Tollymore Investment Partners commentary for the third quarter ended September 2020, disucssing their ownership of Trupanion Inc (NASDAQ:TRUP).

Q3 2020 hedge fund letters, conferences and more

Dear partners,

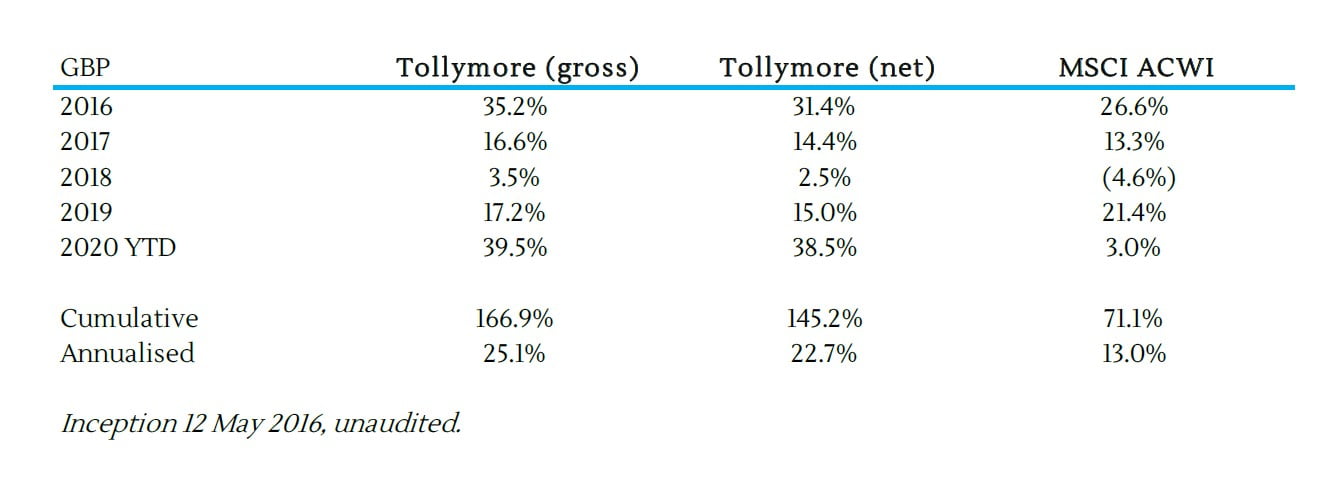

Tollymore generated returns of +39% in the first nine months of 2020, net of all fees and expenses. Investment results since inception are shown below1:

Can we profit from change without predicting it?

To manage capital patiently and successfully, it is not desirable to know everything about everything. Rather, our job is to express, through the direction of capital, insights that are anomalous or mispriced.

Our inability to predict the future severely limits the value of anticipating unknown unknowns. And it is unknown unknowns that move markets in aggregate. Due to the market’s efficiency in pricing forward expectations, making investment decisions according to forecasts about known unknowns is also a low ROI exercise. Rather, all we can do is to prepare for uncertain shocks through a general risk framework, one that allows us to own resilient, or antifragile businesses, with adaptive and innovative business leaders.

We are not trying to express anticipated thematic changes through our investment process. We are not trying to react to macro or cyclical shocks by predicting winners and losers. Of course, distressed prices due to these shocks may create opportunities, but these are unearthed via a bottom up discovery process.

The holdings in our portfolio have different business models and economic characteristics, but all are consistent with a goal to maximise the intrinsic value of a portfolio of companies, principally through the compounding of each company’s enterprise value through its own efforts.

We try to describe using first principles language whether a business is ‘high quality’ along the vectors we use to define such a concept. Without such a technique, we might fall into two traps: (a) we become enamoured with certain business characteristics that are likely to be overvalued and lead to a non-diverse portfolio, and (b) we dismiss hidden gems that may be in unfashionable industries conventionally perceived as low quality, but when examined idiosyncratically are actually wonderful businesses.

TRUP - Exploiting faulty heuristics: an example

Our ownership of Trupanion Inc is an instructive case study of: interrogating investment merits from first principles; profiting from short sellers’ different investment agenda; the value of steady business progress accompanied by fluctuating quoted prices; and the embodiment of the symbiotic value chain.

The mental shortcut

The heuristic that comes to mind for insurance companies is that they are typically mature, capital intensive businesses whose internal investments yield a cost of capital for owners. So embedded is this heuristic that when an insurance company’s management describes the company in terms of recurring revenue and maximising the lifetime value of its customers, it leads to a high level of short interest claiming a disingenuous management team mischaracterising the business.

Short sellers’ different investment agenda.

