Tollymore Investment Partners’ letter to investors for the first half of the year ended June 30, 2019.

Q1 hedge fund letters, conference, scoops etc

Dear partners,

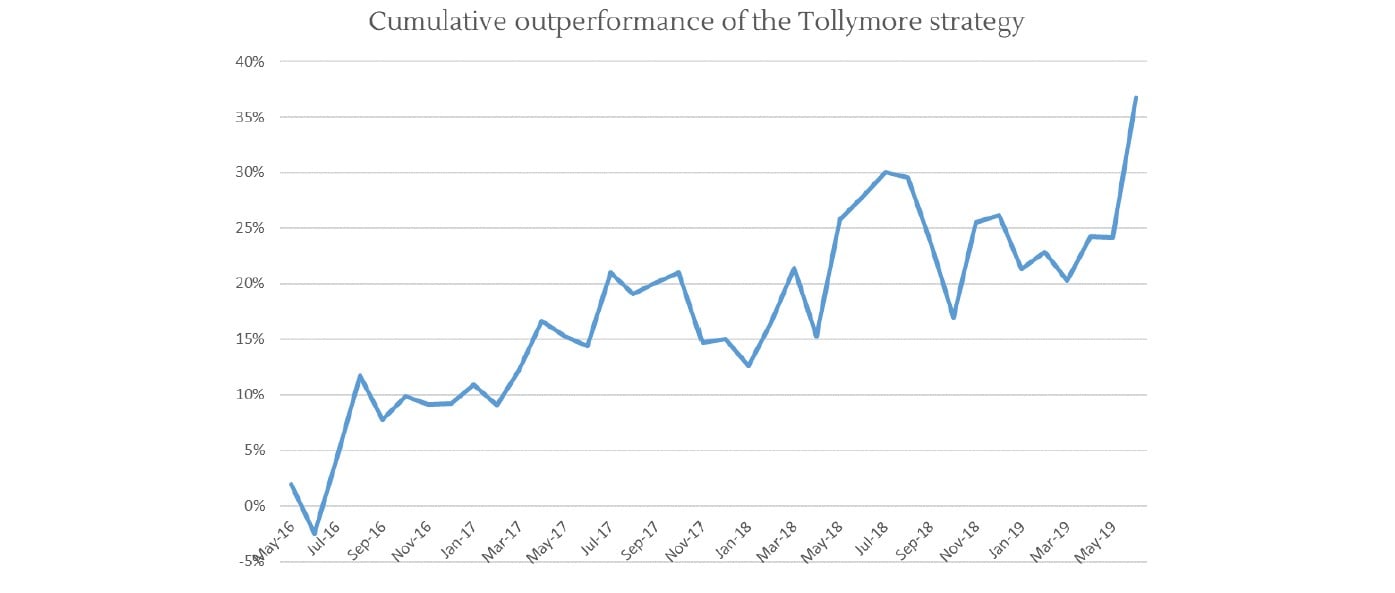

Tollymore generated returns of +20% in the first six months of 2019. Tollymore has generated cumulative returns of +96% since inception, annually compounding capital under its management at +24% pa1.

Q1 hedge fund letters, conference, scoops etc

The rise of the platform and implications for owners

Many of our holdings are platform businesses or linear businesses with underappreciated emerging platform elements. We discuss below the rise of platform businesses, the challenges and benefits that are special to platforms, and the implications for equity owners.

A history of business models

Since the industrial revolution, when the invention of machine tools and the development of steam power marked the transition from hand production to mechanised manufacturing processes, the industrial landscape has been characterised by linear business models. Linear businesses take inputs such as physical production assets and labour to make goods and services that are sold to customers, according to a linear, unidirectional value chain. Think car manufacturers, steel makers and consumer goods companies. Distributors such as Walmart are also linear business models.

In many cases technological advancement has not changed the linear aspect of these companies’ value chains. But in several industries the internet has dramatically lowered distribution costs, permanently impairing capital in those industries that enjoyed economies of scale in physical distribution. Examples include travel agents, newspapers, encyclopaedias, bookstores, video rental and shopping malls. Businesses with high fixed costs of incremental production faced competition from companies enjoying negligible marginal costs of internet distribution.

The transition that many software companies have made to recurring revenue SaaS models has been driven by the opportunity to lower the marginal cost of distribution2 and increase incremental returns on capital. But SaaS companies still operate a linear supply chain. Linear businesses create products and services using their internal resources and means of production. These internal means of production are a constraint on the sustainable growth of the business.

What is a platform?

