RV Capital Co-Investor Letter for the first half ended June 2020, titled, “Business Owner TGV vs. the DAX.”

Q2 2020 hedge fund letters, conferences and more

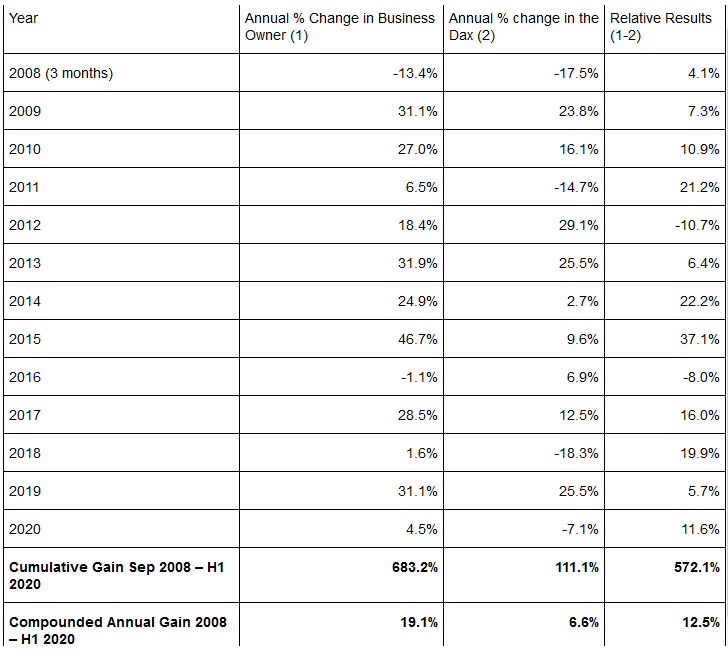

Business Owner TGV vs. the DAX

Dear Co-Investor,

The NAV of Business Owner was €777.13 as of 30 June 2020. The NAV increased 4.5% since the start of the year and 683.2% since inception on 30 September 2008. The DAX was down 7.1% and up 111.1% respectively. The percentage changes differ from the changes in NAV due to disbursements from the fund related to taxes.

About the First Half

As you can see from the modest gain in the unit price since the start of the year, it was an uneventful six months.

I jest.

The last six months were the most astonishing I have experienced as an investor. It was said after the Lehman bankruptcy that the economy went into cardiac arrest, but compared to what happened in March, it was positively dynamic. Aeroplanes continued to fly, stadia were filled, and people went to the doctor. Who would have thought that the revenue for vast swathes of the economy such as hotels, restaurants, passenger airlines and concert venues could go to virtually zero?

The crisis also turned upside down many of our assumptions on how companies fare in a recession. Supposedly weatherproof businesses such as quick service restaurants (“after all, people always have to eat, don’t they?”) suffered, whilst sales of some big ticket items (the first to suffer in a recession normally) such as high-end gym equipment boomed, as people kitted themselves out to socially distance. Everything was Topsy Turvy.

It was a time, when we saw the best of humanity – not just the doctors and nurses, but also the cleaners, lorry drivers and supermarket cashiers that kept essential services running – as well as the worst. When people view the clincher argument against facemasks to be “they only help protect other people,” you know we may be, to use the technical term, “totally screwed”. A case study of both extremes is Amazon. The work of Jeff Bezos and his associates to keep households supplied with essential goods was nothing short of heroic. The press coverage of Amazon, which was negative across the board, was nothing short of disgusting.

At least one of life’s great mysteries was finally solved: What would people do when the end of the world was nigh? It turns out they raided supermarkets for flour and cocooned themselves in their kitchens to bake. Who would have predicted it? My go-to was sourdough bread in case you were wondering.

A Look in the Mirror

I would rate my own performance during the panic as, at best, average. I was tentative when I should have been bold. I preferred to add to existing holdings rather than make new investments. I held back some cash when I should have been all-in (whereby in my defence, I wanted to have cash available to be able to support our companies though ultimately it was not needed).

