Tollymore Investment Partners letter to investors for the year ended Decemberr 31, 2020, discussing retail operating systems and shortened supply chains.

Q4 2020 hedge fund letters, conferences and more

Dear partners,

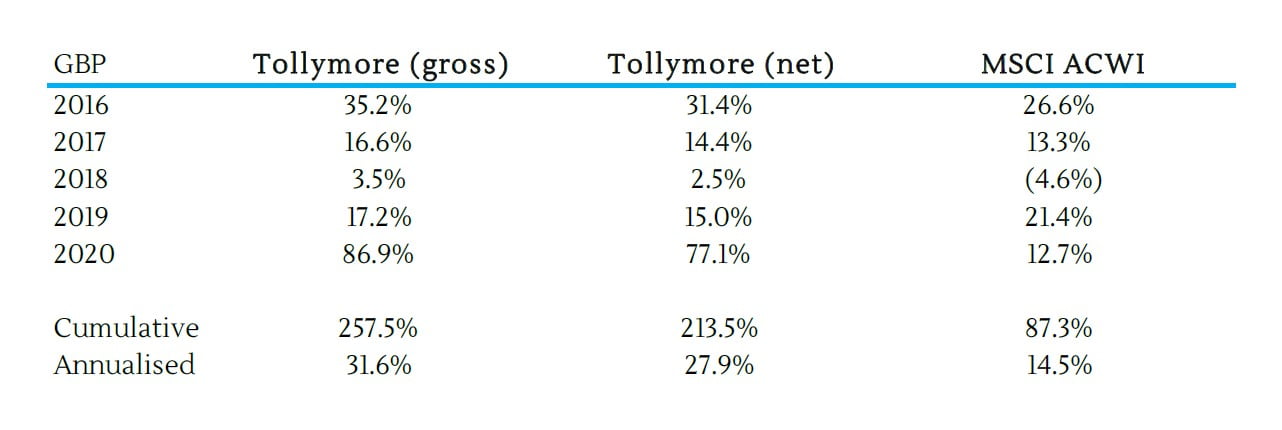

£1 invested in Tollymore at inception was worth £3.58 on 31 December 2020, after expenses but before fees paid to Tollymore. Over the same period £1 invested in the MSCI All Country World Index would have generated a return of 87p. Around three quarters of this benchmark outperformance would have accrued to those invested at inception. Tollymore has generated returns of 28% per annum net of all fees and expenses1.

Operating systems and shortened supply chains

Our investments are a product of a bottom-up organic investment process, and an examination, one by one, of each company’s investment merits. We are deliberately not limiting our investment universe by restricting what we can look at. We do not create rules relating to the business models, economic characteristics or geographic end markets our holdings companies must possess. We have a simple research process requiring our companies to meet high hurdles for business quality as we define it. Having said this, we can make broad observations about the features of the businesses we own. Two features have stood out to us in the context of our preference for businesses with symbiotic value chains2: operating systems and shrinking supply chains.

Value chain symbiosis cannot be achieved while one component’s profits are another component’s losses. Operating systems create value for multiple parts of a value chain. By helping one component, they can simultaneously create value for another. For example, retail operating systems such as Shopify allow sellers to focus on doing what they love – delighting customers by creating amazing products. Everything else, including website design and hosting, payments, inventory management and fulfilment is taken care of through a single counterparty relationship. By levelling the playing field with larger merchants such operating systems allow smaller retailers to access larger markets. Customers benefit from better choice, superior products and lower prices.

There are two limitations of Shopify as an operating system for retail. The first is its lack of B2C brand (which of course is its appeal to brands seeking DTC routes to market) and by extension its inability to help sellers reach the large majority of customers shopping in multi-brand environments. This is both a demand aggregation and a marketing efficiency shortcoming. And the second is its inability to help sellers sell offline, still the mode through which three quarters of commerce is conducted. These limitations inhibit Shopify’s ability to optimise an end-to-end customer experience.

This letter discusses why we think two of our holding companies are uniquely positioned to become operating systems of their respective fields. In so doing we believe they can create vastly more value than they consume via highly compelling supplier and customer propositions. Before we proceed to some detailed case studies of retail operating systems, a brief note on shrinking supply chains. When the value created by a linear supply chain is shared amongst fewer components, win-win outcomes are more achievable. We will discuss shrinking supply chains in our March 2021 letter to partners, with a focus on the conditions under which shortening the supply chain can lead to substantial value creation for owners, suppliers and customers, again using case studies of companies we own as well as those in which we decided not to invest.

The appendix to the letter is a transcript of an interview we did with Good Investing TV, in which we discussed our business quality criteria, investing in companies with emerging moats, the determinants of antifragility within Tollymore, as well the individual investment cases for two of our holdings.

Operating systems: Next plc and Farfetch Ltd

Our most recent investment has quietly but purposefully been building the means to be the operating system of multi-brand, omnichannel retail in the UK and beyond. We acquired an interest in Next plc (NXT:LN) for £66 per share last quarter.