A platform is a business model that facilitates interactions and the exchange of value between producers and consumers of something that is not produced by the platform itself. Rather than creating value by making and selling things, platforms provide a mechanism for exchange. As such, platforms are much less capital- and labour-intensive than linear businesses. Platforms generate revenues by capturing a share of the transaction value their network enables. Producers in a platform accept an additional cost of unit production in return for the larger volume opportunity that a platform affords3. As such platforms’ breakeven points tend to be at a larger scale than linear businesses.

The economic characteristics of platforms

While the internet has lowered the costs of distribution for many businesses, platforms also have very low marginal costs of production, driving superior unit economics relative to linear businesses. Access to these superior economics are clearly desirable, but they are elusive. Building a successful platform necessitates solving a chicken-and-egg problem of having enough producers to attract consumers and vice versa. Without adequate scale and liquidity, the value to users will be lower than the cost of participation. It is this dynamic that makes platform businesses more difficult to build from a standing start vs. their linear counterparts. Once past the tipping point at which user value is greater than the cost to participate, network effects can take hold to rapidly increase the per-user value of the network4.

In addition to network effects, successful platforms benefit from producer switching costs. Consumers provide non-monetary benefits to producers in the form of reviews, ratings and other feedback such as likes and shares. This is an important mechanism encouraging good behaviour and preserving required levels of customer service5. As producers build up this goodwill asset, the costs of leaving the network and establishing a reputation from scratch increase.

The challenges in building and protecting valuable platforms

One of the principal risks associated with linear business oligopolies is antitrust. The objective of antitrust is to promote fair competition for the benefit of consumers. Traditional monopolists control the means of production. They earn supernormal profits by restricting output, charging anticompetitive prices and minimising consumer surplus. Platform businesses do not own the means of production, but simply the means of connection. Platforms do not control the prices and outputs of producers. But by facilitating more touchpoints between consumers and producers they can increase competition, to the ultimate benefit of the consumer. The goal to increase platform scale benefits both its owners and users. Platforms are therefore characterised by an alignment of interest between shareholders and customers that is not the case in traditional linear monopolists. A regulatory intention to curb a platform’s dominance could have the undesirable effect of harming consumers’ interests.

Platforms make fragmented supply available to consumers in one place. Consider consumers wishing to find the best price for a hotel room. There is an opportunity cost associated with manually finding the owners of that inventory and comparing availability and pricing. Conducting that price comparison exercise on TripAdvisor is a more efficient process. And price transparency leads to a more competitive outcome for the consumer. The platform increases choice and saves the consumer time and money. And the more scale the platform has the greater the choice, and the more competitive the price. In this way platforms grow by delivering more value to their users, rather than by controlling the supply chain. However, while these academic considerations may be logical, until the regulatory regime evolves to be suitable for 21st century business models, incumbents will use arguably unfit-for-purpose antitrust frameworks to make life difficult for dominant platforms such as Airbnb and Uber.

Implications for owners

Winner-take-most economic outcomes6 imply a race for scale, leading to potential battles for dominance. If access to financing is inadequate, or efforts to monetise the network are premature or clumsily executed, the platform may not acquire the requisite scale to enjoy the fruits of market dominance. With supportive owners emerging platforms can avoid the pressure to generate short term profits to maximise total long-term value creation. eBay entered China in the early 2000s and made the mistake of charging commissions to sellers immediately. By keeping Taobao free and by allowing buyers and sellers to communicate with each other (unencumbered by eBay’s desire to prevent transactions outside of the network), Alibaba was able to grow its relevance and benefit from stronger network effects. Alibaba also introduced Alipay, which held customer cash in escrow accounts until buyers verified product receipt. We see parallels with the way in which Sea Limited is growing its Shopee ecommerce platform in Southeast Asia. It is adopting a patient approach to monetising its network7 in order to build non-replicable platform scale and liquidity. It is allowing suppliers and consumers to communicate with each other8, and is overcoming trust hurdles with the Shopee Guarantee9. Shopee is also lowering the friction of ecommerce by integrating its AirPay business10.

Appraising addressable markets when the future ≠ the past

Aswath Damodaran, a respected finance professor at the Stern School of Business and considered an academic authority on company valuation, wrote a paper11 in 2014 in which he dismissed the private business value of Uber at the time of $17bn. By making assumptions about Uber’s potential market share and addressable market, which he defined as the global taxi industry, Professor Damodaran estimated Uber’s value to be $5.9bn. Bill Gurley, a partner at venture firm Benchmark, and Uber investor, published an article12 in response in which he contested that Damodaran had vastly underestimated Uber’s addressable market. Gurley argued that Uber’s potential market is greater than the taxi market due to a superior experience vs. traditional taxis (cheaper, shorter pick up times, more convenient payment methods, greater safety and trust). As such the relevant addressable market was not just the taxi industry, but included public transport, walking, rental cars and driving owned vehicles. Today Uber’s market cap is $75bn, more than four times the company’s private business value five years ago. The outsized return on investment for Uber’s owners was made available in part because of the market’s failure to look beyond the incumbent industry in determining the prospects of those disrupting it. Airbnb is another prominent example of a platform which has expanded the addressable market for lodgings; it has opened an entirely new source of supply (spare rooms and empty homes), therefore growing largely through addressable market expansion rather than market share take13.

