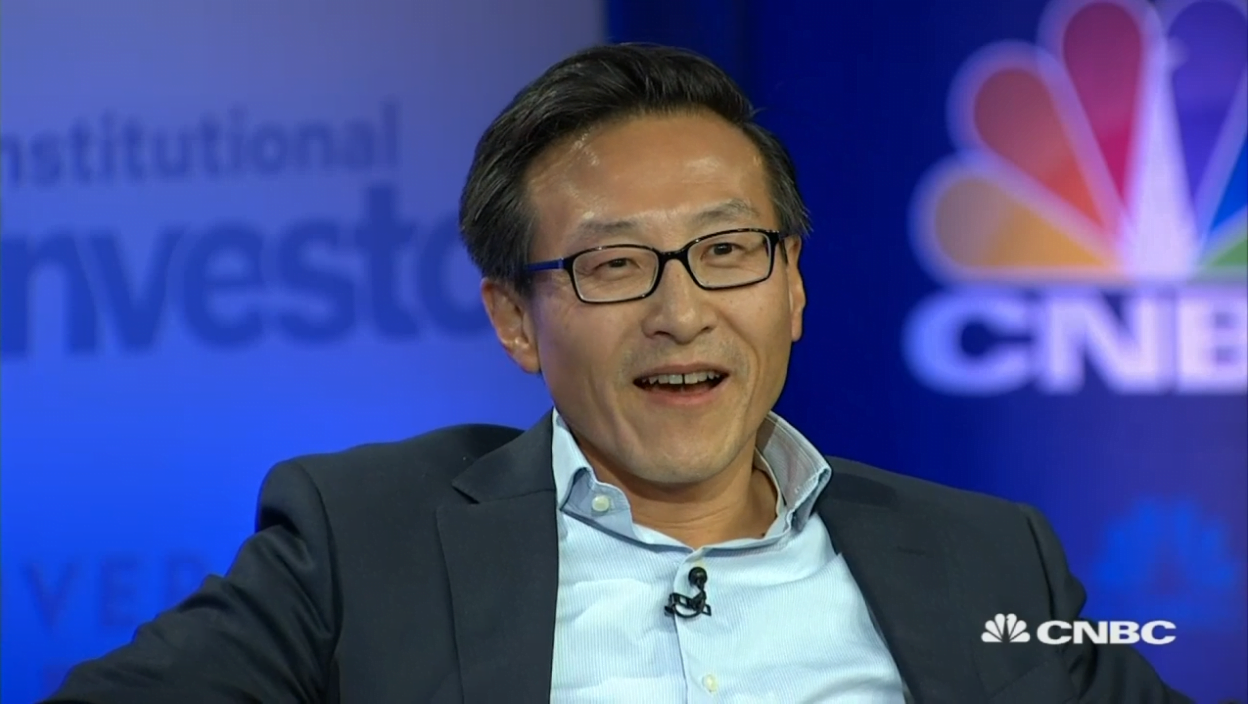

CNBC Exclusive: CNBC’s Andrew Ross Sorkin interviews Mary Callahan Erdoes, Joseph Tsai and John Vaske From CNBC Institutional Investor Delivering Alpha Conference

Q2 2020 hedge fund letters, conferences and more

Realtime Transcription by www.RealtimeTranscription.com

Interview with Mary Callahan Erdoes, Joseph Tsai and John Vaske

ANDREW ROSS SORKIN: Tyler, thank you, my friend. Appreciate it very, very much. And it's a privilege to be with all three of you on this very special occasion, our ten years of doing this altogether now. We have so much to talk about when it comes to the international space of investing and the idea of globalization or, rather, deglobalization. That's where I want to start this conversation, given some of the comments that Treasury Secretary Mnuchin just made about globalization, about the relationship with China, I wanted to start specifically with Joe, given the experience you've had over all of these years with Alibaba, and I think your appreciation and understanding of what the world is starting to look like one way or the other. But I'm curious just in reaction to his comments about transparency, how you think about the current state of globalization or deglobalization, and what you think it really means for investors.

