The 10-year interest rate hit the critical level of 3% this morning.

And this is the highest level it’s been since 2014 – four years ago. . .

A couple months back, I highlighted the correlation of the rise in the Fed Funds Rate (FFR) and the Interest Payments Due on the U.S. National Debt. And as President Trump and Congress are showing no signs of slowing down their borrowing – this debt service cost will only keep rising.

But the U.S. Treasury will get funded no matter what – foreigners will buy the debt, or the Fed will print dollars to do it. Either way, they will borrow – no matter the cost.

But individuals and companies that borrow aren’t as lucky. . .

They’re forced to pay the higher interest payments.

So, with interest rates moving up, it would be smart to see what businesses and sectors are most vulnerable to rising yields.

And for this, we need to look at the LIBOR rate. . .

LIBOR stands for London Interbank Offered Rate and is a benchmark rate that the world’s leading banks charge each other for short-term lending. It’s the first step when calculating interest rates on various kinds of loans – whether government bonds, corporate bonds, mortgages, or student debt.

You might have heard about LIBOR over the last few years. Many of the world’s leading financial institutions were caught manipulating the rate for years to profit and protect themselves.

Here’s an example: back in the 2007-08 financial meltdown, Barclays Bank manipulated the LIBOR downward. This lowering of rates in a time where rates were trending higher because of global bankruptcy risks gave off the impression that they were ‘less’ risky.

The LIBOR Scandal is known as one of the greatest financial crimes in history. And banks were hit with many billions in fines.

Bust despite this, the LIBOR rate continues it’s role as the primary lending benchmark rate through-out the world. . .

History of the LIBOR rate show’s that it’s always been slightly more than the Fed Funds Rate. But it usually follows the Fed’s lead up or down.

With the Fed raising short term rates, and the U.S. 10 yield eclipsing 3% – debt tied to LIBOR will be greatly affected.

JP Morgan – using the Fed’s own data – calculated that there is about $7.5 trillion in pure LIBOR-related debt.

Syndicated loans (loans offered by a group of lenders to provide funds to a single borrower) are 97% tied to the LIBOR rate.

Both corporate and non-corporate business loans and commercial mortgages are about half tied to LIBOR. . .

To put this in perspective, a 35-basis point increase could raise business loan interest costs by $21 billion.

So, with yields rising – both on the short end and the long end of the curve – this could hurt the business sector.

Which means the stock market. . .

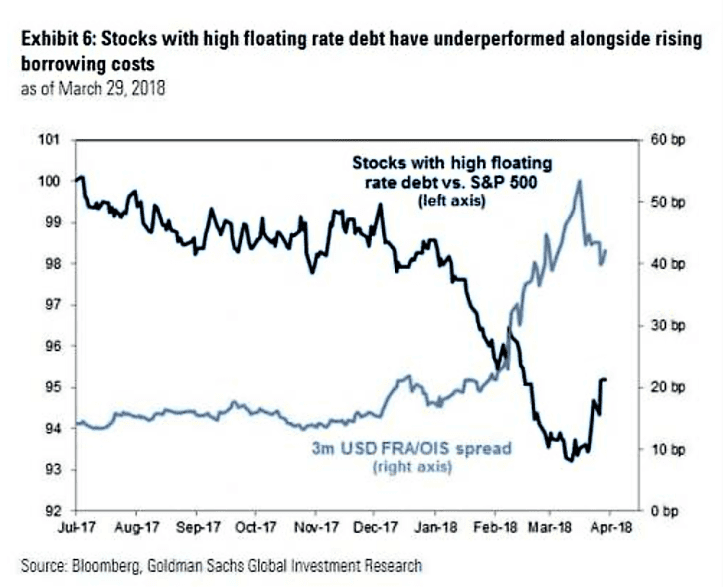

Just look at the stocks with high-floating rate debts (adjustable interest) having underperformed the S&P 500 when borrowing costs rose.

The correlation is unmistakable. . .

Unless the Fed completely reverses their tightening strategy – which they inevitably will – things are only going to get worse.

During the low interest rate years, companies could pile on debt to buy time. But once interest rates start rising – things start getting difficult for them.

I think this is becoming more apparent – for instance, Chapter 11 bankruptcies have soared to 7 year highs.

Companies will buckle underneath the rising debt costs.

But if things get too bad, the Fed will come in to save the day by lowering rates to keep these “zombie” companies going.

They always do.

Author Bio: