One of the most flexible and powerful gifting techniques is to loan money to other family members, especially in a period of low interest rates. The reason it works is simple: on average, the person receiving the intra-family loan should be able to invest the money received in a way that produces a rate of return greater than the interest rate on the loan. Thus, when the borrower returns the loaned money at the end of the loan’s term, he will be able to keep this excess return. Because the money was loaned, and not gifted, this excess is tax-free, and you have managed to transfer property to the borrower without paying gift tax.

Q4 2019 hedge fund letters, conferences and more

What Is The Interest Rate On The Intra-Family Loan?

Once, it was possible for you to make an intra-family loan without charging any interest. Ultimately, however Congress decided that this was too good a deal, and passed laws to force family loans to look more like commercial loans. The IRS now divides loans into three durations based on their term: short (less than 3 years), mid (3-9 years), and long (more than 9 years). An “applicable federal rate” is published each month, setting the interest rate for each of the three durations. Most intra-family loans use the mid-term rate, and are nine years in duration, but the best structure obviously depends on the interest rates for that month and other family issues (such as when the lender needs to be repaid for his own cash flow issues).

Who Should Be The Borrower?

The most straightforward way to loan money is simply to extend the loan directly to the family member who needs it. For larger loans, however, some will make the loan to a family trust, instead of directly to an individual. In addition to some income tax advantages (discussed below), this has two principal benefits: (1) it allows parents greater control over the funds that are loaned, and (2) it allows greater flexibility in retaining access to the funds.

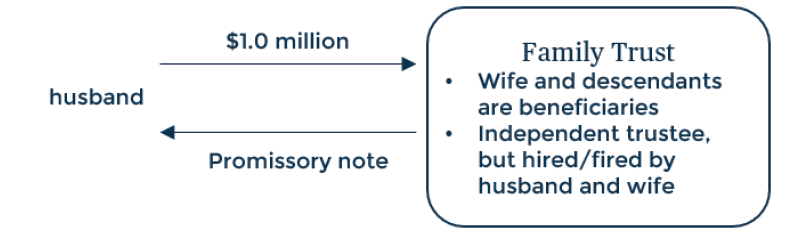

Consider the example depicted below:

Husband loans the trust $1.0 million for a term of nine years, which the trust presumably invests (in securities, real estate, a family business, etc.). The trust owes this money to husband, and must make regular payments on the note. By the end of the nine-year term, husband has been returned all his original $1.0 million. Any property left in the trust, however, gets the following benefits:

- Flexibility: the trust property can be distributed to anyof the beneficiaries, in any proportion. Because wife is abeneficiary, she could receive 100% of the trust property ifthe trustee so decides.

- Tax savings: while it remains in the trust, the trust propertywill not be subject to estate tax in any family member’sestate (not husband, wife, or any descendants).

- Control: the trust can specify how the money is to bedistributed to descendants. In addition, the parents havea great deal of power over the trustee, and can fire himwithout cause.

- Creditor protection: the trust should not be subject toattack by any family member’s creditors, including adivorcing spouse of a descendant.

Income Tax Consequences

The income tax consequences of an intra-family loan depend on who the borrower is. If the borrower is an individual, then the interest on the loan is income to the lender. The interest may or may not be deductible to the borrower, depending on the purpose of the loan.

If the loan is to a trust, however, there may not be an income tax consequence. If the trust is a so-called “grantor trust” (as the family trust shown above would be), then the trust is considered to be the same tax entity as its creator. This means that the loan produces no income tax impact at all, because the lender and borrower are using the same tax ID number and filing the same return.

Risks With Intra-Family Loans

It is very important that all loan formalities be respected and the debt be paid. It must be properly documented with a promissory note, and payments should be made according to its terms. To that end, it is also important that the borrower have the ability to repay the loan. For example, if the loan is to a trust, it would be advisable to ensure that the trust has other assets, in addition to the funds being loaned.

Many experts suggest at least a 10% cushion in the trust, which could be added by gift or accomplished by using a pre-existing trust that had previously been funded. These steps that carefully establish that this loan is “real” should help avoid the primary gift tax risk: that the IRS will conclude the loan was really a disguised gift, and that the entire loaned amount should be taxed immediately (which may result in a tax of up to 50% of the loan).

