Famed investor and polymath, Charlie Munger, has recognized our innate “tendency not to learn appropriately from someone disliked.”

Q4 2019 hedge fund letters, conferences and more

The late Lee Kuan Yew, first Prime Minister of Singapore, and one of Charlie’s inspirations, urged us to “benefit from lessons paid for by others.”

Let’s merge those two keen insights and learn a lesson paid by “someone disliked.”

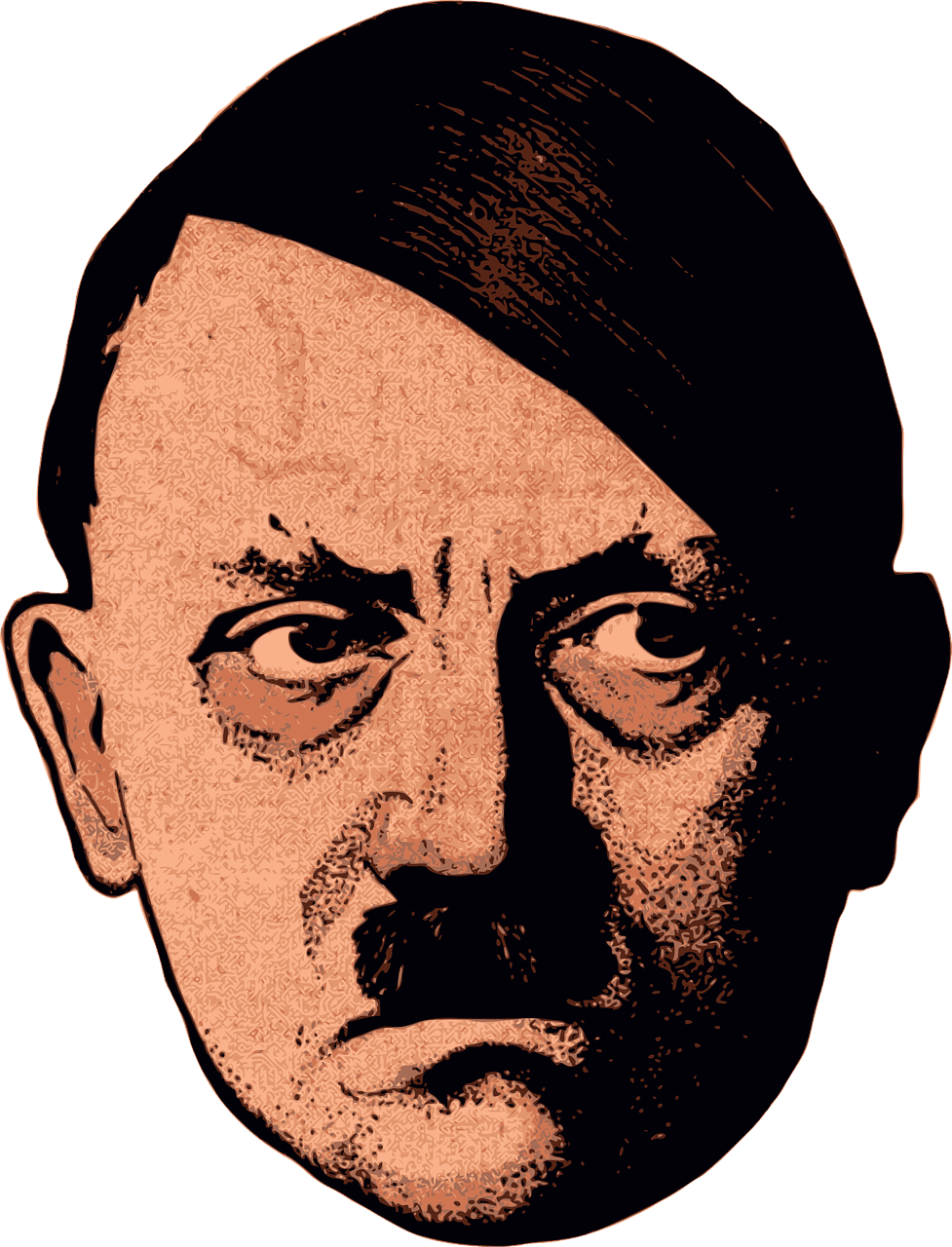

In many people’s books, the most disliked, indeed hated, person in human history is dictator Adolf Hitler.

To be sure, no single individual bears more responsibility for human suffering, death and destruction than Adolf Hitler.

So much so that it is sometimes difficult to remember that he was merely a human being, tormented and embittered: manic-depressive, combat-traumatized and drug-addicted.

Nonetheless he was a skilled and ruthless politician who maintained consistent beliefs which guided his geopolitical decisions, including his decision to wage a war of conquest against Russia.

It was Hitler’s greatest tactical misjudgment, a pivotal mistake which led to untold misery and death for tens of millions of people and Hitler's ultimate defeat and the devastation and partition of Germany.

Hitler believed he could conquer and subjugate Russia.

Why?

Because he was convinced the Russians were an inferior people who would yield to a superior people.

Hitler had a world-shattering blind spot: stereotypes.