So addressable markets can be underappreciated due to a rigid appraisal of incumbent demand. They can also be underappreciated when there exists the potential to leverage the strength of the network to invest into adjacencies. Uber is leveraging the supply side of its network to expand into food delivery with UberEATS. TripAdvisor is leveraging the demand side of its network to expand into attractions and restaurants. TripAdvisor has a rare opportunity to circumnavigate the chicken and egg problem associated with the development of strong platform business models by tapping into to its existing demand in hotel and connecting it to acquired or developed supply in dining and experiences. For both restaurants and attractions, the number of reviewed items is multiples higher than the number of bookable items, and we expect low penetration rates of bookable inventory to provide a long volume growth runway. TripAdvisor is leveraging existing behaviours: people already book tickets to museums or visit famous landmarks and make restaurant reservations. But TripAdvisor is investing in an opportunity to reduce transaction friction by making it easier for customers to find, review and book restaurants and attractions. In doing so it can bring vast untapped supply into its existing travel ecosystem. Crucially, this supply is large14 and fragmented, making its aggregation within a platform valuable.

Valuing platforms

Perhaps the single biggest potential source of platform business undervaluation is the market’s application of linear business prospects to a set of outcomes which could include exponential value growth15. Linear businesses’ customer acquisition efforts result in singular relationships per customer added. Recurring revenue business models may lower the cost of customer acquisition and retention, but they still result in a singular profit stream associated with each customer. When platforms acquire users, whether they are customers or producers, those users form relationships and transact with the existing users in the platform. As the number of users grows arithmetically, the number of potential relationships and interactions grows exponentially. And due to the very low marginal costs of distribution and production, profit margins can expand materially.

The application of linear growth expectations to platform businesses therefore implies a failure of the platform to facilitate, nurture and monetise these potential interactions. Once we understand the dramatically lower cost of growth for these businesses, we should question the relevance of previously accepted valuation methods. Over the last decade Mastercard has compounded its earnings per share at 20% pa, and its share price has grown 30% pa. Ten years ago, Mastercard was available for sale at a mid-teen multiple of its per share earnings. An investor could have paid 80 times the company’s after-tax profits and still achieved an opportunity cost of investing of 10% per year for the next decade. The availability of this opportunity to public equity investors implies a dramatic underappreciation of the exponential growth properties of successful platform companies.

Sotheby's: one of the world’s most enduring platforms

We initially acquired our ownership of Sotheby’s in May 2016 for $28.7 per share. In June 2019 Patrick Drahi announced the takeover of the company for $57 per share and we sold our entire interest for $55.5 per share. The annualised gain of our exit price over our initial entry price was +24% per year, consistent with the annualised returns of the portfolio over that period. However, our ownership of Sotheby’s has been the single largest contributor to Tollymore’s cumulative investment results. Portfolio management is responsible for this outsized contribution. This is a pleasing outcome given our efforts to create an environment that allows us to execute a long-term investment programme. Specifically, we have benefited from a set-up that has allowed us to use share price volatility to lower our average cost of ownership. In doing so we have shrunk the risk of permanent capital loss. Assuming an appropriate investment temperament and aligned investment partners, volatility is inversely correlated with risk. The volatility of publicly quoted securities drives our strong preference for public vs. private market investing in the pursuit of acceptable unleveraged investment results. Sotheby’s stock volatility has been driven to a greater degree by large changes in its earnings’ multiple rather than the variability of those earnings, potentially reflecting poor aggregate understanding of or conviction over what this company is worth on a long term, through-cycle basis. Sotheby’s business model embodies a wonderful combination: the provision of enduring services with very high barriers to profitable participation on the one hand, but the delivery of services which are subject to seasonal, cyclical and otherwise unpredictable16 fluctuations on the other. The former allows us to benefit from the intrinsic value compounding of the underlying asset, while the latter affords us the scope to earn an equity return superior to that rate.

Sotheby’s is a 275-year-old global art business whose operations are organised under two segments: Agency and Finance. The Agency segment earns commissions by matching buyers and sellers of authenticated fine art, decorative art, jewellery, wine and collectibles through an auction or private sale process.