There was one thing though that I got right – selecting and nurturing an investor base that was not fazed by the March drawdown. There was not a single redemption in the March quarter. The majority of investors simply sat tight. For them, March’s drawdown is no more than a statistical curiosity. A minority of investors – a significant minority - increased their investment. In fact, I had investment requests in March than any prior quarter. They now sit on spectacular gains. I salute their bravery. In hindsight, it always looks easy and obvious to invest when prices are rock bottom, but it is anything but. This is why I urged you in my March Memo to commit to memory your emotional response to the panic. It is soon forgotten.

I have the Great Financial Crisis to thank for building the right investor base – Business Owner was started on 30 September 2008, two weeks after Lehman went down. I saw first-hand how many formerly well thought-of funds were liquidated at the bottom of the market. The fund managers lost their businesses and reputations, and their investors’ losses were locked in at the worst possible time. The manager lost. The customer lost. Relationships were destroyed. It was a lose-lose in every imaginable respect.

The terrifying thing from the perspective of a young capital allocator was that whilst in some cases, the fund managers only had themselves to blame (the use of leverage was the most common cause), in other cases the ruined fund managers had done nothing wrong from an investing perspective. There is always an element of randomness to share prices, but in a crisis, this is doubly so. Some had massive drawdowns simply through bad luck. Share prices in their (former) holdings quickly rebounded, but the damage had been done.

What they did get wrong was having the wrong investors on the bus, a mistake I promised myself not to make. This is why I insist on meeting all investors in person before they invest and why I endeavour to build direct relationships with all my investors. It is also why I refuse to take capital from intermediaries such as fund of funds, IFAs, banks, and insurance companies. My approach does not scale but has the advantage of providing a stable base of capital. The upshot is nobody lost money. A minority made money. And Business Owner lives to fight another day. It is a win-win in every imaginable respect.

Lessons Learnt

It is too early to write about lessons learnt from Covid-19. For all we know, the worst of the pandemic still lies in the future. In the case of the Spanish flu of 1918, the second wave in the Autumn was far deadlier than the first wave in the Spring. As such, this is a topic I may come back to when we can be sure the virus is behind us (as one day it will).

There does seem to be one lesson that investors are drawing from the crisis, which I feel is the wrong one: the optimal investment strategy is to own digital-first companies.

Yes, digital-first companies have been the most obvious beneficiaries of the virus. Owners of these stocks did not just get lucky. The trends towards e-commerce or cloud computing, for example, were firmly established well before the virus took hold. What the virus did was bring these trends forward. As such, to the extent someone owned Zoom prior to the crisis, their returns were not necessarily dumb luck. Had they held on long enough, they might have ended up with a similarly sized business as today. It would have just taken a few more years to get there.

However, it is worth remembering that crises come in different shapes and sizes. This crisis impacted the physical world to the benefit of the online world. The opposite scenario is equally possibly. In fact, in January I wrote that the greatest longtail risk to the economy was from a virus… of the computer variety (so near to glory, and yet so far). I still believe a computer virus is a major risk and strongly recommend reading “Sandworm” by Andy Greenberg to get up-to-speed on how fragile the Internet is.

A computer virus could shut down the online world, and we would have to venture back into physical world to, for example, meet a partner. I apologize if I have terrified my younger readers. If your worst-case scenario for Zoom does not factor in an extended period with zero revenues, frankly, you have not been paying attention. I wonder too, how well many of the digital-first companies would have fared if they, not their offline counterparts, had been forced to shut up shop. Many went into the crisis with large operating losses and thinly capitalised balance sheets. It was noticeable how many scrambled to raise capital in March despite supposedly being “crisis winners”.

The big lesson from this crisis, or any crisis, is that the unexpected sometimes happens. The correct investment strategy is not to try to predict the unpredictable (which is futile), nor is it to just own Internet companies (which is simplistic). It is to own companies that have sufficient reserves of strength to weather any crisis.

Our Companies and Covid-19

I normally discuss the development of our companies over the prior year in my first half letter, but it feels more apt to discuss how they have fared in the crisis. A one line summary of 2019 is: the positive trends continued. Now for 2020.

As is abundantly clear from the section above, I had neither the ability nor the ambition to predict Covid-19 when I bought the stakes in the companies making up Business Owner (although I did select them in the knowledge that there would occasionally be major shocks to the economy). If you put together a portfolio of companies without a specific risk factor in mind, how it affects them is likely to be random. So where did the chips fall? In aggregate, we were neither particularly lucky nor unlucky. We own some companies that are obvious beneficiaries of the crisis and some that are apparent losers.

