Chris Scibelli, Managing Director for ACR Alpine Capital Research, discusses “inflation plus five percent.”

Q2 2020 hedge fund letters, conferences and more

As yields have declined and equity valuations have climbed, consensus expectations for future capital market returns have dissipated. As such, the minimum essential hurdle most asset owners must exceed has become a perilous mountain trek.

From today’s base camp, the mountain sometimes known as "Inflation plus five percent" looks almost insurmountable. Even Sir Edmund Hillary might balk at such an outlandish expedition.

This article focuses on the public equities portion of an overall asset allocation. It refrains from a discussion of fixed income, credit and alternative investment allocations.

When constructing public-equity exposure, modern-day asset owners have typically relied on benchmark-driven, relative-return implementation methods. Such as:

- Actively managed public-equity strategies that promise the return of the benchmark plus a suitable margin (alpha) over said benchmark.

- Passively managed public-equity strategies that promise the return of the benchmark.

Tautologically, the ex post absolute return that an asset owner will ultimately receive from the public-equity component of his/her asset allocation, is derived without ex ante regard for the asset owner’s minimum return requirements or liabilities.

Inflation Plus Five Percent: An Unpalatable Recipe

This phenomenon is an unpalatable recipe when public-equity benchmark returns are expected to be de minimis—and forecast to be less than "inflation plus five percent."

Today, if consensus thinking expects the future returns of public-equity benchmarks to be insufficient relative to "inflation plus five percent", then standard passive and active equity strategies will fail to deliver the necessary results, and public equities will be an untenable anchor in the asset owner’s overall portfolio. As the saying goes, “You can’t eat relative returns.”

The capital markets have generally experienced a tailwind since the early 1980s. In August 1982, T-bill yields were in the mid-teens and a long-dead bull market in equities sprung to life. With a few notable exceptions, since then interest rates have trended lower and publicly traded equities have trended higher. About that time the investment industry began to steadily—if not arbitrarily—carve up and segment portfolio management into a smorgasbord of impressive sounding sub-options (large-cap, mid-cap, smid-cap, small-cap, micro-cap, growth, value, international, global, emerging markets, frontier markets, etc.). These subcategories somehow calcified into rigid asset classes, to which many CIOs feel beholden.

Liabilities Not Benchmarks

Until then, balanced managers had been the original unconstrained absolute return investors, decades before Absolute Return and Unconstrained Investing became Defined Terms with Upper-Case lettering. Balanced managers had the investment freedom to deploy public-equity capital broadly and judiciously as they determined where attractive opportunities could be found. Back then portfolio managers strived to compound their investors’ capital at reasonable rates to help them fund their liabilities. There was no obeisance to an arbitrary benchmark and no kissing of the ring of style-box orthodoxy.

The eventual introduction of style-boxes, peer groups, various new indexes and new investment products further segmented the public-equity universe by market capitalization, geography, and/or style (growth, value, GARP). The technological innovation of easily accessible database peer group comparisons first on your desktop and then on your handheld device further hastened the trend of segmenting the public-equity universe into sub-segments. Finally, the industry’s imposition of "fully invested" strictures and the introduction of “long/short” and “long-only” terminology obscured the simple virtues of, and tempered the appetite for, old school investing. Unwittingly, these industry innovations ultimately reduced the opportunity set and restricted the active management of long-only public-equity portfolios.

By adopting a style-box, benchmark-sensitive public-equity approach, asset owners disconnected their public-equity assets from liabilities—one being tied to relative returns and one absolute. Asset owners locked their public-equity allocations into a relative game, while relegating absolute returns to higher fee, Upper-Case worthy alternatives and hedge funds, but the nature of asset owners’ liabilities has not changed.

Solving A Math Problem

With yields near all-time lows and with equity valuations stretching (arguably distorting) the returns of various benchmarks, the future returns from benchmark-driven public-equity strategies are widely expected to be subdued. Yet public equities are an essential component of any asset allocation—often comprising 30-50%.

