This quarter will be a critical period in the Brexit process. More than two years on from the June 2016 referendum, the terms of the United Kingdom’s exit from the European Union remain undecided and the final outcome could still go in a number of different directions. But over the next few months, investors should gain a clearer sense of how the planned separation is to proceed and whether the worst-case near-term scenarios can be avoided.

March 29, 2019, remains the official date of the formal exit, but before this can happen both sides will need to come to an agreement on the terms of withdrawal and pass it through their respective parliaments. Failure to do so risks an abrupt departure for the U.K., with tariffs and non-tariff barriers on all goods and services trade between the two markets reverting to World Trade Organization (WTO) levels. For the U.K. economy and markets in particular, this would likely prove highly destabilizing. And even if an agreement on withdrawal can be reached and signed into law by March (avoiding a so-called hard Brexit), the details of the future trading relationship will still have to be determined. This is a further process that could take many more months, or even years, to complete.

[REITs]Q2 hedge fund letters, conference, scoops etc

A number of key dates will bear close watching (Exhibit 1). The next European Council meeting on October 18–19 had long been targeted for an agreement, but expectations have now shifted to a special meeting likely to be called for the week of November 12. If the Theresa May government and the European Council can reach a deal on this date, both the U.K. and the EU will then move to hold parliamentary votes to sign it into law.

The U.K. has imposed a vote deadline of January 21, 2019, and were a withdrawal agreement not to be passed by this date, the government would have to present parliament with an alternative way forward. If the U.K. does leave with a deal in March, attention will then turn to December 31, 2020, the end of a proposed 21-month transition period during which the details of the future U.K.-EU relationship would be set out. Little would change during this period. British members would no longer sit in the European Parliament and vote on EU legislation, but the U.K. would retain the other rights and obligations of EU membership, crucially including zero-tariff access to the EU single market. There are no guarantees that a favorable trading relationship could be established even by the end of 2020, but the transition phase would at least reduce near-term uncertainty for investors.

Terms of Separation

At the heart of any agreed withdrawal plan will be the status of the Irish border. This is the last of the three divorce questions to be resolved alongside the U.K. exit payment to remaining EU member countries and the rights of non-citizen residents on each side. In the event that the U.K. finally leaves the EU single market and/or customs union after 2020, product checks would have to be enforced on the sole U.K.-EU land border between Northern Ireland and the Republic. Both U.K. and EU leaders are in agreement that a hard Irish border is unacceptable, but their preferred solutions to the problem differ. The approach taken by the plan the U.K. government is currently expected to table at the November EU Council meeting makes two main proposals: common regulations for goods traded between the U.K. and the EU, as well as a special customs partnership in which EU tariffs and trade rules would apply to all goods that enter the U.K. bound for the EU. But in its current form, this deal is unlikely to be accepted by either parliament. Hard Brexit supporters in the ruling U.K. Conservative party oppose the plan for staying too closely aligned with EU rules, making for a low likelihood of majority support. European lawmakers meanwhile may oppose the deal for circumventing EU rules— ending the free movement of people between the U.K. and the EU, while effectively retaining access to the single market, and potentially opening the door for other countries to do the same.

