“The correct lesson to learn from surprises is that the world is surprising.” —Daniel Kahneman

Poor track record of economists at predicting recessions

It has been extensively documented that we humans tend to be poor forecasters. Prakash Loungani and Hites Ahir analyzed the record of economists at predicting recessions in the wake of the Great Financial Crisis. Of the 77 countries considered for the analysis, 49 were in recession in 2009. However, if you relied on economic consensus[1] to gauge the extent of upcoming troubles, you would have been completely oblivious to the upcoming recessionary environment. Indeed, as of April 2008, the consensus expectation was that not a single one of these countries will be in recession. Even more surprisingly, when Loungani extended the deadline for forecasting a recession to September 2008, the consensus still remained that not a single economy will fall in recession in 2009.

Q3 2019 hedge fund letters, conferences and more

Some of us might hold the view idea that economists at prestigious organizations such as the IMF or the OECD likely fair better than their private sector counterparts or vice versa. The research poured cold water on any such idea. What they found is that predictions by the private sector have been just as bad as by organizations such as the IMF and OECD.

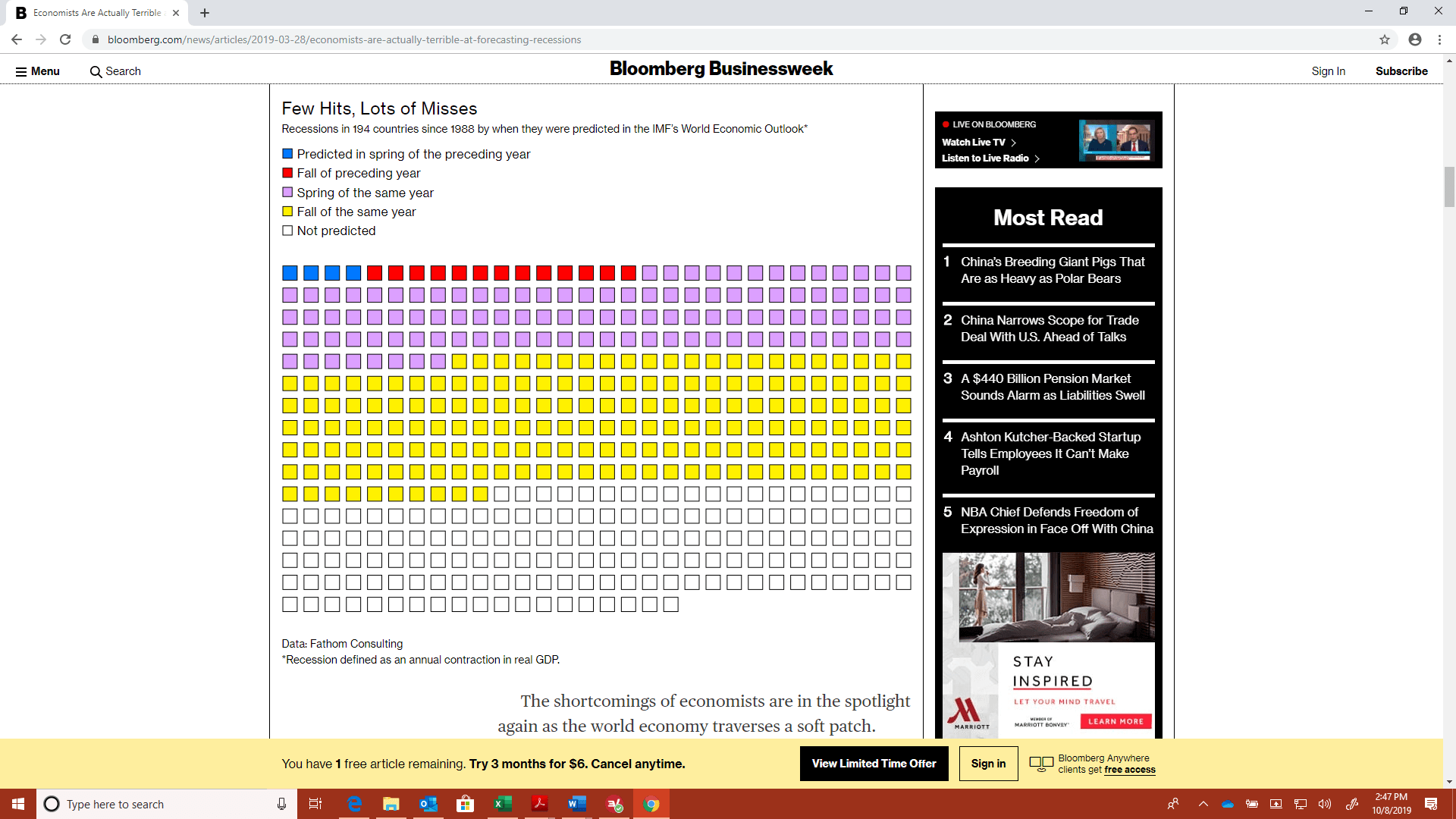

In a recent paper that was published in 2018, Zidong An, Joao Tovar Jalles, and Prakash Loungani found that of the 153 recessions experienced in 63 countries between 1992 and 2014, only five were predicted by a consensus of private sector economists by the April of the preceding year. As is seen in the chart below, economists were woefully poor at predicting recessions even by the spring of the same year.

Source: Bloomberg[2]

Indian stock analysts are an overoptimistic lot

Indian analysts and economists have been found to be similarly fallible. In a research note published in August 2019, analysts at Emkay Global warned investors of the need to be wary of optimistic analyst forecasts. As per the researchers at Emkay, analysts have a poor track record of forecasting earnings for the top 50 companies in India. Indeed, consensus estimates for top-50 companies in India were revised lower in 11 of the past 14 years.

Clearly, such a finding doesn’t just suggest that analysts are poor at forecasting corporate earnings. It further raises the likelihood that equity analysts are an overoptimistic bunch.

