IceCap Asset Management commentary for the month of August 2020, titled, “Why we are bearish on Turkey and the Lira.”

Q2 2020 hedge fund letters, conferences and more

Turkey And The Lira - Introduction

IceCap Asset Management Ltd. believes there is a high probability of Turkey experiencing a severe crisis within its currency, equity, and fixed income markets. Most global investors are unaware of this developing crisis, and those who are aware of this crisis may not appreciate the knock-on effects that could develop. The emerging crisis in Turkey is important for all investors as it has the potential to spread to other currencies, equities, and bond markets.

During the past few months, we have been expecting the Turkish economy and the Lira to experience significant stress due to the following:

- Economic issues including severe current account deficits and negative real interest rates

- Supply/demand mismatch with USD

- Weak banking system

- Unorthodox monetary policies

- Geopolitics, and the unlikelihood of receiving a significant swap line from a major central bank

Turkey experienced a severe economic and currency crisis in 2018 that still has lingering effects today. The current coronavirus pandemic has caused Turkish exports to grind to a halt and tourism to all but disappear, yet Turkey still must import the vast majority of its energy resources causing deep current account deficits. Turkey has been experiencing high inflation for years now, currently at around 12%. President Erdoğan has demonstrated his reluctance to raise interest rates, holding them at around 8.25%, causing negative real rates of approximately -3.75%. This discourages foreign capital from entering the country. All these factors paint a dire economic picture for Turkey’s economy.

Turkey needs USD to participate in trade and repay its substantial borrowings that are soon coming due. At the same time, it needs to sell USD in order defend the Lira. Our concerns regarding the Turkish economy and the Lira is driven by the fact that Turkey is rapidly burning through its foreign exchange reserves and is likely to run out of USD soon. It is far from certain, and perhaps even unlikely, that the United States will provide Turkey with a swap line, and even if they do this will not solve the underlying problems and will only delay the inevitable.

The Turkish banking sector has also been weakening. There is evidence that the Turkish Central Bank has been using the commercial banks as a source of foreign currency for defending the Lira. This withdraws liquidity from the system. There is also the potential for capital flight as the economic situation worsens. Meanwhile, the banks have still not fully recovered from the 2018 crisis and are holding a large amount of non-performing loans as a result. Turkey is already under significant economic stress, and the last thing that they need is a systemic banking crisis.

President Erdoğan has taken control of most facets of the Turkish government, including the central bank. He has appointed his son-in-law, Berat Albayrak, as Minister of Finance and Treasury. Both men have been criticized for their unorthodox economic views, including an intense reluctance to raise interest rates, instead preferring to pursue economic expansion and loose monetary policy at all costs. These policies are likely to exacerbate the coming crisis.

Turkey sits on a major geopolitical fault line. It is heavily involved in proxy wars in Syria and Libya, has frequent border and energy claims disputes with neighbours in the Eastern Mediterranean, and will likely have competing energy claims disputes with its neighbours in the Black Sea in the near future. Turkish geopolitics are incredibly complex, and Turkey often finds itself on the same side as one of its allies in one proxy war, but on an opposing side in another. While geopolitics is not a direct cause of the looming crisis, it does have the potential to be a trigger. Geopolitics will also have to be considered when evaluating potential solutions to the looming crisis, including swap lines and bailouts which are, of course, political in nature. Turkey’s current geopolitical footing makes the risk of a geopolitical dispute triggering a crisis quite high, while also reducing the probability of Turkey receiving financial assistance from a foreign power.

Many investors are beginning to become aware of the expected crisis in Turkey, but few understand its root causes and what the crisis may mean for their portfolio. We have seen some articles state that Turkey is a one-off case and should be treated differently than other emerging markets. However, we know that emerging market crises tend to cause contagion and have the potential to spread to other emerging markets. We also know that European commercial banks remain overly exposed to the Turkish economy and are therefore vulnerable to the expected crisis. We saw a crisis with some similarities to Turkey play out in Lebanon recently, meaning that Turkey is not the first emerging market economy to experience significant stress under the current conditions, and it is unlikely to be the last. It is important that investors understand their exposure to Turkey and manage their risk accordingly.

