Key Takeaways

- Climate change and biodiversity loss are interlinked, but solutions to reduce greenhouse gas emissions are unlikely to benefit biodiversity in the same way.

Q1 2021 hedge fund letters, conferences and more

- Instead, biodiversity needs to be given equal consideration in any nature-based climate solution offering.

- The biodiversity crisis is a still-nascent ESG consideration for investors but it is climbing up the agenda.

- Governments and companies are increasingly viewing the incorporation of natural capital into assessments of wealth and performance as fundamental to addressing biodiversity loss.

- Targeted corporate and government actions to reduce deforestation linked to soy, beef, and palm oil will form a key part of the response, as will supporting smallholder farmers and indigenous communities to protect nature.

Biodiversity Loss: Where Do We Stand?

Biodiversity loss is a global phenomenon. The recent Intergovernmental Science-Policy Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services estimates that of the eight million plant and animal species on earth (75% of which are insects), around one million are threatened with extinction. In the U.S. and Canada, bird numbers have declined by a third since 1970, with even the most abundant species, like starlings, seeing a 49% decline over the same period. The Yangtze River dolphin, last seen in the early 2000s, is thought to be the first dolphin species to be driven to extinction by humans. And Australia's regent honeyeater is also now facing extinction because declining numbers are inhibiting the males' ability to learn their courting song.

Nature is evidently suffering, but what can governments and corporations do to reverse these alarming trends? The first step is to acknowledge the implications of the destruction of nature. Increasingly, biodiversity loss driven by habitat degradation and climate change, as well as by the introduction of invasive species and other anthropogenically-induced factors, is being recognized as a systemic risk with far-reaching consequences. The World Economic Forum estimates that more than half the world's GDP, or $44 trillion, is moderately or highly dependent on nature and its services. With such a dependence on nature, why are we systematically destroying it? The question is perhaps best answered with another: what is driving the biodiversity decline?

The answer, on land at least, is relatively simple. Terrestrial biodiversity loss is tied to three consumer staples: palm oil, beef, and soy. These soft commodities are responsible for around 70%-80% of the 10 million hectares of natural habitat that the UN Food and Agriculture Organization estimates is lost to deforestation globally each year. We have identified four key ways companies can help arrest deforestation (see infographic and palm oil section below). Marine biodiversity is also suffering, with shark and ray populations declining by 71% since 1970, driven by an 18-fold increase in fishing pressure, meaning that extinction is now a near-term risk. Such is the complexity of nature that the loss of a top-level predator from our oceans could have other far-reaching and unforeseen effects.

Indeed, with the COVID-19 pandemic we are experiencing how an invisible shift in nature can manifest as a global socioeconomic crisis. Many are beginning to note the connection between habitat or biodiversity loss and the growing risk of emerging infectious diseases, especially zoonoses (70% of emerging infectious diseases), upending society.

As this crisis has shown, the health of nature can determine our own wellbeing. However, despite this understanding, actions to stem biodiversity loss are not entirely obvious--as we see when we look at corporations' responses.

Nature's Complexity Obscures Its Financial Materiality

Business and finance may have a key role in stopping the destruction of nature. Though some corporations are proactively addressing the nature-related financial risks that stem from biodiversity loss--such as disruption to supply chains or volatility in raw material prices--many more are unaware of such risks. The more complex and less palpable issues to which they are financially exposed--given their reliance on fragile, interconnected ecosystems--are especially underappreciated. Indeed, there is a historical disconnect between investee companies addressing nature loss and the questions investors are asking. This disconnect has been exacerbated by a lack of transparency and disclosure of nature-based metrics in companies' financial reporting. The heterogeneity of biodiversity (the World Wildlife Fund records 867 distinct terrestrial assemblages of species and communities across the world) and its nascent status as an ESG concern, makes it difficult to aggregate biodiversity data at the enterprise level and to achieve consensus on relevant biodiversity metrics for companies.

Furthermore, though biodiversity is creeping up the agenda, climate change still dominates. Taking Larry Fink's latest letter to CEOs as an example, "climate change" features about 27 times while he does not mention "natural capital" or "biodiversity" at all. Perhaps it is the complexity of biodiversity, or confusion about what biodiversity and natural capital are, that is causing this rift. Or maybe it is the current absence of direct and material financial ties to nature that explains why investors are not making ecosystems a focal point of their ESG analysis.

Nature-focused accounting, therefore, seems like a plausible way for corporates to prioritize nature-related risks and opportunities. One way corporations can account for nature is to assess resource efficiency via an input approach--that is, the total input of natural capital that goes into a product across the value chain (where the output approach measures the greenhouse gas emissions, pollution, and waste caused by the creation of that product). Using an input assessment of resource efficiency would permit the inclusion of natural capital in profit and loss accounts, offering a more comprehensive assessment of the total economic cost of production and giving a more accurate representation of profit that factors in positive and negative externalities. Such methods of accounting can also be applied at the national level.

