Vltava Fund letter to investors for the second quarter ended June 30, 2019, titled, “Recessions.”

“Economic growth has been going on rather too long already. Wouldn’t it be better to sell all the stocks now, just before the coming recession, wait until it passes, and then buy them back a good bit cheaper?”

Although this idea seems both logical and current, it is in fact a quote from 2012. We heard the very same thoughts in 2013, 2014, 2015, 2016, 2017, 2018, and we are hearing them today. It would have been nice if life and investing were so simple. Reality, however, is a bit more complicated. To be specific, the aforementioned notion has three defects: an incorrect impression of historical economic development, belief in an ability to predict future economic growth, and a distorted impression that stock prices somehow respond predictably to economic growth. I would like to dwell further on each of these three points.

Q2 hedge fund letters, conference, scoops etc

Historic economic growth

A very common thought process today runs as follows: “Since the Great Financial Crisis of 2008, we have experienced uninterrupted economic growth. It has been going on more than 10 years already, which is historically quite long, and it is therefore practically inevitable that the next recession is just around the corner, if it is not in fact upon us already.”

But have we really experienced more than 10 years of economic growth? Looking back, we can see that in the past decade EU was in recession during 2012, Japan had negative economic growth in 2011, and our country did in 2012–2013. Looking around at developing markets, we find that Russia was in a deep depression in 2015 and Brazil in an even deeper one during 2016. The inhabitants and entrepreneurs in these parts of the world surely do not believe that they have lived in a period of long-enduring unbroken economic expansion.

Although the US economy technically has avoided recession since 2008, it has entire sectors (such as manufacturing and energy) that were substantially in recession during 2015 and 2016, and the profits of companies in the S&P 500 index decreased by almost 20% during that time. From an investment perspective, it was a rather considerable recession. It is worth noting that while the profits of US companies decreased in 2015 by 15%, the profits of Japanese companies increased by the same percentage. World economies and the individual stock markets cannot be lumped together.

Future economic growth

If we would take a look at historical economic data (and let us put aside the question of just how precisely we can actually measure such variables as GDP and inflation), our interpretations may differ substantially. This probably would be merely an academic discussion in any case. In practical terms, the future is much more important for investors. Is it in fact possible to reliably predict economic development with reasonable probability? History teaches us that it is not. Still, a lot of investors attempt to do so.

If the US economy has been growing uninterruptedly for 10 years, is there something to exclude the possibility that it would continue growing uninterruptedly for another 10 years? No. Is there something that would exclude its being in a recession at the end of this summer? No. Can we say which of these possibilities is more probable? No. If the economy of EU states has been growing for the past 10 years at the slowest rate in history, does this mean that its growth will accelerate in the next 10 years? Or will it slow down even more? Will the UK economy grow more quickly or more slowly after Brexit than it did within the EU? Can a reliable prediction be made concerning the future growth of the Japanese economy? Do we know how rapidly the Chinese economy is growing, or even how fast it was growing in the past? Is Italy currently in recession or not? What does the case of Australia, which had its most recent recession 30 years ago, tell us about the theory of economic cycles? There is only one honest answer to all these questions – I do not know.

In 1993, when I swooped into the equity markets as a young (which I basically still am, although that is becoming more difficult to recognise) and inexperienced investor, the debate over economic growth and efforts to predict it were identical to those of today.

Over the course of those 26 years I gradually came to two conclusions:

First, through that entire time I have not discovered anyone who could predict economic growth. I doubt there will ever be someone who can. It is not enough to make a prediction that by happenstance corresponds to the actual development once in 15 years. I am speaking here of reliably, systematically, and with high probability making correct predictions again and again. I think this is not possible.

Second, even though historic evidence does not favour them, some investors will always endeavour to manage their portfolios following their own (or second-hand) predictions about the economy’s future development.

Economic growth and stock prices

There exists yet another slight complication to all that was said above. Even if we did know what would be the economy’s development with 100% certainty for, let us say, the next three years, we nevertheless would be unable to say practically anything about the development of stock prices over that same period.

Sometimes, a person’s firm conviction about how the world works prevents one from forming a picture about the way the world actually works. We can take as an example the relatively widespread opinion that there is some direct relationship between economic growth and movements of stock prices. Unfortunately, this is not the case. Another look into history shows that stock prices can both rise and fall during periods of economic growth. They also may increase and decrease during recessions. And if, for example, recession does cause stock prices to decrease, the time shift between these two phenomena may be so great that when the economy can be seen sliding into recession, stock prices may already long ago have recovered.

Predicting the economy’s development is therefore not sufficient for an investor to be successful with his or her predictions. Such an investor also would have to recognise how the various expectations are themselves affecting prices and how investors as a whole will respond to further development. I think that to attempt something like that is a complete waste of time and probably also of money.

