can better understand the companies’ goals and initiatives toward decarbonization:

- What are the material environmental risks that your business faces, and how well are you managing them?

- Have you set compelling sustainability targets and goals related specifically to those material environmental risks?

- Can you integrate those goals and risks into your financial reporting, and if so, what is the impact?

- What accountability have you set for environmental-related performance?

- How are you communicating this to the market, to shareholders and to rating agencies?

Failure To Impact: Are Esg Funds Delivering On Investors’ Ambitions?

Introduction

The momentum behind ESG investing has grown enormously in recent years. Despite the growth, the ESG investment universe remains challenging to have a productive conversation about as environmental, social, and governance concerns are diverse enough to allow for almost any issue to be subsumed by the acronym. Furthermore, like so many in financial marketing terms, ESG lacks any descriptive quality that enables an investor to understand how a strategy is built around the individual variables. Despite the numerous shortcomings that arise from such a poorly constructed acronym, environmental, social, and governance variables are critical in evaluating a business’s value. The materiality of environmental, social, and governance issues to a company is contextual though, and difficult, if not impossible, to evaluate in the often rote quantitatively driven way so common to a diverse set of investment strategies currently being marketed to investors under the ESG moniker.

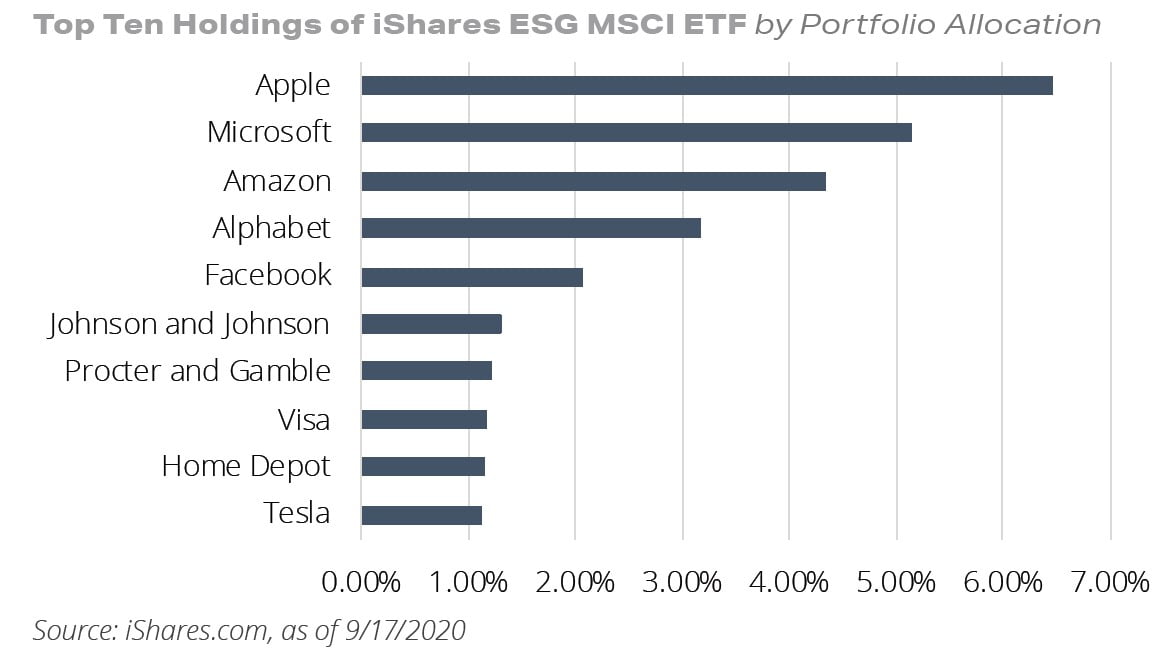

Environmental issues, in particular, are highly contextual. That some firms pollute more than others is a mostly meaningless observation. Yet, the unsophisticated ranking of firms based on environmental footprint is just that, an observation that some firms pollute more than others. Without an analysis of a business’s economic significance or criticality to the broader economy, its environmental impact is without an essential interpretive context. That firms such as Apple and Microsoft, two of the most widely held businesses in ESG portfolios, pollute less than copper miners and aluminum producers is a meaningless observation in the context of a desire to invest for impact. That firms like Apple and Microsoft depend on copper miners and aluminum producers for their businesses means that the question investors should be asking is how one balances environmental impact and economic criticality, not simply how one limits a portfolio’s overall environmental impact.

According to The Forum for Sustainable and Responsible Investors, climate change is the number one issue for asset managers with ESG mandates. A 2019 Morgan Stanley report, detailing the interests of ESG investors in the United States with more than $100,000 in investable assets, further identified climate change and the environment as the principal motivation behind ESG allocations. The survey also found that 71% of investors believed their investments could influence the amount of climate change caused by human activities and that the desire for their investments to have an impact was the core motivation for allocating capital to ESG investment products.