Next is a multi-geography, multi-brand, omnichannel retail business. The company sells own-branded NEXT products, as well as c. 1,000 third party brands via Next’s online aggregation business LABEL, a £500mn business in the UK. Next has 6mn UK online customers and 2mn overseas online customers. Since 2019 Next has also provided customers access to partner brands’ products stocked in those brands’ own warehouses (‘Platform Plus’). This has broadened the range of third-party brands offered. Online sales are routed through Next’s own website and app, as well as brand.com websites. The store network is an important part of the online value chain; half of online orders are collected from Next stores, and 80% of returns are processed through the stores.

Next offers nextpay, a credit facility for UK online customers, and next3step, a credit account which allows customers to spread the cost of orders over three months interest free. Next’s £1bn+ lending book is not just a sales enabler/friction reduction tool but is also highly profitable (60-70% return on equity).

Under ‘Total Platform’ Next makes its warehouses, call centres, distribution networks, customer relationships, marketing engine and lending business available to third party brands, including next day delivery services and store collections and returns. Next also builds and operates brand.com, all in return for a 39% commission on brand partner sales.

Next has a forty-year business history of innovation and successful strategic pivots including pioneering out of town stores when competitors remain focused on the high street, expanding apparel categories from adult wear to children’s clothes and homewares, and expanding beyond own-label online to a multi-brand marketplace, and now becoming the operating system for third party brands via Total Platform. Throughout this period Next has earned consistently high operating margins in the high teens, three to four times higher than high street market leader Marks & Spencer, or online pure plays ASOS and Zalando. One can see how continued progress in widening Next’s SKU variety advantage might drive increasingly attractive basket economics and higher customer loyalty.

The value created by Next over the last fifteen years against a backdrop of the rapid proliferation of ecommerce pure plays, supermarkets’ success in penetrating the UK discount apparel market and declining high street footfall, has been commendable; free cash flow per share has compounded in the mid to high teens. One could have bought the business for £4bn 15 years ago. Since then, Next would have paid the owner roughly that amount in dividends, and today the business could be sold in the public markets for more than double this purchase price.

Distinctively positioned to be the operating system of multi-brand omnichannel retail.

Today, Next is perhaps uniquely positioned to invest in and benefit from delighted customers and suppliers. The strength of the supplier proposition strengthens the consumer proposition and vice versa. This positions Next well to create more value that it consumes.

Online shopping has two characteristics that distinguish it from traditional brick and mortar retailing: (1) product choice: customers can now access products from all over the world, vs. a few physical shopping locations; and (2) convenience: customers can now have goods shipped directly to their door.

We can clearly observe the increases in online penetration of retail sales across the world. But as the retail industry is divided between largely pure play online players, and largely physical retailers, it may be difficult to ascribe relative value to these two propositions. Next is perhaps the only scaled multichannel home and clothing retailer in the UK. The behaviour of its customers is therefore instructive; half of online orders are delivered to Next stores. This might suggest that SKU variety is the most valuable advantage that online shopping has over brick and mortar. But there is another reason: for many, delivery to store is more convenient. In Northern Ireland, delivery is free, yet 28% of orders are still delivered to stores. This would suggest that over half of customers picking up in store are doing so due to convenience rather than cost.

Then there are returns. Rather than attempt to suppress returns rates, Next has embraced the customer’s right to return unwanted items. Again, the stores play an important role in providing an efficient returns process. In some categories of online apparel sales return rates are as high as 50%. And for Next 80% of returns are conducted through stores.

The store network is part of the distribution infrastructure; store stock operates as an online reserve. Stock can be delivered from store to home when there is no warehouse inventory, or stock can be moved from store A to store B for collection by the customer. This omnichannel aspect of the customer proposition may be more defensible than crude subsidised shipping strategies. And the ability to collect in store is more valuable in the context of a multi-brand shopping service – there are not many places in which one can shop across many different stores and pick up once in one convenient location.

Two conclusions might reasonably be drawn from this observation. The first is that online penetration has some way to go before it stabilises, as product choice is a more sustainable advantage vs. offline than home delivery. The second is that retailers with a physical store footprint may, by avoiding the material costs of last mile delivery, be best positioned to offer the most valuable consumer proposition and the most profitable route to market for third party brands.

The supplier proposition is the provision of the most profitable route to market. The internet has lowered the barriers to entry for brands seeking market access by removing the upfront cash commitment associated with retail stores and lowering the operating leverage of such businesses. And e-commerce platforms such as Shopify have reduced these barriers further by turning yet more fixed costs into variable expenses for online brands. But given that 80% of retail shopping takes place in multi-brand environments, brands can access many more customers by trading on aggregation marketplaces such as Next.