JOSEPH TSAI: Hey, Andrew, it's a pleasure to be on the show. I have -- in my background, there's a number of logos of animals, looks like I'm in a plush toy store, they represent each of the business units of Alibaba, I just wanted to make that clear. So on your question about deglobalization or this concept of decoupling, I think that people talk about that in the context of China, and a lot of companies consider moving their manufacturings away from China. But the fact right now is if you look at the global electronics value chain, China is 81 percent of the assembly value and 64 percent of the components. So are we going to be able to completely rip out this manufacturing away from China and spread it around the globe? I think it's not going to go to 0, it may go down maybe 10, 20 percentage points, but China is still going to be a very significant part of the global economy, making stuff for the rest of the world as a big manufacturing center. And there's a couple of important reasons for that. Number one, if you just look at the demographics. As you know, China has 1.3 billion people in population. They have 800 million people in the labor force, that's the largest labor force in the world. 150 million skilled labor force, so you know, things like tooling, talk about manufacturing. And you know, you look at some of the Southeast Asian countries, Indonesia, big country population, but only about 130 million in labor force, Vietnam has 60 million in labor force. So China still outsizes everybody else in terms of the size of its labor force, especially skilled labor force for manufacturing. So that's one reason it's not going to be possible to completely decouple your manufacturing from China. The other reason is, China today has a middle class -- rising group of middle class consumers. Secretary Mnuchin has referred to 300 million middle class consumers in China. That's about the same size as the U.S. population. So companies from around the world will want to tap into that middle class and sell into that middle class. And by the way, Alibaba is in the middle of that. We're very well positioned to help companies in America, in Europe, around the world, to sell to middle class consumers in China. And guess what? If you want to sell into China, you need to set up manufacturing there. To give you an example, Tesla, they made a $5 billion investment in Shanghai. Now Tesla produces about one-third of their global production in China. Why? Because they wanted to sell to Chinese consumers. So I think this concept of decoupling, yes, it's happening. But you're not going to completely decouple the various economies, especially in China's case. The manufacturing base is going to be very much intact.

ANDREW ROSS SORKIN: Thank you, Joe. Mary, speak to this in terms of how you're advising clients, though, right now, and the potential risks involved with investing in China, how you might even be suggesting that they do invest if, in fact, you're arguing that they should invest in China right now, and what the political risks are. You know, lots of people look at an apple and say, you know, what happens if there is a backlash in China? Maybe they're protected from the manufacturing piece that Joe just discussed, but how do you think about it?

MARY CALLAHAN ERDOES: Yeah. So thank you for having us all. I think the program has been great, and Secretary Mnuchin started us off so strongly this morning with a positive tone. When we think about allocating our assets around the world, one of the hardest things we do with all of our clients is to try to get away from this home country bias. This panel is called "international." And, of course, "international" means very different things for Joe than it does for John, than it does for a client that's sitting in the U.S. If you just look at most U.S. portfolios, most U.S. people look at the U.S., and while it's only 25 percent of GDP and it's 36 percent of the stock and bond markets around the world, it's about 72 to 75 percent of most people's portfolios. So getting them out of that home country bias, diversifying around the world and, importantly, in places like China. China is the number 2 bond market in the world, it's the number 2 stock market in the world, and it's going to be the number 1 GDP market in the world by 2030. So not understanding China and not investing in China and not understanding the dynamics of everything Joe just talked about, it would be irresponsible to be an investor in today's world if you didn't do that. So really understanding that when you buy any particular company, you have to do a much more sophisticated look-through to what the company is producing and where their revenues are coming from, than just an indice or the beta might unveil itself. So if you're buying a BMW, are you buying a German company? You're buying a German-domiciled company, but they sell more cars and more revenues come from China than any other country in the world. If you buy Texas Instruments, very little comes from Texas. Actually, less than 12 percent of their sales are in the U.S. Greater than 50 percent of their revenues come from China. General Motors sells more cars in China than it does in the United States of America. So making sure that you're well aware of what's happening with these global Fortune 500 companies. If you stay too focused on the U.S., if you just look ten years ago when we were focused on these same topics after the great financial crisis, we said: What does the global landscape look like? Well, 153 of the largest 500 companies were in the U.S. and 29 of them were in China. Here we are today, there's a little less from the U.S., because other companies and other countries have risen so strongly. So only 121 of the U.S. companies. Thankfully, JPMorgan standing strong in that list. But now 124 come from China, more than the U.S. Alibaba being a very strong component of that. So understanding where you're investing, where the dynamics are. And I want to make one more comment on what Joe just said. When you think about technology and the investments there, think about the backdrop of China. You know, China is a very friendly tech country when it thinks about its investing in its own companies and its reducing the obstacles for tech companies to be successful, and the U.S. had a history of thinking about regulations and taxation on the tech companies. And so you have to think about where the dynamics are and making sure that you're giving the portfolio the greatest chance for diversification and just understanding where the flows around the world are going.

