Hayden Capital commentary for the third quarter ended September 30, 2018.

Dear Partners and Friends,

Volatility is back. As I mentioned last quarter, Chinese A-share markets have been declining steadily throughout the year, as US-China trade tensions have impacted sentiment. The Shanghai Composite is down -30% from its January high, and the broader MSCI Emerging Markets Index is also down -25%. The US equity markets, which had largely shrugged this off earlier in the year, finally succumbed in the last few weeks.

As of this writing, the S&P 500 has largely given up much of its year-to-date gains, in just the few weeks after the end of the third quarter.

Q3 hedge fund letters, conference, scoops etc

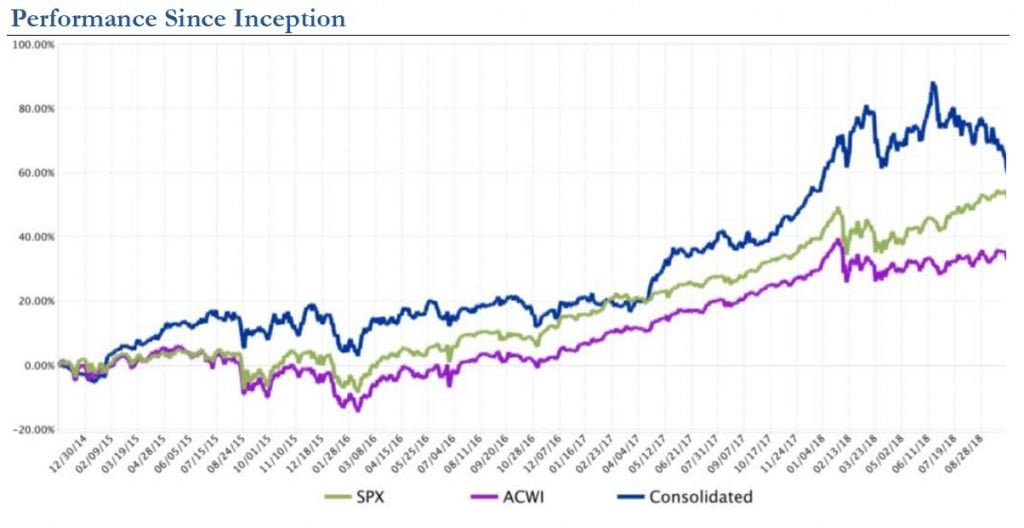

During the third quarter, our portfolio declined -5.0% (net of fees), while the S&P 500 gained +7.7% and the MSCI World Index was up +4.4%. Of this, the Chinese portion of our portfolio was responsible for -6.6% of the decline (meaning the rest of the portfolio was positive for the quarter). This brings our annualized return since inception to +12.7% (net of fees), which compares to +11.9% for the S&P 500 and +8.3% for the MSCI World Index.

Partners will find that we’ve recently initiated two new “tracking positions” in the portfolio (I describe the thinking on this below), which hopefully can become full positions at some point. We’re constantly searching for new ideas, which may provide a better long-term return than our cash holdings.

This goal has become even harder in the last few weeks though, as trims / sales of a couple of our positions have actually increased our cash holdings. While our cash balance remained steady at 8.5% throughout the quarter, we sold our remaining position in Markel (described below) after the quarter-end, which has since driven our cash balance up.

My hope is that given the increased volatility, we’ll have an easier time deploying this capital, and upgrading our portfolio quality over the next few years.

How Much Should We Risk?

In equity investing, there’s primarily three decisions to make: 1) If you should buy a stock, 2) When you should buy the stock, and 3) How much to buy. A topic I’ve been thinking about more lately, is that of position sizing (i.e. the “how much” process).

As a research analyst, your job is to focus on the “if” & “when” portions. How’s the company’s competitive position vs. rivals? Do you think management’s long-term targets are achievable? Do you believe management and think their decision-making process is rational? What is the firm’s culture like? When is the valuation low enough, to give us a satisfactory return? The if is based on company quality and competitive dynamics, and when is based on valuation.

