Voyager spacecraft have revealed a great portion of the solar system before the internet and new technologies. NASA announced on Sunday that Voyager 2’s Neptune flyby marked its 30 year anniversary. This flyby provided the first close-up look of Neptune, but also the only, as no other spacecraft has visited Neptune since the historic flyby.

“The Voyager planetary program really was an opportunity to show the public what science is all about,” Ed Stone, a professor of physics at Caltech and Voyager’s project scientist since 1975 said in a news release. “Every day we learned something new.”

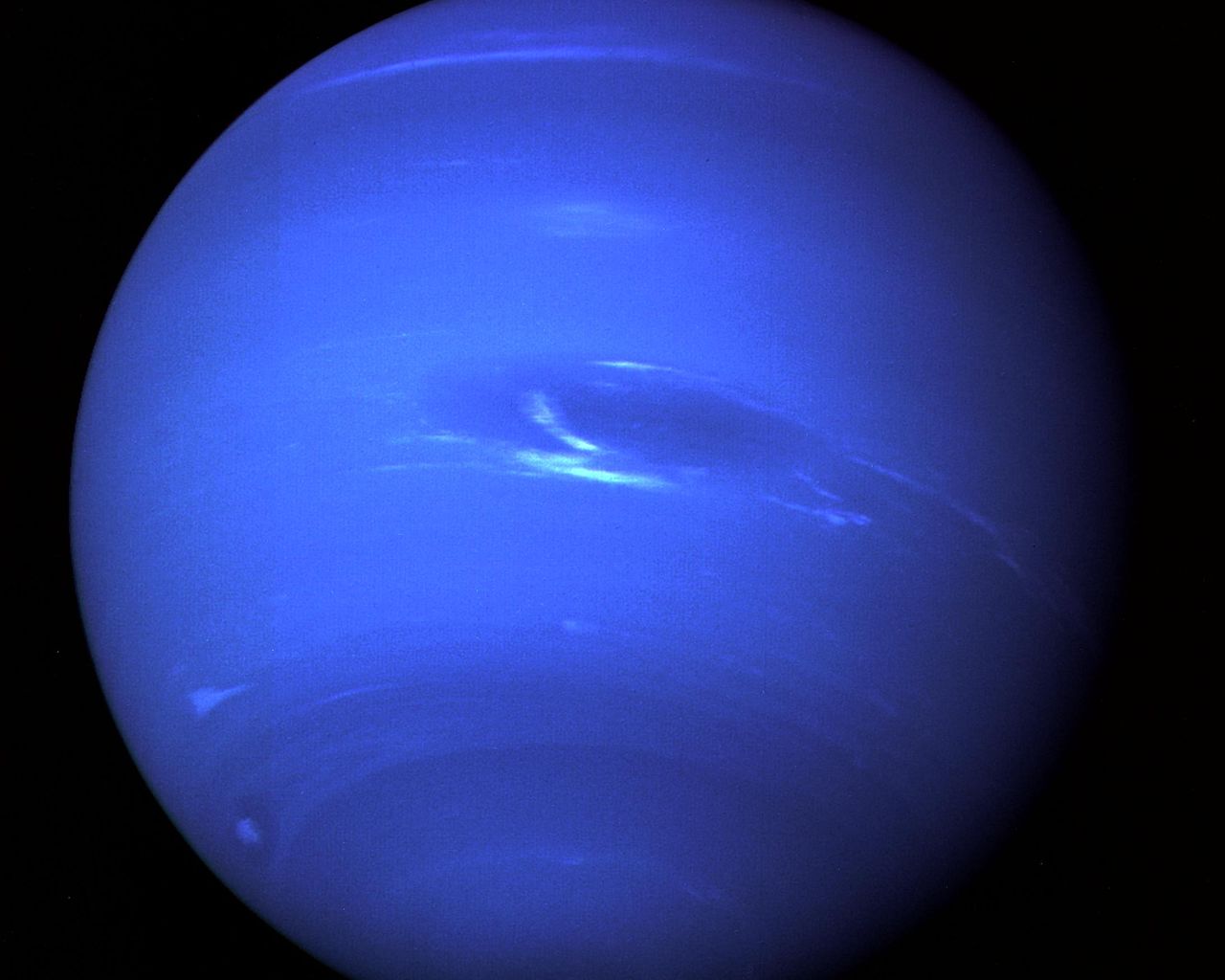

The majestic blue planet looked similar to other giant planets like Jupiter and Saturn, NASA described. The blue color of the planet’s atmosphere indicated that there are vast amounts of methane present. The discovery also described the “Great Dark Spot,” a dark vortex similar to Jupiter’s Great Red Spot, although scientists now have evidence that it’s shrinking.

When the probe approached during the Voyager 2 Neptune flyby, scientists adjusted its speed and direction to also have a look of the planet’s largest moon, Triton. Scientists then spotted evidence of young geological surfaces hinting that its moon may not be as old as the other satellites. The imagery also showed active geysers.

Voyager 2’s Neptune flyby also marked the beginning of the interstellar space exploration for the spacecraft. After 42 years in space, Voyager 2 and Voyager 1 continue exploring interstellar space and sending back data. When the spacecraft visited Neptune, it was located 2.9 billion miles from Earth; today it’s 11 billion miles away.

The tremendous distance between Neptune and the sun allows it to only receive a small portion of sunlight, making it a very cold planet. This distance also meant that it took a lot of time before data from Voyager 2 reached the Earth. The signals were considerably weaker compared to the flybys of other planets closer to Earth.

Scientists use the Deep Space Network also known as DSN, to communicate with the Voyager twins. There are antennas in Madrid, Spain; Canberra, Australia; and Goldstone, California that help enhance signals between the probes and Earth.

When Voyager 2 encountered Uranus in 1986, the DSN antennas were increased from 210 feet wide to 230 feet wide. Other antennas in Parkes, Australia and New Mexico helped to collect data as well.

“One of the things that made the Voyager planetary encounters different from missions today is that there was no internet that would have allowed the whole team and the whole world to see the pictures at the same time,” Stone said. “The images were available in real time at a limited number of locations.”

The Voyagers still send the data they process through their journey back to the DSN antennas, using 13-watt transmitters, which equals the power necessary to power up a light bulb in the refrigerator.

“Every day they travel somewhere that human probes have never been before,” said Stone. “Forty-two years after launch, and they’re still exploring.”