ANDREW ROSS SORKIN: Thank you for that, Mary. Let me ask John, when you've thought about how your portfolio looks, I'm curious if it's changed over the past 12 or 18 months as this deglobalization theme has become a stronger concept, and what it really means in terms of how you're allocating money today.

JOHN VASKE: Thanks, Andrew. Look, it's a real privilege to be part of the program and to be on this panel with both Joe and Mary. Just a little bit of context. They just announced our results recently. China, by way of value in the market is our now largest market at just a little under 30 percent, Singapore being the second at about a quarter of the portfolio, and the U.S. being the third at about 17 percent. But the way we got there was not by way of a sort of global allocation, if you will. Several years ago we took a hard look at the portfolio and realized that we were underrepresented in what we thought were going to be the themes and the trends of the future. So those things were around social progress, you know, rising affluence has already been discussed by the others, you know, longer life spans, sustainable living and then tech-enabled, you know, trends and sectors so, you know, things that create connectable smarter systems, connected world, sharing economies. And when we started to think about those trends and where we want to put our incremental capital, if you will, we realized that we were underrepresented in the U.S. But when you think about both China and the U.S., they have all of those things that I just described ready and available in terms of investment opportunities. So we're firmly in both places, we'll continue to be so. Obviously the current landscape makes it a little bit more difficult, creates a little bit of volatility. But also when you look at those trends against the COVID environment in which we've been operating some of those business models, so for example, our financial services, we wanted to go into fintech and payments, you know, with large cap names like Visa, PayPal, MasterCard, but also with some of the earlier-stage companies like Bill.com. They would tell us over the course of the next several months, they will have accelerated one or two years of kind of what their otherwise plan would've been. So, it's not by way of regional allocation. Again, it's going to create a little bit of volatility along the way, but those trends are present in both markets, tech-enabled, innovation with the services that go around it, but it's got to be a domestic consumption-driven sort of mandate, if you will.

ANDREW ROSS SORKIN:Right. And Joe, really keying off of what John just said, I'm curious if you -- as a Chinese business executive, take us inside the room as the board and your colleagues and peers have watched this whole TikTok saga play out because I think people wonder if that's going to be instructive of the future and whether this is really about TikTok or maybe about 5G or other issues, and how you think about that given the comments that the Treasury Secretary just made and clearly the interest that seems to -- and spotlight that seems to be on this issue.

JOSEPH TSAI: Sure. We're not in the room with all the discussions with respect to TikTok, so really can't say exactly what is going on, but it seems like that deal is probably going to go through and obviously there's an overarching concern for national security. And in Alibaba's case, we have several years ago made a decision that our core market is China. And we like developing economies, so if we're going to expand internationally, we're going to expand into more emerging markets, places like Southeast Asia, where we have a very large E-commerce business as well as logistics business, in six countries in Southeast Asia. We have shied away from, you know, running businesses that focus on consumers in the western markets, especially in the United States. Our activity in the United States is purely focused on helping American companies, that means brands, small businesses, and even the farmers, for them to access the big Chinese consumer market. And just to take a step back in context of how big the Chinese consumer market is, China's economy is 14 trillion U.S. dollars, and Chinese consumption economy is 5.7 trillion U.S. dollars. It's about 40 percent GDP. So if you look at the more developed economies, consumption as a percentage of GDP is 70 percent or above. So China has a lot of room to grow, and we only have 300 million middle class consumers and there's another billion people in China that are improving their lives and improving their incomes every year. When I started at Alibaba 21 years ago, the GDP per capita of China was like, you know, around $900 per person. Now China has a $10,000 GDP per capita, and it's made a lot of strides. There's no reason why that trajectory is not going to continue. So for us being very -- having a very good position in our core market at home and also moving into some of the more developing economies like Southeast Asia, that's our strategy.

ANDREW ROSS SORKIN: But Joe, and this goes to the decoupling issue. TikTok is one specific issue here in the United States, but to have a Huawei on the other end of this is not just an issue in the U.S., it's an issue globally potentially. How do business people in China think about that?