These are generally answerable questions, with a definitive answer. For example, while investors will differ in their exact definition of “quality”, very few investors will disagree that Amazon is a better company, in a more favorable competitive position, vs. say United Airlines. Most of the time, the disagreement instead focuses on whether “high quality” or “cheap valuation” is the more important factor in returns. In other words, it’s not the actual value of inputs themselves that cause disagreement; it’s the weighting of those inputs, which differs according to style (i.e. “quality value” vs. deep value “cigar-butts”).

But what about that last decision – the how much portion? Is there a definitive answer? Assuming the conclusion is a “buy”, as a portfolio manager there’s always the next (and harder) question of how much capital should we risk on the position? It’s the manager’s job to implement the idea. Arguably, this has an equally large impact on portfolio returns than what to buy. Ever since my college internship days, I’ve been searching for a consistent / definitive answer to this, and I’ve yet to find one.

I remember watching an interview a year ago, which was a conversation between two highly-regarded hedge fund managers (I believe it was Kyle Bass of Hayman Capital interviewing another manager on Real Vision TV, but I can’t quite remember…). What I do remember though, was that the first question he asked off the bat was: “How do you size your positions”? This wasn’t just a fluff question meant to fill time… you could tell it was the most important question in his mind, and he genuinely wanted to get his peer’s insights into such a crucial issue.

In a separate interview, Bass stated “even the best [investment managers] in the world struggle with [position] sizing”. He goes on to say that while he assigns probabilities to an investment’s success, the ultimate decision on how large to size it is still based on his own “conviction level” (LINK). Although hedge fund managers will never publicly admit it, this basically translates into “we go by gut feel / our intuition”.

With a slightly different twist, at one of my prior employers, the decision was largely based on relative attractiveness – “Is this new idea better than our worst idea? If so, is it better than our second to last idea?” And so on, until it made its way up the list and found its relative position and position size (higher conviction names obviously had larger weights, and since the fund was fully invested, often meant needing to kick out a company to replace it).

Others investors, such as Mohnish Pabrai in his book The Dhandho Investor, describes equally weighting all his positions in a 10 by 10 portfolio (10 positions at 10% each). He found that often his judgement of conviction in a position was wrong (the lessor conviction positions would outperform those at the top), and therefore equally weighting was a solution to this4.

Even methods such as the Kelly Criterion, probably one of the most researched formulas in the field of probability theory, has its flaws (LINK). For example, for investors with concentrated portfolios who purchase 1 - 2 new stocks a year, the sample size of bets over an investing career is simply too small. The deviation / volatility would be too large for most investors to handle emotionally, and due to the larger deviations, has a higher chance of the portfolio sustaining a permanent impairment of capital. Because of this, it’s likely more useful for traders who can make hundreds or thousands of bets per year, but not as much for concentrated investors.

I mention these examples, to illustrate that there’s no uniform or “right answer” to such an important question. Investors smarter than myself struggle to come to a consensus on it, and I’m starting to believe that the “optimal” method is more dependent upon each investor’s emotional temperament than anything else.

It’s like dieting successfully – you need find a method that fits with your inherent preferences. For example, if you love butter and bacon, you’d probably have an easier time with the Paleo diet than drinking Green Juice all day. It’s finding the right match of [personality + method] that’s more important for success (and increasing the odds of sticking with it), rather than which diet method you actually choose (LINK).

If this thesis is right, then how do you find what sizing method is right for you, given your personality as an investor? Once you pick a method, how do you know it’s the right one for you, and that there isn’t something that’s better? In addition, this may mean that the method that worked so well for your boss, may not be suited to your own personality (hence partly why many managers, whom upon spinning off from “brand-name” funds, fail to live up to their former employer’s investing record).

On top of this, the process gets even harder, since the information we receive & the odds on our bets are constantly changing. Similar to poker, we’re not just making an initial bet on our starting hand… rather we constantly need to decide to whether to raise the stakes or fold, as each card (new information) comes out. This means that your position sizes are always in flux, and the theoretical “optimal” size (if it exists) is changing.