What can be done?

Does that mean, therefore, that an investor is completely at the mercy of the goings-on in the markets, or is there some way he or she can successfully withstand recessions? I believe there is in fact plenty that one can do. I will undertake to explain our approach here.

Our first principle is that we do not attempt to manage our investments in accordance with any predictions – be they our own or those of others – concerning the economy’s development or try to predict in which direction stock prices will move in the nearest term. This is something we keep saying over and over again, and I am sure none of you will be surprised. Our second principle is based on the fact that we endeavour to choose only companies that are resistant to recessions. By resistant to recession, I do not mean that a company’s stock price cannot go down, be it during a recession or at any other time. A company I regard as resistant to recession is one whose business will not suffer so much in a recession as to have a substantial impact on that company’s value, its financial situation, and its market position.

History teaches us that the most vulnerable companies in a recession are those that operate with large debt loads, those that rely upon the market to be able to finance themselves, and those whose business models only work when times are very good. Investors often talk about the danger of using financial leverage in a portfolio, but sometimes they forget there exists yet another type of financial leverage (debt) on the level of individual companies. In some cases, it can be deadly. This is why we avoid companies with such characteristics. The companies we hold are all highly profitable, generate strong cash flows, need not rely on the market for financing, and in some cases hold a lot of net cash. If there came a recession as dramatic as the one in 2008, and if it were accompanied by the same credit crisis during which most companies lost their access to financial markets, the companies we own not only would survive but probably would prosper quite well. (By the way, the average age of the companies in our portfolio is 92 years. I believe this confirms their ability to adapt successfully to life’s changes.)

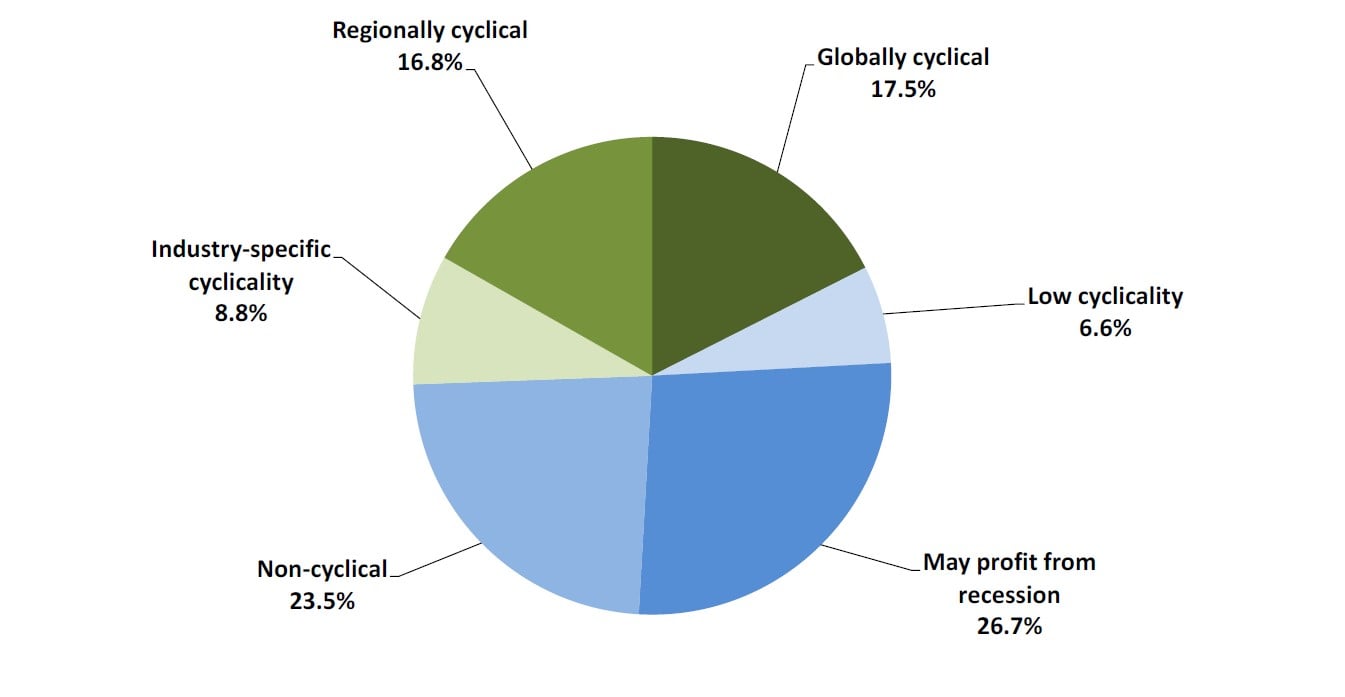

Diversification is another line of defence against recession. When recession strikes an economy, not all companies are affected to the same extent, and its influence may not always even be negative. From this perspective, we can divide our portfolio into six groups. The first group comprises companies which can be considered globally cyclical, for example BMW. This is a global business with cyclical characteristics. Even such a global business is more influenced by regional cycles, however. Three main automotive markets – the Chinese, European, and US markets – are crucial for BMW’s sales and profits. Each of these markets is currently in a different phase of its cycle.