The obvious winners include Wix, Facebook and AddLife. Wix saw a boom in new users as small businesses scrambled to build an online presence. Facebook saw an explosion in usage and perhaps benefited from an improvement in its public perception as people relied on its infrastructure to stay connected with their friends and families. AddLife saw a massive increase in demand for personal protective equipment as well as diagnostic tests both for Covid-19 and its related medical conditions. Of the three, only AddLife was seen as a winner from start to finish. For a short time, both Wix and Facebook saw massive share price declines (in both cases due to their exposure to “SMB” – small and medium sized business). They neatly illustrate the randomness of share prices in a crisis.

I do not wish to dwell any further on the winners though. Covid-19 is a stress test. The far more interesting case studies are the companies that were exposed to that stress.

Credit Acceptance

As a lender to subprime borrowers, Credit Acceptance was perceived as a crisis loser. At the trough, the share price lost over 50% vs the start of the year. This was most likely driven by the prospect of increased customer defaults as unemployment soared, declines in used car sales as dealerships were forced to shutter, and its decision to delay the publication of its first quarter report.

Fears around all three seem to be misplaced. Adjusted earnings per share were up by 20% in Q1 including an estimate for additional losses for Covid-19 (which since turned out to be too high). Unit growth was down by 22.3% in March and April on the prior year, which is impressive if you consider the economy was almost completely shuttered. By May, unit volumes were up 21.8% and likely accelerated further in June. The SEC explicitly invited companies to delay their quarterly reports and the decision to do so was wise. It allowed the company to allocate scarce management resources to the more of important tasks of taking care of customers and protecting employees. Moreover, when it did report in June, there was much richer data available on the impact of the crisis.

Ryman Healthcare

As an operator of retirement villages, Ryman Healthcare was/is very much in the eye of the Covid-19 storm. In contrast to the Spanish flu, which primarily attacked young adults, Covid-19 has the highest fatality rates in older people. This has made it especially lethal when it infiltrates aged care facilities. It seems likely that aged care facilities are the ground zero of this crisis, comparable to the World Trade Centre post 9/11.

Given the above, I understand that many investors decided a retirement village operator was most certainly not the way to play the pandemic. Respectfully, I disagree. A once in a generation crisis is also a once in a generation opportunity. Ryman seized it. It locked its villages down early. It tested everyone with a legitimate reason to enter the villages. And it took great care of its residents – workers on idled construction sites instead delivered groceries to village residents.

To date, Ryman has kept Covid-19 out of his villages. There is an element of chance to this, and it cannot be ruled out that this will still be the case by the end of the crisis, however I feel certain the conclusion will be that Ryman did everything humanely possible to keep residents and staff safe. I was in regular contact with Ryman’s senior management team throughout the crisis and heard about this first-hand.

From a financial perspective, it is still a bit too early to say what the repercussions of the crisis are. Resales came to a virtual standstill during the lockdown, then roared back when the lockdown was loosened. Its New Zealand construction sites were idled, whilst the Australian ones remained open. The impact of the dip in resales and delays in construction strikes me as transitory, whereas the gain in reputation should be permanent.

Trupanion

On the spectrum of companies impacted by the crisis, Trupanion’s position was the most ambiguous beforehand. Healthcare is an essential service, but hey, we are talking about animals, right? One investor confidently predicted to me that claims would drop during the lockdown (as people stayed at home), but churn (policy cancellations) would spike afterwards as people looked to tighten belts. It turns out he got things backward. Claims were mostly unaffected – it turns out that if Snoopy is not feeling well, it takes more than a life-threatening virus to keep owners away from the vet. Churn cratered as the Covid-19 catastrophe brought home to people the value of having, well, catastrophe insurance. Overall, I expect the decline in churn to be transitory but the trend towards health insurance for pets to be reinforced.

Grenke

Whilst an argument could be made that all the above companies will benefit both in the short-term and the long-term, the initial evidence is that Grenke will benefit more in the long-term than the short-term. Only the long-term moves the needle on a company’s intrinsic value, so the difference is cosmetic.

