The 2020 US election kicks off next week with the Republican and Democratic caucuses in Iowa. While President Trump will almost certainly be the Republican nominee for president, the eventual Democratic nominee is much less obvious. Whoever that eventual Democratic nominee is will face an incumbent president at a significant handicap, given the strong political headwinds facing Trump. Legislative policy is unlikely to be significantly impacted since Congress will probably remain split, making it extremely difficult to pass any large, non-bipartisan legislation. However, other policies that would be the purview of a Democratic White House, such as deregulation and the environment, may pose threats to certain sectors and firms, as well as US bond yields. Nevertheless, we remain positive on growth assets (US, but also more broadly) since the macro picture remains supportive, even if sentiment may reduce their risk-reward.

Q4 2019 hedge fund letters, conferences and more

The Rules and Calendar of the Primaries Mean We Will Not Know the Eventual Democratic Nominee for Some Time

The 2020 US election begins with each party’s presidential primary, during which states choose delegates to their party’s national convention later in the year. These delegates pledge to vote for a particular candidate at the convention, and the candidate with a majority of delegates is selected as the party’s nominee for the presidential election in November.1 In the absence of a tail event that would preclude Donald Trump from seeking re-election, it is safe to assume he will be the nominee of the Republican Party.

For the Democratic Party, the picture is much less clear. No candidate has consistently polled above 30%, making it hard to say there is a clear front-runner. Nonetheless, the rules and timing of the Democratic presidential primary are helpful to understanding how it may play out. Overall, there are 3,979 Democratic pledged delegates to be selected, requiring a potential nominee to secure 1,990 of them to attain a majority during the first round of voting at the convention. In addition to these 3,979 pledged delegates, there are 771 “automatic” delegates, who were called “superdelegates” in previous primaries.

Unlike past Democratic primaries, where these superdelegates could significantly sway the vote, they will not be allowed to participate in the first round of voting at the convention.

Rather, they will only vote if there is a brokered convention (no candidate gets a majority on the first ballot), essentially acting as a tiebreaker in additional rounds of voting. So far, many of these automatic delegates have not endorsed a candidate yet, and this will likely remain the case so that they can maintain their flexibility to avoid a messy, drawn-out convention.

Unlike the 2016 Republican presidential primary, which had widely varying rules for allocating delegates to candidates for each state, the rules for the 2020 Democratic primary are rather uniform from state to state. Delegates are allocated proportionally based on their statewide vote share, along with their local district 2 vote share,

with a 15% cut-off (i.e., any candidates with less than 15% of the vote are excluded). Nearly 65% of the pledged delegates (2,591) are allocated using the local district vote share, with the remaining 35% (1,388) allocated using the statewide vote share. This means that a candidate who misses the 15% cut-off at the state level may still pick up delegates at the local level if they did better than 15% in some districts.

By and large, however, one should expect delegates to be allocated proportionally by vote share, so as the primaries come closer and there is more accurate polling, the allocation of delegates will become clearer. However, given the state of polling today (see below), the inability of any candidate to take and hold a commanding lead, and the proportional allocation of delegates, there is a reasonable probability that the nominee will be uncertain heading into the Democratic National Convention in mid-July.