India’s GDP growth revisions

Over the past two years, economic trends for India have continued to moderate. Since 2017, we have highlighted that Indian economic growth wasn’t on as sound a footing. Via our quarterly letters for India Moats Fund, we have shared our observations that capital expenditures were continuing to lag and that corporate earnings continued to be disappointing. However, much as Loungani and Ahir found when analyzing economic consensus around the time GFC was unfolding, policymakers, economists, and large swathe of market participants failed to consider such warning signs. Instead, they chose to stay in the la-la land and drum up the narrative that India continues to be the strongest growing major economy.

Of course, reality has its own way reinforcing itself. Persistently disappointing economic growth is forcing the forecasters to lower their forecasts. Having had to lower their GDP growth estimates throughout the year, the RBI at its October 2019 MPC meeting, cut India’s GDP growth forecast for 2019-20 to 6.1%; a rather sharp downward adjustment of 80 basis points from their previous forecast just two months ago. The chart below shows RBI’s GDP growth projection for 2019-20 between February and October of this year.

Source: Business Standard[3]

The corporate tax rate cuts

Recognizing the economic slowdown, the Finance Minister announced a surprise corporate tax rate cut in September, in a bid to revive economic growth. The corporate tax rate was reduced from 30% to 22%. The effective corporate tax rates for domestic companies including surcharges will drop from 34.9% to 25.2%. Additionally, new manufacturing companies formed from October 1 onwards will attract an effective tax rate of 17%.

The tax rate cuts are intended to provide a boost to the flailing economy and attract new capital investments in the manufacturing sector. Equity markets responded enthusiastically to the policy action with the Nifty 50 Index rising by 8.4%, NIFTY 500 Index rising by 8.2%, and the NIFTY Bank Index rising by 14.2% over a two-day period.

The reaction of equity market participants was likely driven by expectations that the benefits of tax rate cuts will be retained by corporates, leading to higher profits; an expectation that was quickly validated by earning estimate revisions by analysts.