The loan loss rate rose to 2.2% in Q1 (vs. 1.5% in the prior year) and is likely to remain at an elevated level in the coming quarters. This will burden the immediate earnings development but is far from a level that could impact the company’s long-term survival or ability to write new loans.

New business volume was down by roughly half in April and whilst it has improved recently, it remains at a depressed level. Despite this, there is a decent chance its revenue will be flat for the year as, like most lending businesses, the bulk of revenue comes from loans sourced in prior years. In this respect, revenue is subscription-like. The big difference to other subscription businesses is that the customer must first declare bankruptcy to “cancel the subscription”.

Overall, I expect demand for small ticket equipment to return at some point and when it does Grenke will be there as one of a shrinking number of financing options for SMBs.

Summary of the Covid-19 Impact

It is great to see companies like Wix and AddLife do well in this crisis, however they were not really stress tested. What brings me far greater pleasure is to see companies firmly in the eye of the storm, like Ryman or Credit Acceptance, do well. Neither company nor any of our other businesses turned loss-making or required additional capital. It is still early days though and I am conscious that we could well be closer to the start of the crisis than the end.

Back in China

After a multiyear hiatus since the sale of our stake in Baidu, I am delighted to say we are back in China.

Towards the end of the half-year, I bought a stake in Prosus. Prosus is a Dutch holding company that was spun off one year ago from the South African Naspers, however its main asset is a 31% stake in Chinese Internet mega cap Tencent. At the time of writing, the market value of this stake accounted for 120% of Prosus’ market capitalisation. For this reason, I view our investment in Prosus primarily as an investment in Tencent.

About Tencent

Tencent belongs to the first wave of Internet companies. It was listed in on the Hong Kong Stock Exchange in 2004. It was founded by Pony Ma, who continues to be CEO and a large shareholder. Like all of Business Owner’s investments, Tencent is run by a passionate and engaged CEO.

In common with many Chinese Internet companies, Tencent started out as a loose copy of a Western business. In Tencent’s case, it launched QQ, a pc-based chat client based on the now largely forgotten ICQ. Like all successful Chinese Internet businesses, rapid iteration and adaptation meant QQ quickly ceased to look anything like ICQ.

Like most early Internet businesses, Tencent struggled initially to hit on a money-making formula. The bulk of revenue came from reselling SMS. If you read its earliest annual reports, the impression is of a company trying out lots of different services, none of which really hit paydirt. This experience would set it up to succeed spectacularly when the smart phone revolution came along a decade later. One business that did do well and came to be the main source of revenues was publishing online games and later developing its own. Although Tencent is thought of primarily as a social network, online games are still Tencent’s largest business accounting for over one third of revenues and an even greater share of gross profit.

Prior to the start of the smartphone era, Tencent was a successful business and was one member of BAT, China’s initial triumvirate of Internet giants equivalent to FAANG. Of the three, it was arguably the biggest beneficiary of the smartphone revolution. It turns out that chat is more central to the smartphone than it was to the PC, and the smartphone greatly expands the online gaming market. Tencent adapted QQ to the smartphone with considerable success – today, it has 650m MAUs. In what was probably the most inspired strategic business decision of all time, it also set up an internal competition to develop a mobile-first chat app from the ground up. The winner was Weixin, known as WeChat in English, and the rest is history. Today, the combined MAU of Weixin and WeChat are 1.2bn, making it the world’s second largest social network after Facebook.

Weixin is a so-called super app. In contrast to WhatsApp, for example, Weixin integrates many different services such as hailing a taxi, booking a doctor’s appointment, or paying for goods and services. The roots of this design philosophy can be traced back to Tencent’s earliest days. Given Weixin’s many use cases, it is variously described as a “remote control for life” or an “operating system”. Services sit on top of Weixin in the same way as PC software sits on top of Windows. Weixin’s secret sauce, in my view, is the tight integration of payment. Transacting with millions of merchants and service providers on Weixin is as simple and seamless as hailing a car with Uber in the West. Weixin itself is free to use but is monetised through advertising and a take rate on payments, amongst others.