Our assumption that the multi-brand omnichannel shopping proposition is valuable is supported by most customers choosing to pick up and return in store and most customers shopping in multiband (online and offline) environments. In addition, many of the world’s most successful pure play ecommerce businesses, such as Amazon, Alibaba, JD.com, Wayfair and Farfetch have been investing in the integration of offline and online shopping experiences.

If we accept this consumer preference for shopping in multi-brand environments, and the sustainable product choice advantage of online, it seems that two categories of sellers will find it hard to generate and retain value for owners. The first is established physical retailers, and the second is brand.com destinations lacking the brand equity required to stand alone and compete for the 20% of consumers shopping in such places.

Next’s traditional business falls in to the first high risk category: a high street retailer with burdensome fixed cash obligations such as operating leases and wages. Next’s investments in next.co.uk over the last 20 years are evidence of customer-centricity. But its more recent efforts to help competing brands increase their addressable markets and safeguard their own businesses against the more level playing field in an online world seem to be particularly forward looking. And necessary. Since 2014 Next has featured third party brands alongside its own Next and Lipsy brands through its online platform LABEL. The first order implication of this move has been to increase competition with, and potentially cannibalise sales of, Next’s higher margin own brands.

But in the words of CEO Simon Wolfson “There is nowhere to hide on the internet, one way or another our customers will find the brands they want. If they can find what they want on our website they are more likely to come back to us, furthering our ambition to be our customers’ first choice for clothing and homeware online.”

Since the introduction of Platform Plus two years ago, the number of third-party brands available on the Next platform has doubled to 1,000, and Next’s active online customer growth has accelerated from mid to high single digit rates to mid-twenties in calendar 2019 and 2020, despite the larger base. More recently, visits to next.co.uk have more than trebled since the first lockdown in the UK at the end of March 2020. This is the highest growth rate amongst established ecommerce peers such as H&M, Zara and Asos.

LABEL was originally a wholesale business model, but today more than half of this business is done on a commission basis. This may increase as the rate of growth of brands paying a take rate is three time those selling wholesale. LABEL represents just c. 13% of total Next sales currently.

In return for a flat all-inclusive 39% take rate brands receive the following benefits: 8mn active customers, growing c. 25% pa.; price control – Next is a full price retailer – 15% of sales are on markdown, vs. the industry average of 35-40%; Next day delivery network including returns and collections from stores; and a large-scale consumer lending proposition.

The timing of LABEL’s quiet but notable business progress is fortuitous; it positions Next to gain from the COVID lockdown-induced restructuring of the UK apparel industry. Cross-shop between Next and retailers in company voluntary arrangements or administration such as Debenhams and Arcadia Group is high. These retailers represent a tenth of UK market capacity, vs. Next at c.7%, including LABEL.

In addition to the omnichannel distribution advantage, but much more nascent, is the opportunity to use online information about consumer shopping habits and preferences to optimise in store inventory and customer service. In store collection and returns also drives footfall and therefore incremental selling opportunities.

Avenues for highly accretive internal reinvestment

The economics of online capacity growth are attractive. The current book value of Next’s online warehouse and distribution plant and machinery assets carries annual depreciation of c. £20mn, 1% of online sales. Next is halfway through a six-year warehouse and logistics investment programme costing £300mn; this will increase annual online sales capacity by £1.7bn. So, 18p of investment is increasing annual sales capacity by £1. And the principal growth driver of online, the LABEL aggregation business, carries no inventory and enjoys negative working capital.

Next’s multi-brand offering is exploiting historic distribution and marketing investments. Next is leveraging existing assets to expand into close adjacencies. And as the scale of the business increases, so too does the utility and value of Next Unlimited, which offers unlimited free home delivery to customers for £20 per year.

The LABEL penetration opportunity is vast. LABEL sales still represent just 1% of the UK apparel market, vs. 6% for the NEXT brand alone. Sales per LABEL brand are also still less than £1mn pa. Given the strength of the LABEL proposition in a world in which consumers overwhelmingly prefer to shop in multi-brand environments, engines of business growth may include adding more brands, the expansion of product ranges for each brand that are available on LABEL, and extensions into adjacent categories such as Beauty and Home. LABEL still sells mostly apparel; home and beauty together are just 15% of revenues. The online penetration of beauty products is still less than 10% in the UK, but the high value, small size and low returns rate of beauty products make them well suited for online sales. Homeware online penetration is c. 15%, around half of the proportion of apparel and footwear sold online.

Manufacturing is a nascent growth opportunity. Retail operating systems can further integrate themselves into retail value chains by reorganising their partners’ supply chains; that is, by connecting merchants with manufacturers. Next sees an opportunity to leverage its sourcing experience to create and distribute partner brands’ products. In 2020 it signed such licencing agreements with Ted Baker, Oasis, Joules and Scion Living. These opportunities, and the economic terms underpinning them, may only improve for Next given the COVID-induced failures of large retailers.