Another group consists of companies which are almost exclusively regionally cyclical. An example is Sberbank. Banking is a partially cyclical sector, although in Sberbank’s case it mainly concerns the economic cycle in the country where the Bank has the overwhelming majority of its activities, and that means Russia. The development of Russia’s economy need not necessarily be correlated with that of the global economy. The Russian economy may at any given point in time be in an entirely different phase of the economic cycle than are those of the world’s major regions.

The third group comprises companies which are cyclical but whose cycle is specific to the industry within which they operate. An example is Samsung, which currently finds itself in the midst of an industry-specific recession. There also are companies whose businesses are less cyclical and only partially related to development within the overall economy. In our portfolio this may be represented by Alimentation Couche-Tard. Certain companies may also be called noncyclical (e.g. LabCorp), and there may even be cases when companies can profit from recessions. For example, Berkshire Hathaway’s fundamental value was positively influenced by the company’s transactions during the crisis year of 2008.

Expressed graphically, the distribution of our portfolio breaks out as follows:

Recession is a scary word for many investors. What it actually entails, however, may vary. It may bring a global recession, as it did 11 years ago. It may bring regional recession, as has occurred several times over the past 10 years. It may bring industry recessions, which are so common that we practically are experiencing at least one at any given time. The relationships between all these economic phenomena, the profits attained by the companies we own, and the movements of their stock prices, are unambiguously not linear.

We have experienced many recessions, and we certainly will see still many more. We accept them as a common part of investing life and even believe that occasional recessions are desirable and beneficial for the economy and for investors. Looking back to the period since the Great Financial Crisis of 2008, stock markets have been doing relatively well even though there have been several regional recessions and a number of dramatic industry recessions. Global equity, as measured by the MSCI World Index, + 145%. The US market as measured by the S&P 500 +225%. Europe as measured by the Stoxx Europe 600 +94%. Japan as measured by the Nikkei 225 +140%. Vltava Fund +333%.

It is interesting that even after these substantial increases most markets are priced reasonably.

Changes in the portfolio

We sold two stocks: Total Produce and AutoNation.

Total Produce was the oldest position in our portfolio. We had started buying it in the spring of 2009 in a price range of EUR 0.32–0.34. We believed it to be an inconspicuous but well-run business whose fundamental value was substantially greater than its share price. More than three years later, in the summer of 2012, the price per share still stood at almost the same level, even though the company’s value had increased in the meantime. An impatient investor would perhaps have thrown in the towel and declared that the market probably recognises the company’s value better than he or she can. It does not, however, seem unusual for us to wait for three years until the market begins to reflect a company’s value in its share price.

Frequently, several years of waiting are rewarded with a very substantial and rapid leap upward. That was also the case for Total Produce. In 2017, the price per share was 2.50. This is, together with the dividends we received for the time we held the stock, more than eight times higher, and our return exceeded 700%.

In that time, we substantially reduced our position. There were two reasons. First, the share price had grown to exceed its value. Second, Total Produce bought half of Dole. We did not like this acquisition, and for two reasons. Total Produce’s debt increased substantially even as Dole itself is substantially indebted. In addition, this changes the character of Total Produce’s business. A company with relatively low fixed capital demands became one with very high fixed capital demands. That combination was a red flag for us. We had thought that Total Produce would be the first stock to earn us a tenfold gain. In the end, we came up a little bit short of that, so this distinction will have to be earned by another company within our portfolio.

In the case of AutoNation, we wanted to reduce our exposure to the automotive sector. Moreover, we had more attractive opportunities available.

Price and value

The fundamental value of our portfolio has not changed much since the beginning of this year. It has been rather stationary. The largest positive influences on the portfolio’s fundamental value came from increase in the fundamental values of Sberbank, Credit Acceptance, Berskhire Hathaway, and also from our only short position, Tesla. The largest negative influence was from decrease in the fundamental values of Samsung and BMW. This year, the prices of our stocks are developing much better than are their fundamental values. The difference between the prices and the portfolio’s fundamental value has narrowed, as per our expectations, but it still remains greater than average.

Daniel Gladis, July 2019

This article first appeared on ValueWalk Premium