The math problem facing asset owners is how to maximize the return potential from their public-equity sleeve without increasing the risk profile of the sleeve and overall portfolio.

- Why not explore non-conforming, non-classical, non-traditional, actively managed public-equity strategies that are designed to deliver satisfactory absolute returns which are measured against the asset owner’s minimum return requirements or liabilities.

- Public-equity strategies that employ a private-equity ethos, with a limited number of public-equity investments, each one individually underwritten with a compelling ex ante expected return - while deliberately disregarding a holding’s weighting in a benchmark.

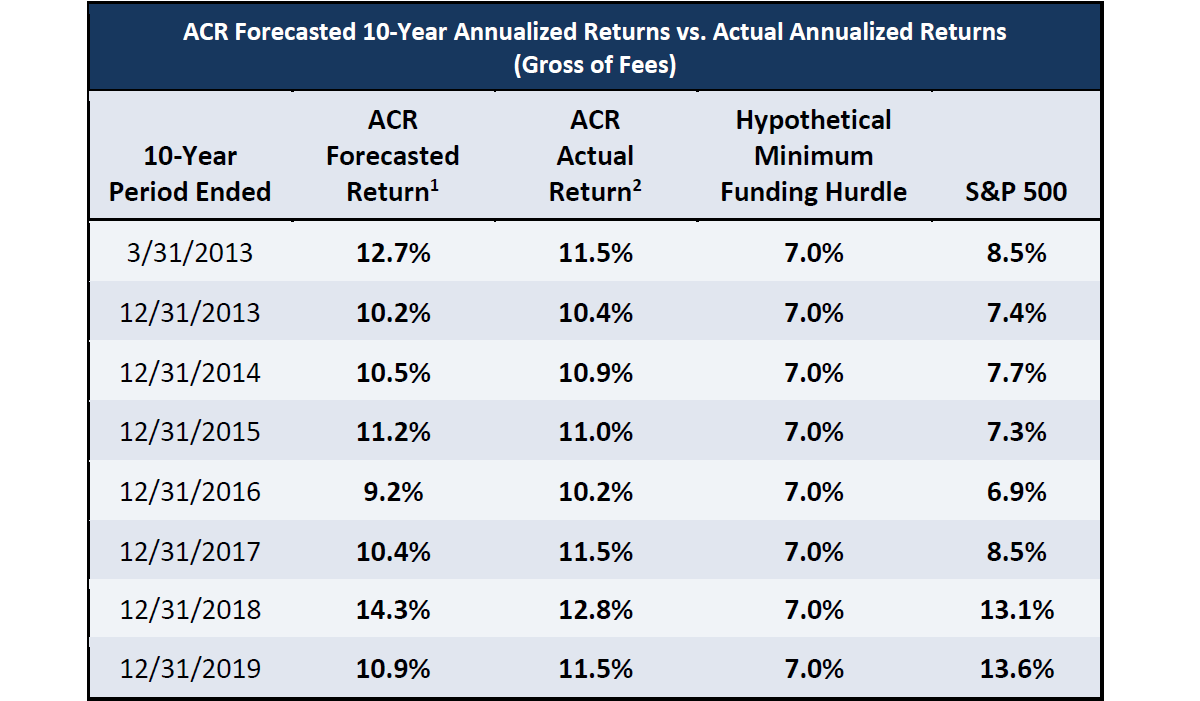

- Public-equity strategies whose success is measured by the accuracy of their ex post actual results as compared to their ex ante forecast.

Numerous financial institutions are expecting public-equity benchmarks to deliver mid to low-single digit returns over the coming decade. If these forecasts are even moderately accurate, asset owners will have a challenging time exceeding their minimum hurdle rates and funding their liabilities. Perhaps it’s time to supplement oft-used benchmark-oriented public-equity approaches with long-tenured public-equity strategies that build a portfolio of concentrated investments that strive for spendable absolute returns.