Online business models enable geographic expansion. As rent is replaced with digital marketing dollars, Next’s online assets have allowed the company to profitably enter new regions, unencumbered by the customer density required to economically justify physical store investments. Online sales of c. £600mn are growing 25%+ pa as Next adds >1mn new overseas customers per year. NEXT brand accounts for c. 85% of overseas revenue and has been growing 20% pa. However, after initially modest take up, LABEL brands have started to exhibit meaningful growth, +c. 70% yoy as the range of brands has increased substantially.

This overseas growth is valuable. Digital marketing spend has been doubling annually, with sound return on investment; the business is generating £1.53 in incremental orders within the first year for every £1 spent on digital marketing. Assuming a 40% gross profit margin implies a 20-month gross profit payback on each £1 spent on marketing. Overseas customers spend 20% more each year on average; a customer spending £100 in year one spends >£350 p.a. in year seven. Despite the attractive unit economics on digital marketing initiatives, almost 90% of new customers are still acquired organically.

Total Platform is the most nascent, and potentially most valuable opportunity. The LABEL leadership team is responsible for developing client relationships for Total Platform, leveraging pre-existing relationships with LABEL partners. Next’s first Total Platform customer was Childsplay Clothing, which sells luxury childrenswear. While www.childsplayclothing.co.uk looks like an independent brand, part of the Total Platform proposition is to reduce friction of signing up to a new website. Next account owners can sign in using their Next login credentials and Next credit customers can pay using nextpay.

Next’s CEO summarised his thoughts on the prospects for Total Platform as follows:

“Total Platform is potentially a very exciting business because what it does is it takes a partner brand and it allows them to plug in to 20 years' worth of investment that NEXT has made in its web systems, its marketing, its online warehousing, its distribution, whether that distribution be through couriers, through NEXT stores, through overseas networks, it plugs them into our call centres and gives them our credit offer. And that integration allows them to have a much more powerful and robust presence both in terms of U.K. online presence, their online presence overseas where they can tap into all the work that we have done to develop 70 different international websites for our business. We can put their product into those countries on websites that are translated, that deal in local currency and it takes specialist forms of local tender types, for example, cash on delivery in Russia.

They also have the advantage, if they want it, of being able to deliver their stock through our stores. We know that 50% of our orders are picked up in our stores. So, we think, the use of NEXT stores as a post office is actually a very powerful marketing tool, even more powerful as an easy way to return stock.”

Next’s brand aggregation business LABEL has made this possible. Next has been delivering LABEL stock from hundreds of third-party brands into its own warehouse for six years. To integrate that stock into Next’s system, it is given a single unique identifier. This identifier allows Next to know who bought returned items and how they bought them so that customers can be refunded accurately, regardless of whether returned online or in a Next or brand partner store. Contrast the alternative available to brand.com seeking to grow sales profitability via outsourcing aspects of the value chain independently. A new website built from scratch needs to be integrated into the seller’s warehouses, credit systems, customer account systems and call centres.

The cornerstone of the Total Platform proposition is the reduction of business risk facilitated by swapping fixed costs for a single commission structure. A commission structure which aligns the interests of Next and the partner brand. 2020, perhaps more than any year in recent history, may have brought the benefits of such a cost structure into sharp focus for retailers mandated to shut their doors all over the globe. And even in times of rapid growth, Total Platform eliminates the growing pains of step-ups in fixed costs and major capital investment projects to expand capacity and customer support. In this way Next’s vertical integration can lower partner brands’ capital intensity. The utility of business resilience is particularly high in the volatile fashion industry.

AS Next scales this business, the proposition becomes increasingly compelling due to the size difference between Next and the partner brands. A 50% step change in call centre or warehouse capacity for a partner brand might be achieved by a mere 1% increase in Next’s volumes. In addition, Next’s longstanding reputation, physical high street presence and high customer satisfaction may serve to lower Next’s costs of customer acquisition and retention vs. third party brand partners, particularly smaller and emerging brands for whom Next’s Total Platform proposition may be especially compelling. It also allows newer and emerging brands to focus on what they find interesting – designing and creating great products, and delighting customers, rather than the unseen, but crucial, components of a retail supply chain, such as data security, call centres or warehousing.

Capital will be increasingly directed to servicing online demand. Management forecasts modestly lower capex over the next five years vs. the previous five. But warehouse and systems capital requirements are set to rise dramatically with store capex falling to levels commensurate with maintaining, rather than expanding, the store estate.

So, what kind of returns can these internal investments generate? 18p of capacity investment is increasing annual sales capacity by £1, and the operating margin on online business is running at c. 18%. Incremental returns of c. 100% are attractive indeed. Of course, this fully loads the operating expense base into the new profit pools generated from these investments. If we use the group gross margin of 40%, incremental returns are north of 200%. Achievable rates are likely between these two percentages; the point is that incremental returns are very high, and capital can be reinvested at substantially above opportunity cost levels. Next currently earns returns on non-lending capital employed of more than 100%.

