Based on the dot.com experience, popping bubbles are often associated with the complete collapse of companies like eToys, Pets.com or Webvan, but that is as much the exception as the rule. It is equally common that following an immense and unsustainable rise in stock price, the bubble pops without much change in the operations and profitability of the company. Instead, the bubble is based on the development of a wildly enthusiastic prediction of the company’s future and is popped by the recognition that the forecasts were wildly enthusiastic. All of this can happen without much change in ongoing operations. The best way to illustrate what can happen is with some examples.

Q3 2020 hedge fund letters, conferences and more

Popping Bubbles: Let's Start With GoPro

A good place to start is with GoPro. GoPro is a maker of action cameras popular with athletes and outdoor activity enthusiasts. As with many tech companies, GoPro went public in mid-2014 with all the associated excitement. In a story that was to become increasingly common, GoPro was billed as much more than a camera company in a competitive photography market. It was a budding social media company for the active set. It was a potential competitor for YouTube. It was a “lifestyle” company. It was going to reinvent the drone. In response to the hype regarding the bevvy of opportunities, the market price of GoPro skyrocketed reaching a high of nearly $100, giving it a market cap of over $11 billion.

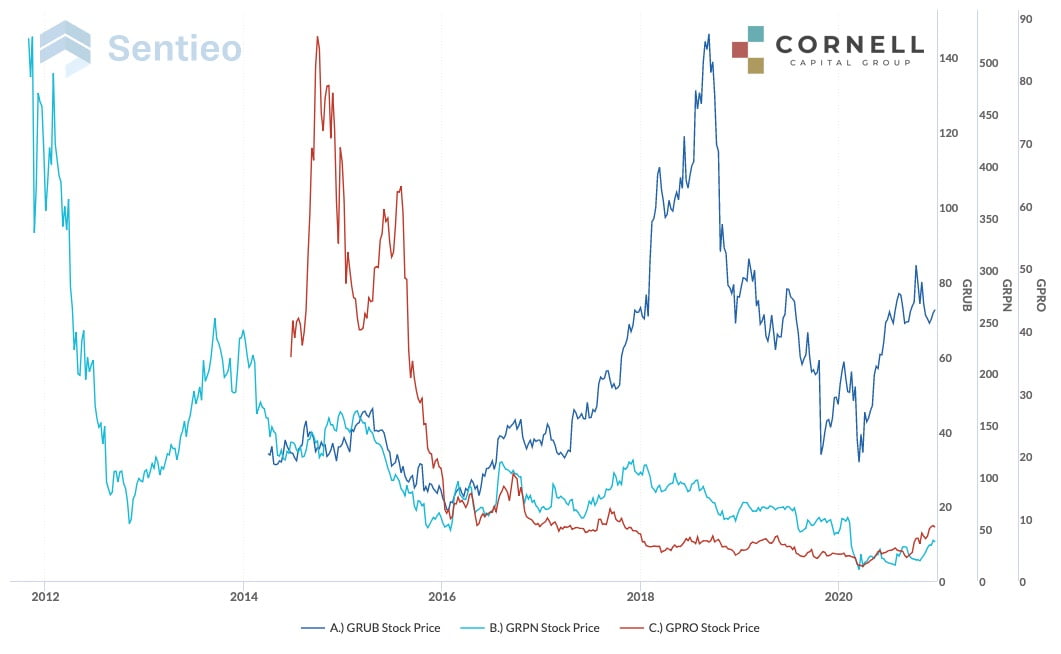

Unfortunately, reality set in. It turned out that GoPro was a camera company. True it was an innovative camera company, but it was not a social media firm or the new YouTube. As a result, the stock price plummeted. As shown in the graph below, by year end 2017, the company was trading for less than $10 per share, a level it has yet to surpass since then. This does not mean that GoPro was a failed company. It still makes a good action camera in a competitive market. It trades at what now appears to be close to fair value. The bubble popped back in 2015 when the expectations were found to be wildly optimistic, but the company never failed.

Grubhub

Another example is Grubhub, the DoorDash of 2012. Like GoPro, Grubhub went public to great fanfare but the run-up was delayed. It was not until years after the company went public that its stock ran up to $150 per share as expectations became increasingly bullish. Today Grubhub is still around and still delivering food, but as shown on the graph below the stock price has dropped to $72 and that is with the benefit of Covid. Before the Covid rebound, the stock price had fallen to $31.70. The company never met the forecasts promulgated during its halcyon days. Those expectations, or hopes, have been transferred to DoorDash. For instance, the current market cap of DoorDash is $50.4 billion compared to Grubhub at $6.7 billion.

GroupOn

GroupOn provides a final example. The company was going to change the way consumers transact by developing an online marketplace that sells coupons for local retail and service providers. Small businesses using GroupOn can market themselves by selling products at discount in the hope that new customers from GroupOn will pay regular price after the deal has expired. The belief that GroupOn’s technology would be a major hit pushed the stock price up over $500 per share in 2019. Since then, the company has continued to perform as it did in the year during the run up, and that is the problem. Reliable performance does not justify sky high stock prices. It does not signal the next Amazon. As a result, the graph shows that Groupon’s stock price fell below $10 in March of this year. Ironically, it is up nearly 400% from its pandemic low. Expectations can change in either direction.

The pattern described by the examples is not unique to small or new companies. If you think back to the dot.com bubble, stock prices of highly successful companies like Microsoft and Intel also collapsed while their businesses continued to prosper. An investor who bought Microsoft at the height of the dot.com bubble had to wait fifteen years before the stock price returned to that level. Throughout those fifteen years Microsoft’s earnings continued to grow.

Today there are many companies that could echo the experience of GoPro, Grubhub and Groupon. Among the more famous candidates are Chewy, Peloton, Tesla, DoorDash, and Airbnb, but there are many others. All these are good companies with potentially bright futures. The problem is that in every case the story necessary to justify the current stock price is reminiscent of the irrational exuberance that launched GoPro, Grubhub and Groupon into the stratosphere. If the stories prove to be unrealistic, those companies could have a GoPro like experience. But to repeat, that does not mean that they will fail. The simple fact is that bubbles can expand and pop with remarkably little change in the underlying performance of the company. If the expectations of world changing performance evaporate, a company’s stock price can crater even as its earnings continue to grow.