This paper seeks to explain the causes and potential outcomes of the looming crisis in Turkey, and IceCap’s views on how we expect the crisis to unfold. We also seek to inform readers and investors of the possible knock-on effects that a Turkish crisis will cause.

Overview of Turkey

Turkey is positioned on the border of Europe and Asia. This has always made it a place of geopolitical significance, and a major trade route. Turkey has a population of approximately 84 million and boasts one of the world’s great cities, Istanbul. Its capital is Ankara.

Figure 1. Map showing Turkey's location on the border of Europe and Asia. Also, it is right between the strategically important Black Sea and Eastern Mediterranean.

Since the end of the Ottoman Empire, Turkey has been a secular, unitary parliamentary republic. This has shifted under President Erdoğan who brought the country into a presidential system in 2018. He has also enacted more Islamist policies, recently turning the Hagia Sophia into a mosque. The former museum/church was built in 537 AD and has great significance to Christians.

Erdoğan’s Justice and Development Party (AKP) has recently been losing support in major cities such as Istanbul, Ankara, and Izmir, but remains popular in more rural areas. Erdoğan has been consolidating power in Turkey since he took power in 2002, although he accelerated his authoritarian leanings after the alleged coup attempt in 2016. Erdoğan and the AKP party blame Pennsylvania based cleric Fethullah Gülen for the coup attempt.

Turkey is considered to be an emerging market economy. It has the second largest military in NATO and is a member of the United Nations, Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development, G20, International Monetary Fund (IMF) and World Bank. Turkey has been trying to gain European Union (EU) membership for over a decade now, although it is in a customs union with the EU. Its largest economic sectors are agriculture and textiles, although more foreign businesses are setting up manufacturing in Turkey to take advantage of a weak Lira. Tourism has been growing in Turkey over the past couple of years, but the coronavirus pandemic has devastated tourism in 2020. Turkey does produce some oil and natural gas but is far from self-sufficient. This has caused them to run large and frequent current account deficits.