As for increasing the lending book, this too is valuable. Next uses group borrowings which cost 3-4% to lend to customers at a rate of 24%. Next generates almost £300mn in revenue pa from its £1.2bn lending book. Assuming its current 85% debt funding mix, it earns c. 70% RoEs in this business. The low cost of servicing this business is due to that fact that it serves existing retail customers, three quarters of whom have been shopping with Next for more than five years.

Now for the bad news. We hope the priorities for the use of cash in this business will change. For 15 years Next has been repurchasing shares and issuing special dividends due to a limitation on the amount of capital that can be internally deployed into value accretive projects. Today, Next can use that capital to help smaller, more capital constrained brands with a higher funding cost, and in so doing become the operating system of multi-brand, omnichannel retail. For many publicly quoted UK businesses, capital allocation agendas are set by a low-quality institutional investor base requiring sustained annual dividends to satisfy their marketing-led investment remits.

Prior to 2019, Next’s preference for returning excess cash to shareholders was a result of its inability to deploy capital profitably in overseas markets. But two years ago, that changed. The company is getting better at targeting those customers who will like Next’s clothes. And Next has found distribution partners capable of delivering high quality service at attractive unit economics. The result is that from 2019 Next has been earning supernormal incremental returns on investments in these areas; c.100% IRR for UK digital marketing campaigns and almost 400% for Overseas campaigns. Extraordinary circumstances such as these provide the perfect opportunity to reset the capital allocation agenda and really lean into the online opportunity that few others are so well positioned to exploit.

Scale is a more important driver of success in online vs. offline business models, especially for working capital light marketplace models. Scale drives advertising efficiencies: large scale, reputable retailers will win Google and Facebook auctions with lower bids due to better quality scores – that is, high customer satisfaction and strong brands increase click through rates. Scale also lowers shipping costs via volume discounts on last mile delivery. Scale begets scale; this is responsible for the winner take most market structures of most online categories.

Unfortunately comments from management such as “We recognise the importance of providing our shareholders with consistent and reliable dividend returns” and “We remain committed to paying dividends to our shareholders once the crisis has passed and do not anticipate any long-term change to our dividend policy” may mean that catering the existing shareholder register inhibits total EVA that can be generated by the company over the long term.

Given highly able management and the huge optionality embedded in this business; that is, the opportunity to become the operating system of multi brand, omnichannel retail, why pay dividends and buy back shares? The IRR on these activities is likely to be low compared to internal business investments that could lead to quite extraordinary industry dominance. This may be particularly true at this juncture, in such a period of competitor distress and disarray.

See for example the considerable business progress of Farfetch, progress that accelerated in moments of maximum stress, such as 2009 and 2020. That company’s capital allocation agenda is designed to widen a set of unfair business advantages so that their assets become increasingly hard to replicate. It is this type of anti-fragility that we see with Next. A company whose competitive position has been strengthened by COVID-induced retail business failures and accelerated online shopping habits.

Perhaps we have misappraised this opportunity. Or perhaps capital allocation choices at Next are governed by factors other than simply long-term business value compounding. Presupposing directionally right analysis of Next’s opportunities for value accretive investments, capital returns to shareholders could diminish the value of optionality embedded in Next’s equity price. Dividends are typically paid by businesses caught on the wrong side of time. Next could be a special business for the future.

Next’s market cap was £8.5bn when we acquired our interest; the quoted value of the enterprise including finance receivables was £9.5bn, vs. FY20 EBITDA of £1.1bn, or 8.5x EV/EBITDA. In FY20 Next generated £6 in FCF per share; we paid a 9% yield for our shares. Of the c. £800mn Next generates in FCF, around £130-140mn is spent on sales and marketing. We estimate Next comfortably generates more than £1bn p.a. in pre-tax owner earnings, a 12% yield to current price available to equity owners.

This valuation, which anticipates no growth or value neutral reinvestments, together with Next’s outstanding track record of economic progression and shareholder value creation amidst a challenged industry backdrop, mitigate against substantial loss of capital for equity owners. Meanwhile Next may be uniquely placed to leverage existing assets to exploit optionality and become the operating system of multichannel omnichannel apparel, beauty and homeware. And to do so on terms that are extremely valuable to owners, customers and sellers alike.

One of Tollymore’s largest holdings, Farfetch (FTCH), is a global luxury digital marketplace for brands, retailers, and consumers. The marketplace connects 2.5mn active consumers in 200 countries to 1.3k sellers across 50 countries, including 500 direct brand e-concessions. FTCH is the biggest online destination for luxury in the world.

The consumer proposition is predominantly range of merchandise and curation of supply. But also localised websites, multilingual customer support and same day delivery in 18 major cities. Accessibility to global products is evidenced by consistently >90% of transactions being cross-border. Shopping for luxury products via FTCH’s website or app enables customers to search by designer, category or keyword, is available in multiple languages and accepts multiple payment methods.