Tencent reports in three main segments: Value Added Services (“VAS”), Fintech and Business Services, and Online Advertising. The bulk of VAS revenues come from the sale of virtual items in online games as well as the non-advertising revenues from Video and Music subscriptions as well as the sale of eBooks. The bulk of Fintech revenue comes from payments commissions but includes Tencent’s nascent efforts in other financial services as well as cloud services. Online Advertising includes ad revenue from the Moments tab, where users can follow friends, Official Accounts, where users can follow celebrities and brands, and from Tencent Video.

Tencent’s segment reporting does not, in my view, throw much light on the underlying profitability of its individual businesses. The organising principle is type of revenue, thus standalone businesses straddle different segments, making it difficult to disentangle them. For example, Tencent Video’s subscription revenues are booked in VAS, whereas its ad revenues are booked in Online Advertising. Furthermore, each segment bundles developed and presumably profitable businesses with younger and presumably loss-making businesses. For example, in the Fintech segment, payments are bundled with its start-up cloud business. It is thus difficult to say what the underlying profitability is, i.e. excluding investments in younger businesses. All that can be said is that in aggregate Tencent is spectacularly profitable with a group operating margin of 31%.

Why invest in Tencent now?

I first heard about Weixin on a trip to China in 2013 and have followed Tencent closely since. As it is a good fit with Business Owner’s investment criteria, given the passionate CEO and the inherently wide and growing moat of a social network, a legitimate question is why it took me so long to invest. There were three main reasons.

Reason no. 1: Accounting

For a long time, I struggled with Tencent’s accounting and, to an extent, still do. I took the time to explain the segment reporting above to illustrate how intransparent it is. However, I have come to realise, a degree of intransparency is not always a bad sign, counterintuitive as its sounds. Amazon, for example, has never been particularly forthcoming about where and how it earns money.

The question is whether a company is under- or overstating the profitability of its core businesses. As with Amazon, my sense is that it is the former. It would be easy to bundle loss-making businesses in their own segment and show higher “adjusted” earnings if Tencent wanted to. Its motivation is most likely to avoid unwanted attention from regulators, customers, and competitors, as well as to provide aircover for initiatives with a long investment phase, such as Video, Cloud, and Financial Services.

Reason No. 2: Gaming

I was also put off by the dependence on online gaming. As a non-gamer, I did not understand the business well (why would anyone pay real money for virtual jewellery?) and was concerned that it was too hits-based. Today, the proportion of revenue from online gaming has fallen due to growth in advertising and payments. More importantly, I have come to understand, thanks to observing my children, what an amazing business online gaming is. Successful game franchises are long-lived and Tencent either owns or has licenced many of the best ones for China including Honor of Kings and PUBG. Furthermore, Tencent is the partner of choice for overseas games developers looking to enter the Chinese market.

Reason No. 3: Capital allocation

Finally, I have gained a greater appreciation over the years of how important capital allocation is in general and how advantaged Tencent’s position is in particular. As the dominant social network in China, Tencent gets an early look at which start-ups (be it in games, services, or whatever) are gaining traction. Its ability to give investee companies a privileged position in Weixin makes it a preferred investor. By the same token, a privileged position in Weixin greatly improves the odds of the company becoming a commercial success. It is a flywheel that has proven spectacularly successful. Tencent owns substantial stakes in a long list of valuable businesses both inside and outside of China including Epic Games, SEA Ltd, JD.com, and Meituan. I estimate the value of the disclosed investments at over HK$ 900 bn (just under HK$ 100 per share), one fifth of Tencent’s market capitalisation.

To sum up, Tencent is a better business than I initially thought (gaming franchise, capital allocation). I feel more comfortable using its reported earnings as a basis for a valuation. And I now see its investment portfolio as a large and ongoing source of value creation.

Tencent's Fair Value

What might a back-of-the-envelope fair value calculation look like? I estimate Tencent can grow revenues to RMB 1 trillion in 2025 (19% CAGR) and achieve an underlying Free cash flow margin of 30%. With a 20x multiple, this results in a fair value of RMB 6 trillion. If I compound its investment portfolio at 20% p.a. (made up of intrinsic value gains of the existing holdings as well as new investments financed out of free cash flow), I get to a value of RMB 2 trillion. This implies an enterprise value of RMB 8 trillion in 2025, equivalent to HK$ 900 per share using an exchange rate of 0.9. I use round numbers for simplicity, but in any case, there is enormous uncertainty when peering five years into the future. As always, things will likely work out differently than planned. The important thing is that the assumptions are correct directionally.

