Excerpt from Whitney Tilson‘s book, The Rise and Fall of Kase Capital, discussing Claire’s stock from How to Avoid Getting ‘Faked Out’ By a Company’s Management.

Q2 2020 hedge fund letters, conferences and more

I'm almost finished with my new book, The Rise and Fall of Kase Capital, which I hope will be out by the end of the year. Here's the current draft cover:

How to Avoid Getting 'Faked Out' By a Company's Management

My friend and hedge-fund manager Mohnish Pabrai – who famously paid $650,000 to have lunch with Warren Buffett years ago – has an interesting policy...

He never speaks with a company's management. His rationale is that he thinks that if he did, he could get fooled.

He's right to be concerned...

Most CEOs are charming, charismatic, and persuasive. And they almost always genuinely believe that the future of their company is so bright that they need to wear sunglasses. Even the honest ones are so emotionally and financially committed to their own company that they're often the last people to see that the business is falling apart.

As a result, they'll look you in the eye and tell you that their mall-based retailer, check-printer, or newspaper – pick your dying business – is going to turn around... largely due, of course, to all of the clever things they're doing.

It's even more dangerous if you develop a personal relationship with a CEO and like him or her as a person. A good warning sign is if you hear an investor talk about the CEO using his or her first name.

Some of my biggest investing mistakes have happened when I got to know a CEO personally and became blinded to the fact that the company and/or its stock was going down the toilet.

One of the first big losses of my career happened with a company called Visible Genetics...

It had developed a blood test to tell doctors which "cocktail" of drugs would effectively treat AIDS patients. It drew me in for a number of reasons: It had cool, cutting-edge technology... It was addressing a major health care crisis and had the potential to save lives... And through a friend, I had gotten to know the CEO, which made me feel like I had an informational edge.

My relationship blinded me to the fact that this was a single-product diagnostic-test company, competing against giants like LabCorp (LH) and Quest Diagnostics (DGX)... and that Visible Genetics' income statement, balance sheet, and cash flow statement all showed that the company was in serious trouble, generating minimal revenue and burning through large amounts of cash.

Sure enough, the stock collapsed and I rode it all the way down from $12 a share to $1.

The Case of Claire's

Similarly, talking with management can fake you out of buying its stock. This is exactly what happened to me in the case of Claire's...

The mall-based retailer sold various accessories like hair scrunchies and cheap jewelry to young girls who loved shopping at Claire's (all three of my daughters included). The company had been around for decades.

Founder Rowland Schaefer ran it for decades and was a great operator. He kept costs low, always had fresh, exciting products, and had his finger on the pulse of what young women liked to buy. Claire's always had strong growth, margins, and returns on capital.

In early 2003, leading up to the Iraq War, oil prices spiked as investors feared that bloodshed in the Middle East would disrupt oil supplies. That uncertainty caused the entire retail sector to get clobbered due to general macroeconomic concerns that later proved to be ill-founded. I bought several retail and fast-food restaurant stocks at the time and ended up making a fortune.

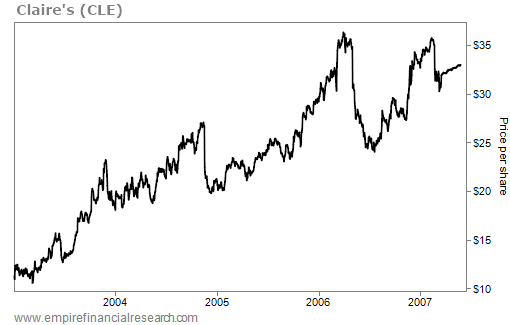

Claire's got caught up in the downturn. Its stock had sold off, so I did my research on it, concluded that it was significantly undervalued, and was about to buy shares...

Just before doing so, however, I learned that one of Schaefer's two daughters – who had recently become co-CEOs after their father's stroke – was going to be in New York. She was taking meetings with investors and prospective investors, so I reserved a meeting with her.

After our hourlong chat, I came away very unimpressed. It was clear to me that she had gotten her position simply because she was the founder's daughter.

It totally deterred me from buying the stock, and I ended up missing out on an easy double. (In 2007, the company was bought out by a private-equity firm for $33 a share... up more than 200% from where it was trading a few years earlier.)

In the case of Claire's, I didn't get faked out because of a charming, charismatic executive. Rather, it was due to a vivid data point that later turned out to be trivial. While Schaefer's daughter and her sister had the titles of co-CEO, their father was the one making the key decisions behind the company.