80% of products sold online are in a multi-brand environment. This is evident in brands’ historic willingness to have e-concessions in department stores – that is where the footfall is. But the value of a fashion marketplace goes beyond choice. As a marketplace, rather than an inventory-owning retailer, FTCH can better curate products for consumers. FTCH can more rapidly test and iterate messaging, content and SKUs; purchasing inventory would slow this down. A large SKU count also makes it easier to satisfy consumers’ desire for ‘newness’ via daily product additions and the ability to offer new/more extravagant products without inventory risk.

A compelling supplier proposition seems to be evidenced by: the large number and strong growth of brands and boutiques on the platform; that 98% of retailers have done so exclusively; and FTCH has retained all top 100 retailers and all but one top 100 brands over the last five years despite strong supply growth.

What are the reasons for this? Access to 2.5mn customers across the globe, on a fully managed basis; that is, everything from content creation to last mile delivery. An online offering helps brands reach new audiences, increase visibility, and expand their presence into new geographical locations without the need to invest in retail infrastructure.

The price for this is a 30% take rate to FTCH. This is high by the standards of marketplace business models. But it seems to economically be a better deal for brands, no longer required to pay the retailer margin. Under traditional linear industry economics, a product costing $20 may sell for $100. The retailer typically keeps most of the $80 mark-up, perhaps around two thirds of it. The brand margin is therefore c. 25%. For a brand selling directly on FTCH, this might double to 50%, what is left after the product cost and FTCH’s 30% take rate are deducted from the retail price. Brands can achieve incremental sales by making their inventory available to a global luxury audience without increasing their invested capital or diminishing their returns on capital.

Brands have full control over visual representation and pricing. FTCH allows access to a targeted luxury customer base, mitigating potential concerns around brand dilution. Increasingly FTCH is overcoming challenges faced by emerging brands such as brand exposure and limited reach.

FTCH’s marketplace offers a place alongside leading luxury brands, lending credibility to the emerging brand and providing access to luxury consumers, who, in turn, are attracted by the opportunity to discover under-the-radar, exclusive, emerging brands. This potential flywheel has opened because of FTCH’s purchase of New Guards Group, a brand incubator. The market reacted to this acquisition by cutting the stock in half, a price decline that piqued our initial interest. The NGG acquisition helps FTCH to provide more choice, including exclusive products from emerging brands. That is, to drive engagement through limited supply.

Like Next plc, Farfetch is embracing the omnichannel advantage. But unlike Next, FTCH’s distribution is largely decentralised and offline sales are made via partners’ stores. FTCH has c. $5bn of inventory available to its customers, which has two channels. For the online channel FTCH represents most online sales for sellers. There is also a compelling offline advantage to being on the FTCH platform: you become a distribution partner. That is, FTCH will distribute through those fashion boutiques that are on their platform, sending footfall into the stores, creating offline selling opportunities not available to non-FTCH partners.

Customer orders are directed to a boutique based on proximity, cost of delivery and fulfilment record. This model is scaling successfully due to the absence of strong local incumbents. FTCH has not needed to build supply and demand in each market; the distributed model arises from the value of SKU range. It is also resilient: 85% of SKUs are available from multiple sellers within FTCH’s supplier network. FTCH can therefore tap supply from wherever it is. However, it is more expensive than centralised logistics, in which multiple items ordered on the FTCH website arrive in one box when processed through a Fulfilment by Farfetch facility. FTCH has six Fulfilment by Farfetch warehouses, which are 3PL and therefore have no associated capex obligation. The main 10-20% of SKUs are available in these centralised warehouses.

The high take rate is supported by high gross profit products and a fragmented supply base characterised by family-controlled companies seeking to protect brand integrity. In addition, there are some more subtle characteristics of the luxury fashion industry that may be creating special unit economics. Typically, ecommerce marketplaces grow scale and compete partly on price. This is not how to build a sustainable ecosystem in the luxury industry, in which decisions are a function of emotion, personal identity and scarcity. This translates to a $600 AOV, a 30% take rate, and mature cohorts delivering > $100 per order contribution/55% order contribution margin. LTV to CAC payback of fewer than six months makes investing to grow the active customer base by 50% each year the right capital allocation choice. Finding luxury customers is a costly endeavour, but when they are found there is an immediate payback on CAC. FTCH has run promotions in the past, but today seems to be increasingly focused on increasing the loyalty and therefore value of the customer base and allowing the brand full control over price setting. This seems consistent with sustainable value creation vs. ephemeral but expensive revenue support.

