Welcome to the third instalment of the Road to Mastery Series, and you can read previous instalments here.

In the last instalment we established that the quantitative elements are the businesses numerical data, which are found in:

- The cash flow statement

- The balance sheet

- The income statement

- The equity statement

And in addition, the company’s annual and quarterly reports will further provide production and unit prices, capacity and costs, etc.

In the 1930s, tangible assets were the main quantitative elements of value Graham and Dodd used to appraise the value of a company.

“The reason: much of the stock market’s capitalization in that era was based on raw materials (mainly mining companies), transportation (railroads), utilities, and manufacturing. All of those industries had significant amounts of plant, equipment, and inventory. Today, service firms dominate the economy, and, even in manufacturing, much of the firm’s capital comes from intangibles-software, acquired brands, customers, product portfolios-that do not appear explicitly on the balance sheet.”

Bruce Berkowitz

Hence, Graham and Dodd encouraged the investor to value a business in three quantitative perspectives:

- Book Value (total assets minus total liabilities)

- Current-Asset Value (current assets minus all liabilities)

- Cash-Value (cash assets minus all liabilities)

And other Value Investors have added another valuation perspective, worthy of consideration, called Enterprise Value (market capital of equity plus long-term debt).

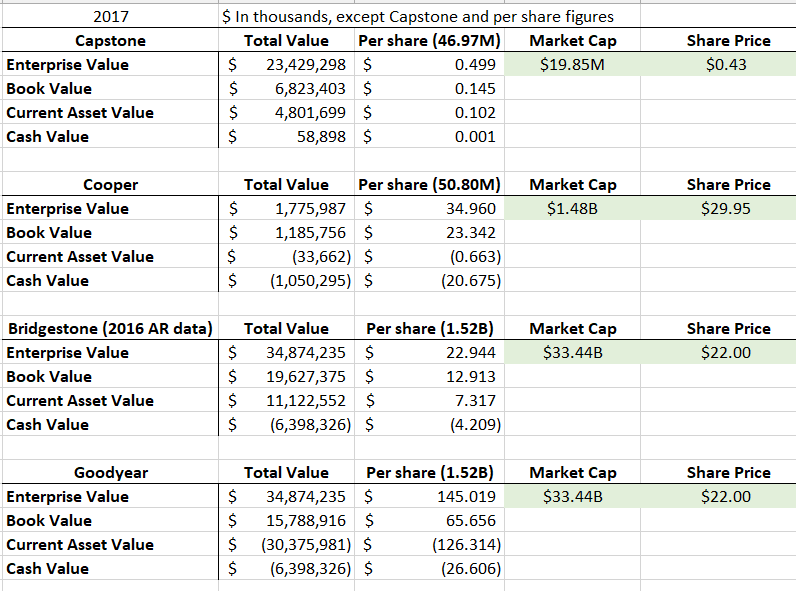

Let’s put these quantitative valuations into practice with companies in the Tire and Rubber industry, which appears to be out of favor with investors.

Companies such as Capstone (NASDAQ:CAPC), Cooper Tire and Rubber Company (NYSE: CTB), Bridgestone Corp., (TYO: 5108 & BRDCY U.S.: OTC) and Goodyear Corp., (NYSE:GT).

Figures correct at 8th of April 2018. Capstone, Goodyear, and Cooper’s figures are from their 2017 annual report, but Bridgestone’s figures are from their 2016 annual report.

All four companies are trading slightly below their enterprise value.

It’s important to note that the above valuations have been based upon the stated values of assets as reported by the company in their respective annual report.

“In most instances, assets are overvalued and liabilities are undervalued in an effort to communicate higher earning power and a stronger financial position.”

C.W Mulford and E.E. Comiskey

Graham and Dodd did recognize that assets values stated on a company’s balance sheet may not reflect their actual realizable value.

Graham and Dodd wrote: (emphasis mine)

The book value of a common stock originally the most important element in its financial exhibit. It was supposed to show “the value” of the shares in the same way as a merchant’s balance sheet shows him the value of his business. This idea has almost completely disappeared from the horizon.

The value of a company’s assets carried on its balance sheet has lost practically all its significance. This change arose from the fact, first, that the value of the fixed assets, as stated, frequently bore no relationship to the actual cost and, secondly, that in an even larger proportion of cases these values bore no relationship to the figure at which they would be sold or the figure which would be justified by the earnings.

The practice of inflating the book value of the fixed property is giving way to the opposite artifice of cutting it down to nothing in order to avoid depreciation charges, but both have the same consequence of depriving the book-value figures of any real significance.

Graham and Dodd’s first observation that the fixed assets, as stated, frequently bore no relationship to the actual cost, is an important observation. This especially occurs in the U.S. where GAAP accounting practices state that a company must report an item of property, plant and equipment to be carried at its cost less any accumulated depreciation and any accumulated impairment losses.

GAAP accounting standards refer to this as the Cost model.

For example, if a hypothetical company purchased land and plant 10 years ago at a cost of $100 million. It will have to state the value at $75 million, assuming, straight-line depreciation charges of $2.5 million per year over 40 years, even though the land value has appreciated in value over that period.

