Global corporate debt is now over $29 trillion, with nearly one-quarter maturing within five years. How dangerous are soaring corporate debt levels for global economic and financial stability?

On the Forum Agenda:

- Rise of emerging-market corporate credit risk

- Growing preference for debt in the capital structure

- Immediate and long-term refinancing solutions

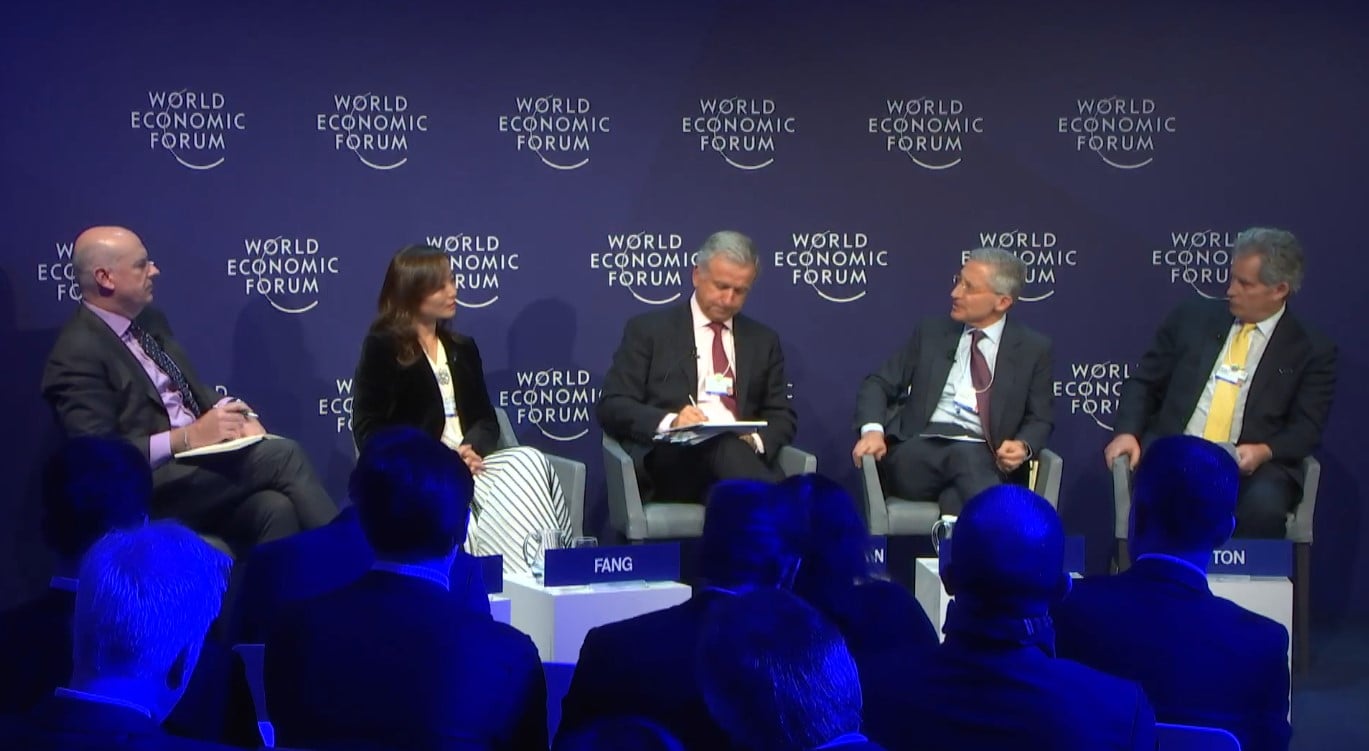

Speakers

- Karen Fang, Managing Director; Head, Americas Fixed Income, Currencies and Commodities Sales, Bank of America Merrill Lynch, USA; Young Global Leader

- Joshua S. Friedman, Co-Founder, Co-Chairman and Co-Chief Executive Officer, Canyon Partners, USA

- Felipe Larraín Bascuñán, Minister of Finance of Chile

- David A. Lipton, First Deputy Managing Director, International Monetary Fund (IMF), Washington DC