These are real issues, and I don’t have a magic answer for it. Our position sizes typically range from ~5 – 15%, dependent upon the stability of the business’ economics, where is it in the company’s lifecycle (what stage of the S-Curve is it in, what’s the market share vs. total addressable market), are there competitive threats or other risks on the horizon, among other factors. All of these factors get lumped into what managers call “conviction” in an idea, and is where the saying “investing is an art, not a science” comes in. However, this doesn’t mean that we should continually try to improve the process, and add more “science” behind the decision-making process.

**

Relatedly, for tough questions such as this, is it possible to implement “scientific” processes, such as running small “experiments” with the portfolio, to see if there are better methods? And more importantly, to test what our emotional responses are under these changes?

For example, a new “feature” we might wish to test, is say we’re interested in investing in earlier stage companies (pre-profitability, near the bottom of the S-Curve), and think we have a framework hypothesis to evaluate them. How do we test this process? Additionally, even if the framework is right, how do we know we have the emotional capacity to invest in these types of companies? Even if it’s not early-stage companies, maybe we want to invest in “internet” companies or cyclical companies or deep-value balance-sheet based stocks. Each of these requires different frameworks, that have to be tested.

The easy answer would be to not do it, and just stick to what we know. “Style drift” is a dirty word in the investment community, and it’s usually better to stick to what’s worked. However, the issue is that market environments change, business models change, and the types of companies that make great investments change. It only makes sense that when the investing environment changes, you have to adapt and change yourself.

As investors, our “product” is our portfolio, and as such we should constantly be trying to improve it for our customers (either personally or for your LPs). If we aren’t constantly seeking to improve our processes or add new “features”, we run the risk of becoming old and irrelevant. The faster the industry environment changes, the harder companies have to work to improve their product (for example, the speed of product iteration is much faster in the Tech industry than HVAC companies). I’d argue that with financial markets constantly evolving and sources of “alpha” shifting, this is more important for our own industry than many of those that we’re invested in.

One solution may be to learn from how “real” operating companies find answers to such questions. Many times, when companies roll out a new feature or advertising campaign, they have no idea how customers are going to respond (Amazon Fire Phone anyone?). To prevent permanent damage to the core business, companies will launch a new advertising campaign in a small market first, before seeing the results, and rolling it out nationwide. Or conduct trial tests for a new feature, to gauge the customer response, before rolling it out to the entire user base (for example, Facebook is trialing its Dating feature in Colombia first, to test the results without affecting its more important markets in case it fails; LINK).

Perhaps as investors, we can do the same with our portfolios? Except we wouldn’t be testing customer response, we’d be testing our own decision-making processes and our emotional responses to them. Perhaps we can portion out a part of the portfolio (say less than 5%), as an internal R&D facility for testing new frameworks5. If we’re wrong, it won’t have a large impact on the portfolio. But if we’re right, we have a new “tool” that’s been battle-test, to lengthen the duration of firm and investor’s returns.

This is something that I’ve been thinking about, and have already started instituting it in a small way (one of the tracking positions mentioned below, is part of this initiative). If anyone has thought deeply on these subjects, or has contrary opinions, I’d love to hear them. Our frameworks and processes are always a work in progress – one way to make it better is incorporating thoughtful feedback.

Portfolio Updates

JD.com (JD): Over the past few months, there’s been a couple negative developments for our JD.com position. First, in early September news came out that Richard Liu (the founder & CEO) was accused of sexual assault while completing a course at the University of Minnesota, as part of the Carlson School of Management / Tsinghua University’s Doctor of Business Administration program6. Most of our partners will already be familiar with the situation, so I’ll won’t rehash it. However those who aren’t can read up on the details here (LINK; LINK2).

Since the initial reports, the police have finished their investigation, and no charges have been filed in the subsequent two months. Richard was released from police custody the next day, and is now working back in China. Additionally, his attorney, Joseph Friedberg, who has a pretty stellar reputation as one of the best criminal defense attorneys in Minnesota, even went so far as to state “I would bet my law license that he’s not going to be charged.”

