At the end of January, Bank of America’s high-grade credit strategy team, headed by Hans Mikkelsen, claimed that inflows to high-grade bond funds and ETFs would taper and decrease 39% during 2018 to $197 billion, meaning that monthly inflows, running at close to $30 billion before the report was published, will fall to just $10 billion by year-end.

This forecast was based on the assumption that investors would want to take less risk in the high-grade space with rising interest rates and tight credit spreads, which have resulted in diminishing fixed income returns and increasing rate volatility.

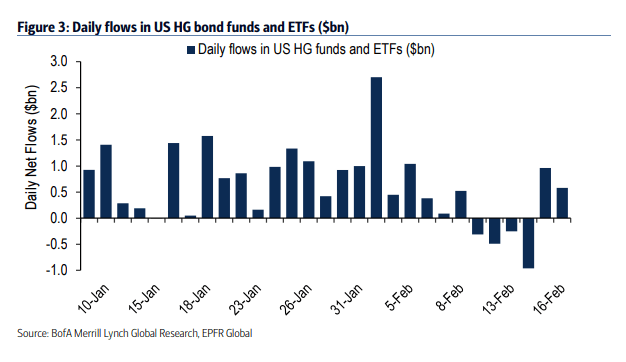

As it turns out, at the beginning of February this trend started to emerge. After reaching a record of $38.4 billion in January, significantly up from the $22.2 billion net inflow in December, and the previous record of $36.3 billion printed in March 2017, during the first few weeks of February the high grade-bond market experienced a "mini-tantrum."

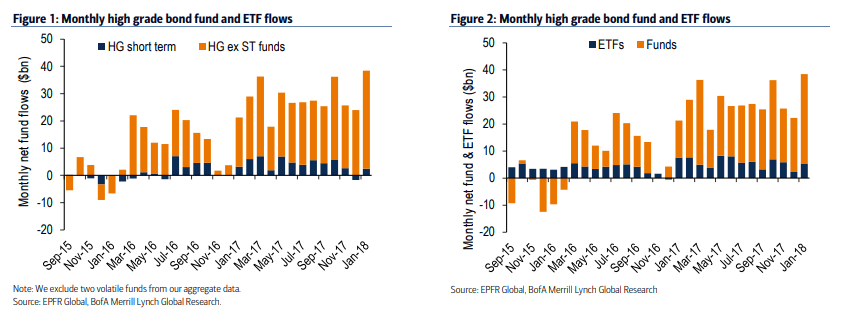

During the second week of February, there were four consecutive days of outflows from high-grade bond funds. Although this trend had reversed by the end of the week (15th and 16th of Feb), it is "consistent with our expectations of tapering inflows to high grade given diminishing fixed income returns, increasing rates vol and the decline in equities."

Still, despite this mini-tantrum, it seems that investors are still extremely keen on bonds as an asset class. Throughout January, bond funds and ETFs attracted a record $38.4 billion, and high-grade bond fund inflows dwarfed their ETFs counterparts by six-folds with $33 billion of inflows compared to $5.4 billion for ETFs. Of this total, the vast inflow was driven by $36 billion of inflows away from the short-term category, with short-term funds/ETFs contributing the remaining $2.4 billion.

It's not entirely clear however who is buying these funds. Several weeks ago Bank of America reported on the Flow of Funds data from the Federal Reserve, which showed that the “Household Sector” accounted for more or less all inflows to mutual funds across asset classes between the first and third quarter of 2017. Almost all of the inflows were to funds that invest in debt securities.

What the bank's analysts find interesting about these figures is that the "Household Sector" accounts not only for just retail investors but also all other categories that the Fed is unable to classify, such as foreign investors:

"We think the Fed is having difficulties identifying foreign investors that invest in US fixed income through bond funds, and thus many end up in this residual household category."