My father, Bob Bauman, has traditionally published a holiday-themed Sovereign Investor Daily article on special occasions like Christmas, Thanksgiving and the Fourth of July.

He’s a fount of knowledge about American traditions. He deftly weaves in tasteful commentary about current events.

He’s done a few on Labor Day, too. But this year it falls to my regular Monday column. So, continuing the family tradition, here goes nothing.

The official story is that “Labor Day is a public holiday, celebrated on the first Monday in September, honoring the American labor movement and the contributions that workers have made to the strength, prosperity, laws and well-being of the United States.”

The truth is darker … but it provides a ray of hope in troubled times.

The First Gilded Age

The U.S. economy transformed itself after the Civil War. An agrarian nation with a little manufacturing in the Northeast became an industrial powerhouse.

Millions of Americans left their farms to work in factories and mines, and on the railways that connected them. For the first time, the U.S. had a true industrial working class.

Like today, to which it is often compared, the late-19th-century Gilded Age was riddled with monopolies. Steel and the railways were two of the most consequential. Powerful firms could set prices at will.

They also had more control over their workers than anything any of us have ever experienced.

For example, the Pullman Palace Car Company built and ran the town of Pullman, south of Chicago, for its railway workers. In common with many successful capitalists, the firm’s founder, George Pullman, personally designed the place to test his theories about how to improve the human condition.

Things did not go well.

The Pullman Strike

Pullman forbade his employees to own their own homes in the town, which he ran as a paternalistic dictatorship. The Pullman Company supplied all utilities and owned all retail outlets. With this monopoly, Pullman manipulated prices freely, just as it did in its railway business.

In early 1894, Pullman unilaterally reduced its workers’ wages … but not their rents, or the prices of gas and water.

The American Railway Union (ARU), led by Eugene V. Debs, quickly organized the enraged workers. (Debs later ran for president as a socialist five times; President Woodrow Wilson imprisoned him for sedition.)

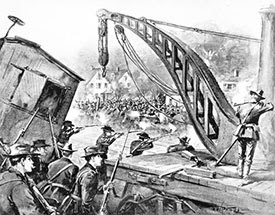

In June, under the ARU’s guidance, the Pullman workers launched a crippling strike that shut down the U.S. railway system west of Chicago. It eventually involved 250,000 workers in 27 states.

The press portrayed the strike as organized by immigrant rabble-rousers who had brought socialist and anarchist ideas with them from Europe.

|

In mid-July, President Grover Cleveland ordered U.S. Attorney General Richard Olney to find a way to end the strike. (Outrageously, Olney, a former railroad attorney, still received a $10,000 annual retainer from the Chicago, Burlington and Quincy Railroad, on top of his $8,000 federal salary.)

Olney and the railway companies called in the U.S. Army and United States Marshals, who shot 30 workers to death and wounded 57 more before it was all over.

Did You Know…

Congress quickly voted to make the first Monday in September a national holiday called Labor Day. President Cleveland signed the law six days after the end of the strike. He hoped to assuage the concerns of nervous workers in other parts of the economy.

In fact, the U.S. already had an informal workers’ day — May 1, still celebrated nearly everywhere else in the world as International Workers' Day.

Cleveland felt that celebrating labor on May 1 would strengthen the U.S. socialist and anarchist movements. He also wanted to discourage solidarity between U.S. and Canadian and European workers, who celebrated May 1.

That’s why we celebrate Labor Day in September.

Lessons Learned?

The Gilded Age was like ours in many ways.

Powerful monopolies and bigger-than-life businessmen … massive inequality of wealth and political influence … disorganized workers, increasingly frustrated by the imbalance of power … contempt for immigrants.

The country survived … but not by doubling down on the dog-eat-dog attitudes of the Gilded Age.

It did so by making sensible reforms that met the needs of as many Americans as possible. In fact, conditions in the U.S. after World War II, our period of greatest national prosperity and unity, were essentially the opposite of the Gilded Age.

That suggests to me that there is a way to make this country great again: Learn a bit of history, and act on that knowledge.