Whereas, a company reporting under the International Accounting Standards (IAS) can choose between using the Cost model or Revaluation model.

IAS 16 states that under the Revaluation model:

an item of property, plant and equipment whose fair value can be measured reliably is carried at a revalued amount, which is its fair value at the date of the revaluation less any subsequent accumulated depreciation and subsequent accumulated impairment losses. Revaluations must be made regularly and kept current.

As a general rule, the main countries adopting the IAS standards are inside the European Union and the United Kingdom and her Commonwealth countries (Canada, Australia or New Zealand etc). Click here to view the map.

For example, that same hypothetical company would state the value of land and plant on its balance sheet at the revalued appraised value, as determined by the standards.

Generally, the assets are stated close to the value they would fetch if sold in their respective markets. As the Tire and Rubber companies covered here operate under GAAP accounting practices, we will skip over further details of IAS 16.

Graham and Dodd went on to explain that the character of the business plays an important part in appraising the realizable value of assets held on the company’s balance sheet.

For instance, if a company operates within a declining industry, then you would write down the value of plant and equipment to a value close to what you’d get if you sold it all for scrap material. By appraising the realizable value of plant and equipment as zero, it reduces your risk of loss, think of it as applying Graham’s margin of safety concept to individual asset values.

And in the other extreme case, where a company operates in a high growth industry, plant and equipment will become outdated quickly, once again the equipment, in particular, is worth very little. And in most cases, a new entrant into the industry will buy the latest new equipment at marginally the same price an incumbent paid for their older equipment.

In our case, the Tire and Rubber companies operate in a mature and low growth industry. Plant, property and equipment (PPE) are stated net of depreciation on the balance sheet, and I have assumed liberally that 90% of the PPE is realizable value.

Example Bridgestone Inc.

Notice, how I appraised the realizable value of Inventories at only 30%, which is too low in our case, but I lowered it to show you how it affects the final total realizable asset value of the company.

Whereas, at 80% of realizable value, the inventory value slightly doubles.

Note: The investor who is devoted to learning the ins and outs of an industry will more accurately appraise the realizable value of assets and liabilities. Hence, an investor who specializes in a particular industry is at a large advantage to the investor who generalizes.

After making the asset adjustments, we now see that no changes have been made to the enterprise value, as we did not adjust the liabilities side of the balance sheet. Liabilities very rarely get reevaluated down, they’re understated most of the time.

Today’s investor is unlikely to find great or even good companies selling for less than book value, if you do, there will be a good reason why.

In Graham and Dodd’s era, the opposite was true.

“In 1932, Graham wrote a series of articles in Forbes, “Is American Business Worth More Dead Than Alive?” in which he chastised company management’s for sitting on troves of cash and investments, and investors for overlooking this value, which was not reflected in the prices of stocks.”

Alice Schroeder

The late Walter J. Schloss, pictured above, was known for only applying these shorthand valuations, and with impressive results.

As Warren Buffett said of Schloss:

“He simply says, if a business is worth a dollar and I can buy it for 40 cents, something good may happen to me. And he does it over and over again. He owns many more stocks than I do-and is far less interested in the underlying business; I don’t seem to have very much influence on Walter. That’s one of his strengths: no one has much influence over him.”

By buying stocks that traded below their book values, Schloss amassed one of the most impressive investment records on Wall Street. From 1956 to 1984, Schloss had earned his investors a 21.3% annual compounded rate of return, whereas the S&P’s had earned only an 8.4% annual compounded rate of return over the same time period.

Can Schloss’s record be repeated if an investor started today?

I’m doubtful that today’s investor can use such a simple investment approach, but another investor, who I respect a lot, Tobias E. Carlisle might disagree.

And I’d recommended you check out Carlisle’s talk at Google titled “Deep Value: Why Activist Investors and Other Contrarians Battle for Control of Losing Corporations.”

Carlisle has demonstrated that the concept reversion to the mean (or mean reversion) applies to stocks.

In Carlisle’s words:

“Which is the idea that stocks that have performed poorly in the past will perform better in the future and stocks that have performed well in the past will not perform as well.”

Mean reversion helps to explain Schloss’s investment record, considering he didn’t pay much attention to earnings.

So far, we have focused solely on the balance sheet analysis – the asset values of companies, and looking for opportunities to purchase stocks trading below their realizable assets values. And this, I believe, is the purest form of quantitative analysis.

In Bruce Berkowitz’s quote at the beginning of the article, he described how service firms dominate today’s economy, and he’s right. It’s important to understand the different economic characteristics of today’s service firms and heavy industry production type companies of the past. Which we’ll cover in an upcoming Road to Mastery chapter, the assessment of competitive advantages.

In the next chapter in our Road to Mastery series, we will look at the earning power and intrinsic value elements involving both quantitative analysis – the return on investment and assets generated by the firm – and qualitative analysis – management’s capital allocation.

Yours in Investing

– Adam

P.S. You can subscribe to the email list to receive videos and exclusive material. Subscribe here.

Article by Searching For Value