When considered alongside the spread of divestment actions by institutional investors, and numerous other qualitative items, such as the Larry Fink’s most recent Letter to CEOs, it is reasonable to conclude that the environment, and specifically slowing climate change, are two key motivations driving ESG investment products.

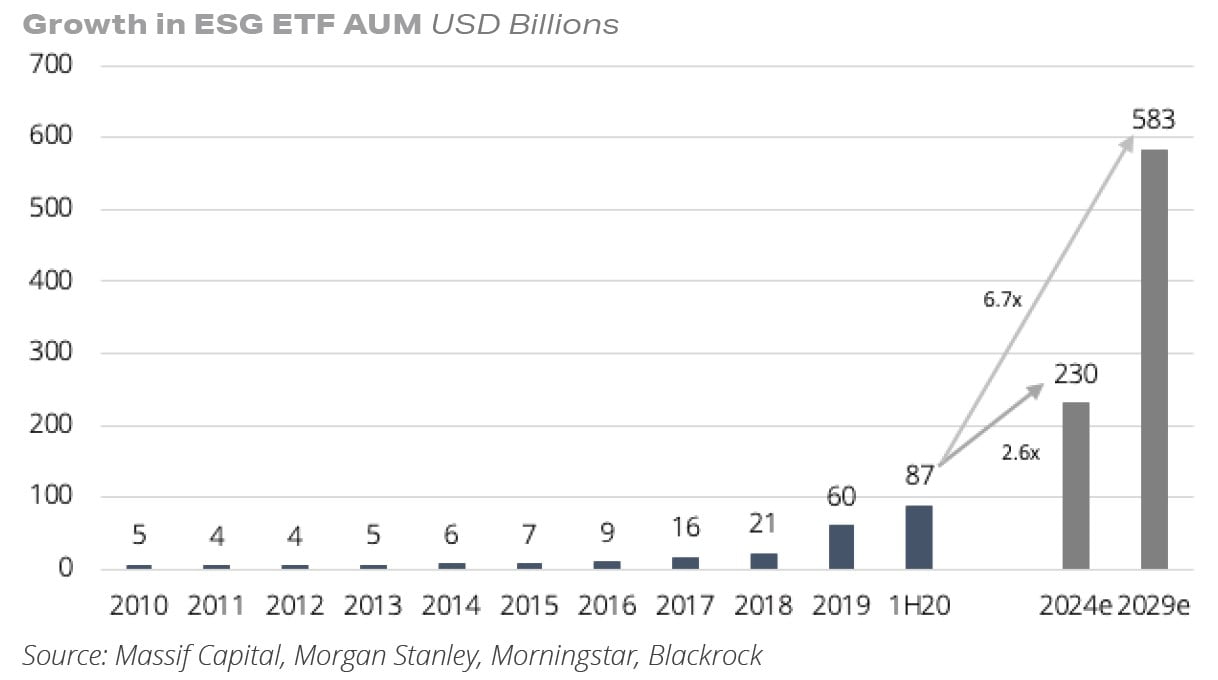

That most products marketed to such investors rank environmental impact without consideration given to context should thus be a cause for concern. That investors are increasingly allocating their ESG dollars to ESG ETFs, which as a result of their construction process do nothing more than arbitratily rank companies, should be of even more concern. The primary motivation for writing this paper is to highlight that the trend toward passive ESG vehicles is likely only to exacerbate the environmental analysis that produces results directly counter to the stated objectives and intent of most investors.

One can think of environmentally concerned portfolios as falling into one of two categories.1 One category are portfolios constructed to reduce climate-related risk by allocating capital to investments in businesses that rank highly in any of the ESG rankings available to investors.2 This approach would include the divestment of steel companies or avoiding business with controversial environmental histories (for example, the bursting of a tailings dam at a mine).3 The vast majority of passive ESG vehicles take this approach.

The alternative is to consider climate change as a problem that can be addressed and invest in companies that will aid or benefit from the transition to a low carbon economy. Of these two approaches, the simplicity and ease with which the first can be executed in an ETF structure has led to its widespread adoption.4 Given that ESG ETFs primarily allocate capital to companies that do no harm to the environment but also do not do any good either, such investments are at odds with the stated desire of 71% of ESG investors to have a positive environmental impact.

Investors can thus rightly ask: If my ESG ETF investment produces no positive impact, does it, by dint of directing capital away from firms critical to transitioning the economy to a more sustainable footprint, do more harm than good. Aligning a portfolio with one’s values by investing in companies that are not objectionable is fine, if that is your goal. It is, however, very different from investing in companies that will not only survive in an economy transitioning to a low-carbon footprint, but that also enable that transition. We fear that over time, as ESG ETFs proliferate, a significant opportunity to promote change via smarter capital allocation will be lost in the widespread misallocation of investor capital.

To hear more of the podcast, listen here. Or read our position paper, Failure to Impact: Are ESG Funds Delivering on Investors’ Ambitions?