Is this a symbiotic value chain? That is, is there a non-zero-sumness to the sharing of value creation in which suppliers, customers and owners enjoy win-win-win dynamics? It is not immediately obvious FTCH passes this test. The superior economics of FTCH to brands may result in pressure to disintermediate boutiques. There seems to be a clearly compelling proposition for brands and consumers, but the proposition for retailers seems to be less clear. In particular, the margin that needs to be surrendered (and ceded to brands) by being on FTCH’s platform vs. the traditional linear industry model. In return for this margin dilution the retailer receives a range of valuable services such as access to a global luxury audience (which also increases the probability of full price sell through), data insights, logistics, outsourced customer service, and the omnichannel offline footfall described earlier. But given the opportunity for the brand to disintermediate the boutique and take all the margin, why would a retailer happily sign up for this, and what sustains their future in the value chain under a marketplace model?

More brands seem to be bypassing retail partners and exploring a direct-to-consumer model. The reasons: larger profit margins and stronger customer relationships/insight. Brands have increased in FTCH’s mix, now 50:50, a trend which management expects to continue.

One aspect of value chain symbiosis is FTCH’s supply chain capabilities provided to platform partners, such as content creation and global fulfilment, integrating global logistics partners in a single interface. Thus, as with Next plc, there are interesting comparisons to both Amazon and Shopify here.

The following anecdote, from Frederic Court of Felix Capital, FTCH’s earliest VC investors, suggests the presence of a non-zero-sum value chain:

“I am often asked for anecdotes about Farfetch and the story so far, there are many special moments but here is one that resonated particularly strongly when it happened, at one of the company’s “Gatherings”. José had pioneered the event early in the life of the company, to cement the relationship with our key partners, and create a stronger sense of community, gathering all the boutique owners and brands to Porto or London, once or twice a year for a couple of days (hundreds of people connecting). This was a great opportunity to meet many boutiques and brand owners, to explain the development of the Farfetch platform, and get feedback from users. A couple of years into the investment, one of the first boutique owners to have worked with Farfetch (and still a partner to this date) came to me at a Gathering and said: “thank you, for investing in Farfetch and saving my store”. Without Farfetch his store would have closed because of the recession and he was grateful that we had funded Farfetch, which ended up rescuing his business from the recession. This was an emotional moment illustrating how critical the platform had been for many boutiques at difficult times, reinforcing the mission of the company, and all its stakeholders, to connect fashion lovers and make those products more accessible”.

Unfair advantages are numerous and growing.

Network effects are two sided and global. More brands and boutiques on the marketplace increase the choices available to consumers, and more consumers increases the potential sales for sellers. The network effects are global. That is, the total global SKU variety is a factor in the consumer proposition, and the total luxury consumer base is a relevant factor in determining value to a seller. This makes these global network effects more difficult for entrants to overcome via clustering strategies. Consumers prefer to shop in a multi-brand environment, and FTCH offers more brands to consumers than any other luxury destination. In addition, the economics of distributing via FTCH are more appealing to brands than retail, which typically will take half of the retail price as a gross profit, vs. FTCH’s 30% take rate. Finally, they retain control over how their products are presented and priced with FTCH vs. a multi-brand retailer. The appeal of control is particularly strong in luxury because in times of depressed cyclical demand, retailers will seek to unload stock via discounting which erodes luxury brand value. Luxury brands therefore seeking to complement their brand.com presence with a multi-brand channel find FTCH to be the most appealing option. As more brands make this choice FTCH’s multi-brand proposition strengthens. Recent evidence supports the notion that this advantage is widening: FTCH’s top 10 brands, which includes Gucci, Prada and Fendi, have more than doubled their direct stock on FTCH yoy. And on the demand side active customers are increasing >50% yoy.

Fragmented supply increases value of a marketplace: 19 of the 20 largest luxury fashion brands by revenue are in Europe yet address global demand. Large brands access demand by building expansive networks of directly operated stores and through department stores. Emerging brands typically have no route to the global market. They rely on wholesale distribution through a network of independent fashion boutiques. As a result, luxury fashion inventory, from both larger and smaller brands, is distributed across a highly fragmented network of luxury sellers. FTCH has c. $5bn of third-party inventory (not owned but available for sale) sitting in thousands of stores across the >50 countries from which supply is sourced, leading to multiple combinations of shipping routes and logistics providers. The e-concession model means that the same warehouses that serve brand.com serve FTCH. This happens with 500 concessions and FTCH taps directly into the brand’s inventory without acquiring it. Thus, some of the acceleration in revenue that FTCH has recently experienced was a result of these brands prioritising their direct-to-consumer sales.

Established partner relationships are hard to dislodge. In seeking to preserve brand integrity, luxury brands have historically been reluctant to partner with an online retailer. FTCH has developed relationships with the leading luxury families to overcome this reluctance by, for example, allowing control over visual representation and pricing. As a result, these brands have agreed to partner with FTCH on an exclusive basis – 80% of items listed are exclusive to FTCH – and FTCH has 8x the number of SKUs of its nearest competitor. It is now likely much more difficult for a new entrant prise these relationships away.