The female student accuser, in the meantime, has retained two civil attorneys: Florin Roebig (a firm which earned its reputation in Florida Personal Injury cases and doesn’t seem to have much experience in sexual misconduct cases), and Hang & Associates (a small Flushing, NY based law firm, who’s specialty is unpaid overtime cases in the hospitality / restaurant industry, representing immigrant workers). Despite the odd choice of attorneys, my best guess is the likely outcome will be a civil settlement out of court between Richard and the accuser, in an effort to make this headline “go away quickly”.

The more concerning issue, however, is that the event highlighted a potential flaw in our investment process. After the news came out, I started digging a bit deeper into the personal reputation of Richard. In public,

Richard is known for coming from a humble family background, having built JD from a small kiosk in Beijing to the $35 Billion business it is today, always treating his employees well (for example, calling his deliverymen “brothers”, and paying them above industry standards), and building JD.com with the idea of trust, integrity, and always playing the long-game.

However, the responses I got back from several sources after the incident, who are current or former employees, were contradictory to this image. In particular, these sources all had separate anecdotes for Richard’s inappropriate behavior, and how it’s a widely known secret within the company that he likes to “flirt with young trainees” (we can talk in more detail about these stories offline). During the initial research process when I was looking into the company, I had spent considerable time looking into the corporate culture of JD7. But in hindsight I hadn’t verified the personal background of Richard, as hard as I should have. These rumors of personal character were knowable for those asking the right questions, and it was a mistake of the process to overlook this aspect8.

**

Having said all of this, the next question is how much does Richard Liu’s personal life factor into JD.com as a company and as an investment? Judging by the stock’s initial reaction after this news broke, the market thinks it’s ~20% of the stock price.

However, I’d argue that there are other issues that JD is facing, which have a far larger impact on the company’s future value. Among them are JD’s lack of a data-driven culture vs. competitors (see previous footnote on culture), inability to court top tech talent due to this, Alibaba’s impressive ramp up in its Cainiao logistics capabilities (especially in Tier 1 cities) in the last few years, and the top-heavy management style of the company. JD is addressing some of these issues, such as implementing a rotating CEO program for its JD Mall division this summer, but it’s been slower than investors would like.

These factors are important, but as investors we also need to weigh the trade-off between the current state of the company and price too. The broader thesis outlined in our previous letters remains largely intact.

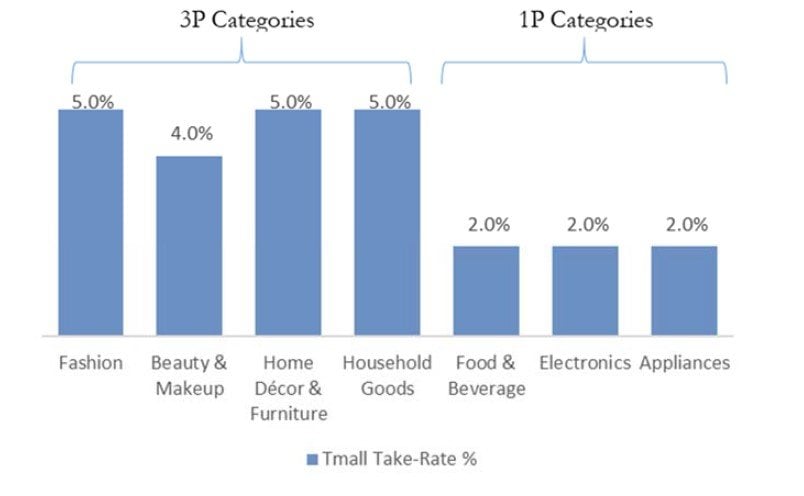

Simplistically, the company is on track to do ~$70BN in sales this year, and $100BN in 2020. Electronics and appliances make up ~75% of JD’s revenue mix, which due to the nature of the categories carry lower-margins vs. say apparel or general merchandise (see below for Alibaba’s TMall take-rates, as an example)9. If JD can simply maintain a 2 - 3% margin on this category, the profits by 2020 would reach at least $2BN. This would equate to a 16x EV/EBIT multiple, growing at 20% y/y.