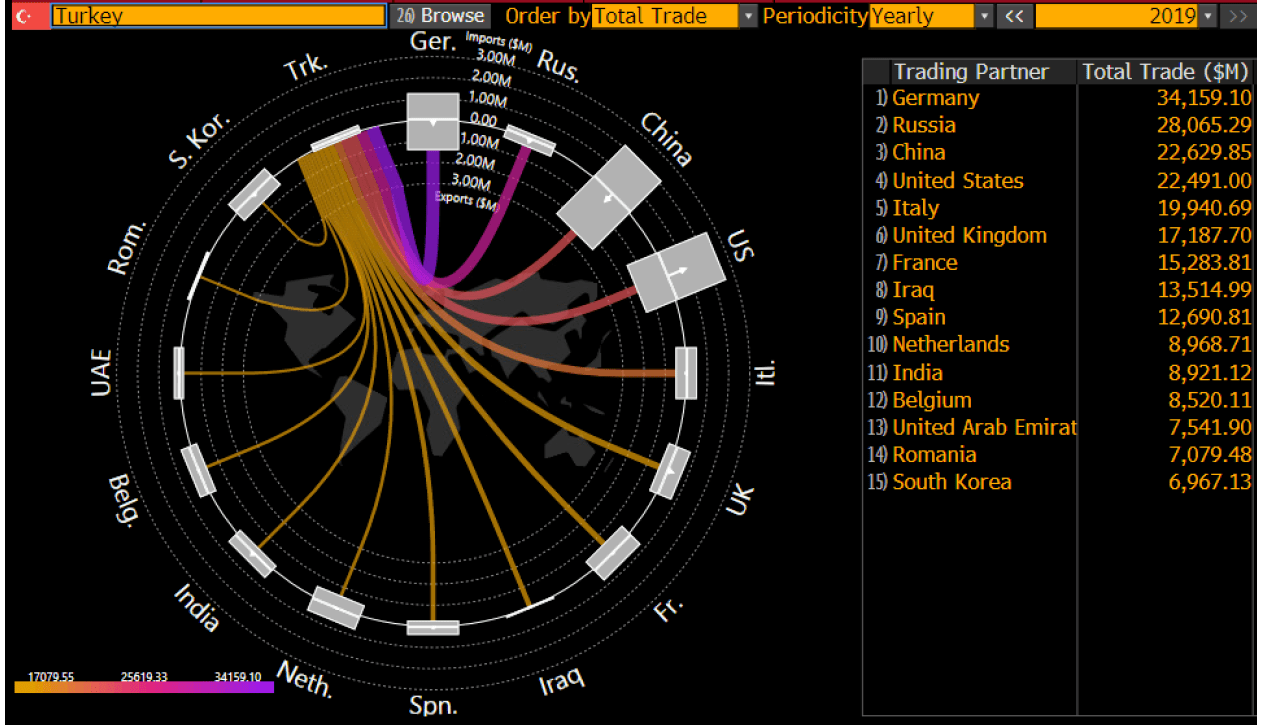

After experiencing a period of extended growth after the 2008 Great Financial Crisis (GFC), Turkey had a currency and debt crisis in 2018, the effects of which are still being felt. During the period of economic growth Turkish companies borrowed heavily in foreign currencies, much of which is coming due in 2020 and 2021. Inflation is around 12% in 2020 and the economy is expected to contract by 4.3% in 2020.2 Turkey’s largest trading partner is Germany and its complete trade flows are as follows:

Figure 2. Turkey's Trading Partners. Germany benefits from an EU Customs Union with Turkey. Russia is significant as an oil and gas supplier.3

The Turkish Economy

The Turkish economy has been under significant stress for a couple of months now. Most notably, it has high inflation, negative real interest rates, and severe current account deficits. Some of these problems are structural in nature while others have been brought on by the coronavirus pandemic. Regardless of the cause, the Turkish economy is in real trouble and this will have major implications for currency, debt, and equity markets, in Turkey and abroad.

Current Account Deficits

A nation’s current account can be thought of as a country’s income statement. A positive current account means the value of a country’s revenues from exports are greater than the value of the country’s expenses from its imports. A negative current account means the country is spending more money than is coming in.

Turkey, like many emerging market economies, is an export driven economy. Foreign companies, mainly from the European Union, which is in a customs union with Turkey, have been investing in manufacturing in Turkey since the 2008 Global Financial Crisis (GFC). This was done to take advantage of a credit boom, loose monetary and fiscal policy, and a weak Lira. Turkey is also a major exporter of agricultural products and textiles. Another crucial sector to the Turkish economy is tourism which has also benefited from a weak Lira over the past few years. When economic times are good, trade is flowing, and people are taking vacations to Turkey. Currently economic times are not good. The coronavirus crisis has caused a steep reduction in global Gross Domestic Product (GDP) and trade has declined dramatically. Furthermore, travel restrictions due to the virus have almost eliminated tourism dollars flowing into the Turkish economy. Therefore, there is less money flowing into Turkey’s current account.

When a country imports goods from other countries, this represents an outflow from the current account. Turkey does not have a major domestic source of energy, meaning that it must import nearly all its energy needs from other countries. Turkey imports 85% of its oil and gas in its energy mix.4 In 2019, energy imports totaled $41.48 Billion making up approximately 20% of total imports.5 It is also worth noting that commodity prices are settled in USD, so a strengthening USD will only exacerbate this issue. While the inflows from tourism and trade that help to reduce the current account deficit have been largely eliminated by the economic fallout from the coronavirus, the demand for energy imports that increase the current deficit has mostly remained.

On August 19, 2020, Turkish officials announced that they would deliver some good news to Turks. On August 21, 2020, Turkey announced that it has found large natural gas reserves in the Black Sea. Because a key consideration of this paper is the energy driven current account deficit, the paper would be incomplete without dealing with this announcement. Considering the combined financial and economic stress, we find it difficult to accept this as fact. Turkey and the Lira are on the verge of collapse and this announcement seems to be a little too convenient. The market seems to agree, showing a quick appreciation of the Lira upon the pre-announcement followed shortly by a reversion back to a soft peg at 7.3, in a “buy the rumour sell the news” pattern. Then upon the official announcement with the discovery details, note how the Lira again sold off on the news.

Figure 3. Turkish Lira price chart on August 19th, the date that Turkey announced it would be delivering "good news" to the Turkish people. It was widely speculated that natural gas was discovered in the Black Sea. The Lira quickly appreciated, and then quickly reverted. Note that this chart is inverted, meaning that when the white line goes down the value of the Lira goes up, and vice versa.

See the full report here.