The Finance segment earns interest income from the provision of loans secured by works of art. This segment offers advances secured on consigned property as well as general purpose loans secured by property not presently intended for sale (<50% LTVs). Many traditional lending sources offer conventional loans at a lower cost to borrowers than the average cost of Sotheby's' loans. Many traditional lenders also offer borrowers integrated financial services such as wealth management, which are not offered by Sotheby’s. Few lenders, however, are willing to accept works of art as sole collateral; they lack access to market information required to effectively appraise underwriting risk.

There is evidence of the presence of lasting unfair business advantages. Excluding the finance business, the core auction platform has generated historic returns on invested capital of 25-35%. Sotheby’s and Christies have had high and stable market shares for extraordinarily long periods of time. Sotheby’s has pricing power; it charges sellers a c. 10% commission and a buyer’s premium of 14-25% depending on the hammer price. However, in order to win larger or more prestigious consignments, Sotheby’s and Christie’s will often waive the seller commission (and sometimes even share the buyer’s premium with the seller). This is effectively an investment in brand prestige and can be considered part of the cost of acquiring and retaining buyers and sellers. The finance segment is a form of captive financing which has earned mid-high teens returns on equity.

What are the sources of this moat? Sotheby’s business model enjoys barriers to entry facilitated by a duopoly competitive structure, two-sided network effects, a global brand that lowers search costs and elicits a higher level of trust and willingness to pay, and non-replicable heritage. Brand and reputation are arguably more valuable assets in the art market vs. other industries due to the subjective, difficult-to-estimate value of the products being sold. Sotheby’s duopoly with Christie’s should allow the business more freedom to set pricing in order to maximise

volume*price = revenues.

Consignors are often the executors of estates who are responsible for monetising illiquid assets with opaque and objective valuations. They typically have not consigned before and therefore their risk-aversion attracts them to a global brand with a multi-century history and access to the highest quantity of relevant potential buyers. That is: unrivalled platform scale. The finance segment is an important ancillary business for Sotheby’s. It helps to secure and grow client relationships. Sotheby’s has a clear collateral liquidity and underwriting advantage vs. traditional lenders unable to take artwork as loan security.

Most global art transactions are private sales, but Sotheby’s and Christie’s account for more than a third of global auction sales, and 80% of auction sales priced higher than $1mn. Smaller competitors such as Phillips and Bonhams have been unable to weaken the dominance of the big two and penetrate the market for the most valuable works. Changes in the buyer’s premium enacted by one auction house have typically been followed in both directions by the other.

Arguably Sotheby’s’ long-term value creation has been lower than one would expect from such a demonstrably wide moat business. This could be due to value accruing to executives rather than shareholders and a reluctance from prior management to make long term investments into the business, and/or excessive discounting in order to win high profile consignments. One could argue that Sotheby’s’ stagnant profits over the years reflect a failure to exploit the considerable increase in the number of individuals with the financial means to purchase expensive art. Relatively flat global art market sales over the last decade seem at odds with the trebling of wealth owned by the globe’s billionaires over the same period.

Since Tad Smith has taken the helm in 2015 the company has made good progress on capital allocation (scrapping the dividend and making significant stock repurchases at depressed prices) and on investing in digital capabilities and product adjacencies to improve overall SVA of this business. However, little ground seems to be made on employee cost efficiencies and it is disappointing that the company has altogether stopped reporting some of the metrics relevant to these goals17.

When we initially invested we identified some opportunities to improve return on operating expenses: travel and entertainment costs were $17k per employee, ‘professional fees’ were more than $50mn pa, the average employee salary was almost $190k, and management outlined its expectation for mid-single digit declines in headcount. Unfortunately, there is limited financial evidence to suggest that any headway has been made in lowering the fixed costs of doing business. Headcount has continued to increase, average employee costs have risen by 2% per year, and Sotheby’s stopped disclosing several of the above metrics from 2Q 2017.

Nonetheless, there is evidence to suggest that the future economic value that Sotheby’s will generate for owners will be larger than historically has been the case due to (1) the development of ancillary revenue streams outside of the core auction, and (2) the digitisation of the delivery of Sotheby’s’ services.

Ancillary revenue development: Private sales are a low proportion of Sotheby’s revenues today. In 2018 Sotheby’s generated $1bn of private sales, a 75% increase in two years, but still just 16% of consolidated sales. Private sales may be preferred by consignors wishing to preserve anonymity, seeking to minimise costs of the sale18, to test an aspirational price hidden from the public eye or to avoid the publicity of a failed sale. The advantage of an auction is the competitive bidding tension created, and the potential for auction dynamics to lead to irrational bidding strategies to the ultimate benefit of the seller19. Endowment effect20, social proof21 and scarcity22 are all at play.