TMall Take-Rates By Category

TMall Commission Fee Schedule

Additional levers, such as category expansion into FMCG (similar margins, smaller order sizes, but higher order frequency / volume) or general merchandise (higher margins, smaller order sizes) would give the stock considerable upside optionality. This gets even more attractive if we back out the logistics and finance divisions, which have both raised external funding and may be individually listed at some point. Excluding these divisions, with JD’s stake worth ~$24BN (at the last round valuations), the core retail part of the business comes down to just a ~5x multiple.

Rest assured I’m watching these value-drivers closely, as competitive advantages change due to the intense competition in the industry. I promise to keep our Partners updated with any new developments.

Markel (MKL): We finally sold out of our remaining position in Markel, at an average price of ~$1,190. It was one of the original positions in the portfolio, which we’ve owned the name since the founding of Hayden.

When we first purchased Markel, the initial thesis revolved around:

- Being able to purchase a diversified portfolio of securities, which would likely appreciate at similar or higher rates than the S&P 500,

- The market value was trading at a discount to my valuation of this portfolio, so our returns would be boosted further as this valuation gap closed, and

- Given our large cash position at the time, it was a decent place to park some excess cash while we found other places to deploy

Although Markel is primarily an insurer (and a very good one, with combined ratios of ~96%), I’d argue the operating insurance business only accounts for ~5% of Markel’s share value. The primary goal of the insurance arm for shareholders is to underwrite profitably, so that the business can “borrow” funds from the insurance float to invest in other securities. So long as the insurance unit is profitable, this “debt” never needs to be paid back, in addition to effectively getting paid to borrow this float.

If an investor is comfortable with the above, then the stock’s valuation primarily revolved around the Net Investable Asset value of the portfolio, which was ~$1,100 when we first made the investment. At an initial price of ~$690, we were buying this portfolio for 63 cents on the dollar.

Over the years, the stock has compounded from our initial price of ~$690 to $1,190 at final sale, for a ~72% return (15% CAGR) over four years10. The value of the portfolio and underwriting profits have both grown, albeit at a much slower rate than the stock. For example, the book value has grown 33%, but the multiple (price-to-book) has increased from 1.2x to 1.7x in the last few years. Given the shares now trade at less than a 10% discount to our calculated value, I decided to exit the position.

New Tracking Positions: Over the last few months, we’ve added two new “tracking positions” to the portfolio. Both of these positions are in the low-single digits, and together make up less than 5% of the portfolio at cost.

The two businesses are very different – one is in Southeast Asia; the other is in the US. One sells $2 items, the other $20,000 items. Each company has qualities that I like, but differ as to what I’d need to see to make them “real” positions.

Given the small position sizes though, even if we are right or wrong about the stocks, it won’t have a meaningful impact on our performance either way. So why establish these “trackers” at all? Well the answer is that sometimes the timing of your research process and when the market decides to give you great bargains doesn’t line up. It’d be amazing if every time you finished researching a company you wanted to buy, the stock would decline 50% just for you… but that doesn’t happen.

So occasionally we’ll have completed 70% of the work on a company, think there’s a high chance we’d like to own it at some point, but still have some remaining detailed questions we’d like to answer… and then the broader market sells-off, offering us a great price11. Do we wait to finish the remaining 30% (typically consisting of primary channel checks), and risk the market moving away from us by the time we’re done (often weeks / months later)? Or do we establish a “toehold” position now, keep it small, and finish the research while owning a small piece?

I sometimes choose the latter. Especially if there’s a near-term catalyst that could cause shares to rise, and the current price is attractive enough that it allows me to be comfortable that there is little chance of us losing money – despite not having all the answers just yet (or as much as we could potentially get). The idea is to make this a “two-way door” decision (as Bezos would put it) – small enough that it’s easy to reverse if we don’t like what’s on the other side12.