Who benefits from corporate tax rate reductions?

When we think of the tax rate cuts and who will benefit from them, we do not find the answers to be as clear cut. In our opinion, businesses that have significant competitive advantages and have strong pricing powers will likely benefit the most. Such businesses will either be able to retain much of the tax benefits such that their returns on capital increase or will be able to use the incremental cash flows to increase investments in their growth projects.

On the other hand, businesses that lack competitive advantages and operate in commodity like industries will see much of the benefit of tax cuts passed down to their customers. An important point to note is that such trickle down of tax cuts is a slow affair and will happen over time driven by competitive pressures. In the interim, earnings of profitable and tax-paying corporates will likely see an improvement.

Ignoring evidence

What is interesting about all of this is that even in the face of ample evidence of poor forecasting ability, analysts, economists, and market participants go on happily participating in their favorite financial sporting event; forecasting. Indeed, it is such a hardwired tendency that in a meeting with a colleague of ours, I was encouraged to take pride in an ability to predict. A rather surprising suggestion given that we take pride in “not” forecasting.

Economic costs and resultant malinvestments

It is important to understand that our poor ability of forecasting and then staying ignorant of that shortcoming has real economic implications. Frequently, corporate finance departments base their cash flow projections on these forecasts driving capital allocation decisions. Investors and entrepreneurs use these forecasts in their investment and capital allocation actions. It is not surprising then that reliance on such forecasts, in capital allocation decision making frameworks, frequently results in malinvestments.

As an example, let’s look at a toll road business in the US, the Indiana Toll Road. In 2006, the ITR Concession Co. acquired a 75-year concession for the Indiana Toll Road, in a transaction valued at US$3.8 billion. At the time of the transaction, Wilbur Smith Associates, a Transportation and Infrastructure consulting firm, predicted that traffic on the toll road will increase by 22% over the first seven years. Instead, traffic volumes shrank by 11% in the first eight years. ITR declared bankruptcy in 2014.

There are no shortages of similar examples of poor forecasts and the resultant capital destruction in India as well. One only needs to look at the balance sheets of Indian PSU banks and NBFCs to realize the extent of malinvestments that result from reliance on such advice.

Our approach to predictions

We have a two-pronged approach towards predictions. Firstly, we actively avoid predictions. Successful investing does not require one to be great at forecasting. Instead, we focus our attention on understanding what is, businesses that have durable competitive advantages and are well positioned to survive through varying economic environments, and the expected returns of such investment opportunities. Secondly, we spend our energies on worrying about potential investment risks and ensuring that our portfolios can live through the thousand-year flood.

As Warren Buffett said, if you can’t predict what tomorrow will bring, you must be prepared for whatever it does. At India Moats Fund, that is the approach we take.

About the Author

Baijnath Ramraika, CFA, is a cofounder and the CEO & CIO of Multi-Act Equiglobe (MAEG) Limited and is the Executive Director at Sapphire Capital. As a portfolio manager, he manages the Global Moats Fund and the India Moats Fund. Contact him at [email protected]. Baijnath’s thoughts and ideas can be read at his blog at www.symantaka.com

Prashant K. Trivedi, CFA, is a cofounder of MAEG and the founder and chairman of Multi-Act Trade and Investments Pvt. Ltd.

MAEG is an investment manager and manages the Global Moats Fund, an investment fund that invests in a global portfolio of high-quality businesses with sustainable competitive advantages. Sapphire manages the India Moats Fund, an investment fund that invests in a portfolio of high-quality Indian businesses with sustainable competitive advantages.

Multi-Act is a financial services provider operating an investment advisory business and an independent equity research services business based in Mumbai, India.

[1] Economic consensus represented by averages published in a report called Consensus Forecasts. [2] https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2019-03-28/economists-are-actually-terrible-at-forecasting-recessions [3] https://www.business-standard.com/article/economy-policy/rbi-sharply-cuts-fy20-gdp-growth-forecast-to-6-1-amid-economic-slowdown-119100401487_1.html