I realise not everyone will agree with valuing investment gains from businesses that may not even been created yet. However, given Tencent’s obviously advantaged position as a capital allocator and stunning track record, it would be remiss to disregard them.

Why invest via Prosus?

I prefer Prosus to Tencent as it trades at a large discount to its NAV. At €175bn, the market value of Prosus’ stake in Tencent alone accounts for 120% of its market capitalisation. In addition, Prosus has stakes in several other Internet businesses including 31% of Mail.ru (social networking), 22% of Delivery Hero and 55% of iFood (food delivery) and 100% of Avito and OLX Group (online classifieds). Including these as well as Prosus’ net cash position, the market value-based NAV rises to EUR 200 bn, implying a holding discount of 31%.

Old hands will, no doubt, argue a big holding discount is not unusual for a conglomerate, and there is no reason for it to close. They may be right, but I prefer to think it through from first principals rather than assume holding discounts are a law of nature.

There are three main rationales for holding discounts: tax disadvantages, excessive costs at the holding level, and poor capital allocation. In each case, the value creation at the investee level does not flow through to the investor – be it due to tax, to holding costs, or to squandering investment gains – making it less attractive to own the holding versus the underlying assets. Accordingly, investors demand a discount.

In the case of Prosus, none of the three justify such a large discount, in my view. Based on my (admittedly limited) understanding of the way Prosus has been structured from a tax perspective, there would be no capital gains tax were it to sell its holdings. Should it pay those gains out to investors, they would largely be treated as tax-free reductions in capital rather than dividends as long as Naspers remains a large shareholder in Prosus. I see no obvious tax disadvantage vs owning Tencent directly.

Prosus has high holding costs in absolute terms at around EUR 100 m, but relative to the NAV of EUR 200 bn, they are small fry. If I capitalise them at 20x, they might justify a 1% discount. Moreover, the more fundamental question is whether Prosus adds value at the holding level, i.e. how good is the capital allocation?

To date, Prosus’ capital allocation has been good. Excluding gains from Tencent, which I view as a lucky punch, it calculates its IRR to be 18% p.a. since 2002. This includes some prominent exits (Souq to Amazon, Flipkart to Walmart, and MakeMyTrip to Trip.com) as well as appreciation in its core holdings. For sure, it has been a golden period to invest in e-commerce companies, so I doubt the future will be as rosy as the past. Furthermore, I do not view Prosus to be as advantaged in allocating capital as Tencent (though its reputation, network and permanent capital base perhaps confer some minor advantages). However, I struggle to see a scenario where capital allocation is a big enough source of capital destruction to warrant a large discount to NAV.

Early Stage Investing in Public Markets

Tencent is an example of a company with a fully developed moat and a degree of maturity in its core business. If things pan out as I hope, the returns will be good, but not life changing. Life changing returns come from identifying the Tencents of the world much earlier in their lifecycle and, equally difficult, holding on to them, as Naspers, to its credit, did.

With this in mind, I recently picked up the S/1 for Lemonade, a provider of home insurance and, since this week, pet insurance, and would-be disruptor of the insurance industry. What follows is quite negative on Lemonade. If you are a shareholder in Lemonade, I would not pay too much attention to what I write. It is not a business I know well, and I am really using it as a vehicle to hone my thinking on early stage investing in listed companies. Moreover, as I later argue, any weaknesses in its business model today may, perversely, increase its chances of success in the long run.

The premise of Lemonade’s business model is that the insurance industry is “broken” as the customer is pitched against her insurance company in a zero-sum game in which the former wins by minimizing claims payouts and latter wins by maximising them. Furthermore, systems are expensive and antiquated leading to high costs that are ultimately borne by the customer. Lemonade aims to disrupt the insurance industry by better aligning underwriting incentives between insurer and insured and taking cost out by, for example, replacing insurance representatives with AI bots.

I am sceptical about their ability to do either with the current business model. Better aligning incentives leans heavily on the use of reinsurance and charitable donations. The idea is that the former negates the risk of undercharging the customer whilst the latter negates the incentive of overcharging her (as surplus underwriting profits are donated to a charity designated by the customer). The problem with this is that reinsurance is not new, and donations are expensive. I am also sceptical about the upside from AI bots. Bots possibly save cost in processing claims, but better still for the customer would be not having to file a claim in the first place as, for example, Trupanion makes possible by integrating with the vet’s practice management software.