We do not short securities. A capped upside and unlimited downside2 are inconsistent with the risk framework we have described in past letters. But TRUP remains one of the most shorted stocks we own, and it serves us well to contemplate the incentives governing short seller behaviour. Because the upside is capped, short sellers are not long-term investors. We can look well beyond five years in the pursuit of satisfactory results. Even if a short seller believes a company is worth zero, an investment horizon of five years would still require an annual investment result below what we as long term long only investors might be hoping to achieve. Indeed, if Tollymore’s portfolio returns to date are the opportunity cost, their zero would need to be reached in around three years (ignoring the borrow cost). If they are aiming for a 50% stock decline, they would need to achieve this in two years, before diverting resources to the next target. It all just seems very labour intensive. And hard.

With an understanding of short sellers’ agenda, and while recognising the behavioural risks of being defensive3, let’s use their thesis to scrutinise our own set of insights:

“TRUP has an adverse selection problem. That is, by distributing insurance through the vets, they are selling insurance to sick animals. This will lead to a rate spiral.” TRUP’s competitors rely on online marketing initiatives to acquire customers. It seems logical to us that pet owners will be searching the internet for pet insurance when their pet is injured or unwell. TRUP focuses only on puppies and kittens, acquiring them when they first visit the vet. Those pet owners that take out a TRUP policy to treat a pre-existing condition quickly churn out when they realise it is not covered.

“Churn is very high”. Again, once normalising for early churn due to uncovered pre-existing conditions, the majority of churn is explained by the pet’s average life. We think TRUP has room to better educate customers in making it clear that pre-existing conditions are not covered. But in general, they do a good job at keeping customers. The lack of coverage for pre-existing conditions makes changing insurance provider costly.

“Management is overly promotional and disingenuous.” Short sellers have claimed that the CEO has referred to TRUP as a SaaS business. This isn’t true to our knowledge. The CEO has specifically stated that TRUP is NOT a SaaS business because it has low gross margins.

“The business is egregiously overvalued and should be valued like an insurance company”. We agree that it should be valued like an insurance company, because it is an insurance company. But it is growing its discretionary profit pool 30% per annum and has an RoE approaching 50% on an owner earnings basis. So, calls for 1x BV make no sense to us. After a tripling of the stock the P/B implies 7-8% sustainable growth. While no longer clearly deeply discounted to today’s intrinsic value, neither is this business clearly overvalued and we continue to own the company as a core investment.

The value of steady business progress accompanied by fluctuating quoted prices

In a decade of public documents, TRUP has never reported a quarter of sales that was lower than the previous quarter. This is not due to extraordinary execution but the result of a monthly recurring revenue model and a large underpenetrated addressable market. In the US around 2% of cats and dogs are insured. In the UK, a market in which Patsy Bloom’s PetPlan business increased penetration via a similar comprehensive product and vet distribution, one quarter of dogs and cats are insured. In that market it took 20 years to reach 5% penetration and another 20 years to reach 25% penetration. This potential for accelerating growth is not reflected in TRUP’s quoted price.

At the same time TRUP is one of the most volatile stocks we have owned, allowing us to occasionally pare back or add to our ownership when the quoted price makes such actions likely to improve our equity investment results.

The embodiment of a symbiotic value chain

A symbiotic value chain is one in which multiple stakeholders participate in a company’s value creation; success is shared with customers, employees and owners through thoughtful and transparent incentives. When the mission goes beyond profit maximisation, profit maximisation is often the result. When all stakeholders are inspired by a mission, short term sacrifices in the interests of long-term outcomes become easier. This makes for a more defensible, less replicable business as stakeholders adhere to the mission though good times and bad.

There is something special about the incentives of TRUP’s stakeholders and the economic characteristics of the services TRUP sells. Consider what a 70% loss ratio implies for the customer’s value proposition. Customers are paying an average mark-up of 43% for each dollar of premium. This would seem uncompelling for a customer seeking an ROI on their premiums. But pet owners are clearly not seeking a return; in fact, they hope that their pets are never sick or injured. Further, competitors’ loss ratios imply mark-ups in the order of 100%, highlighting TRUP’s superior value, if not cheaper price.

Even if pet owners were seeking a return on their paid premiums, there is an asymmetry in the value chain that makes it difficult to self-fund the medical needs of individual pets. Pet owners are not playing a repeated game; the average experience of the average pet, even if it were known to individual pet owners, is of limited use in underwriting the potential costs of individual pets. TRUP on the other hand is playing a repeated game using pooled data to accurately underwrite a group of pets. It is this aggregated data that constitutes a barrier to profitable participation that would make it difficult for vets to offer their own insurance for example.