Adolf Hitler’s Table Talk

Adolf Hitler held nightly dinners where he opined before friends and staff on any subject he wished.

Hitler’s private thoughts on the Russian people were recorded on July 5, 1941, two weeks into the invasion of Russia, known as Operation Barbarossa:

“In the eyes of the Russian the principal support of civilization is vodka. His ideal consists in never doing anything but the indispensable. Our conception of work (work, and then more of it!) is one that he submits to as if it were a real curse…the Russian will never make up his mind to work except under compulsion from the outside, for he is incapable of organizing himself.”1

Stereotyping peoples and nations was popular and accepted in Hitler’s day. He was not unique; he was a creature of his Zeitgeist. Such thinking dominated even academic and intellectual life.

“Human Heredity” (Grundriss der menschlische Erblichkeitslehre und Rassenhygiene)2 was the standard German genetics textbook of the 1920s and 30s. It was world-renowned, published and republished in successive editions. Translated into English it was well-received in the international medical press.

Hitler read “Human Heredity” during his confinement in the Landsberg Prison after the abortive Beer Hall Putsch. The authors, all noted physicians and geneticists, dismiss “the Russians” summarily:

“The Russians, with their strong infusion of Mongoloid blood, excel rather in suffering and endurance than in the action that brings freedom. They have a cyclothymic nature (in Kretchmer’s sense), with a melancholic fundamental tone. ‘The Russian folk has no wish to rule; it is by temperament passive, rather than gentle, ready to obey—feminine rather than masculine in character.’”

With this stereotype of Russians why would Hitler not contemplate quick and complete victory?

Hitler's Private Conversation with Carl Gustav Mannerheim

On June 4, 1942, less than a year into Operation Barbarossa, Adolf Hitler met clandestinely with Carl Gustav Mannerheim, Commander-in-Chief of the Finnish Defense Forces. Three years previously Mannerheim had staunchly defended against a Russian invasion. In private conversation Hitler pleaded for Mannerheim’s assistance in Operation Barbarossa.

A secret wire recording, the only known audio record of Hitler’s informal speech, reveals Hitler’s shock at Russian military capabilities:

“We ourselves had no precise idea how monstrously this state had been equipped…they have the most extensive armament that could ever be conceived by man. Had someone told me that a state can send 35,000 tanks to the battle, then I would have said, ‘You are out of your mind.’ …we had not thought it possible.”3

Mannerheim, German by descent, was diplomatic and sympathetic but declined to help Hitler in his flagging invasion. Hitler had not helped him in 1939.

Hitler’s blind spot would cost him the war. He had hopelessly misjudged “the Russian.” The Fuehrer who was always right—hat immer Recht-- was wrong. Rational analysis would have envisioned many possible outcomes for Barbarossa, including this most dire one for Hitler: that Russians would fight ably and a two-front war would be catastrophe for Germany.

Thinking Fast and Slow

Our intuitions—System 1 in Daniel Kahneman’s “Thinking Fast and Slow”4—are a mental shorthand which freely categorizes and stereotypes. We come to thoughtful and rational analysis—Kahneman’s System 2—slowly and reluctantly. To be and remain rational, as Charlie Munger and Lee Kuan Yew always instruct, we must resist the relentless pull of mental knee-jerk and gut reactions, like stereotypes. They are nature’s cognitive shortcut, evolution’s autopilot that protects us from the stranger: the human equivalent of a dog’s bark.

The philosopher Umberto Eco attributed the profound emotional power of the wartime film, Casablanca (1942)5, to its brazen stereotypes: rugged American, martial German, charming Frenchman, effete Englishman, mad Russian. One stereotype offends, but a movie awash in stereotypes is alive and credible. We suspend our disbelief. Casablanca recreates our gut-felt reality, though hardly a true one.

Paul Henreid, the third-billed star of Casablanca, forever branded a stiff for playing the cuckolded freedom fighter, Victor Laszlo, protested bitterly in a postwar interview that Casablanca was hopelessly unrealistic; not a scene in it conformed to real life.

He was right: Casablanca is pure melodrama. Not a moment of it could occur in reality. That Casablanca works, as brilliant and enduring art and propaganda, is testament to the enormous power of stereotypes. For Casablanca is, ultimately, a call to arms heard around the world, to defeat Adolf Hitler, whose own stereotype of “the Russian” ultimately cost him the war.

The Lesson we can learn from Adolf Hitler

Adolf Hitler never learned his lesson. He blamed Germany for his failed war.

But we can learn his lesson: our inborn instinct to stereotype the stranger does not work.

In game theory, it’s a lose-lose.

We must recognize our common humanity not merely because it is morally right, but because it works best.

A vital message in this time of crisis.

So Good Will to All.

That it may bring Peace On Earth.

- https://archive.org/stream/HitlerTableTalk/Hitler%20TableTalk_djvu.txt

- Baur-Fischer-Lenz, Human Heredity, London: George Allen & Unwin, Ltd, 1931

- https://www.feldgrau.net/forum/viewtopic.php?t=13647

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Thinking_Fast_and_Slow

- https://biblioklept.org/2013/05/26/casablanca-or-the-cliches-are-having-a-ball-umberto-eco/