What I also dislike is Lemonade’s claim to be a more ethical business given the charity angle. The implicit idea is that business is evil and can redeem itself through a charitable donation. I believe the primary mechanism for societal progress is businesses profitably offering customers better products more cheaply, not charity. Charities do a great job filling in the gaps where markets fail, but business does the heavy lifting (not to mention financing the charitable giving). As usual, Charlie Munger put it better:

I believe Costco does more for civilization than the Rockefeller Foundation. I think it’s a better place. You get a bunch of very intelligent people sitting around trying to do good, I immediately get kind of suspicious and squirm in my seat.

Once I got over my initial scepticism about Lemonade, it struck me that its basic premise - that the insurance industry is not optimised for the customer - is likely true. If so, which company is most likely to find a solution? Is it an incumbent that is heavily invested in the status quo? Or Lemonade, a company that seems to have a near unlimited ability to raise capital and a licence to lose money and experiment indefinitely? Clearly the latter.

If this is the case, maybe analysing today’s business model is the wrong way to approach this type of situation, in the same way that analysing Berkshire Hathaway's textile operations was the wrong way to approach Berkshire in the 1950s. The correct approach then was to analyse Buffett’s willingness and ability to take capital out of a failing business and put it into more promising ones. In the same vein, if a company is trying to re-engineer a broken industry, rather than analysing the business as-is, a more promising line of enquiry is analysing what it might become. This entails judging whether it has deep resources, a licence from its investors to lose money, and a culture that encourages experimentation and failure. I guess this could be Lemonade. As an aside, I think I just described Amazon in the early 2000s.

To be clear, I do not view an abundance of capital and willingness to experiment to be sufficient reason to invest in a company. What I miss at Lemonade is the kernel of an idea (however unformed), which - if you squint - you can imagine creating a new paradigm in decades to come. I may be missing something, but I do not see its approach as disruptive.

There is, perhaps, a middle ground where a company has a kernel of an idea that works (but is not fully figured out) and a long runway to experiment. In this situation, what feels like a long shot - Netflix, 10+ years ago - is closer to an inevitability than it appears. If you thought video on demand was going to be a big thing ten years ago (and frankly why would you not have?), there was a point in time where it became almost impossible to imagine a company other than Netflix cracking it. I suspect this point was longer ago than investors who, like me, missed Netflix care to admit.

To date, Business Owner has only once invested in what I would describe as an early stage, listed company. It was Trupanion, a company creating the category of health insurance for pets, that I described in my 2015 letter. So far, it has worked out well as an investment, indecently well. I expect to make more of this type of investment in the future.

It is important to note that an early stage, listed company is likely to have several characteristics that will leave traditional value investors shaking their heads in disgust. Its moat is likely to be prospective as opposed to developed. It is likely to be loss-making as it invests towards an, as yet, undefined future. And it is likely to trade on a high multiple of revenue as its current customer base is a small fraction of the ultimate market opportunity. However, I am happy to break with the consensus of what constitutes a value investment, if need be. In my ten-year memo, I wrote:

To have a chance of replicating the past decade’s performance in the new decade, the implication is that I will again, at a few crucial moments, have to jettison beliefs that today seem incontrovertible. By definition, I cannot know what these are. If I did, I would have already got rid of them.

I suspect more fully embracing businesses at an earlier stage of their lifecycle is one such moment.

RV Capital’s 2021 Annual Gathering in Engelberg

All and any physical gatherings are cloaked in enormous uncertainty today, and RV Capital’s annual gathering in Engelberg is no exception. All I can say with certainty is that if the meeting does take place, it will be on the weekend of 16-17 January 2021. Mark your calendars accordingly. Details on the event are on my website here.

I will not open registration until there is more clarity on whether it will be possible to travel. Doing so beforehand makes little sense. To remove at least some uncertainty, I will not impose a limit on the number of registrations this year unless mandated to by the Swiss authorities. In other words, if you want to come and are able to come, you are welcome to come.

This article first appeared on ValueWalk Premium.