The other principal risk of the technique is an investment risk. The loan must be paid back regardless of the performance of the loaned funds. If these decline in value (e.g., they are invested in a building and there is an uninsured fire on the premises), the borrower must still somehow pay back the loan. If the loan is forgiven, this will be a gift and subject to gift tax.

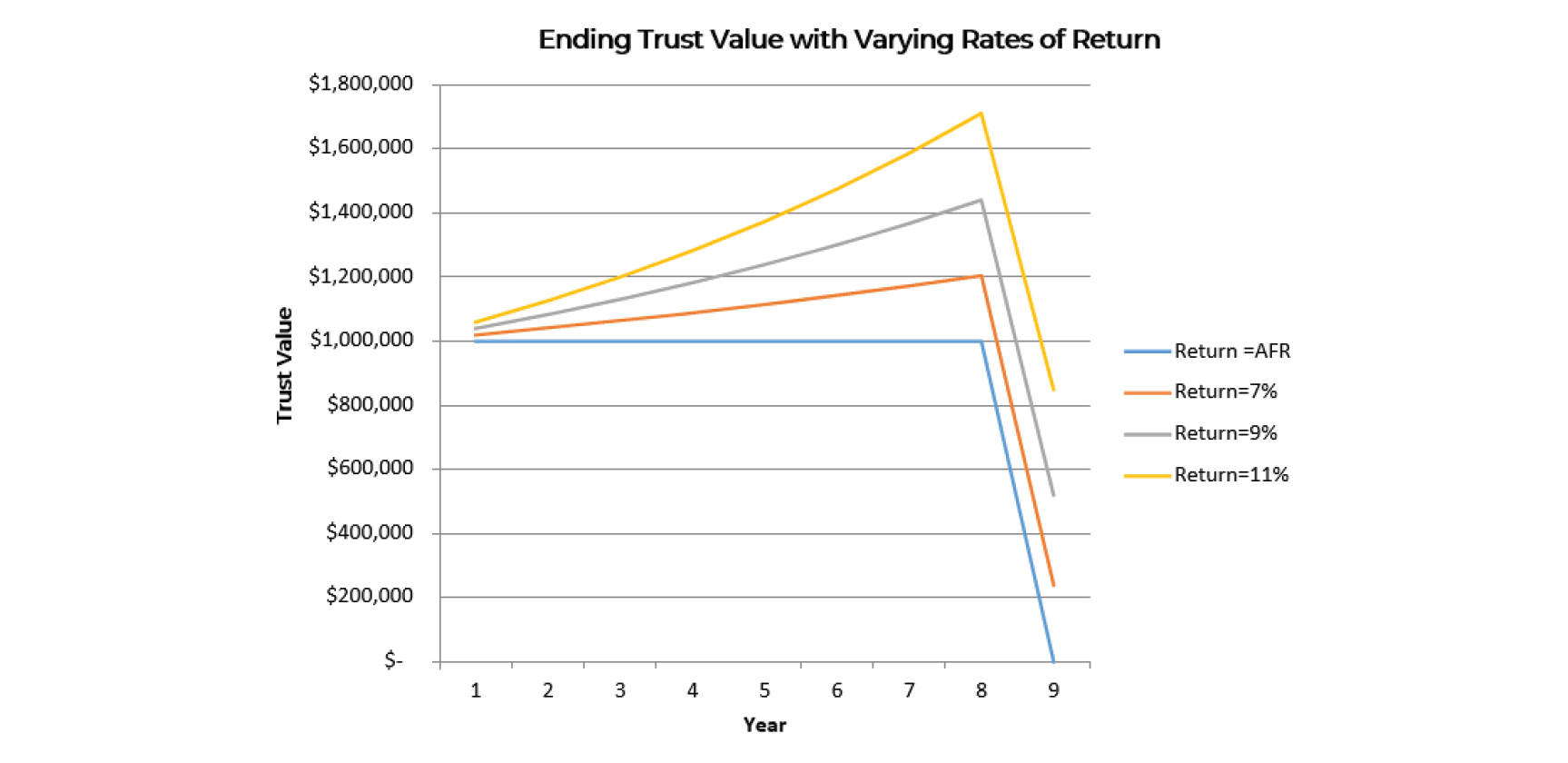

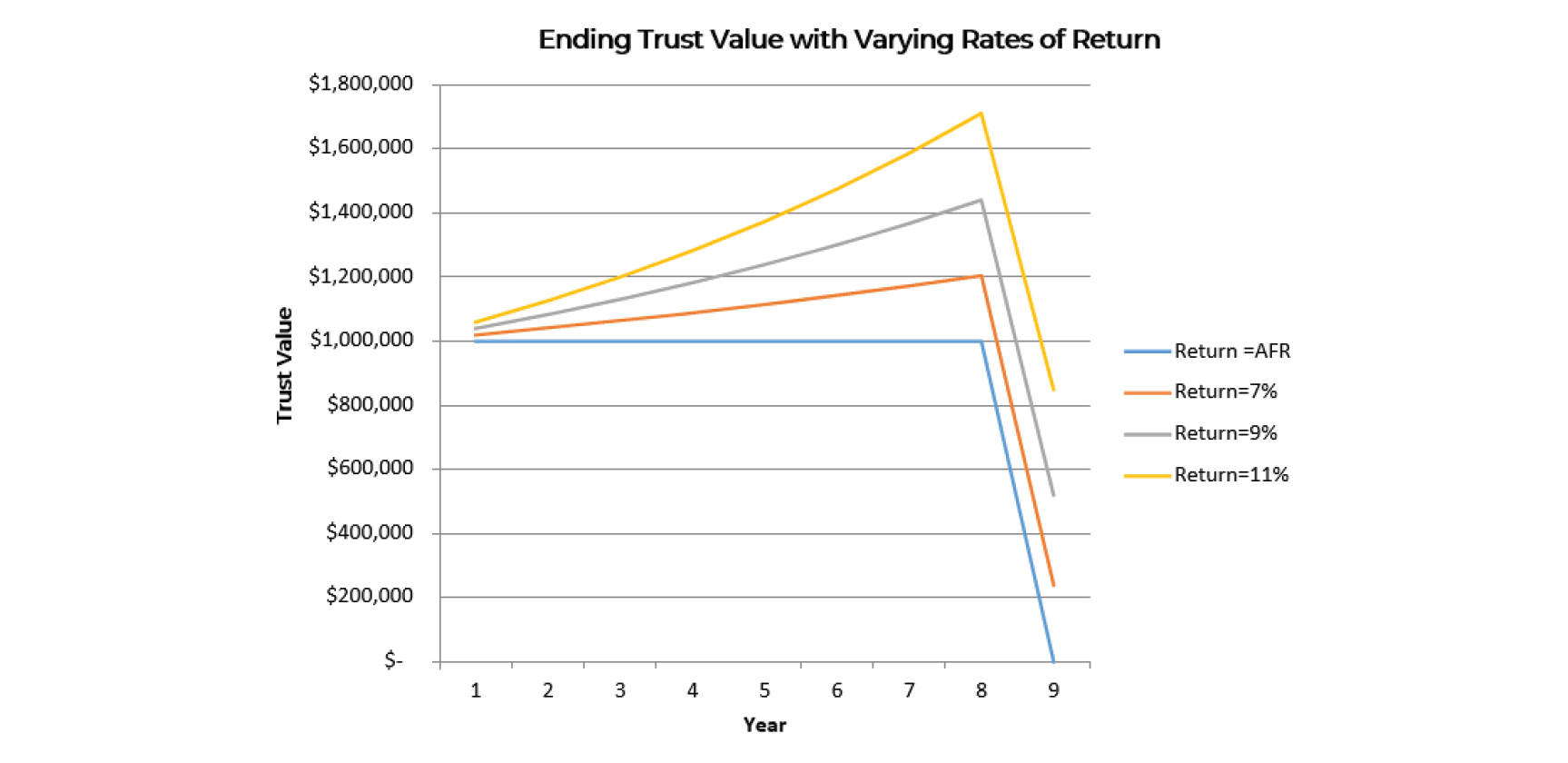

Illustration Of Intra-Family Loan

The technique’s effectiveness is entirely dependent on the return on the invested funds. The following chart assumes a nine-year loan of $1.0 million. The loan provides for annual interest-only payments with a balloon payment at the end of the nine-year term, and funded in a month in which the applicable federal mid-term rate is 5%. The chart attached shows the way investment performance drives the technique: at higher returns, the power of compounding transfers more than 80% of the original loan amount tax-free, while a 5% return produces no benefit at all.

Article by Nicole R. Hart, J.D., Senior Vice President, Trusts & Estates