Success is a complex thing. We do not live in a meritocracy. A lot of people in positions of power or relative success have been helped along the way by luck, discrimination, the invisible influence of privilege, chance encounters.

Sometimes hard workers get further than those with natural talent who take it easy; sometimes vice versa. Sometimes super-talented, hard-working people wind up in careers of unfulfilling mediocrity because they don’t have the confidence or the chutzpah to make or take the opportunities that others might leap at.

Q2 hedge fund letters, conference, scoops etc

But knowing that professional hierarchies by no means reflect on the relative intelligence or capability of those involved does not invalidate the work or position of successful people. Rather, it should be seen as an opportunity to acknowledge and work with your flaws, collaborate with a community of folk with complementary skills to your own, and to consider the world of work and business from a perspective of process and mutability rather than fixating on absolutes.

So where does imposter syndrome come into all this?

Imposter syndrome is a complex phenomenon in which sufferers believe themselves to have fluked their way into their position; to actually lack any of the intelligence for which they are praised and rewarded. It’s complex partly because it’s so subjective. If you believe you have low self-esteem then you believe that you’re an imposter in your position, and there’s not much anyone can say to change your mind.

Why does imposter syndrome happen? Partly, it’s a result of some of those same ‘quirks’ of our society that stand in the way of a meritocracy. The invisible undercurrents of privilege and hegemony, and patriarchal structures that have evolved to make bizarre inequalities seem normal (such as men being paid more than women in similar positions, a phenomenon both caused by and perpetuating the idea that men are more valuable and competent).

As such, it should be no surprise that women suffer imposter syndrome more frequently than men – although perhaps not to the extent that you would imagine. Two-thirds of women and just over half of all men suffer from imposter syndrome each year. But it was the highly gendered values of American society that inspired the original research into imposter syndrome in the 1970s and ‘80s.

“Despite outstanding academic and professional accomplishments, women who experience the imposter phenomenon persist in believing that they are really not bright and have fooled anyone who thinks otherwise,” wrote Dr. Pauline R. Clance with Suzanne Imes in a paper at Georgia State University in 1978. “These women find innumerable means of negating any external evidence that contradicts their belief that they are, in reality, unintelligent.”

In particular, Clance and Imes note that “early family dynamics and later introjection of societal sex-role stereotyping” make imposter syndrome the norm, rather than a freak occurrence, for women in our communities.

One such woman was Dr. Valerie Young – and it is thanks to some of the solutions that she uncovered that you can help yourself to recover from imposter syndrome today (and once you’ve done so, go to work dismantling the structures that make it so prevalent!)

“One day while I was sitting in class,” writes Dr Young, “another student began reading aloud from an article by a couple of psychologists from Georgia State University, Dr. Pauline Rose Clance and Dr. Suzanne Imes, titled, “The Impostor Phenomenon in High Achieving Women.

“My head was nodding like a bobble-head doll’s. “Oh my God,” I thought, “she’s talking about me!” When I looked around the room, everyone else—including the professor—was nodding too.

“I couldn’t believe my eyes. I knew these people. I’d been in class with them, I’d taught alongside them, I’d read their work. To me, they were intelligent, articulate, and supremely competent individuals.”

Dr Young and her classmates established a support group for each other, but it didn’t take long for Young to realize that group therapy was not the answer. Unfortunately, when you find yourself in a room full of gifted people who believe they are imposters, it only exaggerates your feelings of inadequacy!

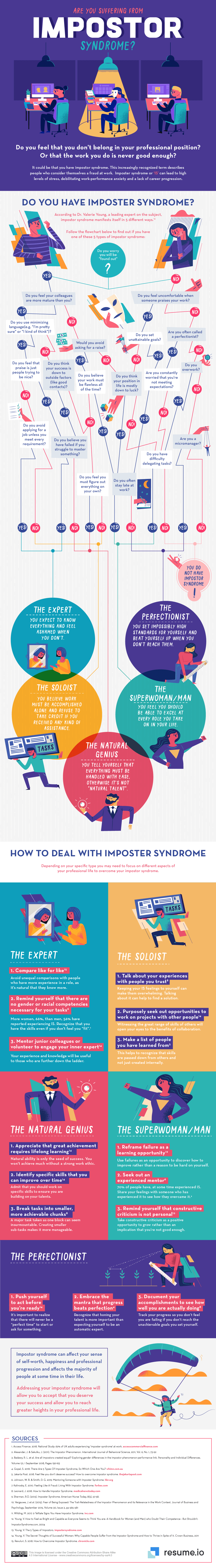

While it is useful to acknowledge that you are afflicted by imposter syndrome, awareness and self-knowledge can be more effective remedies than ‘sharing.’ And Dr Young figured out five different types of imposter syndrome sufferer who can take different approaches to deal with their condition. Each is based on a different definition of the ‘competence’ that imposter syndrome sufferers feel they lack.

For example, the Expert category refers to people who feel that if they don’t know absolutely everything, then they don’t deserve the position they’re in. The Expert may hold back from applying for positions where they meet most but not all of the requirements, because they are afraid to be called out on the box that they can’t yet tick. They may feel inadequate or threatened when other people in their workplace – particularly those lower in the hierarchy – know more about a subject than themselves.

People who suffer in this way can benefit from recognizing that no two people have the exact same knowledge. Everybody has their own specialism, and within those specialisms each has their own interests and experience. Discovering somebody who knows something you don’t, or just a gap in your knowledge, is an opportunity to learn, grow, and collaborate.

This new visual guide to imposter syndrome includes a tool to help you diagnose whether you might be a sufferer, and if so what type you might be. It is also packed with advice on how to cope with and recover from the syndrome. Because you don’t have to be the best of the best to be where you are – but you do need the confidence to make the most of your particular skill set.