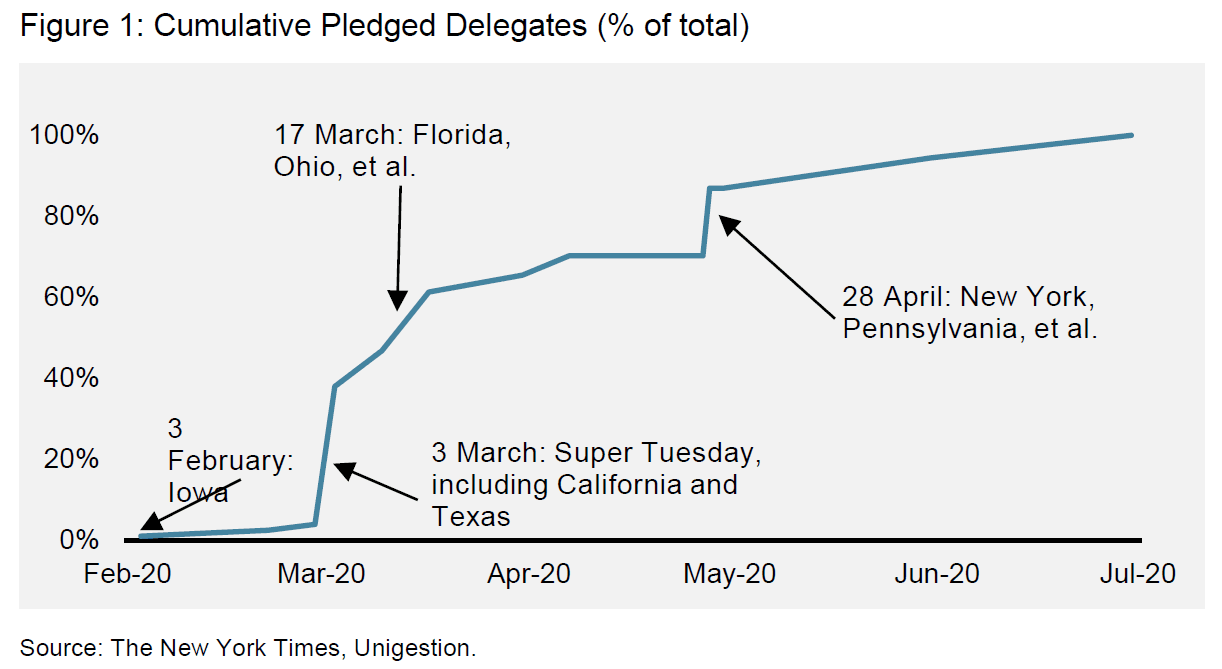

Figure 1 below shows how the pledged delegates will accumulate over the first half of next year, along with some important dates to watch closely for signs of Democratic primary voters coalescing behind a candidate.

The Eventual Democratic Nominee Remains Unclear

Following the 2016 presidential election, the Democratic Party has been pulled in two different directions: the progressive wing of the party has pulled it further to the left, while moderate Democrats have pulled it to the centre. Thus far, this tension has largely played to the benefit of Democrats, allowing them to field more moderate candidates in right-leaning elections, while more progressive candidates have scored wins in more left-leaning elections. Indeed, during the 2018 midterm election, Democrats took control of many seats in the House of Representatives by running candidates in Republican-held districts who were moderate and could capitalise on voter unease with President Trump.

However, the presidential primary is a national election and thus lays bare these two divergent views on the future of the Democratic Party and the country as a whole. On one side, the more moderate wing of the party has supported candidates like former Vice President Joe Biden (who remains on top of most polls) and Mayor Pete Buttigieg. On the other side, the progressive wing of the party has been a strong supporter of Senator Bernie Sanders, as well as Senator Elizabeth Warren. Other candidates have failed to gain traction and dropped out, while others continue to campaign, notably Senator Amy Klobuchar, Michael Bloomberg, and Andrew Yang. Figure 2 highlights how the national polls have evolved over the last year.

There are a few key takeaways from the polling data:

- While Biden and Sanders have largely held steady, Warren and Buttigieg have seen their support rise and fall, suggesting some elasticity to their coalition;

- Klobuchar, Bloomberg, and Yang have not consistently polled above 5%, though Bloomberg’s numbers have been rising as he announced his candidacy recently;

- There remains a large number of voters (nearly 20%) who are backing another candidate (there are many candidates polling in the 1-2% range) or are undecided, implying that as these voters switch preferences or ultimately choose a candidate, we may a see a large shift in the polling.

Given the state of polling and the ability of candidates to generate strong momentum (and reversals) during the early part of the primary season, it remains uncertain who the eventual Democratic nominee will be. March 3 will be an important marker, as some candidates may build momentum from Super Tuesday while underperformers will likely drop out shortly thereafter.

President Trump Is Neither Inevitable Nor Improbable

The eventual Democratic nominee will face off against an incumbent president who, by many metrics, should be a clear front-runner: the economy continues to grow at a healthy pace, unemployment is at multi-decade lows, stock markets are at all-time highs, and military conflicts have been contained (for now). However, President Trump is not the typical incumbent and faces some significant headwinds heading into 2020:

- His net approval rating (percentage approving minus disapproving of the President) has remained in the -10% to -15% range and was only positive shortly after his inauguration. No president going back to Harry Truman has maintained such a negative view among Americans for so long;

- The 2018 midterm election (as well as other special elections after 2016) has often been framed as a referendum on President Trump, and the results are not encouraging for him: Republicans lost the House popular vote by 8% along with 40 House seats (they did net two additional seats in the Senate), with voter turnout (50%) exceeding all midterm elections going back to 1946 and approaching the 2016 presidential election turnout (56%);

- Finally, Trump has been impeached by the House (in a near-party-line vote) and now faces the possibility of a trial in the Senate before Election Day. While the likelihood of getting two-thirds of the Republican-held Senate to vote for his removal is low, about 47% of Americans think he should be removed from office. Importantly, nearly 42% of independents agree, suggesting that it is not just Democrats who want to see President Trump out of office.