There may be an opportunity for Sotheby’s to leverage its relationships with consignors and buyers, and its access to data and valuation expertise, to capture a higher share of private sales, still the dominant mechanism for settling art transactions. CEO Tad Smith has outlined his goal of building enough understanding of customers’ preferences to allow Sotheby’s to offer unsuccessful auction bidders the opportunity to buy similar items via a private sale within 24 hours of the auction. Sotheby’s recruited David Schrader from JP Morgan in 2017 to lead a dedicated team with the goal of growing private sales business. We would suggest that Sotheby’s is well positioned vs. private dealers and art galleries in facilitating private art transactions between buyers and sellers given the breadth of its customer relationships, collection of transaction data and ability to offer advisory and financing services.

There are opportunities outside of art too. Sotheby’s already sells furniture, jewellery, wine, cars and watches, and is expanding further. These items are often the gateway into the purchase of works of art.

Service digitisation: The digital delivery of services could make the art market more accessible and lower the costs of doing business. The company is seeing record numbers of new bidders, two thirds of whom are bidding online. Online only sales are generating just 4% of total revenues but are responsible for one third of new customer additions to the company’s database. Art ecommerce growth materially lags retail ecommerce growth. Digitisation is strengthening the network and is creating the potential for an acceleration in revenue and profit growth by increasing the accessibility of Sotheby’s’ services and the competitiveness of its auctions of unique objects (fixed supply and growing demand). Sotheby’s’ capacity to access untapped international demand also improves as it increasingly conducts its business online; three quarters of revenues are generated in NYC and London, yet art has global appeal.

The slowness of art sales to migrate online over the years may be a function of the presence of asymmetric information and value of physical inspection. These do not seem to be surmountable challenges for a business with Sotheby’s’ credibility, valuation advisory resources and increasingly technological solutions to verifying authenticity. The opportunity is reflected in a world in which millennials represent one third of HNW collectors.

Digital service delivery lowers physical venue dependency, requires less travel and less paper processing including catalogue production. Technology lowers the labour intensity of art authenticity evaluation, sourcing consignments23, matching buyers and sellers, and valuation.

Capital allocation and incentive structures are improving. Tad Smith reduced the share count for the first time in ten years. Management incentives are now linked to ROIC, a KPI that was not even mentioned in prior proxy materials. Smith’s future stock awards were linked to high stock price hurdles. The share price had to at least reach $85 by 2020 for him to receive the maximum award.

Competitive discipline seems to be improving. Inventory sales fell by half in 2018, generating most of the operating margin improvement from 16% to 19%, and perhaps suggesting that the company has been more disciplined in its use of auction guarantees. When we initially acquired shares in 2016, margins had collapsed driven partly by a spike in auction guarantees, the poor judgement of which led to a loss on inventory sales.

Management has shown a willingness to invest for the long term. Management has demonstrated an understanding of the company’s unfair business advantages and has deployed capital to strengthen these. Acquisitions over the last three years include:

- The Mei Moses Art Indices, recognised as the preeminent measure of the state of the art market. Previously publicly available, this is now an internal asset.

- Orion Analytical, a scientific research firm which has developed technologies and procedures to verify authenticity.

- Art, Agency Partners, a consulting firm advising art collectors on portfolio strategies and philanthropic matters connected with the arts.

- Thread Genius, an AI start-up which has developed algorithms to identify objects and recommend similar images to viewers. Sotheby’s has been developing an object database which is designed to physically locate objects of interest and match buyers and sellers.

In 2018, Sotheby’s was able to spend $300mn repurchasing shares, almost triple capital investments, and lower its leverage ratio. It did this while delivering a 24% return on shareholders’ capital. This is a very good business.

We also thought it was a very cheap business. Sotheby’s trailing 12-month EBITDA of c. $200mn is broadly in line with its 10- and 15-year averages, an 8% yield to the quoted enterprise value prior to the acquisition. This was the price of a business with a wide, and widening, moat, for which the costs of doing business could decline, for which corporate governance and incentive structures have improved, and with several paths to profitable revenue growth, including the digital democratisation of art increasing auction competitiveness, and taking market share in private sales.

Final thoughts

Tollymore is a multi-decade learning effort. Striving for self-awareness and sound judgement guides our decision making every day. We are grateful for our relationships with intellectually generous peers and investment partners; these help to compound knowledge and improve our chances of becoming just a little bit wiser together, day by day.

Thank you for your partnership.

Mark

This article first appeared on ValueWalk Premium