Other components of synergistic value chain: (1) Trupanion Express allows claims to be paid directly by TRUP within minutes. This is great for TRUP as it allows access to more data from other insurance providers. It is great for customers there is no need to settle expenses out of pocket. And it is great for vets because it lowers economic euthanasia and allows for Plan A treatment options, and saves credit card fees, which might be 20% of their profits. An important insight here is that vets are paid a fraction of doctors’ salaries. Their careers are intrinsically motivated and mission driven. (2) Enterprise value growth is shared between employees and owners according to a transparent formula. And all employees are owners.

Multiple small insights can confer lasting unfair advantage

The discovery of these insights requires a bottom up research process and first principles thinking. They would have been missed by the quality business investor seeking ‘network effects’, ‘switching costs’, ‘capital light business models’, ‘SaaS’, ‘platforms’, ‘high net retention’, ‘high gross margin’, ‘WFH stocks’ or other heuristic du jour. TRUP has certainly been written off by many investors perplexed at why an insurance company’s price to book might be in the double digits. TRUP’s investment merits cannot be punchily summarised; unearthing them requires effortful digging and a capacity to see the wood for the trees.

Learning from mistakes: an example

Betting on revisions of progress

We used to believe that buying companies that have attractive long-term prospects, but which are facing short term, but surmountable, business problems was an attractive source of superior investment results. This may still be the case, but our investment history has demonstrated an inability to consistently profit from this.

The investments we made into TripAdvisor and Grubhub were, with hindsight, bets on a revision of fundamental business progress that did not materialise. In both cases there exist winner take most potential economic outcomes, with demonstrable barriers to entry and an owner-operator business ethos.

Yet in both cases it was our misassumption that a monopolistic outcome was unnecessary for outsized value creation. This was a philosophically inconsistent premise.

We considered TRIP part of a global duopoly in hotel meta. And in our view the principal competitor to TRIP’s product offering was the large portion of travel bookings and advertising still taking place offline. But we were too dismissive of the value that Google commands by being right at the top of the funnel for most hotel booking experiences. From this position Google has the power to inflate OTA and meta companies’ customer acquisition costs by replacing their organic results with ads or Google’s own inventory occupying the most valuable top-of-page real estate. As TRIP’s core hotel business stagnated, we were the proverbial frog in the boiling water.

Labels are bad for mental flexibility

The broader lesson here is that being a long-term investor does not mean you should not quit when you are wrong. The long-term investor badge of honour that many of us self-righteously parade around can really put our investment results in jeopardy by inhibiting the objective reasoning we are so fond of telling people we

possess.

The more subtle observation from these types of errors is that for businesses with potentially exponential success outcomes, oligopolistic participation in a particular digital migration may not be enough. As such, we expect several of our current holdings to be the outright winners in their respective industries.

One example is one of Tollymore’s largest holdings, Farfetch, a global luxury digital marketplace for brands, retailers, and consumers. We acquired our interest in FTCH for 14.4p/share in May 2020.

FTCH exists because of a compelling consumer and supplier proposition. 80% of products sold online are in a multi-brand environment. This is evident in brands’ historic willingness to have concessions in department stores – that is where the footfall is. Luxury brands, in return, gain access to 2.5mn luxury customers across the globe. Given consumers’ preference for shopping in a multi-brand environment, brands have a choice to either partner with a vertically integrated retailer, or a marketplace. The clear preference for marketplace partnership is a function of (1) unit economics and (2) control.

FTCH’s take rate is c. 30%. Under traditional linear industry economics, a product costing $20 may sell for $100. The retailer typically keeps most of the $80 mark-up, perhaps around two thirds of it. The brand margin is therefore c. 25%. For a brand selling directly on FTCH, this might double to 50%, which is what is left after the product cost and FTCH’s 30% take rate are deducted from the retail price.

In addition to this gross margin advantage, brands can achieve incremental sales by making their inventory available to a global luxury audience without increasing their invested capital or diminishing their returns on capital. The high take rate is also supported by special characteristics of luxury products – high gross profit products and a fragmented supply base characterised by family-controlled companies seeking to protect brand integrity. By partnering with FTCH, brands retain control over visual representation and pricing, mitigating potential concerns around brand dilution.

The right model for industry domination

FTCH does not compete with any other large luxury marketplace. If the same pattern of disruption happening in music, travel and communication, is repeated here, then the leading player will be a platform, not a retailer or a brand. CEO and founder Jose Neves is playing for winner take all. His strategy is predicated on the logical assumption that consumers will always gravitate to one single app, forcing vendors to gravitate to one single platform. And we think that this is most likely to be FTCH given its scale advantage and given it has found itself, through good fortune or managerial foresight, to have the right model at the right time.

With my best wishes,

Mark