Gary Alexander, senior writer at Navellier & Associates, offers the following commentary:

Consumer price complainers seldom cite prices that decline dramatically, but let me rehearse a few.

I recall flying coast-to-coast in 1975 for about $900 a ticket. It’s half that now. A long-distance phone call could cost $2 a minute in prime time. Now, it’s essentially free. I paid $475 for a new Encyclopedia Britannica set in 1972. A far more complete Wikipedia online is essentially free.

Q3 2022 hedge fund letters, conferences and more

I paid $3,000 plus $500 for a printer in 1984 and it blew up every time I wrote eight pages or more. Now, I can buy a $399 laptop that stores gigabytes. An early calculator cost $500. The first cellphones felt like a brick (2 pounds), lasted 30 minutes without re-charging, and cost $3,995.

Need I go on?

But let me cite some items that have risen in price in absolute terms, but have actually declined. You hear complaints about them all the time, but I’ll give you the rest of the story, courtesy of a new book, “Superabundance” by Marian L. Tupy and Gale L. Pooley. They measure the amount of time it takes a median-salaried worker to buy a certain product.

Before I cite these examples, let me quote three all-important words at the end of Milton Friedman’s definition of inflation as a “monetary phenomenon” (above). He refers to inflation as “a more rapid increase in the quantity of money than in output.”

Our wealth and output have grown so much in the last 50 years that you can’t measure prices in a vacuum. You must measure our ability to pay those prices.

Here are some widely complained-about price increases of the last year (or the last 25 to 50 years):

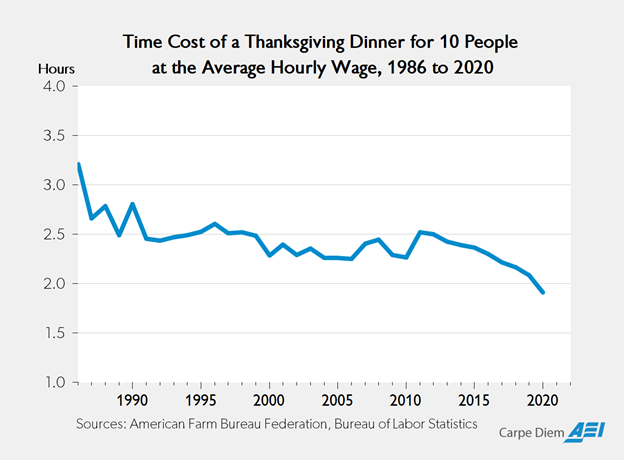

The Cost of a Thanksgiving Dinner.

Unless you were on a remote desert island with no Internet service, you heard stories in the last month about the rapid rise in the cost of a traditional Thanksgiving dinner – this year, and over time.

Since 1986, the American Farm Bureau Federation has conducted an annual price survey of food items in a typical Thanksgiving dinner designed for 10 people with plenty of leftovers, including a 16-pound turkey, a 30-ounce pumpkin pie mix, and lots of other goodies. In nominal terms, the cost of that dinner rose from $28.74 in 1986 to $46.90 in 2020, up 63.2%.

In the same 34 years, inflation rose 135%, so the dinner rose less than half as fast as inflation, but the average unskilled worker put in 3.27 hours of labor for that dinner in 1986, and only 1.67 hours in 2020, or 40.3% less time. Blue-collar workers put in 38% less time for the turkey repast, and skilled workers put in 74.8% fewer hours!

Housing Costs Are Incredibly Higher, Aren’t They?

Superabundance authors say: “Bill Bonner noted that ‘it cost $23,000 in 1970 to put a roof over [one’s] head. Today it’s $240,000.’ What he forgot to mention is that the average house in 1970 was 1,500 square feet. Today it’s closer to 2,700 square feet….

The nominal price of a square foot of house in 1970 was $15.33 and the U.S. blue-collar hourly compensation rate was $3.93, indicating a time price (TP) of 3.9 hours per square foot. In 2019, the nominal price of a square foot of housing was $88.89, and the U.S. blue-collar hourly compensation rate was $32.36, indicating a TP of 2.75 hours per square foot.

Those figures indicate that the price of housing declined by almost 30% between 1970 and 2019.” For skilled workers, the time price decline was 67%.

Television And Other Electronic Prices.

Here’s where the math gets crazy. I paid $500 for my first color TV console set in 1982, and it was a pretty rotten picture by today’s standards. For much less than $500, I can get a fairly large HDTV flat screen now. In 1997, Sharp and Sony introduced their first 42-inch flat-screen TVs for about $15,000 each.

That year the U.S. blue-collar hourly pay rate was $18.12 per hour, which works out to 828 hours to afford this early flat screen. In 2019, a large discount retail store advertised a 43-inch LCD set for $149, with the blue-collar hourly rate averaging $32.36, so it took just 4.6 hours of work to buy that set. It’s 99.45% cheaper, a compounded savings of 26.7% per year.

Using Moore’s law, the transaction costs and storage rates in our computers are falling at similar rates.

So, tell me once again how fast prices are rising.