FTCH is the only scaled luxury marketplace. However, it faces competition from technology companies enabling ecommerce e.g. Shopify; online luxury retailers which hold inventory and ship from centralised warehouses, such as YNAP.com; and multichannel retailers. Richemont, the owner of YNAP, removed YNAP founder and CEO Federico Marchetti in March 2020 amidst reported frustration in YNAP’s lack of profits. With seeming competitive disarray, FTCH continues to invest ever increasing dollars at widening its business model advantage.

There is another subtle but significant advantage of marketplace over retail: FTCH’s marketplace model confers an important and widening advantage vs. linear retail peers. FTCH’s technology is integrated with the stockpiles of its sellers. FTCH therefore has access to data from traffic and sales not only made through the FTCH platform, but also offline in its boutique and brand partners’ stores. This information can be used to make FTCH’s services more valuable to more engaged consumers, but also to provide aggregated feedback to sellers.

Like Next, Farfetch is investing in further integrating itself into the luxury value chain through Farfetch Platform Solutions (FPS), a white label ecommerce offering. On the front end, FPS creates global websites, apps or WeChat stores. Back end services allow retailers and brands to synchronize their websites with in-store and warehouse inventory, both from mono-brand stores and other suppliers in their distribution network and facilitate in-store pick-up and consumer returns. Layered on top are services such as marketing, localisation, production and warehousing. These white label solutions are being provided for Harrods in the UK and 20 other clients.

Also like Next, FTCH is demonstrating anti-fragile business qualities. FTCH’s boutique suppliers have faced mandated retail store closures due to COVID 19 restrictions, and have suffered from a material decline in tourists, particularly from China. FTCH’s revenue growth accelerated in 2Q20 as these boutique partners sought to access luxury fashion consumers across the globe. COVID has helped to increase demand too: FTCH saw a spike in app downloads in the first quarter, especially in China in which app downloads more than doubled yoy. Chinese consumers represent more than one third of luxury consumption, of which typically 70% is made while traveling. That is $70 bn of personal luxury goods purchased by Chinese nationals while traveling outside Mainland China. Demand, which, with all else being equal, seems to have been repatriated online with huge drops in international travel in 2020. Likewise, FTCH’s FPS customers, such as Harrods, were able to continue serving customers during lockdowns.

Expect high reinvestment rates and incremental returns.

FTCH has a large, growing addressable market driven by online penetration, opportunities to carry adjacent products, exceptional unit economics and evidence of operating leverage.

Luxury fashion transactions are increasingly online. Over the last decade online penetration of luxury sales was c. 2% and has grown 20-25% pa. According to Bain online now accounts for 12% of the global $330bn luxury sales market, with customers increasingly influenced and enabled by digital channels, including in their physical purchases. 75% of luxury transactions were influenced by the online channel, and almost a quarter of purchases were digitally enabled. Bain expects online to become the number one channel with 28-30% market share by 2025.

Bain expects the global luxury market to be worth >€350bn by 2025, driven by growth in Chinese consumers, online channel and consumers younger than 45. This might imply a >$30bn online commission pool, c. 85x FTCH’s revenues. FTCH’s current share of the global market for personal luxury goods is c. 0.3% of the estimated total addressable market.

FTCH has the right model for industry domination. FTCH does not compete with any other large luxury marketplace. Its competitors are online brand ecommerce, omnichannel multi-brand stores and online multi-brand retailers. Jose Neves is playing for winner take all: “I believe a single company will orchestrate this revolution in the conversion of offline and online luxury retail because, even if multiple retail-tech vendors emerge, the new technology will have to be adopted both by retailers and consumers. We believe consumers will always gravitate to one single app, forcing vendors to gravitate to one single platform, most likely a platform that has already built consumer-side critical mass and benefits the entire ecosystem. This all translates into a potential $450 billion addressable market for Farfetch, which, as the operating system for luxury, we want to transform, empowering individuality for consumers, curators and creators of fashion.”

Despite a clear understanding of FTCH’s advantages, attractive unit economics and long runway for demand generation investments, management does not have a ‘growth at all costs’ mindset. Jose and Jordan have frequently reiterated their focus on protecting margins and strongly growing the profitability of the business, which they expect to be EBITDA break even this year. So far, the demonstrable operating leverage in the business lends credibility to these ideals.

Despite more than quadrupling in value since we originally acquired shares at $14, the rates of returns we expect to earn on our ownership remain high. An estimated $500mn of owner earnings are being invested into demand generation efforts that are yielding materials ROIs. Assuming a three-year customer lifetime and one order per year would imply incremental returns north of 30% and an IRR on the equity of $20bn north of 20%. Assuming a five-year customer lifetime and one order per year would imply incremental returns north of 50% and an IRR on the equity of around 40%.

The quoted price remains inconsistent with the deep reality. FTCH has a large and growing addressable market, a differentiated business model, high barriers to profitable participation, a win-win value chain, great unit economics and a capable, aligned leader.

Thank you for your partnership,

With my best wishes.

Mark

Read the full letter here.