Why Accounting For Natural Capital In Wealth Is Not Enough

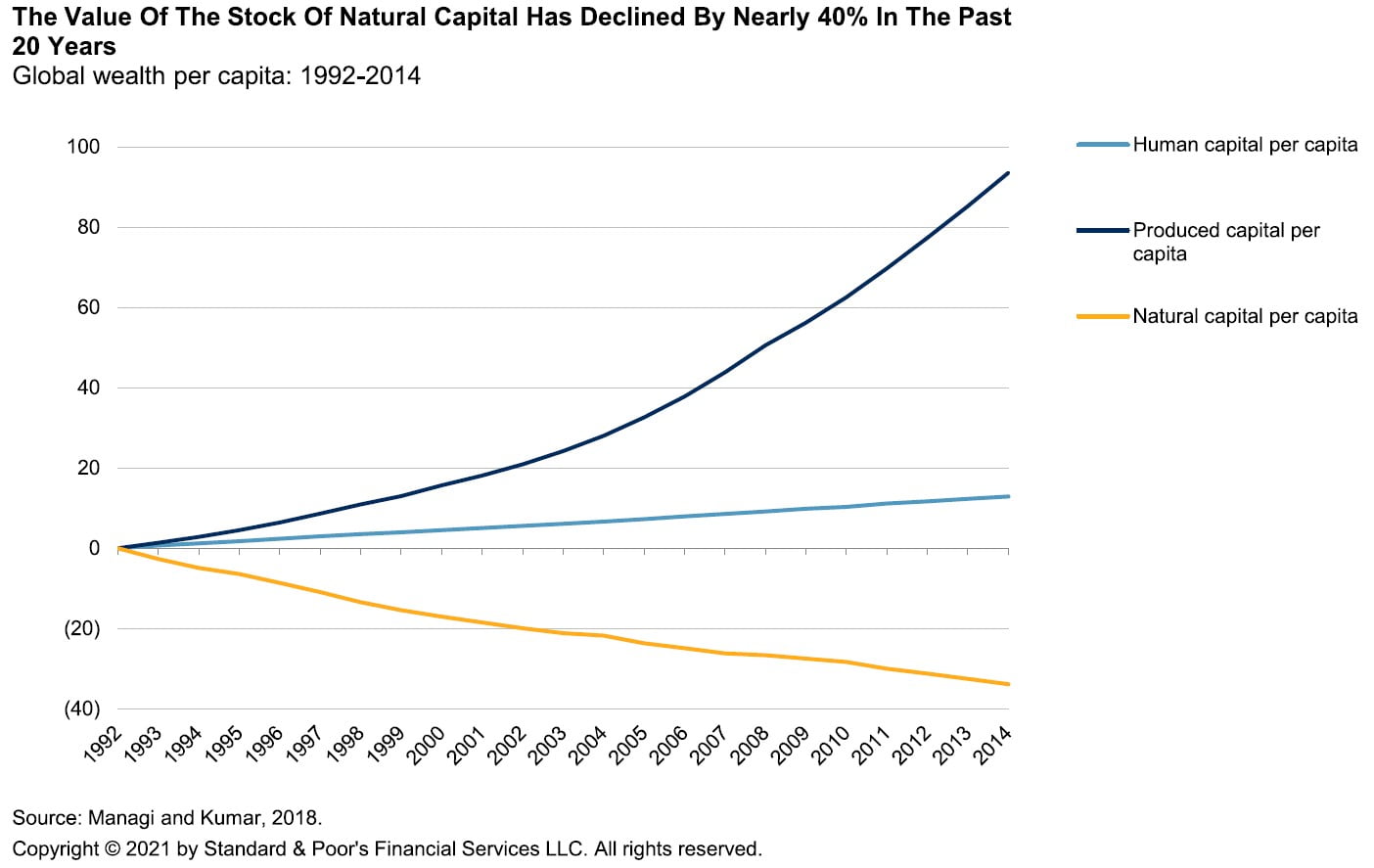

Perhaps the solution to our prodigious loss of nature lies in how we measure economic growth. One suggestion to improve our management of natural capital is to include the stock of natural resources available to us when we assess wealth. Professor Sir Partha Dasgupta of the University of Cambridge explains in his recent review that "sustainable economic growth requires a different measure than gross domestic product." He says we should adopt not just a flow (GDP) but also a stock approach to wealth--that is, one that considers the aggregate value of all capital assets--to take our use of natural capital into account (see chart 1).

Read the full article here by S&P Global Market Intelligence