Having shared these two anecdotes, you might think that I share Mohnish's opinion to never meet management. But I don't. The answer is more nuanced than that...

I've owned shares of Microsoft (MSFT) on and off over the years, but I've never felt the need to meet founder Bill Gates, former CEO Steve Ballmer, or current CEO Satya Nadella. I can assess them via their appearances on television or YouTube if I want... Plus, I'm more focused on things like their business, competitive threats, regulation, etc.

In the case of large-cap companies, if you aren't a multibillion-dollar hedge fund, you won't have access to those guys, anyway.

But it's a different story when it comes to small companies... Most of them are small for a reason – because their businesses generally aren't as good as a Microsoft or Berkshire Hathaway (BRK-B), nor can they afford a world-class CEO. Therefore, the quality of management is both more variable and more important in determining the performance of their business. Thus, I find that meeting with management is valuable when I'm evaluating these small companies.

Of course, most individual investors don't have the opportunity to meet and speak with management of publicly traded companies – even small ones. But fear not! There are plenty of ways to get to know management without meeting them in person...

The first thing I'd recommend is to read the CEO's annual letters to shareholders for as many years as possible. Then, listen to or read the transcripts of the company's conference calls. You'll get a sense of how management thinks about its business and its opportunities.

Plus, with the benefit of hindsight, you can see whether the decisions these folks made – making an acquisition, expanding into a new market, buying back stock, etc. – worked out well for shareholders. You'll get a good sense of whether they're honest, trustworthy, and care about shareholders.

It's hard to make those kinds of judgments by just looking at the numbers, so you need to go a little deeper.

My word of caution – particularly to inexperienced investors – is to go in with a skeptical view of management. Again, these people are skilled, highly incentivized salespeople, and they aren't necessarily lying... When I look back at when I've gotten burned believing CEOs, nine times out of 10 they fully believed what they were saying.

To accurately evaluate a CEO, sometimes you need to be a really good judge of character and pick up on little clues. But often, the truth is slapping you in the face...

Consider Angelo Mozilo, the former CEO and chairman of mortgage lender Countrywide Financial. He came in with the perfect tan, bleached teeth, wearing diamond-encrusted jewelry. One look at him and he just screamed "con man" or "used-car salesman." It came as little surprise when he got charged with insider trading and securities fraud a few years later.

Another example... I remember Buffett and Charlie Munger joking at a Berkshire Hathaway annual meeting years ago that you didn't have to be a rocket scientist to figure out that the late publisher Robert Maxwell was a crook.

In 1991, Maxwell died under mysterious circumstances off his yacht. Shortly thereafter, news surfaced that he had looted his employees' pension plans. Buffett and Munger said, "For heaven's sake, the guy's nickname was 'The Bouncing Czech'!" (a play on words, reflecting not only a bad check, but also because he was originally from Czechoslovakia).

Other times, however, total crooks will be incredibly polished and make a great impression. Former Enron executives Ken Lay and Jeff Skilling went to Harvard Business School. They claimed to be revolutionizing an industry and people ate it up.

Interestingly, sometimes management can be compelling for the opposite reason, too...

Mike Pearson, the former Valeant Pharmaceuticals CEO, was the dumpiest looking guy you've ever seen, but that was part of his appeal. After reading William Thorndike Jr.'s book The Outsiders – which profiles eight different brilliant CEOs who shook up different industries by being iconoclasts – many brilliant investors, including my friend Bill Ackman, got sucked into Pearson's web. Bill famously lost nearly $4 billion on that trade.

One of the reasons Buffett is known as one of the greatest investors of all time is not only because he's a great capital allocator, but he's also a great judge of character. He does an incredible job of managing the CEOs of the 75-plus operating businesses that Berkshire has purchased over the years.

These folks come from every corner of the world... every personality type... are motivated by different things... and are running totally different businesses. But almost uniformly, they love working for Buffett and would run through a brick wall for him.

Buffett has done an excellent job of finding great people and avoiding turkeys. His skill in this area doesn't come primarily from special access (though he certainly has it).

Rather, he keeps it simple and looks for only three things: smarts, work ethic, and integrity – and never compromises. If he has any doubts about someone in any of these three areas, he simply moves on – and you should, too.

Best regards,

Whitney