Additionally, these trackers have the added “psychological” benefit of creating urgency. There’s nothing like staring at a position daily, worried about what might be lurking in the 30% of unknowns / having that capital at risk (albeit small), to ramp up the research effort quickly.

The last time we had tracking positions in the portfolio was in 2016, after Brexit. These were companies which I had done ~70% of the necessary work on, and the broader market sell-off after Brexit offered up some prices that were too good to pass up. Ultimately, these stocks left the portfolio just a few months later, since I ultimately made the decision that the quality wasn’t as high as our other ideas (most notably Zooplus) – but we still ended up making a nice profit, due to the valuations they were purchased at.

Given we’re still finishing the research process on these names, I’ll refrain from talking about them further. Additionally, note while I hope they can become more meaningful positions at some point, it’s also possible that they will similarly exit the portfolio in a few months.

Conclusion

This semester, we welcome Philip Kor to the team, as our newest intern. He’s based in Singapore, and it’s the first time I’ve taken on an intern to work remotely. I’ve known Philip for almost a year now, and have been constantly impressed by his shared investment philosophy and dedication to learning the investment craft during that time.

Over the last couple months, his geographic location has actually proven valuable, as we studied companies in Southeast Asia. Given that investment research is generally a solo effort, the distance hasn’t been an issue, and we’re in constant contact via email and weekly calls. The downside is that this often requires Philip to stay in late in the office (our calls often last for hours till close to midnight, Singapore time), which I greatly appreciate!

Just a few weeks ago, I also got back from Shenzhen for the ValueAsia Conference. This is my second trip to China in the last few months, and it was great to meet fellow thoughtful value-investors focused on the region. We got to tour BYD’s factories, visit a Hema supermarket, and listened to ~16 presentations over two days.

As usual with these types of events, the best learnings and exchange of information happened informally, over meals, or late into the night over a few beers. Thank you to Graham, Mike, Lashan, Rob, and Carlo for putting on such an informative event. I can’t wait for next year’s.

**

It’s hard to ignore the volatility in the markets these last few weeks. Everywhere we turn – Bloomberg TV, Barrons, FinTwit, even our President’s tweets (LINK) – are talking about how October was the worst month in years for the markets (since 2011 for the S&P 500, and 2008 for the Nasdaq).

However it’s during times like these, I remember the studies showing how on average investors under- perform the S&P 500 by 3-4% a year. This isn’t because they have higher allocations to “safer” assets (the studies only look at the equity portion of the portfolio), but because individual investors tend to jump in & out of the markets based on emotions, and try to time the swings.

For example, Dalbar (one of the leading publications on this subject) has found a ~3% under-performance for equity investors on average, over a 20 year period (LINK). While some of the difference was due to investors needing capital for other purposes during in-opportune periods (for example, needing to cash out investments during a recession, due to personal hardship), the majority of the difference could be accounted for by investor’s emotions (i.e. trying to avoid further losses, and ending up selling at the bottom).

We’ve worked hard to structure Hayden, so that we don’t fall into this trap. While we don’t impose any lock- ups, I’m proud that during this period of volatility, we’ve barely heard a peep from our client base. I hope this is an early signal of the strength of our asset base, and the curation of our group of investors – especially for when times get even tougher (because trust me, at some point in the life of portfolio, it’s going to happen)13.

By remaining focused on our investment goals (investing in companies that can compound capital over the next decade), and striving to match the asset / liability duration of our capital (when we expect our investments to come to fruition vs. when how long our clients are willing to provide their capital for), we already have a significant advantage over the rest of the market.

On that note, we’re always open and willing to speak with any potential partners who may have a similar mind-set. If you know someone who you think would be a good fit for our strategy and Hayden Capital, please have them reach out.

In the meantime, if there’s ever anything that I can help with, please feel free to reach out or stop by the offices. I hope you and your family have a great holiday season, and I look forward to writing to you next quarter.

Sincerely,

Fred Liu, CFA Managing Partner

This article first appeared on ValueWalk Premium