Moderated by

- Gerard Baker, Editor-at-Large, Wall Street Journal, USA

Davis 2019 – When The Corporate Debt Bubble Bursts

Transcript

Joshua S. Friedman: We did get a little preview of that in the beginning of 2016 the end of 15. The Fed started raising rates. People were worried about deflation from China. Oil prices were going down. And we saw quite a correction in the market although it found its footing and recovered more than recovered and we got another preview of it last month. I wouldn’t. A bubble is something that can burst my entire career and I suspect everyone’s lifetime in this room. Bubbles that burst of financial calamities usually take place when you have a combination of excessive leverage with a liquidity mismatch. So you own illiquid assets and you have liquid liabilities and there’s gigantic leverage on it. That was the banking and that was the global financial crisis and then those things get leaked out into not only in the banking system of the banking system is particularly bad but even if it’s not in the banking system itself if it’s other institutions.

What’s happened since 2008 has made that much less likely. And that doesn’t mean that we don’t have a lot of overheating for all the reasons you said which I’ll come back to. The reason that’s less likely today is that in the last 10 years thanks to regulation thanks to the desire of Bank of bankers not to have a recurring nightmare commercial bank balance sheets are awfully awfully good. If you look at the high yield market commercial banks used to own between 10 and 20 percent of all the product and they made very active markets using their own capital. Today those banks use none of their own capital to take positions. And it’s not just because of the Volcker Rule. They don’t do it anywhere and they act as actual agents for their clients as opposed to competing with them as principals. So there’s good and bad to that. The bad news is so structurally they’re pretty solid.

The bad news is that if you look at the consumers who do own these products mutual funds, ETFs, hedge funds and others. The desperate search for yield against a zero interest rate standard for governments has caused passive vehicles to do very well. And there’s been this one way train of capital into vehicles that want to look like the High Yield Index. The benefit for rates going down. And as long as you keep ringing the bell and feeding the dog then it’ll lookee salivating every time you ring the bell. And we’ve been ringing the bell non-stop with mutual funds to own fairly illiquid assets because the issue of mismatchi.e. we have to honor daily requirements for capital if we have redemptions even though we have illiquid assets hasn’t been an issue because it’s been a one way flow of capital in and the capital comes in those buyers have to buy because they want to look like the index or something measure off the index. So that’s what happens when you artificially set interest rates at a very very low number.

The flip side of that is when and when that reverses you get to see the consequences of owning illiquid assets with liquid liabilities. And it’s even exaggerated by the fact that the commercial banks aren’t making markets with their own capital. So if you’re seeking a bid suddenly and we saw outflows the beginning of 16 we saw it again in the last month. You get some significant problems with pricing along the way. You do get some of those debt bubble type characteristics so for example there becomes incredible competition among institutions who were pension funds and endowments and others who need that yield to survive to buy things and you get all that kind of late cycle overly bullish behavior that causes mispricing. You get poor covenants you get. You get the debt markets version of fake news which is pro forma earnings you note and covenants are not set off of but this set off of some fakie but that manufactured back God only knows what you have. You have a frenzy of purchase of leverage loans that are covenant light.

They literally have no covenants and then on top of it when there is a problem. Because the markets are so forgiving and they really want to they want to be able to borrow money out the the private equity controllers of the companies can act particularly abusive toward the creditors and then in the very late cycles of like it’s like when the fall of civilization happens and people start killing each other. You get credit or on credit or violence and you start getting CDX wars and other kind of you know credit default swap wars and other things. So we definitely had a healthy dose of that which made the pár loan market and the pár high yield markets at least for us not very interesting places to reside. But that’s very different from a bubble a bubble is when you have mismatch and leverage when you have when you have mismatch spread out through a bigger and bigger part of the system but you don’t have the leverage. Everybody bears the brunt of that adjustment and it doesn’t damage your financial institution. So you’re less likely to have those extreme consequences. Thank you Jim we’ll come back to some other things to say to David. You’ve lived through a significant number.