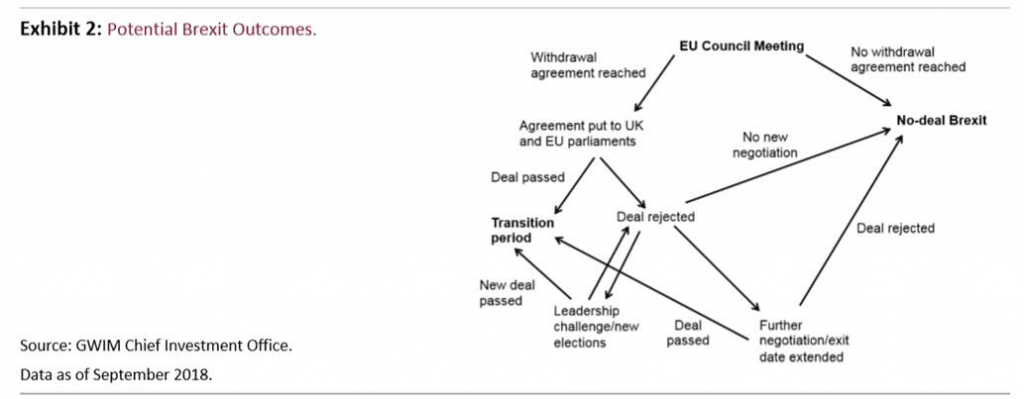

Whether a withdrawal agreement can be reached and passed into law in time for the March exit date therefore remains to be seen, but the next few months should give investors further clarity. If a deal fails to pass either parliament, any one of a range of possible outcomes could follow (Exhibit 2). A no-deal Brexit would be the default result assuming no alternative plan of action were to be agreed. The official March exit date could also be extended in order to allow time for further negotiation—a measure that would require unanimous approval from the other 27 EU member countries. Or the U.K. government could be subject to a confidence vote, potentially leading to a change in leadership, new elections, a new withdrawal proposal and possibly even a second referendum.

What Might This Mean for Investors

The prospect of a no-deal Brexit and the return of WTO tariffs, non-tariff barriers and customs controls remains the biggest concern for markets at present. For the U.K., this would likely mean not only reduced goods and services trade with its biggest partner, but also a loss of export-oriented foreign direct investment and higher business uncertainty. The pound would likely depreciate and the Bank of England could be forced to reverse course on monetary policy normalization. The impact would be reduced with an agreement and transition outcome, though non-tariff barriers on service trade (which are not avoided under the current plan) would still represent a headwind for U.K. growth.

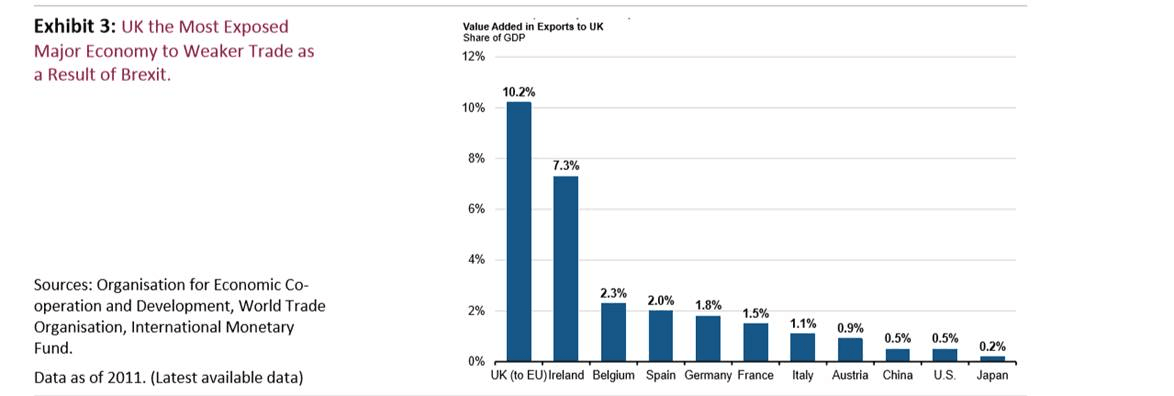

But with or without a transition deal, Brexit does not pose the same systemic risks to global markets as the euro crisis, and the most damaging effects of a no-deal scenario should remain confined to the U.K. itself. Prominent estimates for the cumulative loss of output for the U.K. economy out to 2030 range from 2.2% (Open Europe) to 7.7% ((Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development) OECD) in a worst-case outcome. The EU would be the most exposed of the major economies through weaker exports to its second-largest member, though as a share of its economy the impact would be lower than for the U.K. Indeed, some individual European markets could be potential beneficiaries from a no-deal Brexit given plans announced by a range of financial services firms, automakers and aircraft manufacturers to move European operations onto the mainland to retain unrestricted access to the single market. And for other large trading partners around the world, exposure through weaker exports to the U.K. would be lower still (Exhibit 3). The Brexit referendum result of 2016 was a major geopolitical shock for the world, but the global economic fallout from the U.K.’s final exit is likely to be more muted.