JOSEPH TSAI: Well, there's a variety of views in China, and I think it's always, you know, dangerous to say that -- to go into the motivation of the government, you know, actions against the companies. But from what I could see, the overall concern about national security and all that, that's -- those are concerns that's up to the U.S. government to decide if they want to protect their own citizens. So for us, we are also seeing a trend of various governments that care about data privacy, that care about protecting their consumers within their borders. So when it comes to data, for example, we run a cloud computing business, and we have the state of the art protection in terms of security. We run the most robust security systems I would say in the world, because our business in E-commerce is mission critical. If something fails within our system, if we're hacked or our data gets stolen, it is the end of the world for the company. So for us, these are some of the issues that we're very, very focused on as we expand into other jurisdictions.

ANDREW ROSS SORKIN: Mary, we've made it almost halfway through our conversation without mentioning the phrase "COVID-19," and I'm curious as an investor, especially globally, how you look and whether you even measure the success or failure rates, if you will, and even expectations of how you think governments are going to handle COVID in terms of how you're making recommendations for investing in specific countries.

MARY CALLAHAN ERDOES: Yeah, the country where the company is headquartered, obviously, has a lot to do with how fast return to office happens, what are the economics, and what does the government support, how much are they giving to consumers to be able to sustain themselves during these trying times. And all of that plays into, you know, the global quantitative easing, which is helping everything. And you can see it manifest itself in the public markets around the world. We try to look through that and be able to see where the opportunities are in the less liquid, less government-supported areas, where you hop through, just as Secretary Mnuchin said. As soon as we get to rapid testing and hopefully vaccines, it changes everything. This will end. Countries like China, they've been through this before. They've come out of this much faster and stronger because of their lessons learned from SARS and other things. And I think a lot of countries around the world will have to get up to that same pace of being able to work through these things. But you still find opportunities everywhere, and you have to find the ones that are not necessarily the ones that are the obvious losers today because of restaurants or the like, or winners today because of E-commerce, but really what's going to happen over the long-term. And when you look at these companies and when you're a long-term investor, you have to be able to see that maybe there's things that are opportunities in the real estate markets in Berlin, or maybe there's logistics businesses in Brazil that are important to look at; the loan market, the places where people aren't looking, the less obvious places. And I would also just add that while everybody talks about all the, you know, COVID-related companies that they would like to look at, or the like, sometimes it's important just to look at the boring parts of the portfolio and make sure that those are in place. Because we can have a high increase on some of the things that have participated from a lot of this quantitative easing, and you look at things like the bond market. If you were to invest in the Chinese bond market, you would have a high yield of 3 percent. So those are pretty interesting opportunities. But, you know, the US is still a high-yielding country in the bond market relative to others. So while it's very hard to stomach the yields that are available today, we may be looking back in a year from now and salivating over today's yields, wishing we had put them in the portfolio. So just keeping all of that in balance is really important, and looking through the long-term. And then, you know, the other thing that's just hard to do is, given all the uncertainty in the world with, obviously, COVID-19, but the elections, hard Brexit, etc, people just have to be able to say: Is my portfolio right-sized for another set -- a bout of volatility? And have I trimmed the things that have really had a nice run? And psychology prevents you from naturally doing that. So constantly taking a look and making sure that it's the right way for the long-term is a super important part of our jobs.

ANDREW ROSS SORKIN: John, can you speak to any opportunities that you've seen? Are there industries or areas or countries even right now that you're saying to yourself, you know what? Maybe they're under loved, unloved, or maybe they're basic. We were talking about more basic and boring, as Mary was saying.

JOHN VASKE: One thing I didn't touch on, I should have mentioned earlier, I wear sort of two hats at Temasek. One is the head of the Americas, but also head of our global agribusiness. And I think one area where deglobalization, you know, isn't really possible is in the area of agri and food. And, you know, the fact that we've got a growing population and yet the land mass in terms of variability and the ability to be productive against that isn't increasing, just to state the obvious. So we're seeing a lot of opportunity. You know, COVID struck a little bit of fear and panic in terms of supply chains and things of that nature, but it quickly came back together again. So there's a lot of innovation, a lot of technology, there's a lot of public companies of large scale that we can invest in. So as both a public and private investor, there's lots of different opportunities for us to express a point of view as we see things across the full agri and food value chain. And so, you know, as you go into alternative proteins or plant-based things and other forms of production, there's just ample opportunity, and yet I think a lot of investors are looking at it, but we have found it to be quite an interesting place to look.