Of course, the actual person the Democrat Party nominates to challenge President Trump will be key in assessing the likelihood of Trump’s re-election. For now, head-to-head polls suggest the contest will be close. Figure 3 shows the average margin of Democratic candidates against Trump (so a value of 2% for Biden means that he is beating Trump by an average of 2% in head-to-head polls).4

Broadly, the election would be a toss-up at this point. No potential Democratic nominee has a clear edge against Trump. Even Biden, who had a nearly 10% lead on Trump in September last year, is tied with the President today. Moreover, there are about 10% of undecided voters, adding further uncertainty to any claim that there is a clear case for any presidential nominee. It is also helpful to bear in mind that the actual contest is nearly a year away, and we would want to see how the numbers look in the few months before the election.

For context, looking back at the last four presidential elections when an incumbent was running (2012: Obama vs Romney, 2004: Bush vs Kerry, 1996: Clinton vs Dole and Perot, 1992: Bush vs Clinton), the incumbent had a reasonable lead on the challenger for the first the first three of these contests heading into Election Day and won.

From August 5 to November, Obama averaged a 2% edge over Romney, Bush a 3% lead over Kerry, and Clinton a 10% edge over Dole and Perot combined. In the latter election, the elder President Bush trailed Clinton by about 12% on average since August and lost re-election.6 The Electoral College may play to President Trump’s benefit, but if he trails the popular vote by much more than 2% (the 2016 popular vote margin), it will be difficult to make up the deficit.

Eventual Democratic Nominees Look to Undo Trump’s

We do not expect fiscal policy to change much depending on who is eventually elected president, unless we see a significant “wave” election that gives one party a strong majority in both chambers of Congress. If Trump is re-elected and Democrats continue to hold the House (which they seem likely to do), policy will continue as it has for the last year: bipartisan measures with White House support (e.g., USMCA) will work their way into law, while other measures will languish (e.g., immigration reform).

If Trump loses but the Democrats are not able to take a strong majority in the Senate (to overcome potential filibusters), the Democratic president’s agenda will be limited to those policies that have broad appeal. There are additional measures that could be used to enact policy (executive orders, the reconciliation process, eliminating the filibuster), but these are unlikely to produce large, systemic changes or could face legal challenges.

However, as the election approaches, financial markets will react to changes in polling as investors reassess their own probabilities for fiscal policy. While President Trump has not indicated a meaningful change in his policy stance, the Democratic candidates’ policy proposals do differ significantly from current policy and, in some cases, from each other. Figure 4 presents some of the key domestic policy questions addressed by the top four Democratic candidates.

This election year will likely see a continuation of this dynamic as the marginal investor prices in the possibility of a Democrat in the White House. From our perspective, a few markets are especially exposed to this political risk:

- Corporate equities had benefited significantly from the 2017 tax cuts, passing their tax benefits nearly one-to-one to profit growth, thus any potential repricing of corporate taxes higher will be a headwind in 2020 to US equities;

- Sectors (such as metals and mining and healthcare) and firms that have benefited from Trump’s deregulation push, especially on environmental regulations, are especially at risk given that these policies are largely driven by the White House and do not typically need Congressional approval;

- The Democratic candidates’ plans for reducing student tuition and debt burdens, along with various aspects of a Green New Deal, will likely mean additional borrowing from the federal government, adding further upward pressure on US bond yields at a time when the Fed has indicated that their target rate is at a satisfactory level.

Despite these risks, we still maintain a positive view on growth-related assets in the US since we do not see at this time a significant threat of recession in 2020. Moreover, we expect many of the Democratic primary candidates to shift toward the centre during the general election campaign once they start facing the broad electorate. Nonetheless, politics has certainly reduced the risk-reward of US assets, which points us toward looking outside America for attractive opportunities.

Conclusion

Politics typically does not play a significant role in asset allocation decisions since it has limited impact on macroeconomic forces. However, over the last few years, its influence has risen significantly due to an ageing expansion that is showing signs of stable but low growth, few inflation pressures, and a rise in populism pushing back against globalism. The US is no exception, and with policy often communicated in 280 characters over the last three years, market sentiment has been quick to react.

From our perspective, the US presidential election will demonstrate whether the American electorate is as fed up with President Trump as his approval polls indicate or whether the resilient economy will make up for Trump’s faults. Even if Trump loses, we do not expect to see significant changes to policy that would seriously threaten US assets, though there are concentrated pockets of risk.

The election results have a high degree of uncertainty currently, posing a threat to the improvement in market sentiment over the fourth quarter of 2019. However, we believe the risk-reward of growth assets remains supportive, albeit less so than a few months ago.