ANDREW ROSS SORKIN: John, let me ask you one other question. It relates to what Mary was saying earlier. I want to ask you about debt, actually, which is, as you know, central banks around the world are just printing money left and right. How do you think that ends? Can it end well? Is there a way that this is okay, and therefore how do you even think about the various countries as well?

JOHN VASKE: You know, I wish I knew. I would just echo everything Mary said. We do look at it on a sort of region-by-region basis in that regard in terms of the financial health. But I don't have a great answer in terms of how it ends. It certainly influences the way markets are trading these companies, even in the private market by way of valuation. It's caused us to be probably a little bit conservative and miss out on some things, but it's hard to see when it ends as well. So, I don't have a great answer for you, Andrew, in that regard.

ANDREW ROSS SORKIN: Mary, maybe I'll put the question back to you, how you think about all of this money printing, but also what you think has happened to valuations, not just here in the United States but really around the world. We've obviously seen multiples already expand. Have they expanded too much, too little?

MARY CALLAHAN ERDOES: It's a great question. I'm not sure anybody has the answer. Obviously the first thing that happened was when interest rates were reset and you went -- you know, and you reduced the ten-year treasury down to a mere 65 basis points which we are at today, you naturally reset earnings because you're not discounting them back at a high rate. So you've got an increase naturally of about 15 percent on most companies, if all else was equal and everything was back to where we were in the February time period. But now you've had such runup in so many companies. You know, we were just looking yesterday, the change in market cap in Apple stock is equal to the market cap of the four largest financial institutions in the United States of America. The change is equal to the total market cap. Or if you look at something like Tesla, the Tesla market cap is equal to the market cap of Toyota, Daimler, BMW, VW, Ford and GM altogether. But if you look at the underline -- just take Volkswagen as a for instance, which is one of the holdings in our European focus portfolio. It's got 11 times the R&D and CAPEX of something like Tesla, it's got 11 times the revenues and it's got 30 times the number of cars sold. So one of those two things is mispriced and, you know, a lot of liquidity will jettison some of these areas, and you just have to be able to see through and say: Where is it going? And Joe mentioned Tesla and the growth that it's having in China, so the market is saying that's where it thinks that the opportunities are, but perhaps it's not looking through to all those other companies which are also focused on electric vehicles and the like and continue to see great opportunities there. So a lot of liquidity will do very strange distortions to the market.

ANDREW ROSS SORKIN: Fair enough. I can't let this conversation end without a little bit of discussion about basketball. I should say John, by the way, was a college basketball player at Columbia. But, Joe, I want to get the inside scoop on what it was like both inside the bubble, but more importantly, how do you think about the future, how do you think about next season and what it portends, not just for the NBA, but frankly for the world in terms of live events, bringing people back together and what that timeline in your mind is looking like?

JOSEPH TSAI: Well, first I have to say the Nets did pretty well in the bubble. We didn't advance beyond the first round, but we won a few games especially against the Bucks and the Lakers. But we had an early exit. Unfortunately, I wasn't able to go into the bubble. But the thing about live sports is that a very big part of the economics of the teams comes from having fans in the building. So in the COVID era, with social distancing and people not being able to congregate in a place, that's really going to prevent in the economics. But these are challenges that can be overcome with time because we know, as Mary points out, that there's going to be a vaccine. You can have rapid testing programs before people come into the building. So at some point, that's going to come back to normal. So we're kind of looking at -- obviously we're in the playoffs right now, very excited about the Lakers and the Heat, congratulations to them. And the next season is going to be a little bit tricky, because we don't anticipate having a lot of fans or having full buildings into the arena anytime soon. But guess what? You know, the following season, '2022-23, we look for a very nice rebound. And the thing is, live sports is a rare commodity. You could tell just during the COVID period when there was no sports on TV, people just were craving for it. And once you put the games on, people have come back to watch sports enthusiastically. So I'm very, very positive, very excited about the future of live sports.

ANDREW ROSS SORKIN: Well, I liked the use of the word "rebound." I think we're all rooting for a big rebound across the board. Joe, I want to thank you. Mary and John, thank you as well for a tremendous conversation this morning at Delivering Alpha. Appreciate it very, very much.